Sleep, physical activity, and nutrition are foundational, modifiable behaviors that shape both how long people live (lifespan) and how long they live free of major chronic disease (healthspan).1,2 Yet these behaviors are often studied and targeted one at a time.3,4 Here we share a prospective cohort study of 59,078 UK Biobank participants, which examined how combined improvements across these three domains-collectively termed SPAN (Sleep, Physical Activity, and Nutrition)-relate to gains in lifespan and healthspan using device-measured sleep and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), alongside a validated diet quality score (DQS).5 Over a median follow-up of 8.1 years, the study estimated life expectancy and disease-free life expectancy across joint SPAN categories and a composite SPAN score. The findings suggest that while large changes in any single behavior may be required to achieve meaningful benefits, small concurrent improvements across all three can be associated with substantial gains, including an estimated ~1 extra year of lifespan from as little as +5 minutes/day sleep, +1.9 minutes/day MVPA, and +5 DQS points. More sizable combined changes were associated with several additional years of healthspan.5 These results support a pragmatic public health message: modest, multi-behavior "micro-changes" may be more feasible-and still meaningful-than major changes in one domain alone.

Sleep, physical activity, and diet are tightly interdependent in real life. Poor sleep can dysregulate appetite and energy balance, potentially increasing caloric intake; it can also reduce energy and motivation for movement. Diet composition can influence sleep quality, and physical activity can improve sleep timing and depth. The study positions SPAN as a system of interacting behaviors rather than three isolated exposures, arguing that a single-behavior research and policy mindset may miss synergistic effects and undervalue small, coordinated improvements.6

This matters because many countries have seen lifespan rise while healthspan stagnates or declines¡Xmeaning more years lived with chronic conditions.1,2 From a prevention standpoint, delaying onset of major diseases such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), cancer, type 2 diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and dementia is central to improving quality of life and reducing healthcare burden.7 The study therefore focused on both all-cause mortality (lifespan) and disease-free life expectancy (healthspan) across those five conditions.5

Cohort and Measurements5,8

The analysis used 59,078 adults from the UK Biobank accelerometry sub-study (recruited 2006-2010; median age ~64 years). Between 2013 and 2015, participants wore a wrist accelerometer for 7 days, enabling device-based estimates of:

Outcomes and Follow-up5,6,9

Over a median follow-up of 8.1 years, the cohort accumulated: 2458 deaths, 9996 CVD, 7681 cancers, 2971 type 2 diabetes, 1540 COPD, and 508 dementia events. Lifespan and healthspan were estimated using life-table methods and hazard ratio-adjusted rates from multivariable models.

The researchers grouped each SPAN behavior into tertiles and evaluated 27 combinations (3 sleep X MVPA X 3 DQS). They also created a composite SPAN score (0-100) to quantify incremental "dose" changes needed for specific gains.

The tertile ranges were practical and interpretable:

Notably, the "medium MVPA" range begins just above ~22 minutes/day, aligning closely with common guideline-equivalent thresholds.

Compared with the least favorable tertiles, the most favorable SPAN pattern (notably high MVPA, moderate sleep, and high DQS) was associated with:

