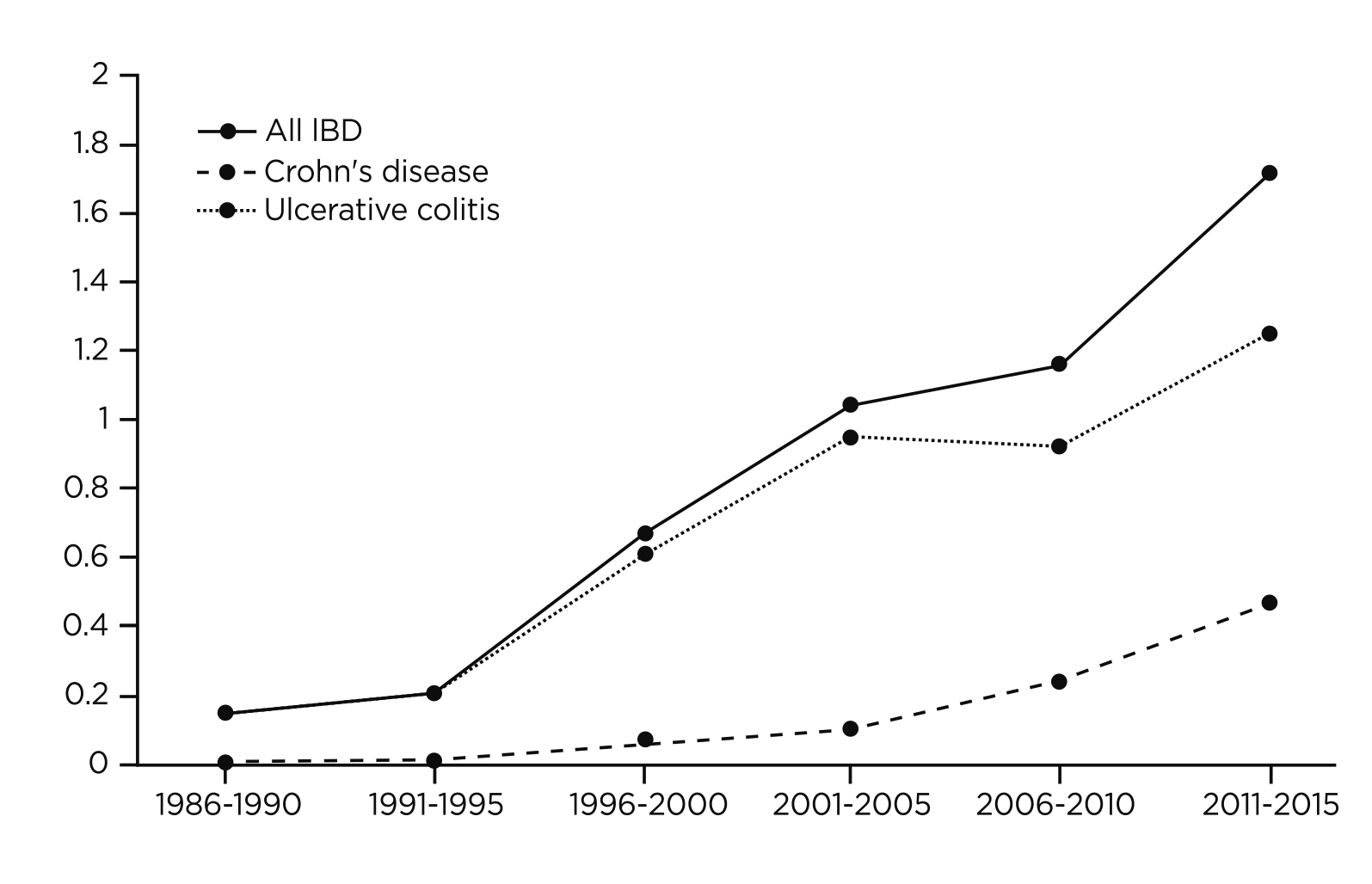

Crohn's disease (CD), similar to ulcerative colitis, causes digestive disorders and both of them are classified as inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD)1. According to epidemiological data, the incidence of CD has been rising in Hong Kong over the past few decades, and this has sparked the public awareness of the condition (Figure 1)2. Notably, patients with CD often experience a pattern of relapse and remission course of their disease3. This not only expedites the structural damage to the bowel, but also creates a detrimental effect on patients' quality of life (QoL)3. Hence, a rapid and robust disease control would undoubtedly improve the prognosis and QoL of CD patients.

