Editor-in-Chief, V·Pulse

Urticaria, also known as hives, is a common dermatologic condition characterised by pruritic, erythematous, and elevated plaques. Another manifestation associated with urticaria is angioedema, involving deeper blood vessels. These two conditions can sometimes coexist. The disease burden of urticaria substantially affects not only patients' physical wellbeing but overall quality of life (QoL)1, whereas the socioeconomic impact of the disease is significant as well. Thus, effective and timely management of urticaria is paramount to mitigate its adverse outcomes. The purpose of this article is to review the clinical issues related to urticaria and highlight recent pharmacological advancements against the disease.

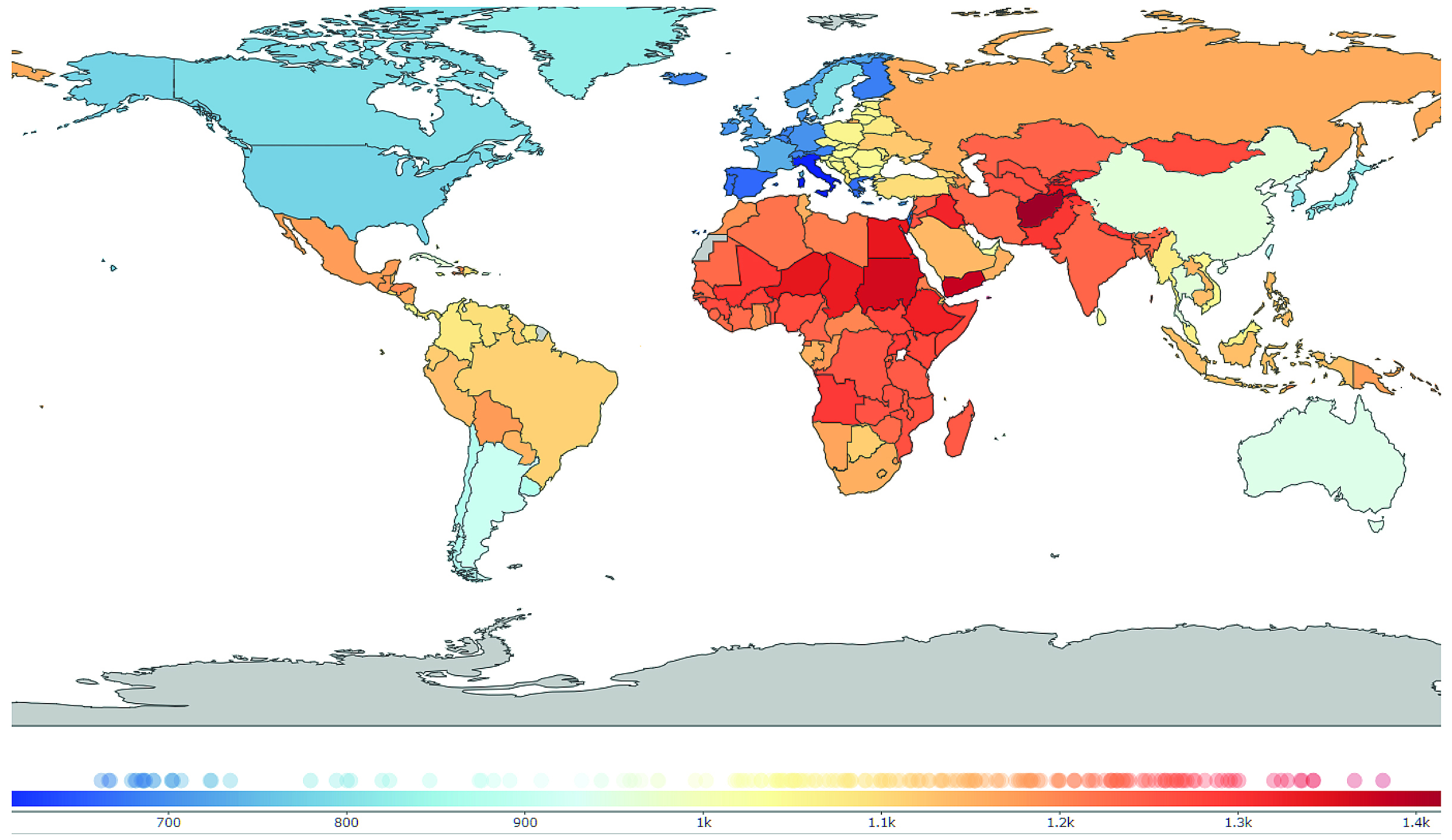

Urticaria is a significant global health issue, with 160 million global incidence cases and 86 million global prevalence in 2017. While the distribution of the burden of urticaria exhibited marked geographical heterogeneity, it has been reported that a lower gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was associated with a higher prevalence and incidence of urticaria (p<0.001, Figure 1). Essentially, the strongest growth in disease burden was observed in South Asia, but a decline was noted in the high-income Asia Pacific2.

