Facing Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder during a Pandemic

Reminders of personal hygiene practice have been on the rise since the COVID-19 pandemic is sweeping across the world in the past months. Hand washing, household cleaning, social distancing and so on — hygiene and protection become the centre of concern for every person. The developing and ever-changing situations, not to mention an overflow of information have created fear and uncertainty in our everyday lives. Meanwhile, the potential impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health has also opened up an aspect besides cautions on physical health. With the heightened concerns over hygiene and infection avoidance, would the outbreak pose a challenge to patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)? How would these patients cope with the outbreak?

OCD: An Overview

The Diagnostic and Statistical Mental Disorders Manual (DSM-5) classifies a heterogeneous collection of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. It is characterised by the presence of obsessions and/or compulsions. As a broad definition, obsessions are represented as recurrent and persistent thoughts, urges or images that are experienced as intrusive and unwanted. Compulsions are defined as repetitive behaviours or mental acts that an individual feels driven to perform in response to an obsession, in order to reduce the distress arose from obsessions or to prevent a fear event (e.g. catching an illness). To justify a clinical diagnosis of OCD, obsessions and compulsions must be time-consuming, and would cause clinically significant distress or impairment in various areas of functioning1.

A sizable epidemiological study found the current (12-month) and lifetime prevalence of OCD at around 1% and 2.3% respectively2. According to a local survey released in 2013, all phobias and OCD collectively accounted for 1.5% in the population3. Adverse childhood events and behavioural factors may contribute to the future development of different obsessive/compulsive symptom dimensions4. Onset of OCD at earlier ages is associated with a longer duration of illness and negatively predicted long-term clinical outcomes5. While about 20% to 30% of OCD patients managed to improve their symptoms significantly, 40% to 50% of patients displayed moderate improvement; the remaining 20% to 40% either stayed unimproved or experienced a worsening of symptoms6.

Apart from quality of life (QoL) and functional impairment7 as well as chances in developing other comorbid mental health disorders2, severe cases of OCD may also complicate with physical morbidity due to compulsive rituals. For instance, dehydration can be a consequence of neglecting the need of drinking water in a way to reduce frequent toilet visits so as to avoid getting contaminated8. Also, comorbidity with general medical conditions are common in OCD patients, such as endocrine/metabolic diseases (25.9%), gastrointestinal (20.5%) and cardiovascular diseases (13.6%)9.

Contamination Thoughts and Acts

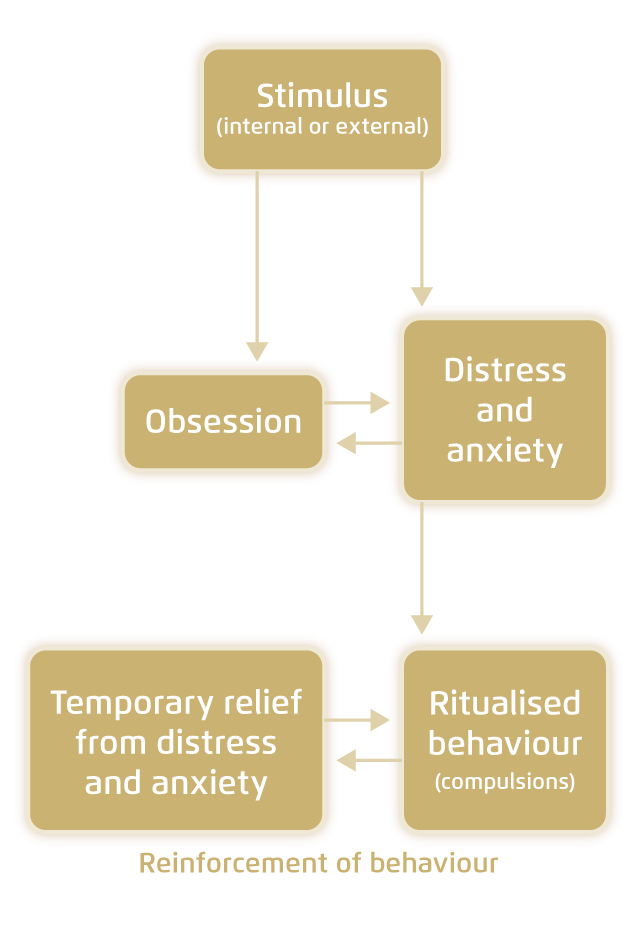

Among the clinically-characterised symptom dimensions, contamination fear is one of the most common form of OCD which accounts for 55% to 65% in patient-reported concerns2,10. When facing infection and contamination risks, patients with OCD may make overreacting judgements which can generate washing and cleaning compulsions10. These translate into hygiene-related behaviours even without physical contact. Patients with OCD showing mental contamination concerns reported frequent handwashing and spending longer periods of time washing and cleaning daily11,12. The recurrent and persistent fear of contamination can lead to a cycle of obsessional thoughts and acts (Figure 1)13.

