Early Insight to the Dyslipidaemia Pandemic

Dyslipidaemia is defined as lipid imbalance affecting the low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), elevated triglyceride (TG), high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and elevated total cholesterol (TC)1. The risk factors for dyslipidaemia includes poor diet, smoking, diabetes mellitus (DM), in addition to genetic predisposition (familial hypercholesterolaemia)1. More importantly, dyslipidaemias may lead to cardiovascular disease (CVD)2 as one-third of deaths globally are attributed by the dyslipidaemia-related (elevated LDL-C) CVD3. Furthermore, metabolic risk factors, such as elevated plasma LDL-C is becoming more prevalent in low-income setting due to a change in dietary habits, globally3. Thus, dyslipidaemia has remained a serious public health concern and optimising the treatment for CVD prevention remains a cornerstone. Traditionally, high-risk patients such as those with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) are treated with high-intensity statin based on clinical guidelines4,5. However, substantial patients with T2D and ASCVD may not be able to continue the treatment due to statin-related adverse effects (SRAEs)6. Thus, ezetimibe is often added to reduce LDL-C by at least 23-24%7 and recent studies has favoured the use of moderate-intensity statin with ezetimibe for better LDL-C reduction.

To Go Full Throttle or Not?

Statin is known to reduce LDL-C in those with and without the risk of CVD, however, there is residual risk of recurrent cardiovascular (CV) events and safety concerns associated with high-dose statin therapy; thus lipid modifying agents such as ezetimibe is often added7. This therapeutic efficacy was assessed in IMPROVE-IT study, a double-blinded randomised trial involving 18,144 patients hospitalised for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) within the preceding 10 days with LDL-C levels of 50-100 milligrams per decilitres (mg/dL) (1.3-2.6 millimoles per litres [mmol/L]) if on lipid lowering treatment or 50-125 mg/dL (1.3-3.2 mmol/L) if they were not on treatment7. The study had a median follow-up for 6 years with a primary end point of composite CV death, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), unstable angina requiring rehospitalisation, coronary revascularisation (≥30 days after randomisation) or non-fatal stroke. Results demonstrated that ezetimibe addition to statin therapy lowered the LDL-C by approximately 24% that led to an improved CV outcome7. But should ezetimibe be added to a high-intensity or moderate-intensity statin treatment for an effective outcome?