Figure 1. Global distribution of urticaria in 20172, prevalence of urticaria per 100,000 population

Although a comprehensive epidemiological data on urticaria in Hong Kong is yet to be available, the population-based study involving 41,041 participants (17,563 male and 23,478 female participants) in 35 cities in mainland China by Li et al. (2022) revealed that the lifetime prevalence of urticaria was 7.30%, with 8.26% in female and 6.34% in male individuals (p<0.05). Additionally, the point prevalence of urticaria was 0.75%, with a significantly higher value in females (0.79%) than in males (0.71%, p<0.05). Notably, concomitant angioedema was found in 6.16% of patients3.

Moreover, the findings in the study by Li et al. aligned with the global data that the burden of urticaria is higher in females than in males, with urticaria cases declining with age, especially in children aged 1 to 14 years, and picking up among the older adults between 50 and 69 years old2. Apart from gender and age, Li et al. reported that living in urban areas, exposure to pollutants, suffering from anxiety and depression, and a family history of allergy were significantly (p<0.01) associated with a higher risk of urticaria3.

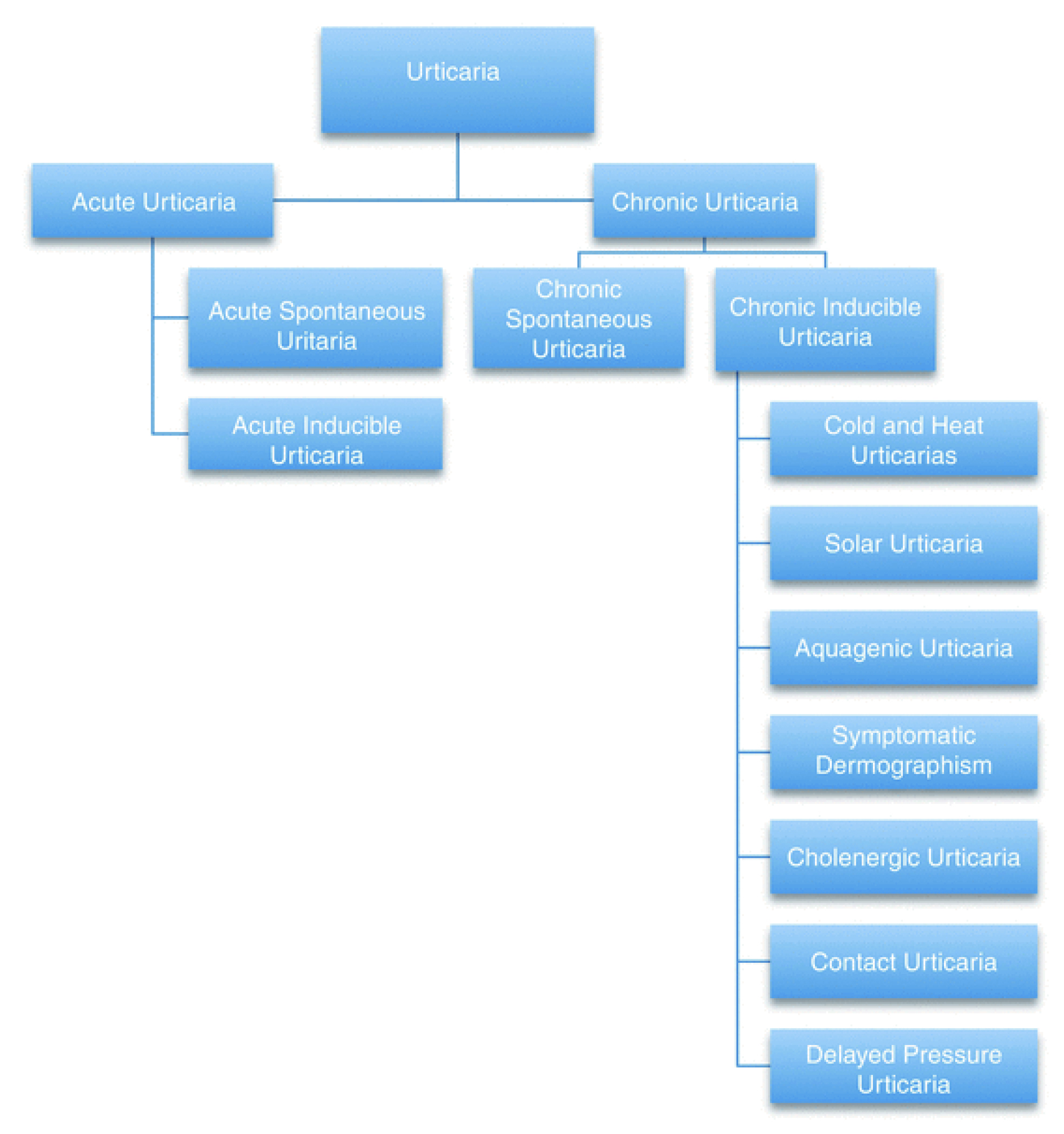

There are various subtypes of urticaria, which exhibit different clinical manifestations. Remarkably, two or more different subtypes of urticaria can coexist in any patient. Based on the EAACI/GA²LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI guideline for the management of urticaria, urticaria is classified based on its duration, as acute or chronic, and the role of definite triggers, as inducible or spontaneous4.

Acute urticaria is defined as the occurrence of wheals, angioedema, or both for 6 weeks or less, whereas chronic urticaria is defined as a condition with symptoms that occur for more than 6 weeks. Chronic urticaria can further classified into chronic inducible urticaria (CIndU), which is characterised by definite and subtype-specific triggers of the development of symptoms, or chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), which triggers are not definite, as their presence does not always induce symptoms and symptoms may also occur without them (Figure 2)4.

