Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease with Magnetic Sphincter Augmentation

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common disease globally, with the highest prevalence of 18.1%-27.8% in the North America. The prevalence of GERD is lower in East Asia ranging from 2.5-7.8%. However, the trend is gradually increasing in this region1. GERD adversely impact the quality of life (QoL) of patients and is associated with increased risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma2. Currently, there are various treatment options available for patients with GERD, whereas proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the mainstay in the management of the disease. Unfortunately, unmet needs of medical treatment of GERD, including refractory GERD symptoms and economic burden upon long-term medication use, have been reported3. Hence, anti-reflux surgical procedures have been developed. Notably, the magnetic sphincter augmentation (MSA) has been demonstrated effective in controlling GERD.

Treatment Options for GERD

Clinically, there are 3 major means of treating GERD including lifestyle intervention, medication therapy and surgical treatment. The selection of treatment for GERD varies depending on the progression and symptoms developed. Lifestyle intervention, such as head of bed elevation and avoidance of late-night meals, is an important component in the management of GERD4.

In addition to lifestyle intervention, medication therapy such as PPIs is the mainstay in the management of GERD. Nonetheless, PPIs is reported effective in controlling heartburn in the majority of patients with GERD, but the treatment may not control symptoms such as regurgitation especially in patients with compromised lower oesophageal sphincter (LES) and/or hiatal hernias5,6. Previous opinions suggested that inadequate dosing, nonadherence as well as unresponsiveness to PPIs are associated with the suboptimal efficacy4,7. Moreover, the potential complications of long-term use of PPIs might limit the application of the medication in management of GERD1. This hence highlights the clinical significance of surgical treatment for the disease.