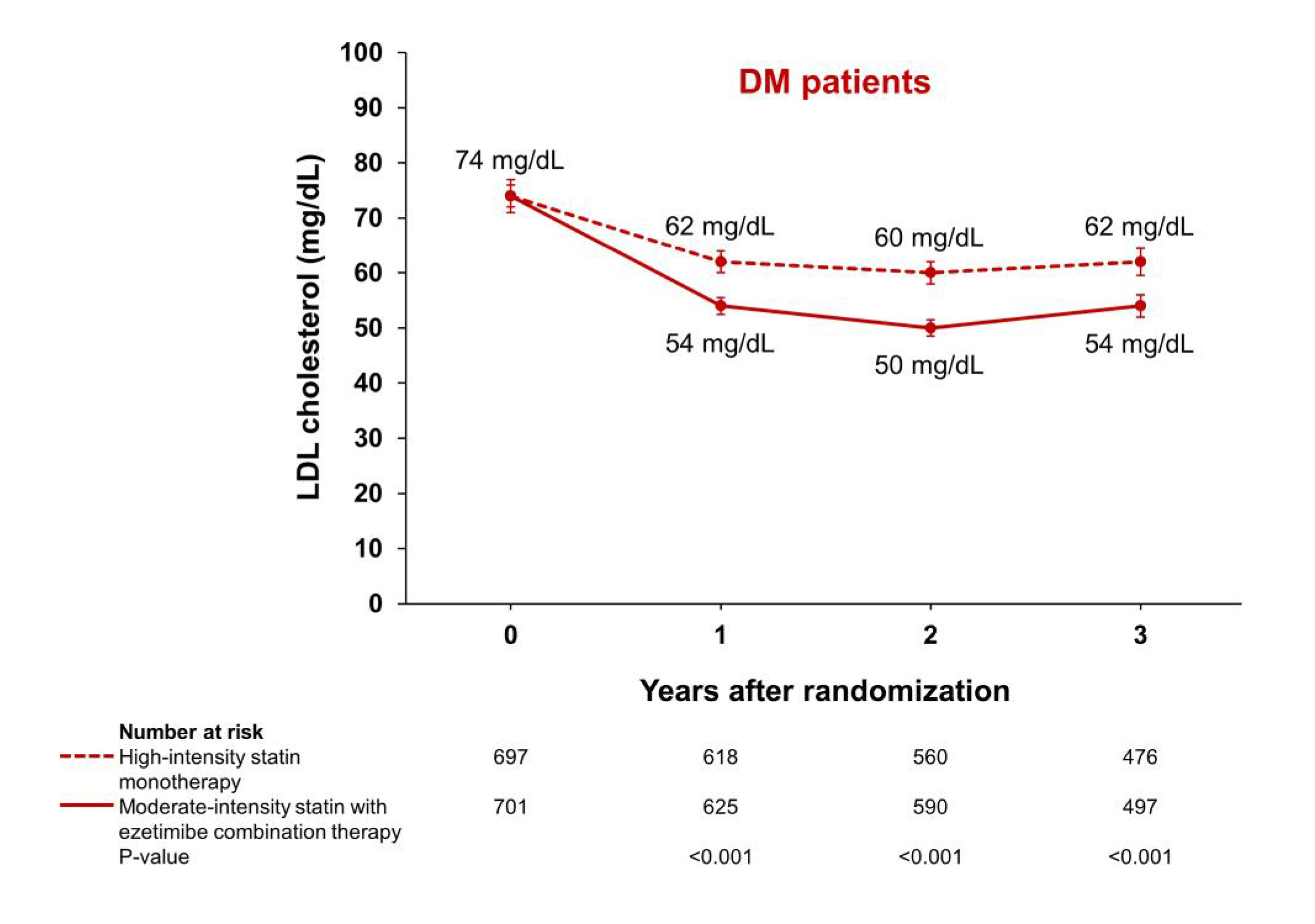

The RACING study was a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial that evaluated the effects of moderate-intensity statin with ezetimibe (ezetimibe combined therapy) against the high-intensity statin monotherapy in patients with DM and ASCVD8. The primary outcome was a 3-year composite of CV death, major cardiovascular events (MACE), or non-fatal stroke. Interestingly, 37% patients were diabetics at baseline and the incidence of primary outcome occurred in 10.0% of DM patients on ezetimibe combined therapy compared to 11.3% on high-intensity statin monotherapy (hazard ratio: 0.89; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.64-1.22; p=0.460). Surprisingly, the intolerance-related discontinuation or dose reduction was higher in high-intensity statin monotherapy group compared to the ezetimibe combination therapy (5.2% vs 8.7%); p=0.014)8. Therapeutically, a consistent LDL-C reduction was seen at year 1, 2, and 3 in ezetimibe group (81.0%, 83.1% and 79.9%, respectively), compared to high-intensity statin group (64.1%, 70.2% and 66.8%, respectively) (Figure 1). These observations suggested that ezetimibe combination therapy is effective and can be used as an alternative to high-intensity statin, particularly in those intolerant to high-statin monotherapy doses or those requiring further reduction in LDL-C with background of DM and ASCVD8 .

Figure 1. LDL cholesterol levels over time among patients with diabetes mellitus. Serial median values for LDL cholesterol among patients with diabetes mellitus. The I bar indicates 95% confidence intervals. Under the graph, P-values for the comparison between the ezetimibe combination therapy group and the high-intensity statin monotherapy group in the LDL cholesterol levels at 1, 2, and 3 years are presented8. DM= diabetes mellitus.

These findings were also substantiated by a post-hoc analysis of the RACING trial performed by Park et al., (2023) assessing the clinical benefit of moderate-intensity statin with ezetimibe in patients following the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) compared to high-intensity statin monotherapy. In addition, among 3,780 patients involved in the study, 2,497 had prior history of PCI and the results indicated that a higher LDL-C reduction was attained with moderate-intensity statin therapy with ezetimibe compared to the high-intensity statin monotherapy regimen. The conclusion drawn from the study suggested ezetimibe combined therapy was effective and the observations were consistent with the RACING trial suggestive of ezetimibe combined treatment was more tolerable in patients who had undergone a PCI9. Similarly, this combination has also shown to have better treatment adherence, lower intolerance-related drug discontinuation compared with better safety in older adults with ASCVD compared to high-intensity statin monotherapy10. In summary, LDL-C reduction is paramount, particularly in those with DM and high CVD risk.

References

1. PPappan N, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2023. 2. Pengpid S, et al. Prev Med Rep 2022; 28: 101874. 3. Pirillo A, et al. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2021; 18(10): 689-700. 4. Arnett DK, et al. Circulation 2019; 140(11): e563-e95. 5. Virani SS, et al. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2023; 82(9): 833-955. 6. Ward NC, et al. Circulation Research 2019; 124(2): 328-50. 7. Cannon CP, et al. New England Journal of Medicine 2015; 372(25): 2387-97. 8. Lee Y-J, et al. European Heart Journal 2022; 44(11): 972-83. 9. Park JI, et al. EClinicalMedicine 2023; 58: 101933. 10. Lee SH, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023; 81(14): 1339-49.