Chief of Rheumatology

Department of Medicine

Tuen Mun Hospital

Caring Mood Disorders in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterised by multi-systemic involvement and the production of autoantibodies. SLE affects mostly women aged between 15 and 45, the period when most people attain their educational and socioeconomic status1. Essentially, SLE has an unpredictable disease course, and may trigger cutaneous lesions, pain and organ damage. In particular, a substantial proportion of SLE flare episodes involve the central nervous system that is under-recognised and misunderstood. Currently, there is no specific biomarker for diagnosis of neuropsychiatric symptoms in SLE (NPSLE). Hence, NPSLE, especially mood disorders, may be undiagnosed if screening for symptoms is not performed in busy clinics. Psychiatric symptoms adversely affect the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of SLE patients2. Thus, in a recent sharing, Dr. Chi Chiu Mok uncovered the essentials of the vicious cycle involving SLE and mood disorders as well as its impacts in various aspects, he also shared his opinions in optimising the management of mood disorders in SLE within local clinical settings.

The Complexity of NPSLE

The definition of neuropsychiatric symptoms in SLE (NPSLE) is a tough challenge owing to the broad spectrum of neuropsychiatric (NP) symptoms that it encompasses, most of which are non-specific. In 1999, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) developed a nomenclature system for 19 different forms of neuropsychiatric involvement in SLE3. Approximately one-third of all NP events are directly attributed to SLE, whereas mood disorders are one of the most frequent NP events reported in SLE patients2. “Subtle depression or mood symptoms are common in SLE patients,” commented Dr. Mok.

Practically, the estimation of NPSLE prevalence is difficult owing to variations in study designs, follow-up periods etc. For instance, it has been reported that major depression is present in 24% of lupus patients, while major anxiety in 37%4. However, in a local investigation by Dr. Mok and co-workers, the prevalence of depressive disorder and anxiety determined through direct interview by designated psychiatrist with DSM-IV protocol was 15.4% and 21.1%, respectively5.