Figure 1. Incidence of older adult-onset IBD per 100,000 population in Hong Kong from year 1986 to year 20152 (IBD= inflammatory bowel disease)

Figure 1. Incidence of older adult-onset IBD per 100,000 population in Hong Kong from year 1986 to year 20152 (IBD= inflammatory bowel disease)

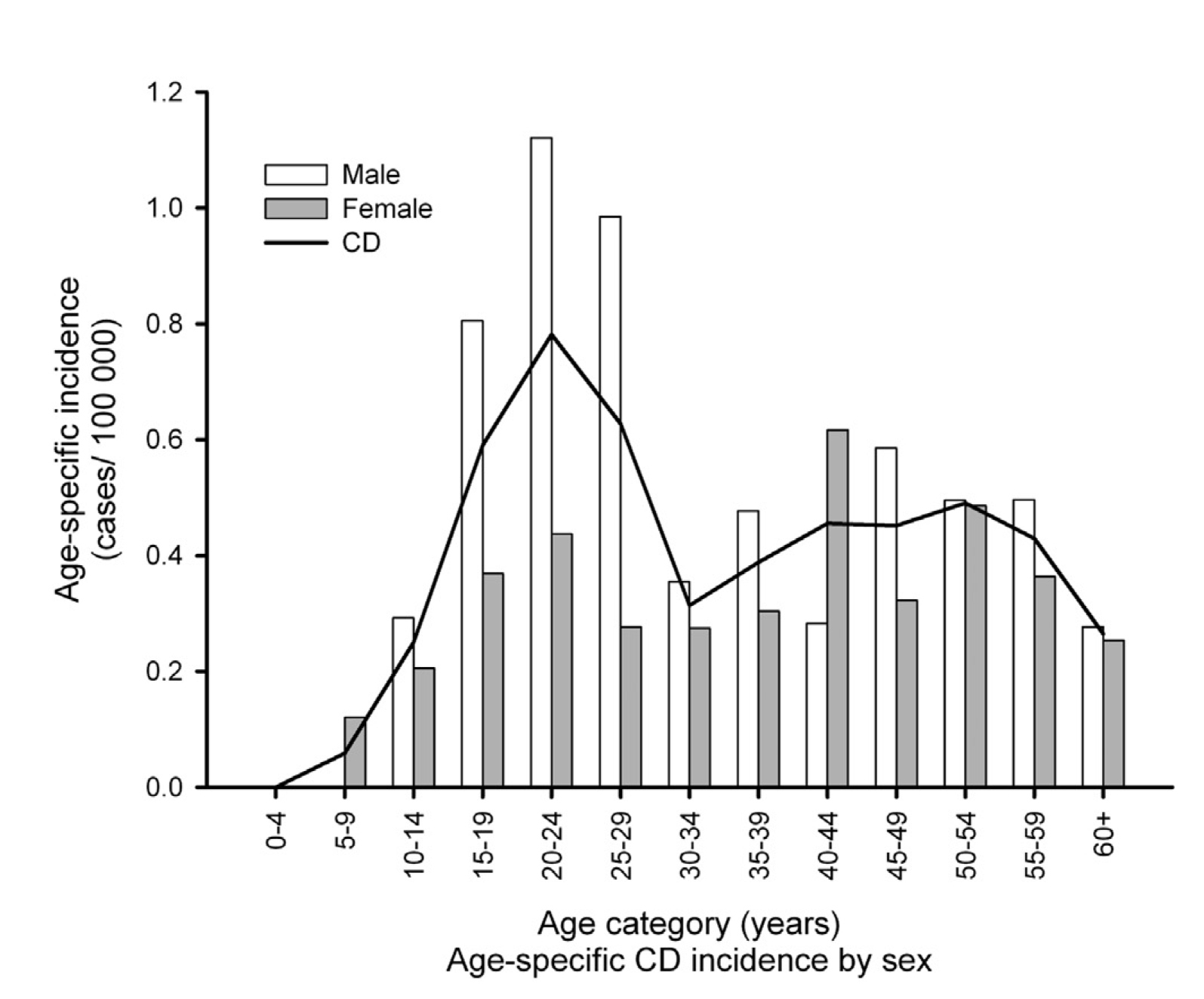

CD is characterised by the transmural granulomatous inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract which can affect individuals of all ages, but the highest incidence rates are observed in males aged between 20 to 29 (Figure 2)4,5. In Hong Kong, the annual overall incidence of CD reported in 2013 was 1.31 per 100,000, which is considered as the third highest in the Asia region5. Patients suffering from CD often presents with chronic diarrhoea, abdominal pain, weight loss and mucus or blood in the stool4. The uncontrolled inflammation may also lead to long-term complications such as fibrotic strictures and intestinal neoplasia6. Considering CD is a progressive GI disorder, patients with CD may complain of gradually worsening of their symptoms that significantly impede their activities of daily living or social lives7. In addition, since symptoms fluctuate over time, the diagnosis remains challenging that patients with CD are often misdiagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)6. Moreover, due to the heterogeneous entity of CD, the diagnosis of CD is considerably delayed, causing an increased risk of bowel stenosis that may require intestinal surgery8.

Figure 2. Age-specific incidence of Crohn’s disease in Asia-Pacific5

Figure 2. Age-specific incidence of Crohn’s disease in Asia-Pacific5