Figure 2. Classification of urticaria

Urticaria, regardless of acute and chronic, is a mast cell–driven disease characterised by hives and angioedema. Mast cell activation induces degranulation of vasoactive substances such as histamine, platelet-activating factor, prostaglandins (PGs), and leukotrienes, as well as other proinflammatory mediators, including cytokines and chemokines. Subsequently, vasodilatation and an increase in the vascular permeability occur, facilitating plasma extravasation and recruitment of inflammatory cells. Besides, pruritus is induced by stimulation of sensory skin nerves. Since there are different types of receptors in mast cell membranes, mast cell activation can be driven by various triggers, which differ between acute and chronic urticaria5.

A former report suggested that the lifetime prevalence of acute urticaria is approximately 20% of the population, and the prevalence of CSU is reported to be 0.5–1%6. In contrast, acute spontaneous urticaria was the most common form in mainland China, with a lifetime prevalence of 5.95%, followed by CSU (1.29%), whereas the lifetime prevalence of chronic urticaria was 1.80%3.

Urticaria imposes a significant burden on patients, particularly those with chronic urticaria. Urticaria is characterised by pruritic pink-to-red papules and plaques typically with central pallor. These can vary in size and shape as the plaques coalesce together. Some patients may present with angioedema in addition, or even just angioedema. Angioedema consists of swelling of the deep dermis, subcutaneous tissue, and mucous membranes, and can be painful apart from pruritic5.

Furthermore, urticaria can be associated with other diseases. As per Li et al., patients with urticaria were associated with a higher risk of eczema (23.78% vs 13.55%, p<0.01), asthma (2.46% vs 1.15%, p<0.01), allergic conjunctivitis (2.76% vs 0.79%, p<0.01), allergic rhinitis (19.39% vs 9.51%, p<0.01), food allergy (14.53% vs 4.45%, p<0.01), and drug allergy (11.61% vs 5.17%, p<0.01), thyroid disease (3.20% vs 1.42%, p<0.05) and Helicobacter pylori infection (2.58% vs 1.16%, p<0.05) as compared to the population without urticaria3.

