A Review on the Health Impact of Baby-led Weaning

The biggest dietary change in every human¡¦s life is the change from consuming solely breast milk, or infant formula, to consuming complementary (solid) food in order to ensure sufficient nutritional quantity and quality for growth and overall development in its fullest potential1. While the transition period is crucial in determining one¡¦s short- and long-term growth, development and health, it also affects the acquisition of optimal food-related behaviours, skills, and attitudes2. Hence, optimisation for complementary food feeding has been subject to debate. Apart from traditional parent-led weaning by spoon feeding, baby-led weaning (BLW) has been advocated as an alternative approach to introducing solid foods for infants. In order to uncover the controversy on complementary food feeding, established evidence on health benefits and clinical concerns about BLW will be reviewed.

Ready for Weaning Yet?

In prior to the selection on weaning, i.e. the introduction of complementary feeding, the approach and the timing for dietary change have to be considered. If weaning is delayed, the risk of low growth, delayed motor and mental development, neurological and mental fatigue, frequent diarrhoea, and a lack of macro- and micronutrients in infants’ body would be increased3. However, it have been reported that early initiation of weaning at 4-6 months is associated with increased risks of multiple adverse health outcomes including childhood obesity, allergies, childhood respiratory illness, iron deficiency and anaemia4. Thus, weaning should be introduced in a safe, well-timed and adequate manner.

Currently, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months, implementing weaning from 6 months onwards5. However, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) reported that, as long as the texture and nutritional content of foods are appropriate and foods are prepared following good hygiene practices, there is no convincing evidence that early initiation (less and 6 months) of weaning is associated with adverse health effects6. Moreover, the EFSA addressed that the majority of infants need complementary foods from around 6 months of age, whereas infants at risk of iron depletion may benefit from earlier introduction of complementary foods that are a source of iron6.

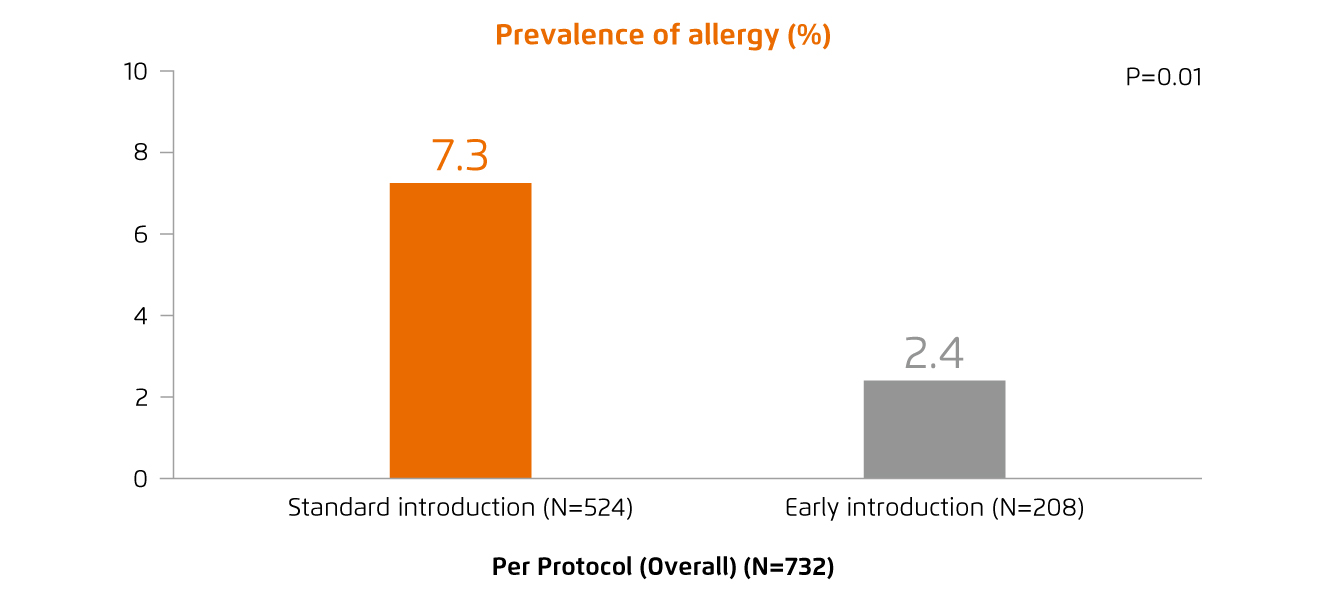

A recent survey by Cook et al (2020) suggested that, practically, a majority of parents in the United Kingdom initiated weaning before 6 months. The decision on the early initiation was influenced by various factors including parents’ intuition regarding infant readiness, traditional cultural practices and familial influences4. Notably, according to the LEAP study (2015)7 and the EAT study (2016)8, early introduction of allergenic foods in breast-fed infants of 3 months of age was safe and was associated with a lower prevalence of any food allergy (Figure 1)8. Hence, solid food of appropriate texture with sufficient nutrient content, even allergenic food, can be considered for infants since 4 to 6 months old.