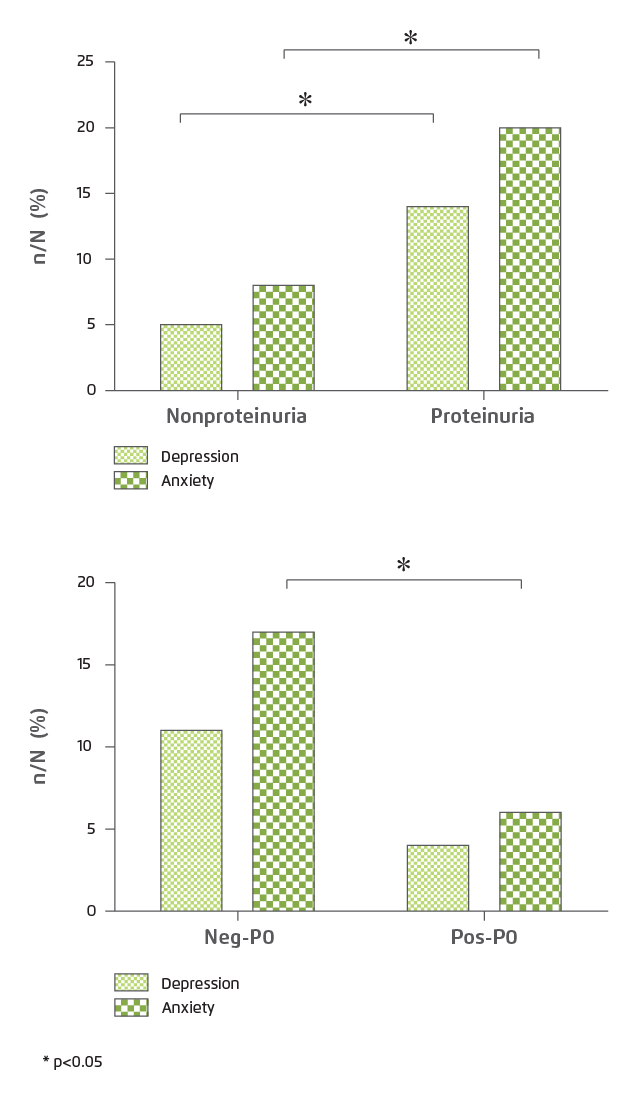

In evaluating risk factors of NPSLE, former review suggested that the association between depression and SLE may be the result from both, the physical effect of autoimmunity on the nervous system and the suffering due to pain and disability. For instance, Bai et al (2016) showed that depression and anxiety were associated with the occurrence of clinical phenotypes of SLE such as proteinuria and negative anti-ribosomal P0 antibody (anti-P0 antibody) (Figure 1)6. However, there are many confounding factors that exist in the SLE population such as disease activity, sleep and physical activity7. On the other hand, due to the substantial proportion of female within the SLE population, Dr. Mok postulated that gender would be associated with the high prevalence of mood disorder in SLE. However, solid evidence confirming the association is yet to be developed. Nonetheless, identifying psychological and physical factors that contribute to NP events in SLE patients is difficult.

Figure 1. Association between emotional disorders and clinical phenotypes of SLE6

Personal Impact of Mood Disorder in SLE

As in the general population and other chronic diseases, SLE patients with mood diseases have worse health-related outcomes. “Mood disorder is one of the reasons for SLE patients changing from full time to part time employment, or even quitting their jobs,” commented Dr. Mok. He further stated that depression triggers a wide spectrum of adverse outcomes leading to higher frequency of public medical service utilisation. This increases burden for both patients and the public medical system. In fact, there are numerous reports suggesting that depressive symptoms are associated with work disability, decreased work productivity8, cognitive dysfunction9, sleep disorder10 and reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL)11.

Particularly, Dr. Mok highlighted the manifestation of fibromyalgia (FM) in illustrating the impact of multiple somatic symptoms triggered by depression. FM is a rheumatic condition characterised by a diffuse chronic pain, hyperalgesia and allodynia. With FM, the transmission of painful stimuli is amplified leading to changes in the perception of pain. However, the aetiology and pathogenesis is not fully understood12. FM is reported to be identified in about 20% of SLE patients13. Dr. Mok commented that FM is more common among Caucasians, whereas its local prevalence is unknown. “FM significantly affects sleep quality, while suboptimal sleep quality contributes to further pain. Therefore, the vicious cycle significantly worsens the quality of life of SLE patients,” he explained.

Suicidal ideation is reported to be associated with mood disorder that, about 45-77% of suicide victims suffered from mood disorder at the time of death. Chronic physical illnesses are well recognised as important risk factors for suicide, whereas SLE patients are at about a fivefold higher risk for committing suicide than expected14. According to a local study by Dr. Mok and colleagues (2014), suicidal thoughts were present in 12% of patients with SLE, and were more intense in patients with depressive symptoms, cardiovascular damage, recent life events and previous suicide attempts15. Besides, it has been reported that comorbid depression in FM and arthritis are major determinants for suicidal ideation16.

In addition to pathological complications, depression is strongly correlated with low treatment adherence among SLE patients, whereas female gender, younger age and more severe depressive symptoms are associated with depressive symptoms among SLE patients17. Treatment adherence is crucial in determining clinical outcomes and healthcare utilisation in SLE. Hence, examining depression and mood disorder symptoms for SLE patients would facilitate improvement in adherence and hence optimise treatment outcomes.