The treatment goals of CD are to reduce the disease progression by successful initiating induction followed by the maintenance of remission9. This helps to reduce the incidence of flare-ups and ultimately leads to a better QoL for the patients9. In general, treatment of CD consists of an induction phase where a high dose of steroids are used for rapid palliation of symptoms, followed by a maintenance phase in which a lower dose of steroid-sparing medication is utilised, particularly anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents and immunosuppressants, for sustaining remission6. However, the treatment failure rate remains high as it is estimated that up to one-third of CD patients are not responsive to the traditional anti-TNF therapy9. Furthermore, a second subset of patients may be initially respond to the traditional treatment, but over time lose the treatment response and become intolerant to these medications9. This treatment uncertainty may heighten CD patient's psychological burden10. Therefore, the unmet treatment needs persist in patients with CD and need to be urgently addressed.

Janus kinase (JAK) serves as a key modulator in the signal transduction pathway of several proinflammatory cytokines that are involved in GI inflammation, and thus offers excellent potential for the treatment of IBD11. One such JAK inhibitor is upadacitinib, which exhibits increased selectivity for JAK1 and can downregulate multiple proinflammatory cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of CD, such as interleukin (IL) and interferon gamma (IFN-γ), making it the first oral medication approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for moderately to severely active CD12,13. Upadacitinib offers a new treatment hope for CD patients who have previously experienced treatment failure, discontinued previous therapies, or are unable to tolerate alternative treatments11.

