The Hippocratic Oath “to do no harm” highlights the primary moral obligation of physicians to patients and addresses the requirements to act in a professional manner as a medical practitioner. In clinical practice, it is inevitable that therapeutic interventions such as surgeries and chemotherapy may cause harm to patients, but it is often weighed against the benefits perceived by the procedure in order to achieve a greater clinical outcome overall. Contrary to this, medical negligence is a serious global health issue which may potentially result in patient injuries or death. In cases where patient death is attributed by a grossly negligence, the physician involved may be charged with the criminal offence of gross negligence manslaughter (GNM)1. Since negligence is defined as being careless and involuntary; questions arise on whether a physician should be penalised in cases of unexpected patient death even if he/she had no criminal intention from the public interest point of view.

A tort is a civil wrong that causes a claimant to suffer loss or harm, resulting in legal liability for the person who commits the tortious act. Whereas medical negligence is a type of tort with compensatory damages being the usual remedy2. To establish a civil claim in medical negligence, the claimant, who is usually the sufferer, is required to show that the defendant, commonly the physician and/or the organisation, owe him/her a duty of care and the standard of care provided by that physician has fallen below the reasonable standard, i.e., a breach of duty of care. In addition, the claimant is required to prove the harm was caused by the breach of duty, without any intervening event3.

When the duty of care is breached with grossly negligent acts or omissions leading to patient death, the physician in question can be charged of GNM and may be subjected to imprisonment if convicted. Nonetheless, prosecution of physicians for GNM is rare as highlighted by Ferner and McDowell (2006), with only 85 cases of physician charged with GNM reported in the United Kingdom between year 1795 and 2005. Among these, only 22 cases lead to convictions and 3 pleaded guilty4. While “actus reus” (“guilty act”) and “mens rea” (“guilty mind”) are the two essential elements required for a criminal conviction5, in the case of R v Bateman [1925], in which a physician was convicted of manslaughter arising out of his treatment of a woman in childbirth, it was established that a gross level of negligence satisfied the mens rea element6.