The Vicious Cycle of Mood Disorder and SLE

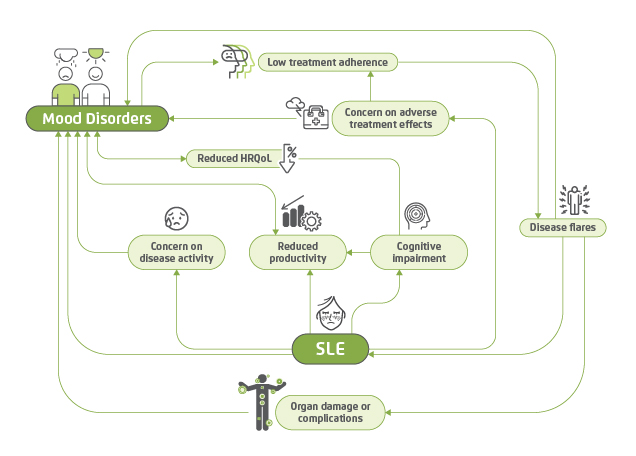

Dr. Mok described that the vicious cycle of mood disorders and SLE is not a single loop but consists of various pathways. “Depression is a common reactive response to chronic illness including SLE. However, depressive symptoms are associated with low treatment adherence, which leads to disease flares. The increased disease activity further intensifies depression,” he addressed. In addition, disease flares would trigger organ damage or complications such as stroke, which leads to mood disorders as well.

“Uncertainty in disease activity and concern on the potential impact of the disease activity and/or treatment-related adverse effects on daily life and work would induce anxiety in SLE patients,” noted Dr. Mok. He further shared that, as a major proportion of SLE patients are young female, the potential impact of SLE on marriage and pregnancy is also a source of mood problems.

Dr. Mok emphasised that HRQoL plays an important role in the vicious cycle that, not only in SLE patients, depression also leads to reduced HRQoL. He suggested that low HRQoL would be associated with depression. Hence, the interaction between mood disorders and reduced HRQoL would be a 2-way direction. Besides, SLE symptoms including FM are reported to reduce HRQoL of patients11.

Importantly, SLE-related pain, fatigue and physical disability reduce work productivity of the patients18. However, former comment suggested that SLE patients with work disabilities have higher depressive symptoms and worse cognitive function8.

Cognitive impairment is present in 80% of SLE patients with 10 years after diagnosis9. Dr. Mok shared that many of his SLE patients reflected to have bad memory even in the non-active disease state. He further quoted that some SLE patients would have smaller brain volume, but the underlying mechanism is still unknown. “Impaired cognitive function would adversely impact work productivity and HRQoL,” added Dr. Mok. Based on Dr. Mok’s opinions and supporting evidence, the vicious cycle of mood disorders and SLE with related adverse impacts is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The vicious cycle of mood disorders and SLE

Difficulties in Controlling SLE-associated Mood Disorder

Although the disease burden on mood disorder in SLE is significant, the diagnosis of the disorder is difficult. Essentially, there is no specific clinical patterns, pathognomonic blood tests, biomarkers and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) abnormalities for mood disorder in SLE. Further, specific neuroimaging pattern for the condition is yet to be identified1. In local public clinical practice, there is no screening for mood disorder in SLE. Dr. Mok estimated that the burden of mood problem among local SLE patients is probably underestimated due to cultural influence. “Chinese patients are less likely to express mood problems as compared to Westerners,” he commented.

Further, Dr. Mok highlighted the current limitation within the public healthcare setting that the current operation in public rheumatology clinics is very busy and the time allowed for each consultation is very limited. Thus, diagnosis of mood disorder during a consultation is difficult. “Only patients with overt symptoms such as bad appetite, obvious weight loss and insomnia will be identified and referred to psychiatrists for follow-up,” stated Dr. Mok. The initial screening of mood disorder in SLE could best be performed by rheumatology nurses through completion of questionnaires in the waiting room. Further investigation of susceptible cases will be done during consultation and subsequently a referral to psychiatrists or clinical psychologists if necessary.

