MBChB, MD, FRACP, FHKCP, FHKAM

Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology,

Department of Medicine,Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

The Liver Transplant Center, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

Vice President, Hong Kong Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

Moving Forward and Beyond - What’s Next for HCV in Hong Kong

Viral hepatitis is a global public health burden and it is estimated that 71 million people worldwide are infected with the chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV)1. In Hong Kong, although <0.5% of the general population carry HCV, chronic hepatitis C (CHC)-related liver diseases have been an important disease indication for liver transplantation and there has been an increasing trend in local HCV infection over recent years2. With the appearance of oral direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), the field of HCV treatment has been dramatically revolutionised in terms of efficacy, tolerability and simplicity3. Dr. James Fung, an Honorary Clinical Associate Professor at HKU and the Transplant Hepatologist at Queen Mary Hospital, was invited to discuss how the management of HCV in Hong Kong transformed significantly during the past years by ways of introducing DAAs that shaped the current treatment algorithm for HCV care, and whether this spell will be the end of the road for the viral infectious disease and all things related.

Current Handling of HCV Treatment

With the current approach of hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment, Hong Kong has aligned itself with the World Health Organization (WHO) strategy to eliminate viral hepatitis as a major public health threat by 20301. Dr. Fung mentioned that treatment has gradually expanded to include not only those patients with advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis, but also F2 fibrosis. Additionally, there is work on microelimination of HCV in high risk groups, such as those undergoing haemodialysis.

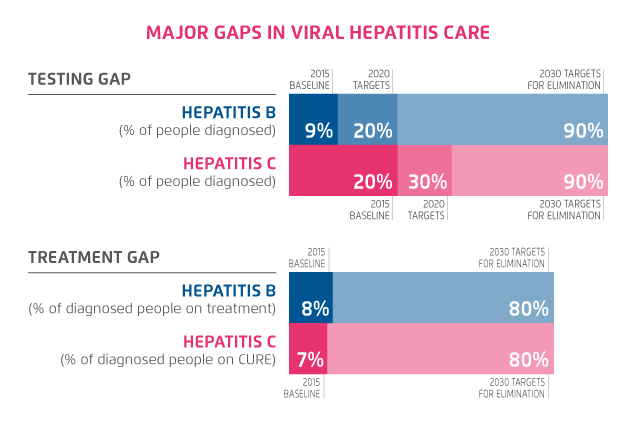

However there is still a long way to go if Hong Kong were to achieve the WHO goal by 2030 (Figure 1)4. This includes expanding the treatment criteria to include all patients irrespective of their fibrosis stage1. Perhaps the biggest hurdle is identifying all the undiagnosed HCV carriers, and establishing a screening strategy, with subsequent linkage to care, as suggested by Dr. Fung.

Figure 1. WHO Viral Hepatitis Elimination Goal by 20304 (adapted from WHO)

The Right Choice of Direct-Acting Antiviral (DAA) Regimen

Prioritising the choice of regimen based on efficacy, safety, simplicity and cost are important when making a decision to start antiviral therapy according to Dr. Fung. Fortunately, the pangenotypic DAAs available now are highly efficacious, with sustained virological response (SVR) rate approaching 100%3. Safety is always of paramount importance for the patient, and overall, the DAAs are generally very safe3. However, “we do have to take into considerations any possible drug-drug interaction (DDI), and also any underlying significant co-morbidities that might be important”, stated Dr. Fung.

The simplicity of the regimen is important, especially for patient compliance, and if the patient is already taking multiple medications for other conditions3.

Currently, the simplest regimen is in the form of a fixed-dose capsule taken once daily. Dr. Fung addressed that simplicity for the clinician is also important, whether the regimen is dependent on the HCV genotype (GT) and further additional testing is required before starting treatment.

Although cost has been a major consideration point in the past, especially with the first generation DAAs, they are far less prohibitive now since they have been available for longer, and also with more regimens on the market5.

The Sofosbuvir (SOF)-Based Regimen

The advantages of a SOF-based regimen have been with the use of a single fixed-dosed capsule, with SOF and ledipasvir, and now, with SOF and velpatasvir (SOF/VEL)6. This is the simplest regimen to date and has revolutionised HCV treatment from requiring large number of pills to only taking a single pill once daily. Another advantage is that since SOF-based regimens do not contain a protease inhibitor, and can be used in patients with advanced liver disease, including decompensated cirrhosis7. This is an important group of patients who need treatment the most, but previously had no available treatment option.

DDIs is an important consideration and in liver transplantation, DAAs may have significant DDIs with the immunosuppressive drugs, therefore close monitoring and adjustment of immunosuppression is required. Fortunately, SOF-based regimens have less DDIs8.

Moreover, studies have now demonstrated the safety of SOF-based regimens in those with an eGFR <30 mL/min with a SVR rate of 97% and thus can now be used in patients with eGFR <30 mL/min7.

Given the simplicity of a SOF-based regimen, this can be recommended for the majority of patients. For those who prefer a shorter duration of therapy of 8 weeks, a combination of glecaprevir and pibrentasvir can be recommended, although the trade-off will be a higher pill burden9. However, SOF should not be prescribed with amiodarone10 and it is also best to avoid proton-pump inhibitors during treatment.