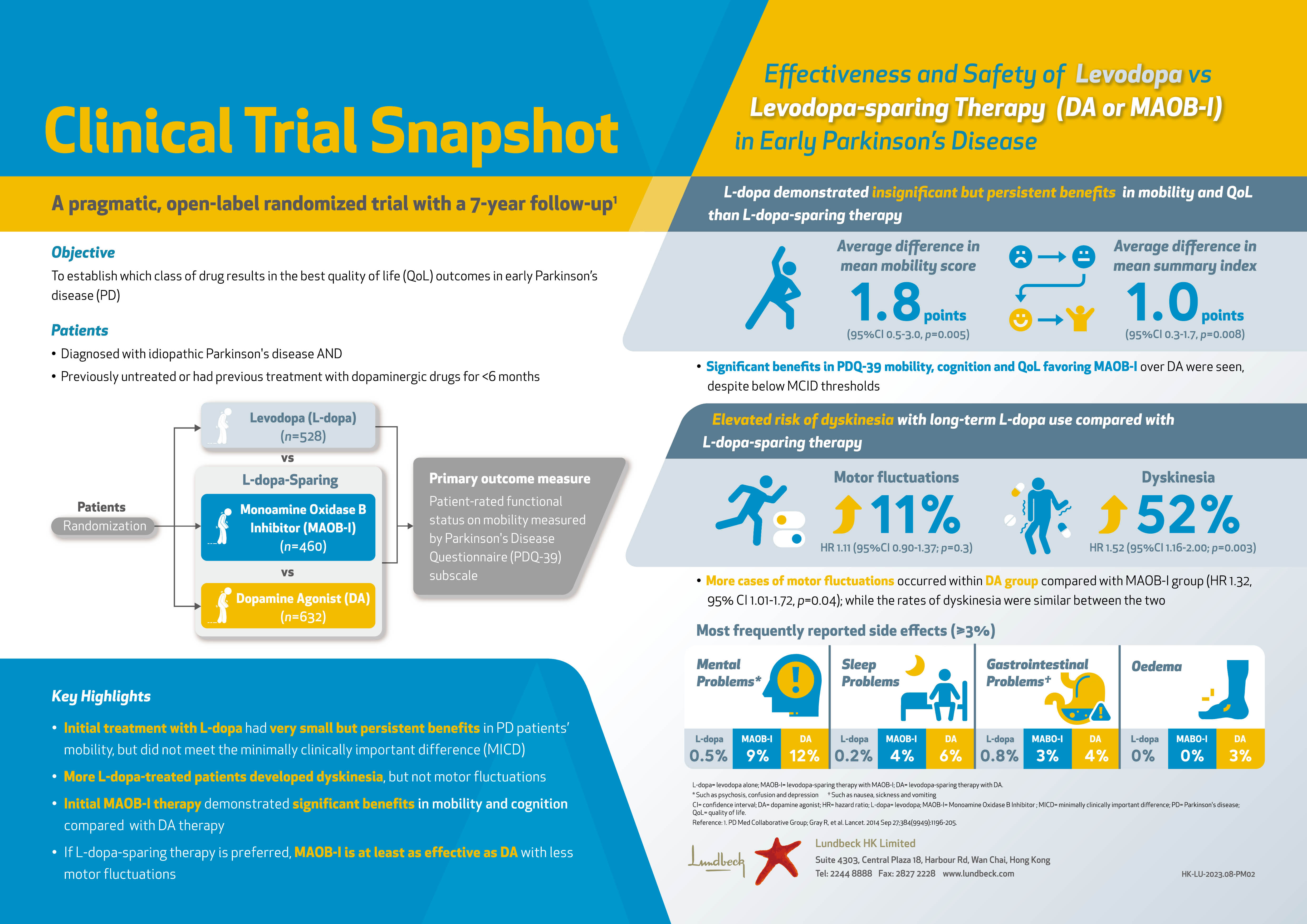

The leading authority on GNM is R v Adomako [1994], in which Dr. Adomako, an anaesthetist who oversaw a patient during an ophthalmic procedure failed to act upon when he noticed the oxygen supply was disconnected for at least 6 minutes which contributed to patient’s death. The Court held that Dr. Adomako's conduct amounted to a gross dereliction of care. Adomako appealed his conviction challenging the basis that a breach of duty should not have amounted to involuntary manslaughter; however, his conviction of GNM was upheld by the House of Lords7. Essentially, a legal test for the conviction of GNM was established in the case (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Adomako test for a conviction of GNM

Of note, the Adomako test focuses on the conduct of an individual with little weight given to systemic factors, such as the responsibilities of the other members of the clinical team. Moreover, as demonstrated in the case of Adomako, the sentencing is also dependent on individual basis. In this regard, the judgement of GNM can be considered as an individualisation of legal liability in medical incidents.

Each GNM case is undoubtedly tragic, nonetheless, the factors leading to GNM should be prevented by learning from these mistakes and prevent recurrences in medical profession. Even though the physician in-charge are considered to be primarily responsible during clinical incidence, he/she should not be solely held responsible when medical negligence is considered. A good example of this was highlighted in the case of Bawa-Garba v GMC [2018] which took place in the United Kingdom and was considered a landmark case of GNM in recent years as it was very controversial among medical professionals and the public. In this case, Dr. Bawa-Garba, a trainee paediatrician at the Leicester Royal Infirmary was found guilty of GNM over the death of Jack Adcock, a 6-year-old child with Trisomy 21 and a heart condition.

Jack was admitted to Leicester Royal Infirmary with sickness and diarrhoea under the care of Dr. Bawa-Garba and 2 other clinical staff. Unfortunately, the patient died later on the same day, and his death was found to have been contributed by a series of errors by the clinical team. Dr. Bawa-Garba and the related nurse, Ms. Amaro, were convicted of GNM, and both handed 2-year suspended prison sentences. Thereafter, Dr. Bawa-Garba was suspended from practice for 12 months followed by erasure from the UK Medical register2.

Of note, apart from the errors associated with the clinical team, various systemic factors were ignored. For instance,

Dr. Bawa-Garba was on her first day back from thirteen months of maternal leave with no induction provided by the national health service (NHS) trust. Moreover, Dr. Bawa-Garba had been on a 13-hour shift without any breaks raised serious safety concerns. Besides, Dr. Bawa-Garba received little to no support from her supervising consultant and there were medical staff shortage with nursing number and skill mix that did not reach nationally recommended standards of safety8.