Principle of MSA

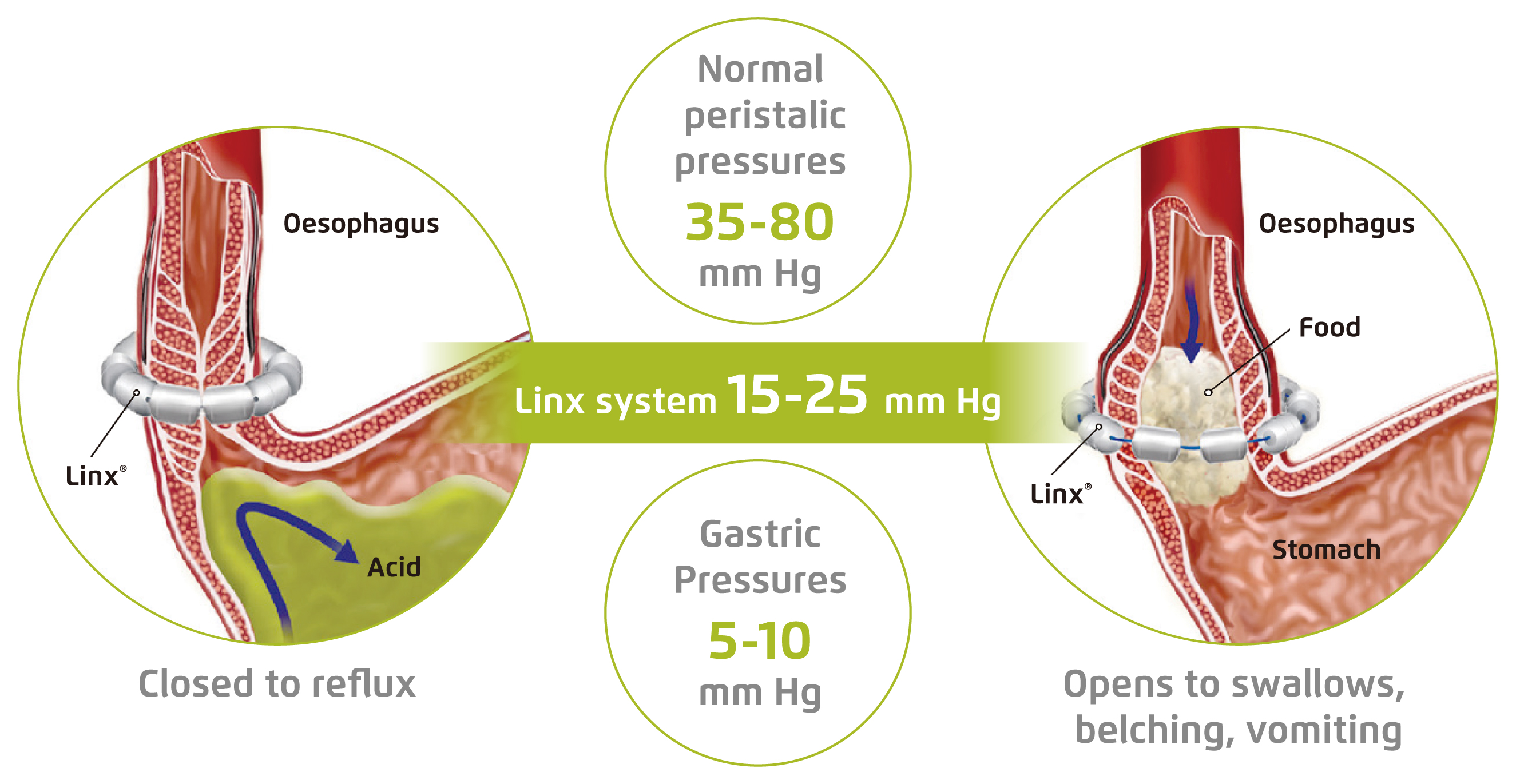

The pathogenesis of GERD is complicated, whereas dysfunction of the oesophagogastric junction (EGJ) is reported to be the main mechanism, especially the LES malfunctions8. The MSA was developed in the mid to late 2000s as an alternative surgical procedure of laparoscopic fundoplication (LF), the gold standard for surgical GERD management. The MSA device consists of a bracelet of biocompatible titanium-encased beads with magnetic cores hermetically sealed inside. The beads are interlinked with independent titanium wires forming an expandable ring placed circumferentially around the oesophagus near EGJ that allows dynamic augmentation of the LES without compression of the oesophagus9. The strength of the magnets of MSA device is calibrated to restore LES function while preserving normal physiological functions. Practically, the magnetic force holds the beads close together to prevent reflux, whereas the beads separate in response to swallowing and then resume to the original configuration (Figure 1)4.

