Current Perspectives in Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is an increasingly common sleep-dependent breathing disorder. However, most OSA patients are undiagnosed and untreated. Untreated OSA is associated with not only reduced quality of life, lost work productivity and increased workplace and motor vehicle accidents resulting in injury and fatality, but also long-term health consequences such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders, cognitive impairment and depression1,2. With effective management, daytime sleepiness, fatigue, quality of life and blood pressure can all be improved2.

Epidemiology and Clinical Presentation of OSA

OSA is a breathing disorder characterised by episodic sleep state-dependent collapse of the upper airway, resulting in periodic reductions (hypopnea) or cessations (apnea) of airflow despite respiratory effort, with consequent hypoxia, hypercapnia, or arousals from sleep. The presence and severity of OSA are typically defined by the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), the number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep. The presence of OSA is defined as an AHI of 5 or more events per hour2,3.

OSA is highly prevalent in the general population, and occurs at all ages4. The most common symptom of OSA is excessive daytime sleepiness, which has been reported in up to 90% of patients2. Other common symptoms include fatigue, frequent nocturnal waking due to choking or gasping, nocturia, morning headaches, poor concentration, irritability, memory loss, and erectile dysfunction1,5. However, many OSA patients are asymptomatic2.

Pathophysiology of OSA

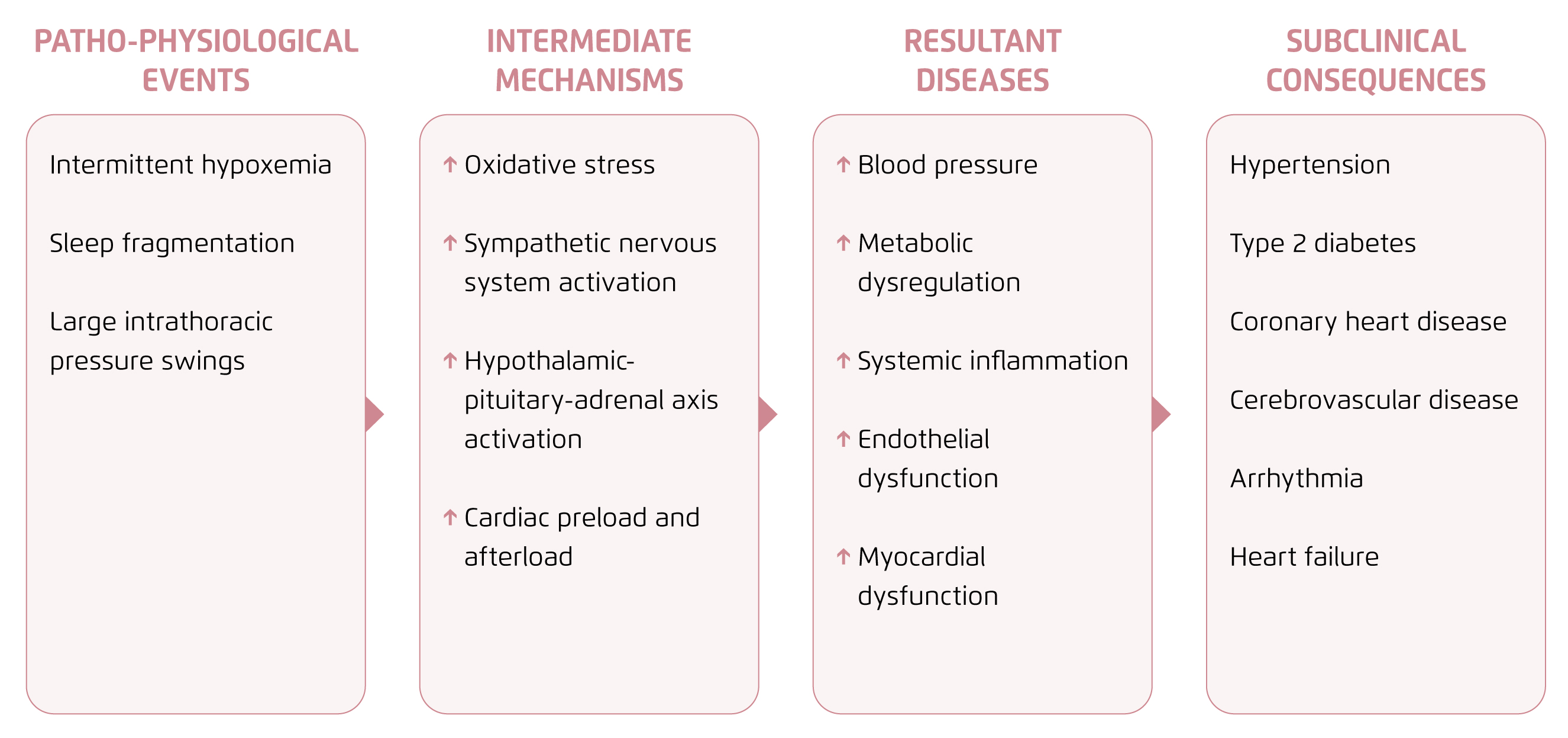

As OSA is a major cause of excessive sleepiness, it contributes to reduced quality of life, impaired work performance, and increased risks of motor vehicle crash and occupational injury2,5. Since several pathophysiologic mechanisms are upregulated in OSA, including oxidative stress, sympathetic nervous system activity, hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis activity, and cardiac preload and afterload, OSA is associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease including hypertension, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, arrhythmia and heart failure, as well as metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (Figure 1)2.