Figure 1. Theoretical basis of obsessive-compulsive behaviour13

The increasing fear of infection and worries about social distancing in current outbreak may be particularly challenging for patients with OCD. The feeling of guilt and disgust has a crucial role in the causes and maintenance of OCD14. Disgust elicits from an individual’s appraisal towards surrounding objects for their potential of harm. Contamination-based OCD may over-estimate the consequences of touching a “contaminated” object (a dysfunction in appraisal) and result in a “false alarm”. This triggers the individual to perform neutralising behaviours, such as excessive washing, in order to get relieved from the distress10,15.

Anxiety May Make it Worse

In the midst of the outbreak, the American Psychiatric Association reported an online survey that 48% of Americans were anxious about infection with coronavirus, while 59% felt that coronavirus had a serious impact on their daily lives16. A self-reporting survey conducted in China revealed that 35% of over 52,000 respondents experienced peritraumatic psychological distress, after the World Health Organization announced the outbreak as a “public health emergency of international concern” in February 2020. The psychological distress was indicated by measures including frequency of anxiety, avoidance and compulsive behaviour17.

Based on a four-year study on factors contributing to the course of QoL in OCD patients who were in remission, comorbid anxiety and depressive symptoms were correlated to an unfavourable course of QoL in patients with OCD. This gives an implication that patients with OCD should be more attended if anxiety and depressive symptoms are present18.

New Way Out for Therapy Delivery

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) with exposure and response prevention (ERP) have been established as an effective psychotherapy for OCD19. With the concern of social distancing in the wake of an outbreak, there is a need to seek for an alternative mode of health service delivery. A pilot randomised controlled trial suggested that ERP treatments using video conferencing brought about similar outcomes compared to regular face-to-face sessions, as reflected by stable symptom improvement at follow-up20. Through the aid of technology, treatments can be more accessible in distanced situations21.

Advice to Patients

Witnessing the pandemic, people going through mental health disorders may be more vulnerable to the constantly changing situation. Uncertainty and fear can bring about adverse psychological consequences. The American Psychological Association advises limiting the time spent in reading news and updates as a way to help patients with OCD overcome compulsive checking, which in turn reduces excess anxiety and uncertainty in the first place. Patients should be reassured in following the valid hygiene recommendations as directed by authorities. In the meantime, it is important to encourage patients to confront the feelings while keeping their compulsions under control22.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Mental Disorders Manual of Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Vol 17.; 2013. 2. Ruscio AM, Stein DJ, Chiu WT, Kessler RC. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(1):53-63. 3. Lam LCW, Wong CSM, Wang MJ, et al. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(9):1379-1388. 4. Grisham JR, Fullana MA, Mataix-Cols D, et al. Psychol Med. 2011;41(12):2495-2506. 5. Dell’Osso B, Benatti B, Buoli M, et al. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(8):865-871. 6. Levant B. Obsessive Compulsive Disorders. In: Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences. Elsevier; 2014. 7. Huppert JD, Simpson HB, Nissenson KJ, et al. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(1):39-45. 8. Drummond LM, Hameed AK, Ion R. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(2):154. 9. Aguglia A, Signorelli MS, Albert U, Maina G. Psychiatry Investig. 2018;15(3):246-253. 10. Bhikram T, Abi-Jaoude E, Sandor P. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2017;42(5):300-306. 11. Coughtrey AE, Shafran R, Lee M, Rachman SJ. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2012;40(2):163-173. 12. Vickers K, Ein N, Koerner N, et al. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2017;14:71-83. 13. Pauls DL, Abramovitch A, Rauch SL, Geller DA. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(6):410-424. 14. Ottaviani C, Collazzoni A, D’Olimpio F, et al. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2019;20:21-29. 15. Abramowitz JS, Taylor S, McKay D. Lancet. 2009;374(9688):491-499. 16. Canady VA. Ment Heal Wkly. 2020;30(13):5. 17. Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, et al. Gen Psychiatry. 2020;33(2):e100213. 18. Remmerswaal KCP, Batelaan NM, Hoogendoorn AW, et al. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019:1-12. 19. Fenske JN, Schwenk TL. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(3):239-245. 20. Vogel PA, Solem S, Hagen K, et al. Behav Res Ther. 2014;63:162-168. 21. Canady VA. Ment Heal Wkly. 2020;30(12):1-4. 22. American Psychological Association. Managing COVID-19 concerns for people with OCD. http://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19/managing-ocd. Accessed June 2020.