Figure 1. Preventing GERD with MSA system4

Clinical Efficacy of MSA

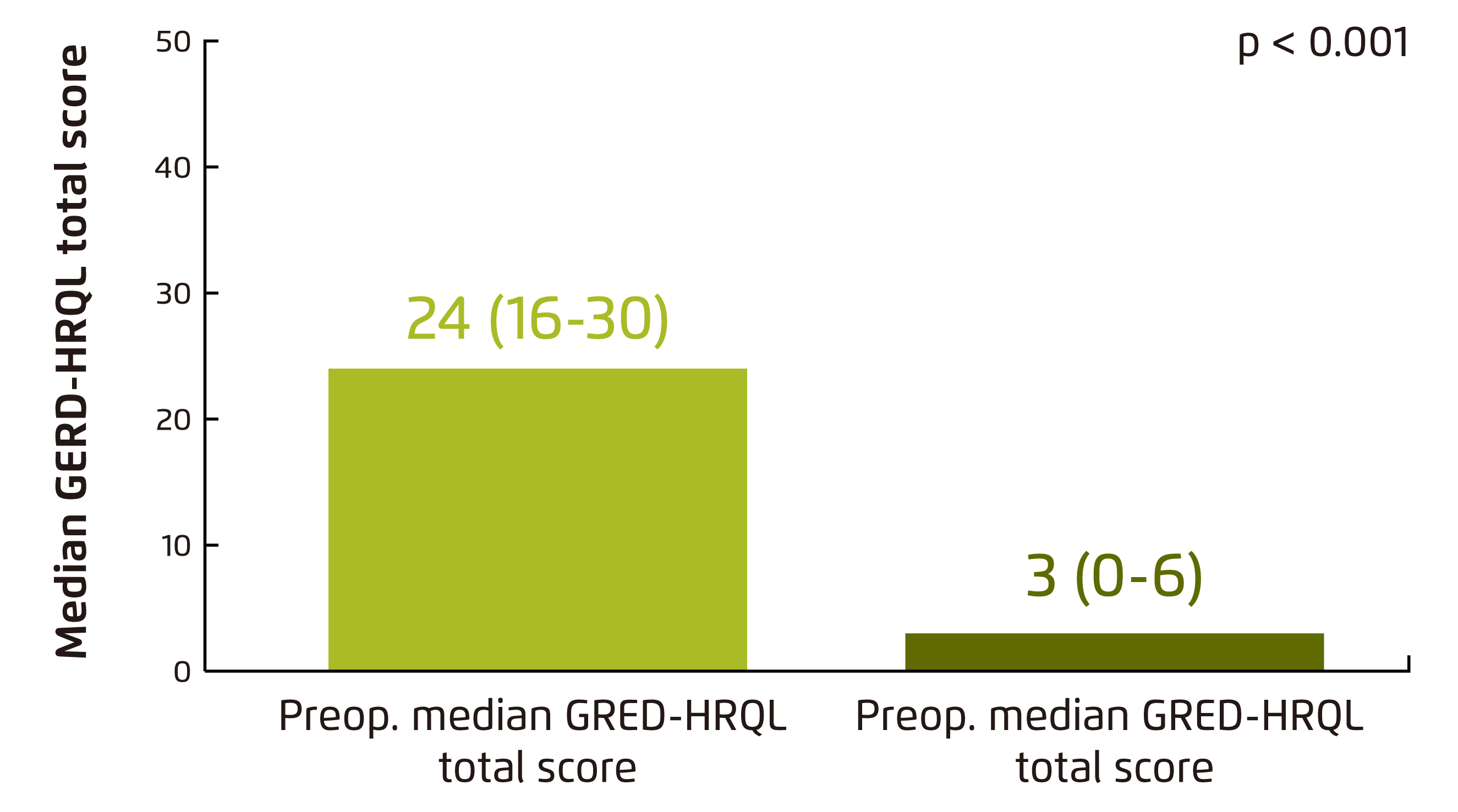

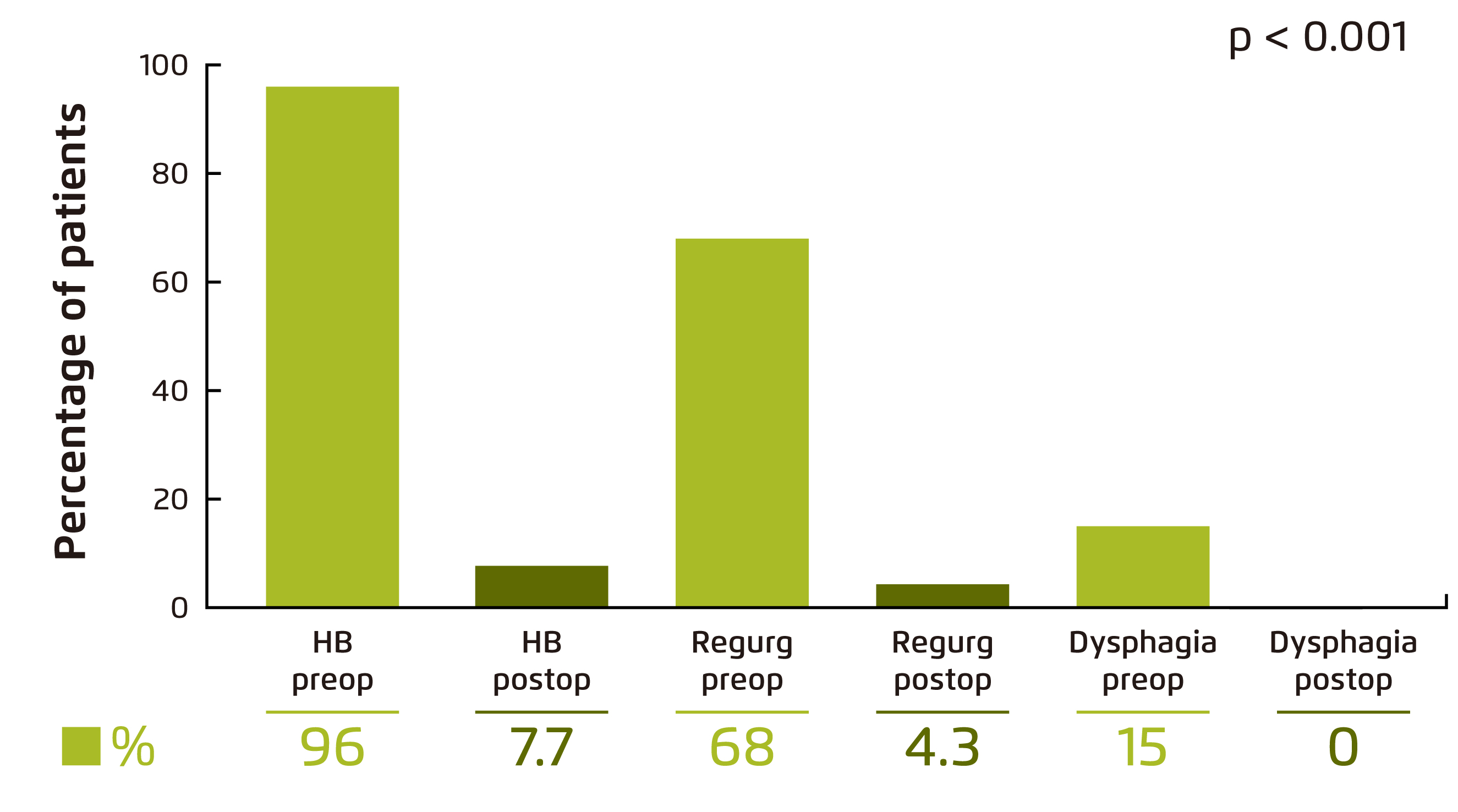

The clinical benefits of MSA have been evaluated in previous clinical studies. For instance, Schwameis et al (2018) demonstrated in a retrospective review involving 68 patients underwent MSA that the post-operative GERD-Health-related Quality of Life (GERD-HRQL) score was significantly reduced upon a median follow-up of 13 months as compared with pre-operative score (p < 0.001), where a lower GERD-HRQL score indicates a better quality of life (Figure 2)10. In particular, pre-operative GERD symptoms including heartburn (HB), regurgitations and dysphagia were significantly relieved (p ≤ 0.001, Figure 3). Although post-operative new-onset dysphagia was reported in 37% of patients, the overall outcome was rated excellent or good in 89% of patients10.

The long-term safety and efficacy of MSA treatment was evaluated in a recent study involving 124 patients implanted with MSA device and were followed from 6 to 12 years. The results demonstrated that 74.2% of patients did not report any oesophageal symptom and significant decrease in mean GERD-HRQL score was observed, from 19.9 at baseline to 4.01 at the latest follow-up (p < 0.001), with 89% of patients achieving pH normalisation. Further, PPIs were discontinued in 79% of the patients11. The results thus indicated that MSA is a safe and effective treatment for controlling reflux symptoms, with sustainable efficacy.

Figure 2. Comparison of pre- and postoperative median GERD-HRQL total scores10

Figure 3. Symptom relief by MSA10.

Regurg: regurgitations; Preop: pre-operative; Postop: post-operative

MSA vs. LF

While PPIs suppress the production of gastric acid in the stomach to reduce the acidity of refluxed gastric juice and hence relieving the symptoms of heartburn and healing oesophagitis, the reflux of non-acid contents is not controlled. Essentially, non-acid refluxate has been reported to play a role in the pathogenesis of Barrett’s oesophagus12. Therefore, surgical intervention is required to control GERD symptoms in certain cases. LF provides mechanical protection from reflux by reconstructing a structurally defective LES using the patient’s own gastric fundus to restore the barrier function at the EGJ13. LF has been demonstrated to be an effective and durable treatment for GERD and can serve as an alternative to PPIs14.