Besides physical symptoms, a recent study by Abdel-Meguid et al. (2024), including 25 patients with chronic urticaria and 25 healthy controls, reported that 72% of the patients had depression and 92% had anxiety. Using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), patients with chronic urticaria had significantly longer sleep latency onset, shorter total sleep duration, lower sleep efficiency and higher PSQI scores compared to controls7. Hence, the results suggested that chronic urticaria highly affects the QoL of patients and is associated with higher levels of anxiety, depression and poor sleep quality.

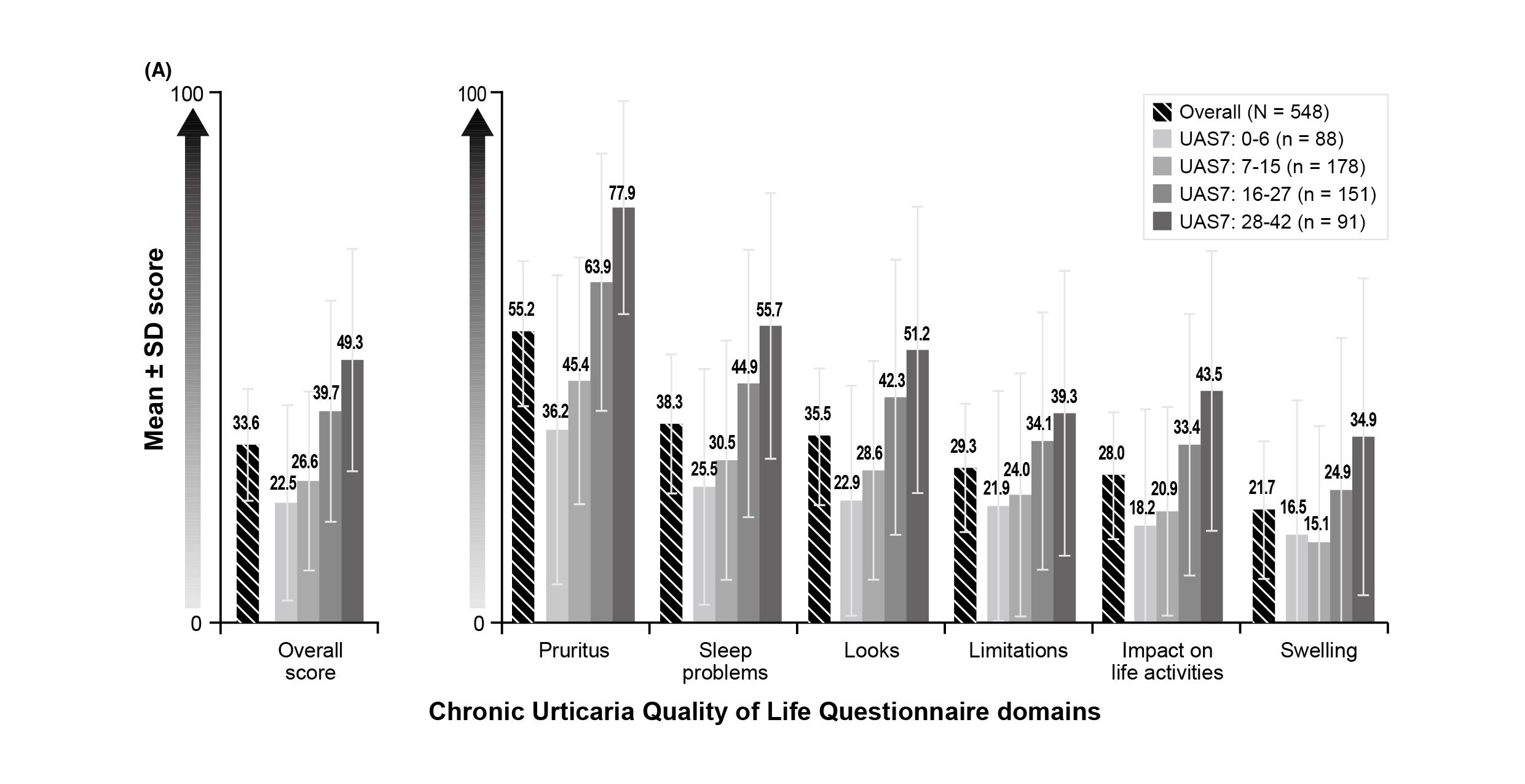

Apart from symptoms, patients’ overall QoL will be influenced. For instance, the real-world cohort study by Maurer et al. (2017), which included 673 adult patients with CSU whose symptoms persisted for ≥12 months despite treatment, reflected that the most affected domains of the Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire (CU-Q2oL) were pruritus, sleep problems, and looks (Figure 3). Essentially, 56.5% of the reporting employed patients indicated that the mean absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment were 6.1%, 25.2%, and 26.9%, respectively, over the previous 7 days8.