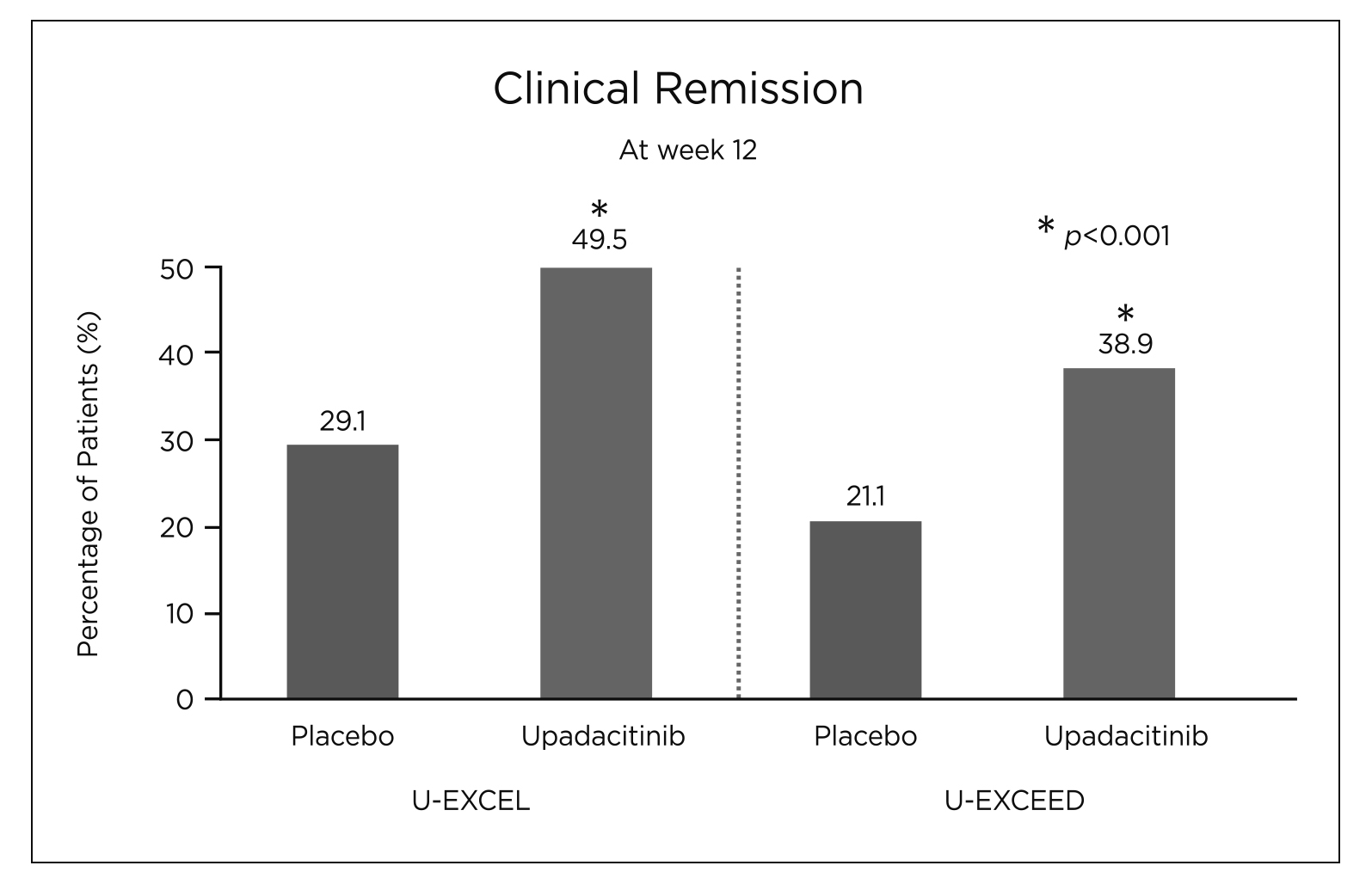

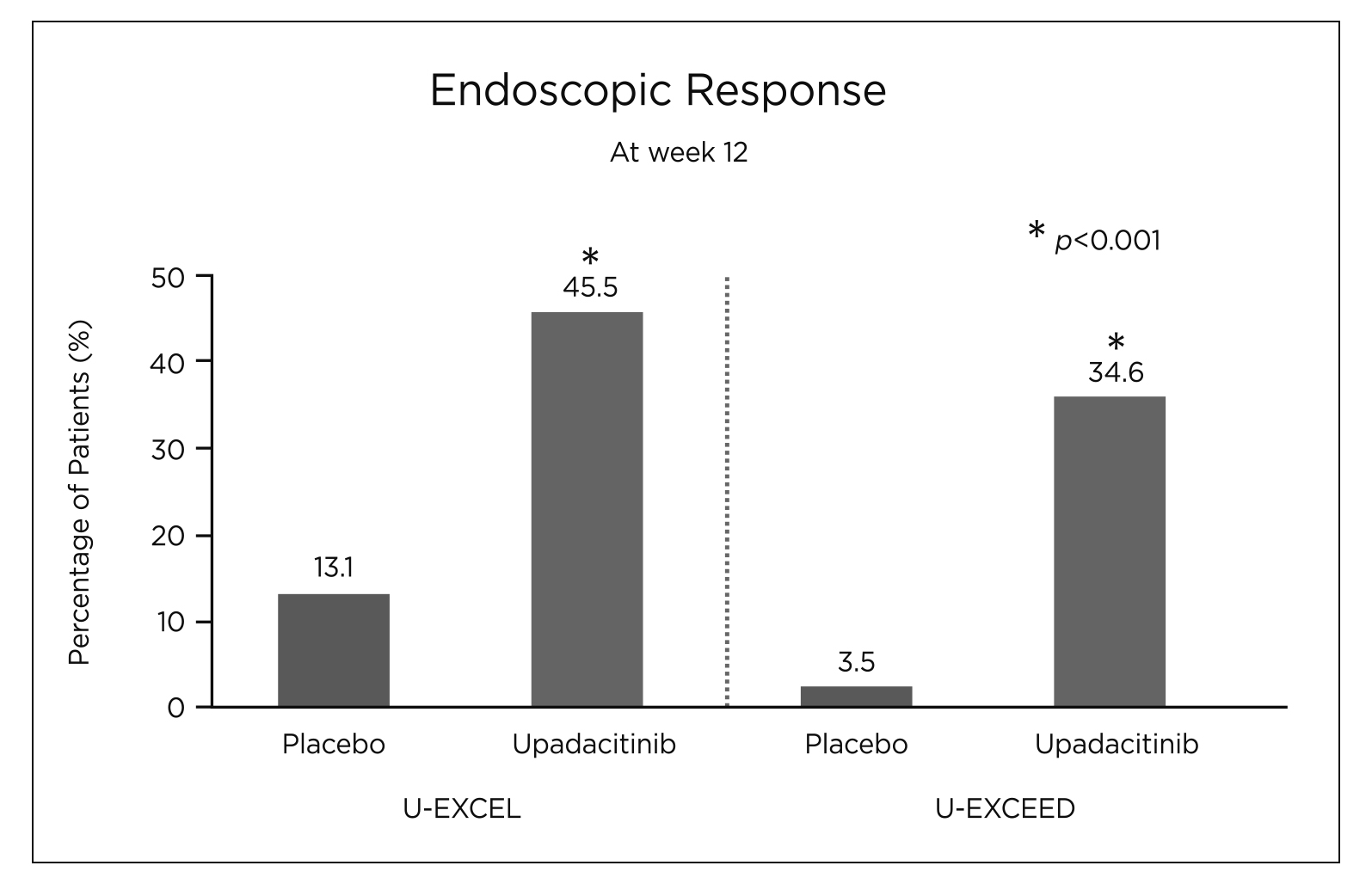

Its effectiveness and tolerability as an induction and maintenance therapy for CD had been substantiated in a number of clinical trials and real-world studies11–14. The efficacy and safety of upadacitinib were evaluated in the U-EXCEL and U-EXCEED phase 3 induction trials that involved 526 and 495 adult patients with moderate-to-severe CD for at least 3 months respectively14. It was found that a significantly higher percentage of CD patients receiving 45 mg upadacitinib achieved clinical remission (CR) compared to those receiving placebo (49.5% versus [vs] 29.1%, p<0.001 in U-EXCEL and 38.9% vs 21.1%, p<0.001 in U-EXCEED) (Figure 3)14. Similarly, a significantly higher endoscopic response (45.5% vs 13.1% in U-EXCEL and 34.6% vs 3.5%, p<0.001 for all comparisons) was reported in the upadacitinib group compared to the placebo group (Figure 4)14. Besides, patients who had a clinical response to upadacitinib induction therapy were also randomly assigned to the U-ENDURE maintenance trial to receive placebo, 15 mg or 30 mg of upadacitinib once daily for 52 weeks to further evaluate the effects of upadacitinib as maintenance treatment14. The U-ENDURE study included 502 patients, similarly, a significantly higher percentage of CR and endoscopic response was reported in CD patients receiving 15 mg (37.3% and 27.6%, p<0.001), and 30 mg upadacitinib (47.6% and 40.1%, p<0.001) compared to placebo (15.1% and 7.3%, p<0.001)14. This further supports the notion that upadacitinib was superior over placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe CD as an induction and maintenance agent14. Although adverse events associated with JAK inhibition such as opportunistic infections, anaemia, neutropenia and creatine kinase elevation were observed more frequently in CD patients receiving upadacitinib than those receiving placebo, similar rates of serious infections were reported across trial groups (6.1 events per 100 person-years for 15 mg upadacitinib, 7.8 events per 100 person-years for 30 mg upadacitinib and 8.4 per 100 person-years for placebo) in U-ENDURE; this suggests a favourable benefit-to-risk profile of upadacitinib14,15.