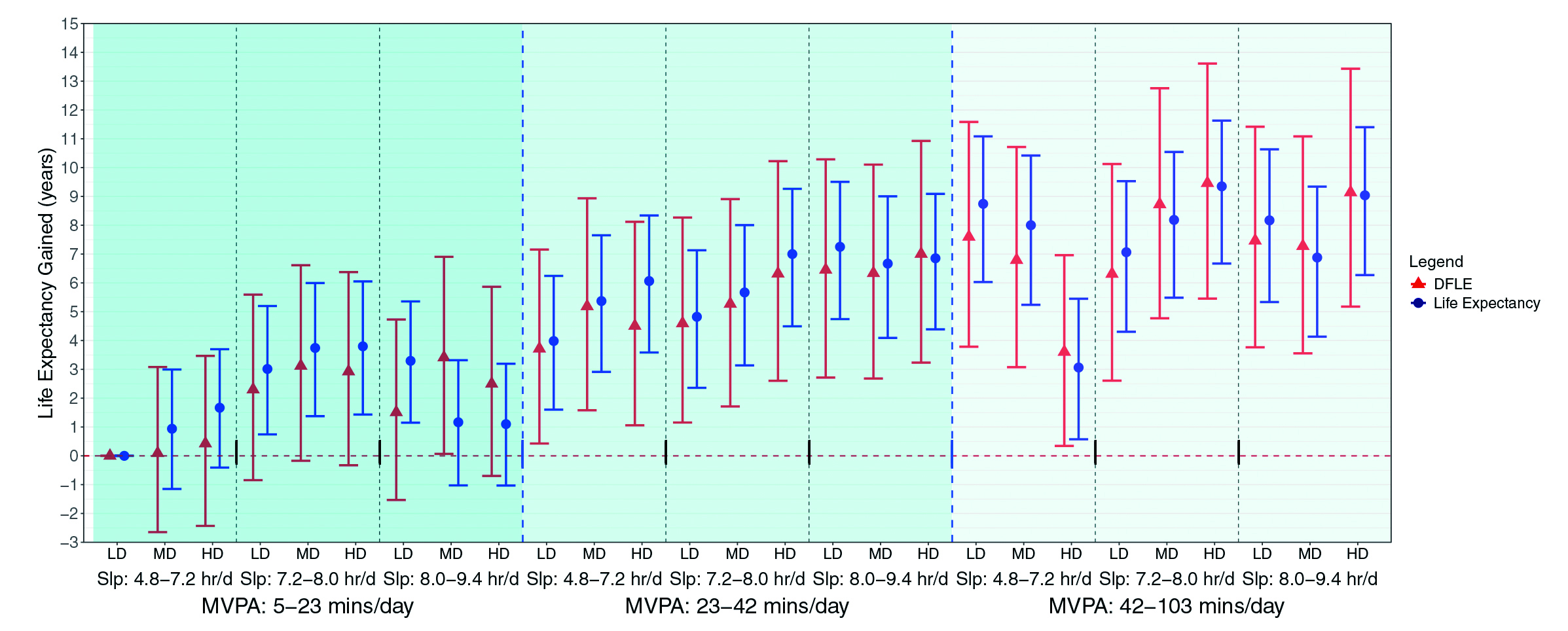

This is a striking finding: the model-based estimates suggest that optimal combined behaviors correspond to nearly a decade more life and a decade more life free of major chronic disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Multivariable-adjusted lifespan and healthspan associated with joint sleep, physical activity, and nutrition exposures.5 DFLE, Disease-Free Life Expectancy; HD, High Diet Quality; LD, Low Diet Quality; MD, Medium Diet Quality; Slp, Sleep

Across joint categories, moving into the moderate MVPA group (>22 min/day) was a visible "turning point" for gains, even when sleep and diet were not optimal. For example, moderate MVPA + moderate sleep + high DQS corresponded to about +7.00 years lifespan and +6.32 years healthspan relative to the lowest tertiles.

A central contribution of the study is translating statistical associations into minimum combined ¡§doses¡¨ of change required for meaningful gains. Compared with the 5th percentile baseline for all three behaviors, the study estimated that ~1 additional year of lifespan was associated with +5 minutes/day sleep, +1.9 minutes/day MVPA, and +5 points in DQS (examples given: ~½ serving of vegetables/day or ~1.5 servings of whole grains/day). The practical message is powerful: for lifespan, small shifts across multiple behaviors may add up.

Healthspan required larger changes before estimates became statistically clear. The study reported that ~4 additional years of healthspan were associated with +24 minutes/day sleep, +3.7 minutes/day MVPA, and +23 DQS points (example pattern: +1 cup vegetables/day, +1 serving whole grains/day, and +2 servings fish/week). In other words, preventing or delaying major chronic disease onset (not just mortality) appears to demand more substantial combined improvements.

The researchers tested whether the combined effect of SPAN exceeds what you would expect from simply adding the parts (interaction on an additive scale). They found:

This nuance matters: even if synergy is limited for disease-free life expectancy, the combined approach still lowered the "required dose" of change relative to pursuing one behavior alone.

While the study does not prescribe an intervention, it implies a pragmatic approach:

Of note, due to selection bias, residual confounding, and its observational design, the study cannot establish causality and has limited generalizability.

This population cohort study provides an unusually actionable translation of lifestyle epidemiology: it estimates how small, combined changes in sleep, physical activity, and diet quality relate to gains in both lifespan and healthspan. The standout message is that the ¡§minimum effective change¡¨ may be far smaller when behaviors improve together: roughly +5 minutes/day sleep, +2 minutes/day MVPA, and a +5-point diet quality improvement were associated with ~1 extra year of lifespan. More substantial combined improvements were associated with multiple additional years free of major chronic disease. Although observational and model-based, the results support a practical public health direction: instead of demanding major transformation in one domain, health authorities could encourage achievable micro-changes across the SPAN triad, potentially leveraging behavioral interdependence to enhance adherence and population impact.

References

1. Ng R, et al. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;49:113¡V30. 2. Garmany A and Terzic A. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2450241. 3. Chaput J-P, et al. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2023;19:82¡V97. 4. Godos J, et al. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;57:101430. 5. Koemel NA, et al. eClinicalMedicine. 2026 January 13: 103741. Online first. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2025.103741. 6. Stamatakis E, et al. BMC Med. 2025;23:111. 7. Landeiro F, et al. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024;5:e514¡Ve523. 8. Doherty A, et al. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0169649 9. Chudasama YV, et al. BMC Med. 2019;17:108.