Figure 3. Impact of CSU on health-related QoL8, UAS7: Urticaria Activity Score over 7

The medical utilisation related to urticaria was evaluated in the cross-sectional analysis using insurance claims by Zazzali et al. (2012), which included 6,019 patients who had claims consistent with CSU. 56% of patients had primary care physicians as their usual source of care, 14% had allergists, and 5% had dermatologists. 67% of patients used prescription antihistamines, 54% used oral corticosteroids (OCSs), 24% used montelukast, and 9% used oral doxepin. Antihistamine users received a mean of 152 days of prescription antihistamines, OCS users 30 days of OCSs, montelukast users 190 days of montelukast, and oral doxepin users 94 days of doxepin9. Accordingly, the utilisation of medical care and medications associated with urticaria is significant. Notably, given the known risks of OCSs, patients who receive the medication may be exposed to the risk of treatment-related adverse events.

The economic burden of urticaria is substantial. Sánchez-Borges et al. (2021) reviewed that the chronic urticaria-related cost was reported up to US$2050 per year per patient in the United States, having a huge personal and familial impact. In particular, an observational study including 36 patients with chronic urticaria in Mexico by Arias-Cruz et al. (2018) indicated that the impact of the disease on QoL was significantly (p=0.017) associated with monthly income; the lower the income, the more the QoL will be affected10. Thus, the adverse impact of urticaria is extensive, affecting not only the patients but also their families, as well as the healthcare system and society.

In a patient with a clinical suspicion of urticaria, the first step is to classify it into acute urticaria or chronic disease. Since acute urticaria is self-limiting, no complementary tests are needed in general. Nonetheless, identifying the triggers is helpful to eliminate the symptoms5.

As per the EAACI/GA²LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI guideline, the diagnostic workup in CSU has seven major aims. They are to confirm the diagnosis and exclude differential diagnoses; to look for the underlying causes; to identify relevant conditions that modify disease activity; to check for comorbidities; to identify the consequences of CSU; to assess predictors of the course of disease and response to treatment; and to monitor disease activity, impact, and control4.

In all CSU patients, the guideline recommended the diagnostic workup to include a thorough history, physical examination (including review of pictures of wheals and/or angioedema), basic tests, and the assessment of disease activity, impact, and control. In particular, the basic tests include a differential blood count and C-reactive protein (CRP) and/or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), in all patients, and total IgE and IgG anti-thyroid peroxidase (IgG-anti-TPO), in patients in specialist care. Based on the results obtained by these measures, further diagnostic testing may be performed as indicated4.

The goal of urticaria treatment is to treat the disease until it is gone and as efficiently and safely as possible, complete control and normalising quality of life. Pharmacological agents are directed at preventing mast cell degranulation and/or the effects of mast cell mediators released. Importantly, treatment should follow the basic principles of treating as much as needed and as little as possible, taking into consideration that the activity of the disease may vary4.

The EAACI/GA²LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI guideline advocated a 2nd generation H1-antihistamine as first-line treatment for all types of urticaria. In patients with chronic urticaria unresponsive to the standard-dosed 2nd generation H1-antihistamines, up-dosing of the 2nd generation H1-antihistamine up to fourfold is recommended as the second-line treatment before other treatments are considered. While 2nd generation H1-antihistamine is recommended to be taken regularly for the treatment of chronic urticaria, the guideline suggests against using different H1-antihistamines at the same time or using higher than fourfold standard-dosed4.

Omalizumab is the only other licensed treatment in urticaria for patients who do not show sufficient benefit from treatment with a 2nd generation H1-antihistamine and thus is recommended as the third-line therapy. In cases where omalizumab fails to provide sufficient benefit, ciclosporin should be considered. Furthermore, short courses of rescue systemic glucocorticosteroids can be considered in patients with an acute exacerbation of chronic urticaria, but are not recommended for long-term use due to the risks of side effects4.