Breaking the Loop in Clinical Settings

In the vicious cycle of mood disorder and SLE, disease activity, HRQoL and mood disorder episodes are the main components. Thus, early diagnosis and treatments targeting the 3 components are needed to break the vicious cycle and hence to improve health outcomes for the patients. For early diagnosis, Dr. Mok commented that structural face-to-face interview between patients and psychiatrists or clinical psychologists according to established protocol such as DSM-IV would yield diagnosis of mood disorders with high specificity, but this practice is currently uncommon in public clinical settings. Instead, he suggested that self-reported questionnaires completed by patients would be helpful in identifying early cases of depression and mood disorder in SLE. In managing SLE patients with mood problems, mental health interventions for depression may increase medication adherence.

It is generally agreed that better control and monitoring of SLE disease activity and potential complications would help relieve mood problems. Thanks to the recent development in medication for controlling SLE, there are biologics which are effective in reducing SLE disease activity, flare rates and prednisone dose in seropositive patients19. Besides, medications for depression and FM are now available and can lead to a better prognosis20.

In addition to disease activity, Dr. Mok highlighted the importance of improving HRQoL. In particular, he addressed the efficacies of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in SLE patients with mood disorder. CBT is a unique category of psychological intervention which could make coping with the disease easier and change patients’ cognitive appraisals of symptoms21. Previous investigations demonstrated that CBT is effective in dealing with patients suffering from SLE and high levels of daily stress as it significantly reduces the incidence of psychological disorders associated with SLE and improves HRQoL22.

The Vital Role of Social Support

Social and family support is essential for successful treatment in SLE patients with mood disorder. From the view of frontline clinician, Dr. Mok appreciated the team work among healthcare professionals from different specialties such as psychiatrists and rheumatology nurses available in the public healthcare system. The team provides a wide scope of treatments and services including counselling for patients in need. “Although the team work may not be available in private clinics, counselling on mood problem in SLE by general practitioners is recommended,” suggested Dr. Mok. He further advised that frontline clinicians can provide social support for SLE patients with mood disorders by recommending peer groups or a community rehabilitation network for self-management programs, which are organised by social workers. The programs are expected to enhance patients’ sense of social support.

In response to the inquiry on how the government could support in optimising mood disorder in SLE, Dr. Mok addressed that more resources are certainly preferred. For instance, currently there is limited number of clinical psychologists available in public hospitals and they need to serve different specialties. Moreover, more nurses for counselling and initial screening of mood disorder are needed to facilitate early diagnosis and subsequent treatment.

The interaction between mood disorder and SLE is highly complicated, whereas the adverse impact of the vicious cycle is extensive and substantial. While disease activity, psychiatric manifestations and HRQoL are the main components of the vicious cycle, diagnostic and therapeutic innovations, cognitive behavioural modification and social support targeting the components are vital to break the loop.

References

1. Tisseverasinghe et al. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20(12). 2. Hanly et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(7):1837-1847. 3. de Almeida Macêdo et al. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37(12):1999-2004. 4. Zhang et al. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1). 5. Mok et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017:589.1-589. 6. Bai et al. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016. 7. Figueiredo-Braga et al. Med (United States). 2018;97(28). 8. Utset et al. Lupus Sci Med. 2015;2(1). 9. Petri et al. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(10):2032-2038. 10. Palagini et al. Lupus. 2014;23(2):115-123. 11. Abu-Shakra et al. Isr Med Assoc J. 2016;18(3-4):144-145. 12. Kasemodel de Araújo et al. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2015;55(1):37-42. 13. Wolfe et al. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(1):82-88. 14. Karassa et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(1):58-60. 15. Mok et al. Rheum (Oxf). 2014;53(4):714-721. 16. Calandre et al. Rheumatol Int. 2018;38(4):537-548. 17. Heiman et al. J Clin Rheumatol. 2018;24(7):368-374. 18. Michaud et al. Rheumatol Ther. 2019;6(3):409-419. 19. Tao et al. Pakistan J Med Sci. 2019;35(6):1680-1686. 20. FDA. Living with Fibromyalgia, Drugs Approved to Manage Pain | FDA. 21. Greco et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(4):625-634. 22. Navarrete-Navarrete et al. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79(2):107-115.