The Concerns on BLW

Traditionally, parents introduce complementary foods by spoon feeding their infant pureed foods. As the infant learns to consume solid foods, a wider variety of foods with complex textures will be provided9. BLW is an alternative approach to introducing solid foods in which infants feed themselves all their food from the start of complementary feeding. BLW presents the foods eaten by the family so that infants experience the family diet, whereas the food offered is manageable to handle and eating crisp hard vegetables and whole nuts are avoided3. Proposed advantages of BLW include improved infants’ ability to respond appropriately to appetite and satiety cues, leading to an improved body weight and reduced food fussiness.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of allergy to one or more foods in EAT study8

However, concerns have been raised that infants may not eat enough, particularly if self-feeding skills are poor10.

Apart from insufficient energy intake, there are clinical concerns on BLW for increasing the risk of inadequate intake of nutrients, such as iron. In contrast, increased salt intake by infants with BLW has been reported, though there was no difference in salt intake was observed as compared to traditional spoon-feeding infants11. Essentially, as infants may have not developed the oral motor function required to safely ingest whole foods, the risk of choking is noteworthy. Former survey revealed that 30% of infants with BLW had at least one episode of choking with solid food ingestion12.

Evidence on Health Impacts of BLW

In view of the clinical concerns addressed, investigations comparing health outcomes in infants with BLW and those with traditional spoon-feeding have been performed. Morison et al (2016) reported that BLW infants were more likely than spoon-fed infants to have fed themselves all or most of their food when starting complementary feeding. Essentially, the results showed no difference in energy intake and choking risk between BLW and spoon-fed infants. However, the results indicated that BLW infants appeared to have higher intakes of total fat and saturated fat, and lower intakes of iron, zinc and vitamin B1213. Of note, the results in relation to saturated fat intake were not consistent as compared to other studies though increased total fat intake by BLW infants was confirmed14. Additionally, no previous study shows growth faltering in infants with BLW.

While compromised nutrient intakes are concerned in relation to BLW, a randomised control trial by Daniels et al (2018) involving 206 infants demonstrated that BLW does not increase the risk of iron deficiency in infants when their parents are given advice to offer ¡¥high-iron’ foods with each meal. Notably, the study also indicated that infants in spoon-feeding group obtained most of their zinc from vegetables, whereas infants with BLW obtained most of their zinc from breads and cereals15.