The therapeutic landscape for urticaria is evolving rapidly, driven by advances in biologics and small-molecule inhibitors. For instance, dupilumab has been approved for atopic dermatitis (AD), asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, eosinophilic esophagitis, and most recently for prurigo nodularis. In the phase 3 LIBERTY-CSU CUPID trial (2024), involving patients with symptomatic CSU despite H1-antihistamine, UAS7 (difference: -8.5, p=0.0003, Figure 4A) and Itch Severity Score (ISS7, difference: -4.2, p=0.0005, Figure 4B) were improved in omalizumab-naïve (n=138) patients at 24 weeks with dupilumab versus placebo. Remarkably, dupilumab also improved UAS7 (difference: -5.8, p=0.0390), with a numerical trend in ISS7, in omalizumab-intolerant/incomplete responders (n=108)11. Hence, the findings suggested that dupilumab reduced urticaria activity by reducing itch and hives severity in omalizumab-naive patients with CSU uncontrolled with H1-antihistamine.

-01.jpg)

Figure 4. Urticaria activity, itch severity, and hives severity at week 24 in omalizumab-naïve patients from the LIBERTY-CSU CUPID trial11, BL: baseline

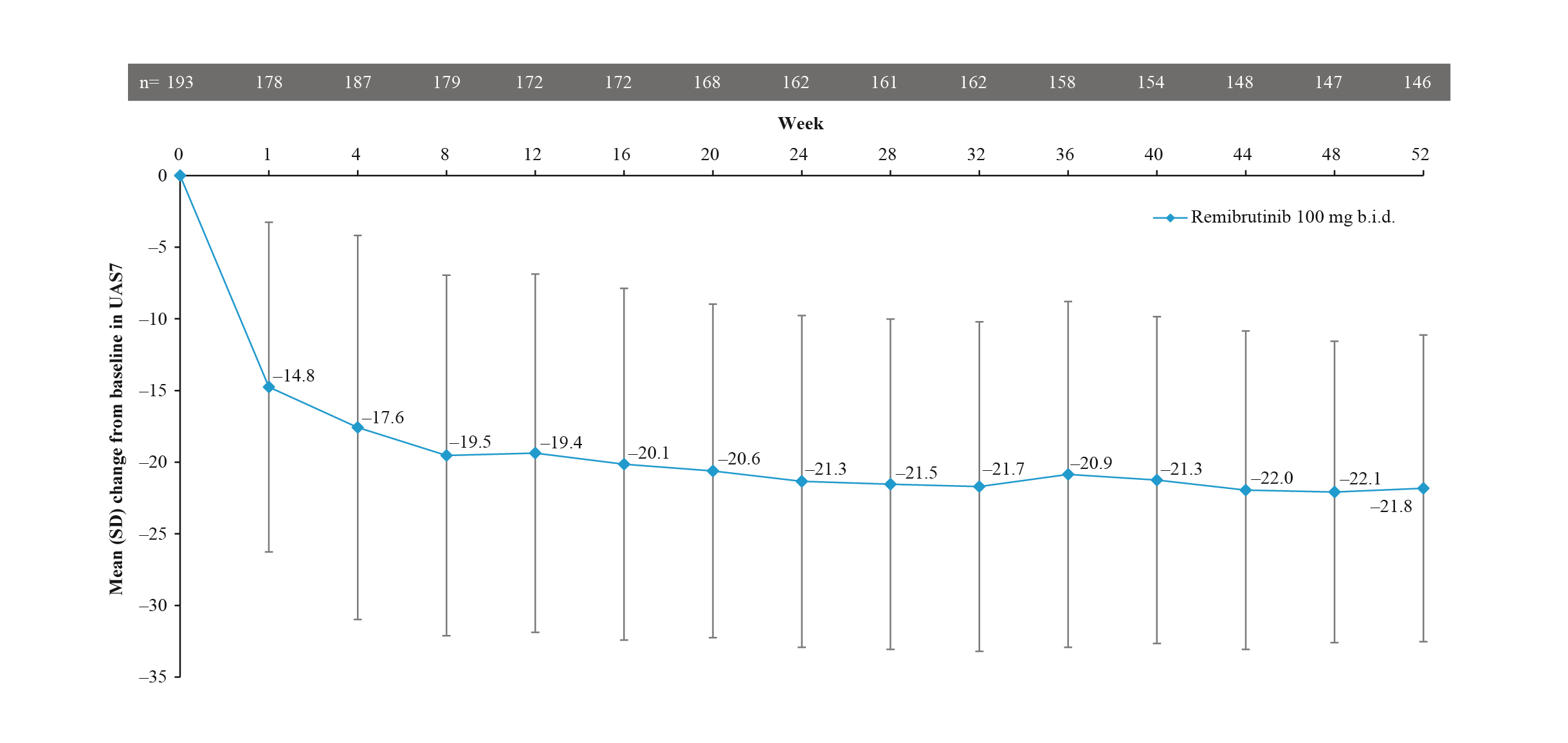

Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK), expressed in mast cells and basophils, is a downstream effector participating in the pathway for mast cell degranulation and release of histamine, resulting in signs and symptoms of CSU such as hives and itch. Thus, BTK inhibitors have been investigated for their ability to inhibit mast cell and basophil activation. The recent phase 2b trial by Jain et al. (2024) demonstrated that remibrutinib, an oral, highly selective BTK inhibitor, yielded a decrease in UAS7 patients with CSU from a baseline of -17.6 and -21.8 at week 4 and 52, respectively (Figure 5). In addition, UAS7=0 was achieved in 28.2% at week 4 and 55.8% at week 52, whereas UAS7≤6 was achieved in 52.7% and 68.0% of patients at week 4 and 52, respectively12. Based on the demonstrated efficacy and safety profile, remibrutinib would offer a fast and sustainable disease control in patients with CSU.

Figure 5. Change from baseline in UAS7 during the remibrutinib treatment period12

Apart from therapeutics under clinical trials, there are potential agents against urticaria at an early stage of development. Of note, mas-related G protein-coupled receptor X2 (MRGPRX2) is a cell surface receptor present on mast cells, and activation of MRGPRX2 leads to mast cell degranulation independent of IgE. Interestingly, MRGPRX2 inhibitors directly block the receptor and its downstream signalling pathway, suggesting their potential as a future target for treating urticaria.