Former prospective observational study involved 249 patients with either MSA (n = 202) or LF (n = 47) showed that both MSA and LF were effective in controlling reflux (reduction in GERD-HRQL: 20.0 to 3.0 [MSA] vs. 23.0 to 3.5 [LF]), with similar safety and reoperation rates (4.0% [MSA] vs. 6.4% [LF]). Notably, discontinuation of PPIs was achieved by 81.8% of patients after MSA, whereas that after LF was 63.0% (p = 0.009). In addition, significantly lower proportion of patients experienced excessive gas and abdominal bloating after MSA (10.0%) as compared to LF (31.9%, p ≤ 0.001). Further, following MSA, 91.3% of patients were able to vomit if needed, which was significantly higher than those after LF (44.4%, p < 0.001)15.

A recent 3-year prospective observational study including 631 patients with GERD further illustrated the efficacies of MSA and LF that significant reduction in GERD-HRQL were observed (22.0 to 4.6 [MSA, n = 465] vs. 23.6 to 4.9 [LF, n = 166]) and both treatment yielded declined PPI usage from baseline to 3 years after surgery (MSA: 97.8% to 24.2%; LF: 95.8% to 19.5%). Importantly, the intraoperative and procedure-related complication rates for both treatments were low (≤2% for both)16. Hence, based on the results of former trials, both MSA and LF were effective in managing GERD symptoms with favourable safety profiles. Nonetheless, in order to avoid unnecessary dissection and preserve the patient’s native gastric anatomy, MSA is advocated in previous report for patients without Barrett’s oesophagus or a large hiatal hernia15.

Factors Affecting Outcomes of MSA

The efficacies of MSA in controlling GERD symptoms have been evaluated in former research works. Proper selection of the optimal population for MSA would no doubt help achieving the best surgical outcomes in patients treated. Warren et al (2018) retrospectively analysed the clinical data of 170 patients underwent MSA and summarised that, at 48 months after MSA, excellent outcomes were achieved in 47% of the patients and good outcomes were reported in 28%. Importantly, a high body mass index (BMI) of >35 (p = 0.03), structurally defective LES (p = 0.05) and pre-operative LES residual pressure (p = 0.02) were independent significant negative predictors of excellent/good outcome17.

As GERD patients may present with a range of typical or atypical symptoms including throat clearing and breathing difficulties and cough18, in addition to general practitioners and gastroenterologists, other specialties such as otolaryngologists, allergists, and pulmonologists may be involved in GERD management. Particularly, comprehensive diagnostic procedures such as ambulatory pH monitoring, high-resolution manometry, barium swallow, and oesophagogastroduodenoscopy would be required for patients continue experiencing symptoms of heartburn and/or uncontrolled regurgitation. Essentially, optimised referral pathways would ensure favourable treatment outcomes in the management of GERD.

References

1. Park. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2019; 25: 337-9. 2. Talley et al. J Intern Med 2020; : joim.13148. 3. LEE et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 30: 154-64. 4. Buckley et al. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2019; 11: 472-6. 5. Kahrilas et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 1419-25. 6. Maradey-Romero et al. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014; 20: 6-16. 7. Hom et al. Drugs. 2013; 73: 1281-95. 8. Bredenoord et al. Lancet. 2013; 381: 1933-42. 9. Asti et al. Updates Surg. 2018; 70: 323-30. 10. Schwameis et al. World J Surg 2018; 42: 3263-9. 11. Ferrari et al. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 13753. 12. Cheng et al. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17: 3060-5. 13. Spivak et al. World J. Surg. 1999; 23: 356-67. 14. Grant et al. BMJ 2013; 346. DOI:10.1136/bmj.f1908. 15. Riegler et al. Surg Endosc 2015; 29: 1123-9. 16. Bonavina et al. Surg Endosc 2020; 1: 3. 17. Warren et al. Surg Endosc 2018; 32: 405-12. 18. Ward et al. Surg Endosc 2019; : 1-7.