Figure 3. Percentage of patients achieving clinical remission (CR) at week 12 in U-EXCEL and U-EXCEED14

Figure 3. Percentage of patients achieving clinical remission (CR) at week 12 in U-EXCEL and U-EXCEED14

Figure 4. Percentage of patients achieving endoscopic response at week 12 in U-EXCEL and U-EXCEED14

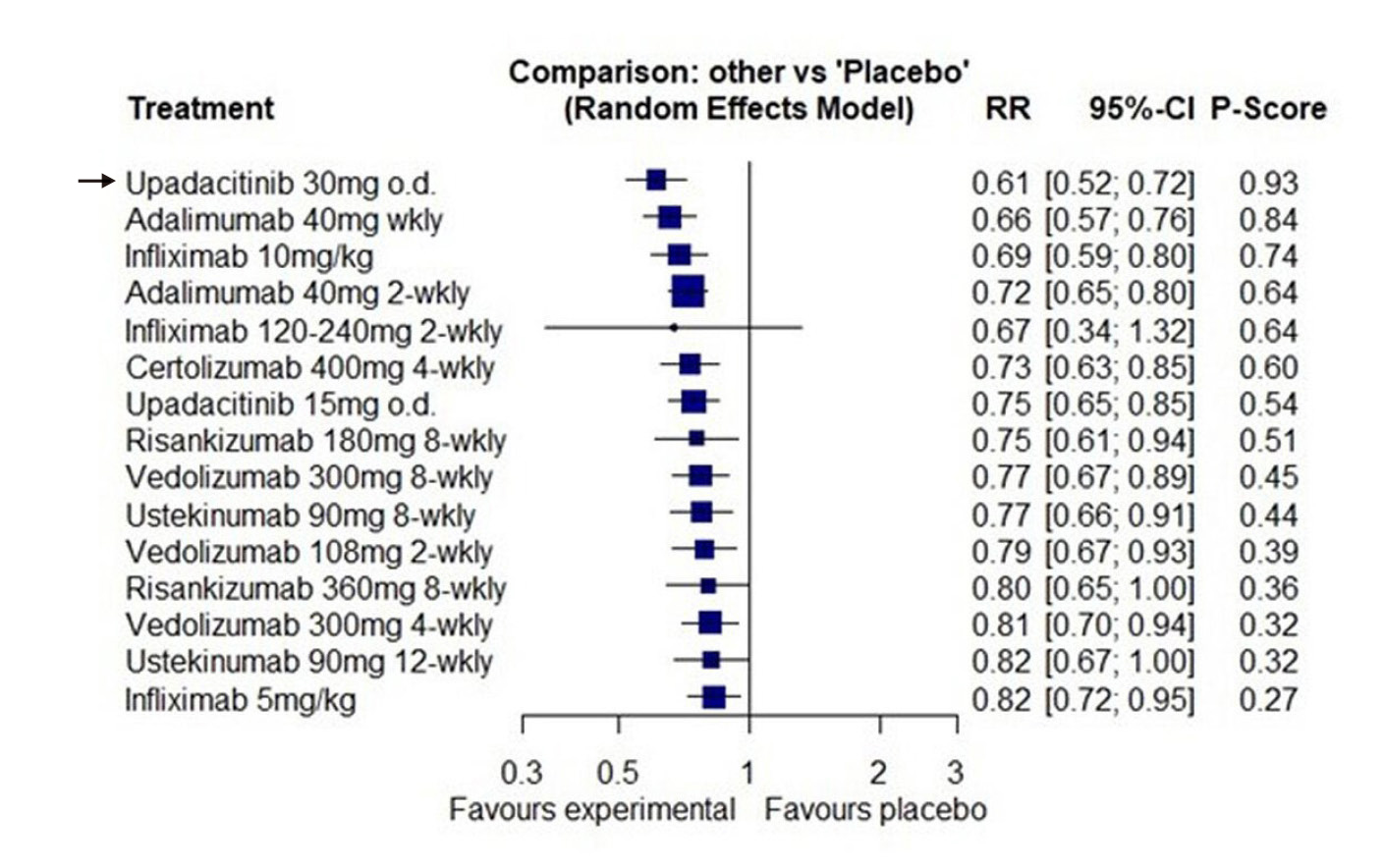

In comparison to other anti-CD therapies, a network meta-analysis (NMA) was conducted to compare the efficacy of 12 biological therapies and small molecules licensed for CD16. The NMA included 25 trials involving 8,720 patients, and concluded that upadacitinib 45 mg was among the top 3 in the induction of CR in CD patients (Relative Risk [RR]= 0.75, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.83, p-score= 0.77)16. Additionally, upadacitinib 30 mg once daily even ranked first for maintaining CR (RR= 0.61, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.72, p-score= 0.93) (Figure 5), further emphasising its promising effect in CD patients.

Figure 5. Forest plot for failure to maintain clinical remission in all re-randomised patients with CD16 (RR= Relative risk of relapse of disease activity, CI= Confidence Interval)

After receiving the FDA approval for the treatment of moderately to severely active CD, growing real-world evidence has further supported the rapid efficacy of upadacitinib13,17–20. Recently, a prospective analysis of clinical outcomes on upadacitinib in CD patients was conducted using predetermined intervals at weeks 0, 2, 4, and 8 to assess the real-world effectiveness and safety of upadacitinib13. Data from 24 CD patients were available at week 2, of whom 16 CD patients had clinically active disease at baseline13. Among them, 50% (8 of 16 CD patients) had a clinical response and 56.2% (9 of 16 CD patients) achieved CR after upadacitinib treatment at week 213. At week 4, an even higher proportion of CD patients, specifically 77.8% (14 of 18 CD patients), demonstrated a clinical response and 63.2% of patients (12 of 19 CD patients) achieved CR among the 27 available data13. Meanwhile, the follow-up safety data including 105 CD patients reported 32.4% of AEs, with acne (22.9%) being the most common AE, followed by nausea (2.9%) and headaches (1.9%) in CD patients receiving upadacitinib treatment13. Thus, the efficacy and safety of upadacitinib remain conclusive in patients with moderate-to-severe active CD. In conclusion, upadacitinib offers a new, rapid, robust, and safe treatment option for CD patients who are desperate to get on with their social lives.