A recent in vitro study by Wollam et al. (2024) demonstrated that MRGPRX2 antagonists potently inhibited agonist-induced MRGPRX2 activation in vitro across species and inhibited agonist-induced mast cell degranulation in all mast cell types tested. Orally administered antagonists demonstrated excellent in vivo efficacy to inhibit agonist-induced degranulation in both MRGPRX2 KI mice and dogs. Furthermore, MRGPRX2 antagonists dose-dependently inhibited agonist-induced degranulation in ex vivo human skin13. The findings supported the potential therapeutic utility of MRGPRX2 antagonists as a novel treatment for mast cell-mediated diseases, including urticaria.

Urticaria is a complex, multifaceted condition with significant pathophysiological, psychological, and socioeconomic impacts. Better understanding of the biomedical basis of the disease, coupled with the development of innovative therapies, is transforming the management strategies and improving treatment outcomes. However, there are practical challenges hindering optimal overall wellbeing of patients, such as in ensuring equitable access to novel treatments, particularly in lower-income populations. In summary, continued research on the pathology of urticaria and therapeutics, public health initiatives, and global collaboration are essential to reduce the burden of the disease and enhance the QoL for patients.

References

1. Pu et al. J Glob Health 2024; 14. DOI:10.7189/JOGH.14.04095. 2. Peck et al. Acta Derm Venereol 2021; 101: 795. 3. Li et al. Chin Med J (Engl) 2022; 135: 1369–75. 4. Zuberbier et al. Allergy 2022; 77: 734–66. 5. Salman et al. Curr Treat Options Allergy 2023; 10: 130–47. 6. Barzilai et al. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, Vol 12, Page 7482 2023; 12: 7482. 7. Abdel-Meguid et al. J Public Health Res 2024; 13. DOI:10.1177/22799036241243268/SUPPL_FILE/SJ-DOCX-1-PHJ-10.1177_22799036241243268.DOCX. 8. Maurer et al. Allergy 2017; 72: 2005. 9. Zazzali et al. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology 2012; 108: 98–102. 10. Arias-Cruz et al. Rev Alerg Mex 2018; 65: 250–8. 11. Maurer et al. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2024; 154: 184–94. 12. Jain et al. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2024; 153: 479-486.e4. 13. Wollam et al. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2024; 153: AB62.