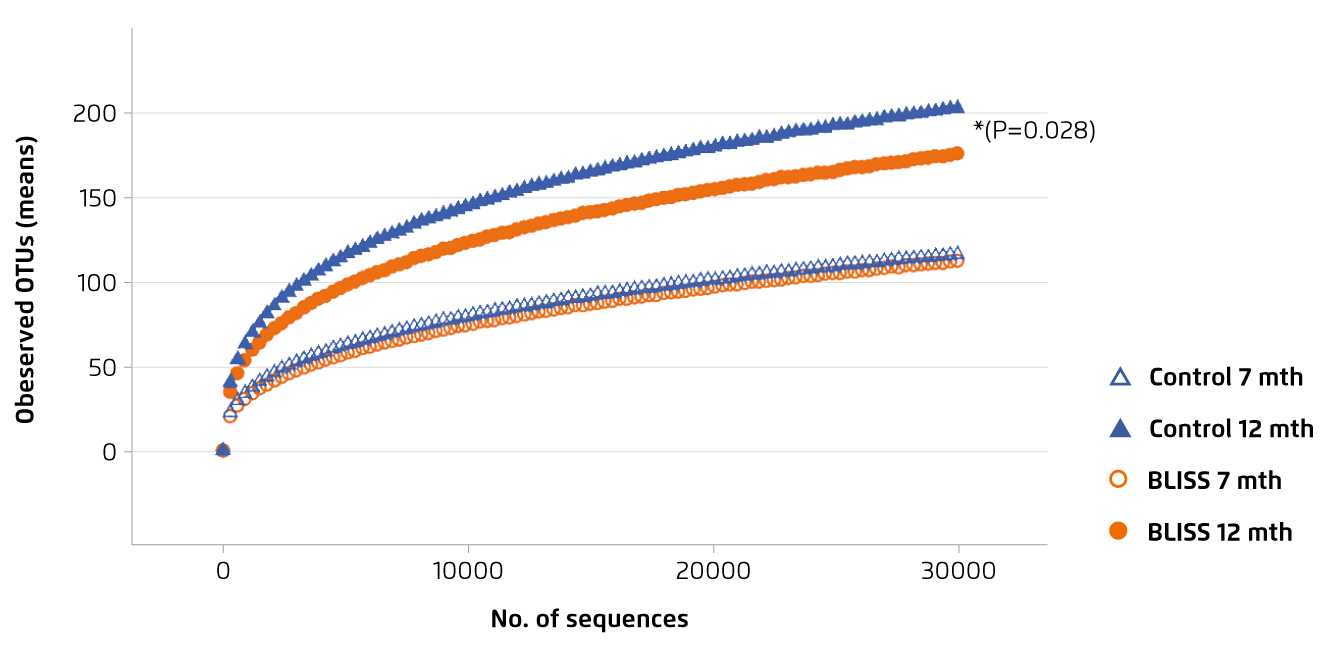

Interestingly, an analysis on faecal microbiotas of infants demonstrated that infants with BLW resulted in a faecal microbiota with a less complex composition than infants following traditional spoon-feeding. Lower intakes of fruit and vegetables and of dietary fibre are partially responsible for this lower alpha diversity, as reflected by the number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs, Figure 2)16. However, the difference in alpha diversity between groups is modest and cannot be related to changes in child development or health.

Practical Tips for BLW

In evaluating the pros and cons of both spoon feeding and baby-led weaning, there is still no solid evidence guiding which feeding approach is preferred though the role of infant feeding has been investigated extensively. Nonetheless, responsive feeding is preferred over regular feeding since responsive feeding allows infants to enjoy eating and encourages them to experience new tastes and textures. Of importance, it also facilitates behavioural change such as asking for help and helps building trust between infants and their caregivers.

While former research works highlighted certain potential risks associated with BLW, clinical information and guidance regarding introduction of complementary foods to parents interested in BLW are essential. In particular, most easily graspable foods, such as fruits and steamed vegetables, which are the most commonly introduced during BLW, are known to be generally low in iron17. Thus, nutrient contents in the food offered to infants need to be aware.

On the other hand, it is inappropriate, during the first year of age, to add salt to food, due to the increased risk of hypertension in later age. Moreover, an excessive consumption of sweetened beverages before 1 year of age would increase caloric intake, which is associated with obesity in childhood. Similarly, excessive protein intake during weaning is correlated with the risk of obesity in later age18. Notably, allergenic foods, such as peanuts, cows’ milk and shellfish, are advised to be carefully introduced into the infant’s diet in small amounts and one at a time19. Last but not least, medical practitioners should closely monitor the infant’s growth regardless of weaning approach.

Figure 2.

Rarefaction curves of observed OTUs16, BLISS=Baby-led introduction to solids

References

1. Gomez MS, Novaes APT, da Silva JP, et al. Rev Paul Pediatr 2020;38:e2018084. 2. Boswell N. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(13):7165. 3. Utami AF, Wanda D, Hayati H, Fowler C. BMC Proc 2020;14:26-8. 4. Cook EJ, Powell FC, Ali N, et al. Matern Child Nutr 2021;17(2):e13108. 5. Brown A, Jones SW, Rowan H. Curr Nutr Rep 2017;6:148. 6. EFSA Panel on Nutrition, et al. EFSA J 2019;17(9):e05780. 7. DuToit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. N Engl J Med 2015;372:803-13. 8. Perkin MR, Logan K, Tseng A, et al. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1733-43. 9. Morison BJ, Heath A-LM, Haszard JJ, et al. Nutrients 2018;10(8):1092. 10. Taylor RW, Williams SM, Fangupo LJ, et al. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171:838-846. 11. Erickson LW, Taylor RW, Haszard JJ, et al. Nutrients 2018;10:740. 12. Townsend E, Pitchford NJ. BMJ Open 2012;2(1):e000298. 13. Morison BJ, Taylor RW, Haszard JJ, et al. BMJ Open 2016;6(5):e010665. 14. Alpers B, Blackwell V, Clegg ME. Public Health Nutr 2019;22:2813-22. 15. Daniels L, Taylor RW, Williams SM, et al. BMJ Open 2018;8(6):e019036. 16. Leong C, Haszard JJ, Lawley B, et al. Appl Environ Microbiol 2018;84(18):e00914-18. 17. D’Auria E, Bergamini M, Staiano A, et al. Ital J Pediatr 2018;44(1):49. 18. Alvisi P, Brusa S, Alboresi S, et al. Ital J Pediatr 2015;41:36. 19. Reeves J. BDJ Team 2018;5:1-4.