Abbreviations

AE= Adverse Event, CD= Crohn’s Disease, CI= Confidence Interval, CR= Clinical Remission, FDA= U.S. Food and Drug Administration, GI= Gastrointestinal, IBD= Inflammatory Bowel Disease, IBS= Irritable Bowel Syndrome, IL= Interleukin, IFN-γ= Interferon Gamma, JAK= Janus Kinase, NMA= Network meta-analysis, RR= Relative Risk, TNF= Tumour Necrosis Factor

References

1. Baumgart DC & Sandborn WJ. The Lancet. 2012;380(9853):1590-1605. 2. Mak JWY et al. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2021;15(3):401-408. 3. Cho CW et al. Gut Liver. 2022;16(2):157-170. 4. Ha F & Khalil H. Crohn’s disease: a clinical update. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2015;8(6):352-359. 5. Ng SC et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):158-165.e2. 6. Cushing K & Higgins PDR. JAMA. 2021;325(1):69. 7. Kumar A et al. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2022;15:17562848221078456. 8. Schoepfer AM et al. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108(11):1744-1753. 9. Scheurlen KM et al. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023;12(17):5595. 10. Schoefs E et al. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2023;17(3):379-388. 11. Herrera-deGuise C et al. Frontiers in Medicine. 2023;10. 12. Sandborn WJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(8):2123-2138.e8. 13. Friedberg S et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2023;21(7):1913-1923.e2. 14. Loftus EV et al. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(21):1966-1980. 15. Traboulsi C et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68(2):385-388. 16. Barberio B et al. Gut. 2023;72(2):264-274. 17. García MJ et al. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2024;18(Supplement_1):i1112-i1113. 18. Friedberg S et al. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2023;17(Supplement_1):i931-i933. 19. Kubesch A et al. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2024;18(Supplement_1):i1955-i1955. 20. Liu E et al. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology | ACG. 2023;118(10S):S759.