The case of Dr. Bawa-Garba clearly reflected the complex nature of clinical settings and highlighted the influence of systemic factors that have contributed to this tragedy. Dr. Bawa-Garba was allowed to appeal against the decision made for her erasure from the UK Medical register and eventually won her appeal and was able to return to hear clinical duties in 2018.

Focusing back to the local scenario, the HKSAR v Chow Heung-Wing, Stephen and 2 others ("DR Group") [2015] case was one of the worst medical incidents recorded in Hong Kong. In this case, a 31-year-old female received a transfusion of cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells for their alleged anti-ageing effects at a beauty clinic run by the DR Group. Essentially, the treatment had no scientific backing regarding its efficacy and safety.

After the administration of CIK treatment, the patient developed symptoms of septicaemia and died of multi-organ failure. Of note, the blood products that were administered into the deceased patient was later found to be contaminated with Mycobacterium abscessus, which was also found on the equipment at the DR Group clinic laboratory. The laboratory technician admitted his failure to screen for the bacteria during preparation of the transfusion blood product. Dr. Chow Heung-Wing, the owner of the clinic, and the related laboratory technician were convicted of manslaughter by gross negligence and sentenced to 12 and 10 years, respectively1.

Besides, Dr. Mak Wan-Ling, the doctor who administered the blood products was also charged with manslaughter by gross negligence. However, the jurors were unable to reach a verdict. After the re-trial, Dr. Mak was convicted and sentenced to 3.5 years in prison even though she claimed that she was unaware that bacteriological tests had not been carried out on the blood products prior to administration to the patient. In 2022, she appealed against her conviction, which was dismissed by the Court of Appeal9.

In the judgment of Dr. Chow and the technician’s appeal against the convictions and sentences, the Court held that this case was a classic case of negligence under established principles. The focus of this case had been on the failure to establish a safe system to protect the sterility and integrity of the blood product. The appeal against their convictions was dismissed10.

In considering the cases of Dr. Bawa-Garba and DR Group, the issues of involuntary error and conscious violation were highlighted. In a clinical setting, even the most capable individuals may commit errors, particularly in the complex situations. By nature, human errors are unintentional. Therefore, taking the systemic factors into account, Dr. Bawa-Garba’s case can be considered as involuntary errors which were neither intentional, nor pre-meditated, hence her appeal was approved. In contrast, violations are associated with deliberate disregard for patient safety and unjustified risk taking at patient’s expense. Obviously, Dr. Chow in DR Group case was well aware that the efficacy and safety of CIK treatment was not established, nonetheless, he deliberately went ahead with the treatment without informing the patient regarding the treatment efficacy and associated risks. Thus, this amounts a conscious violation and should be considered as a criminal offence.

There are suggestions advocating a stringent standard for criminalising clinicians charged with GNM in order to protect patient safety and ensure the standard of medical professionals being maintained. Nonetheless, simply penalising those who committed unintentional errors will not prevent mistakes from happening in clinical practice. Continuous professional training and optimising the working conditions are required to strengthen the skills and improve the morale of clinicians. In conclusion, sentencing clinicians to prison for causing death through involuntary errors may not be fair, especially if they have done their best utilising the resources available to them. Contrary to this, deliberate violations of the established rules and standards truly deserve punishment.

References

1. Leung. Hong Kong Medical Journal 2018; 24: 384–90. 2. Cheluvappa et al. Annals of Medicine and Surgery 2020; 57: 205. 3. Connelly et al. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine 2020; 21: 524. 4. Ferner et al. J R Soc Med 2006; 99: 309–14. 5. Beattey et al. Behavioral sciences & the law 2018; 36: 457–69. 6. Robson et al. Journal of Criminal Law 2020; 84: 312–40. 7. R v Adomako [1994] UKHL 6 (30 June 1994). 8. Case et al. Med Law Int 2020; 20: 58–72. 9. HKSAR v MAK WAN LING [2022] HKCA 387. 10. HKSAR v CHOW HEUNG WING, STEPHEN AND CHAN KWUN CHUNG [2021] HKCA 1655.