Figure 1. OSA could be a contributor to various cardiovascular and metabolic diseases2

Risk factors for OSA are conditions that reduce the size of the resting pharynx or increase airway collapsibility3. Obesity, central body fat distribution, and large neck girth are well-established risk factors6. Male sex is another important risk factor. Higher androgen levels may increase muscle mass in the tongue and worsen obstructive sleep apnea, while progesterone stimulation of upper-airway muscles and ventilation may contribute to the lower prevalence of OSA among premenopausal women than among older women3. Additional risk factors for OSA include older age, increased tonsillar and adenoid tissue and certain craniofacial abnormalities (retrognathia and maxillary insufficiency), and nighttime nasal congestion3,6.

Management of OSA

Various treatment modalities are available for OSA, comprising medical devices, surgical procedures and behavioural interventions2,6.

Medical devices

Positive airway pressure (PAP), including continuous PAP (CPAP), is the frontline therapy for all patients with symptomatic OSA of any severity. PAP is applied with a tight seal to the nose or mouth (or both). It acts as a splint to prevent airway collapse during inspiration while CPAP provides a constant level of positive pressure across inspiration and expiration. Although PAP is highly effective in normalising the AHI, benefit depends on adequate adherence to therapy, which is commonly defined as use for at least 4 hours per night for at least 5 nights per week2,3. However, approximately 65% to 80% of patients who start PAP therapy continue using it after 4 years. To improve PAP adherence, education about risks of OSA and the expected benefits of PAP therapy, monitoring of PAP use with reinforcement and support for technical problems, cognitive behavioural therapy and motivational enhancement therapy are needed. Also, automatic titrating PAP devices, which monitor airflow and adjust pressure in response to changes in flow, have facilitated initiation of PAP therapy. In conditions characterised by hypoventilation, bilevel PAP devices, which deliver a higher pressure during inspiration than during expiration, may be useful2.

Patients with mild-to-moderate OSA who are unable to or prefer not to use PAP therapy may be candidates for oral appliances (mandibular repositioning devices)2,3. These devices consist of plates made to fit the upper and lower teeth, and provide adjustable forward advancement of the mandible relative to the maxilla during sleep, leading to increased upper airway volume and reduced airway collapsibility2. In a randomised controlled trial, CPAP was shown to be more effective than an oral appliance in reducing the AHI, but adherence was greater with the oral appliance3.

Surgical procedures

In the recent years, surgical options have expanded for OSA, and ideal candidates for these surgical procedures are nonobese persons with abnormalities in craniofacial pharyngeal structures3. The most common surgical procedures for managing OSA modify upper airway soft tissues such as palate, tongue base, and lateral pharyngeal walls, and the most extensively studied procedure is uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, which involves resection of the uvula and part of the soft palate. To manage OSA, the bony structures of the face can also be modified. The best-studied procedure is maxillomandibular advancement, in which the upper airway is enlarged via LeFort I maxillary and bilateral mandibular osteotomies with forward fixation of the facial skeleton by approximately 10 mm. A newer surgical procedure is hypoglossal nerve stimulation, which involves surgically implantation of an electrode on the medial branch of the hypoglossal nerve to enhance tongue protrusion and stabilise the upper airway during inspiration2.

Behavioural interventions

Weight loss should be recommended to all overweight or obese patients with OSA, including those using PAP and those who are asymptomatic, or whose symptoms are minimally bothersome and pose no apparent risk to driving safety. Weight loss can be achieved via lifestyle interventions, medication or bariatric surgery. No matter how it is achieved, it is effective for managing OSA. In addition, weight loss can have positive effects on many cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Apart from weight loss, regular aerobic exercise, behavioural interventions such as avoiding supine sleep position or maintaining side sleep position with the help of positioning pillows or devices (positional therapy), and avoiding medications and substances that promote relaxation of the upper airway, including alcohol, benzodiazepines and narcotics, can be beneficial for OSA patients2,3.

References

1. Osman AM, et al. Nat Sci Sleep 2018;10:21-34. 2. Gottlieb DJ and Punjabi NM. JAMA 2020;323:1389-1400. 3. Veasey SC and Rosen IM. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1442-1449. 4. Bonsignore MR, et al. Multidiscip Respir Med 2019;14:8. 5. Laratta CR, et al. CMAJ 2017;189:E1481-E1488. 6. Salman LA, et al. Curr Cardiol Rep 2020;22:6.