Specialist in Infectious Disease

MBBS(HK), FRCP (Lond),

FRCP (Edin), FFPH (UK),

FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine),

MPH (Johns Hopkins) MSc Infect Disease LSTMH (Lond),

Dip G-U M (LAS), DTM&H (Lond), PGDipClinDermat (QMUL)

Honorary Consultant, Infectious Disease Centre & Department of Medicine & Geriatrics,

Ureaplasma Urealyticum/

Ureaplasma Parvum (UU/UP):

An Emerging Resistant Pathogen with Potential Severe Consequences

Ureaplasma spp. are some of the smallest self-replicating, free-living micro-organisms and there are two species, namely Ureaplasma urealyticum (UU) and Ureaplasma parvum (UP) which can only be distinguished by molecular tests such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR). UP is more common as a pathogen clinically but UU is a more pathogenic among male with urethritis1. Transmission is through genital-to-genital or oral-to-genital contact, from mother to baby or rarely through transplanted tissues. The increasingly more widespread availability of molecular tests for UU/UP results in more people being diagnosed as having this organism. I have recently seen a number of female patients with persistent Ureaplasma found in urine despite more than two courses of first line antibiotics. I have also seen a number of male patients with Ureaplasma associated urethritis and prostatitis which were difficult to clear.

Is It a True Pathogen?

Ureaplasma can live in the mucosa of urogenital tract of healthy adults without causing any symptoms. It was found that up to 80% of sexually mature female have Ureaplasma spp. in their genital tract2. It was found in 5 to 15% of healthy males aged 16 to 44 years old3. Such high prevalence in asymptomatic adults makes people question the pathologic role of Ureaplasma in causation of disease. Hence, Ureaplasma infection is often not classed as a sexually transmitted infection.

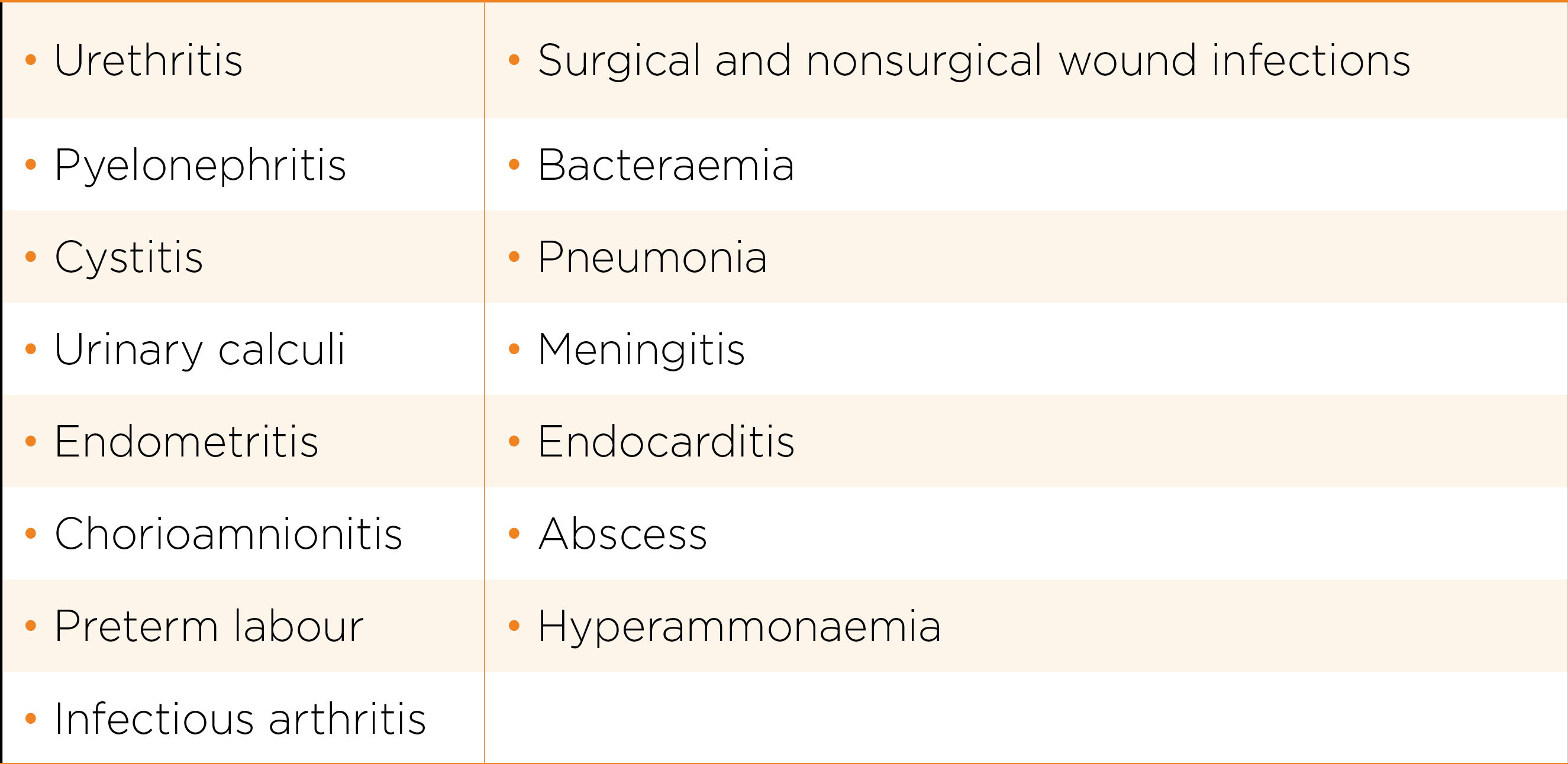

For female, Ureaplasma infection are implicated in endometritis, and bacterial vaginosis. Ureaplasma infection has been associated with adverse outcomes in pregnancy by causing chorioamnionitis and premature rupture of membrane4.