Dr. Fung reassured that, “we are certainly getting close to having a single regimen which can be used to treat the full range of patient population”. As the FDA has lifted the restriction on the use of SOF-based regimens in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), SOF-based regimens can now be used in patients with hepatic/renal impairment7,11.

Further CHC Management in Hong Kong

The program for eliminating HCV infection in Hong Kong should include improving access to care, screening strategies, and preventive measures for high-risk groups. Hong Kong has aligned itself with the WHO 2030 goals, with the establishment of a Steering Committee on Prevention and Control of Viral Hepatitis12. The treatment criteria for DAA has widened from F3 to F2 fibrosis, and in the future, will likely be all-inclusive. Currently, all post-liver transplant patients can receive DAAs13. In addition, microelimination strategies have been formulated for those on haemodialysis, and nurse-led clinics will also alleviate the increasing workload that is anticipated with increasing number of patients diagnosed.

Dr. Fung stressed that after treating all available patients on hand, the major hurdle will be to identify undiagnosed individuals by screening at-risk groups, and then have an effective linkage to care system established. Neighbouring countries such as Taiwan and Singapore that have been performing well so far have robust primary care foundation to build upon. Therefore, the engagement of a primary care provider seems to be an essential component, and tertiary care hospitals may need to adopt a role in training and prove support to participating primary care providers.

Case Sharing by Dr. Fung

The patient is a 61 year old Chinese man who had chronic hepatitis C (GT 1b). The HCV was likely acquired during a period of intravenous drug use in his late teens. He was diagnosed back in 2008 with established cirrhosis, developed hepatic encephalopathy in 2014, and was subsequently diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma in February 2017. He received a living donor liver transplantation in April 2017. He did not receive antiviral therapy prior to transplant, and declined combination peg-intereferon with ribavirin when he was first diagnosed. Post-transplant HCV recurrence is universal after transplantation for those who are viraemic at the time of transplant, and the disease tends to be more severe with rapid progression to cirrhosis if left untreated. The patient was on long-term immunosuppression medication including tacrolimus. Some DAA regimens can have significant drug-drug interactions requiring dramatic reductions in the immunosuppression dose and more frequent visits with careful therapeutic drug level monitoring. Therefore it was important to choose a regimen that had minimal DDIs with the existing medications.

Treatment Choice

Post-transplant patients are often on multiple medications due to their underlying co-morbidities. For instance, this patient was already on 5 different medications at the time, so it was important to choose a regimen with lower pill burden. SOF/VEL, being a fixed-dose capsule taken once daily, was the simplest regimen to be given for a 12 week duration. The primary outcome would be the achievement of SVR12. This means that the viral load remains undetectable at 12 weeks after completion of therapy, and is equivalent of a cure. The baseline viral load prior to treatment was 2,770,000 IU/mL. After 4 weeks of treatment, the HCV RNA was already undetectable, and remained undetectable 12 weeks after completion of treatment. Therefore the patient achieved SVR12.

Challenges during Treatment

The major challenge with managing post-transplant patients is the potential DDIs, especially with the immunosuppressive drugs. Often they need meticulous drug therapeutic level monitoring and adjustment of doses, and are at risk of drug toxicity or developing allograft rejection. Fortunately, there was no significant DDIs with the current regimen. Renal impairment is also common in post-transplant patients, due to pre-existing renal disease, the side effects of immunosuppression, and the high prevalence of hypertension and diabetes. The patient had chronic renal impairment with an eGFR of 59 which remained stable throughout treatment. Contrary to previous recommendations, the current regimen has shown to be safe even in patients with renal impairment.

Final Remarks

Naturally the patient was extremely grateful that his HCV was eradicated after being chronically infected for many decades. After so many years of HCV carriage, it seems unbelievable to him that it can be so easily cured by just taking a pill for 3 months.

References

1. WHO Fact Sheet 2019. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c. Accessed on: 25/03/2020. 2. Hepatitis C. Department of Health Hong Kong. Available at: https://www.info.gov.hk/hepatitis/english/hep_c_set.htm. Accessed on: 25/03/2020. 3. Zoratti MJ, et al. E Clinical Medicine 2020;18:100237. 4. Global Hepatitis Report Inforgraphics. Available at: https://www.who.int/hepatitis/news-events/global-hepatitis-report2017-infographic/en/. Accessed on: 27/03/2020. 5. Gupta V, et al. Indian J Med Res 2017;146:23-33. 6. Buggisch P, et al. PLoS One 2019;14:e0214795. 7. Cox-North P, et al. Hepatol Commun 2017;1:248-255. 8. Yang YM, et al. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2017;13:477-497. 9. Emmanuel B, et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2:832-836. 10. Back DJ, et al. Gastroenterol 2015;149:1315-1317. 11. FDA Press Announcement 2016. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-epclusa-treatment-chronic-hepatitis-c-virus-infection. Accessed on: 26/03/2020. 12. Viral Hepatitis Control Office. Available at: https://www.hepatitis.gov.hk/english/about_us/about_us.html. Accessed on: 26/03/2020. 13. Bhamidimarri KR, et al. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;13:214-220.