For male, it is one of the causative agents of non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU) with UU as the more common species5. UU may be responsible for approximately 3 to 11 percent of NGU cases6. UP can also cause NGU, particularly when present in high numbers7. It is also implicated in chronic prostatitis.

There is also emerging evidence that UU may be associated with infertility in men8. In one study, 12% of infertile men were found to be Ureaplasma PCR positive, compared to 3% of fertile men9. Men with Ureaplasma were found to have significantly lower concentrations of sperm cells, lower volumes of seminal fluid and higher abnormal sperm morphology. The role of UU can be highlighted by frequency of 9% in infertile men compared with 1% in healthy controls. A systematic review found significant relationship between UU infection and male infertility10.

There were reports of disseminated infections in immunocompromised hosts such as those with antibody deficiencies, either congenital or acquired (e.g. Anti-CD20 therapy)11,12 and hyperammonaemia in transplant recipients13.

Emergence of Resistance

Ureaplasma spp. are intrinsically resistant to beta- lactam and glycopeptide antibiotics due to lack of a cell wall. Apart from that, sulphonamide, trimethoprim, nalidixic acid and rifampicin are not efficacious against the organism. Antibiotics belonging to the tetracycline, macrolide, fluoroquinolone classes are found to have activity against Ureaplasma spp.

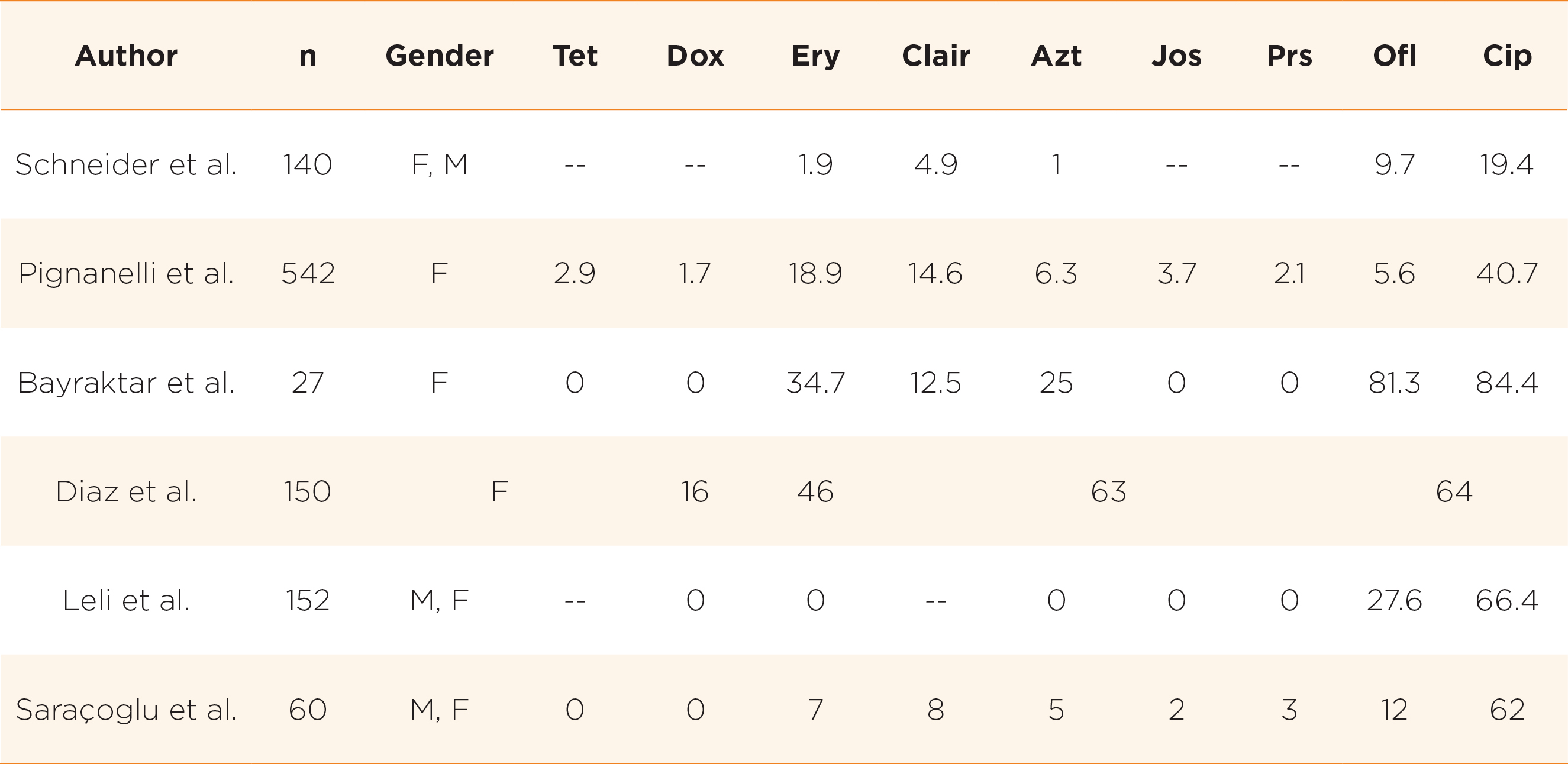

However, in recent years, there is global trend towards resistance to the commonly used antimicrobials and a rising trend is observed especially in developing countries14. For example, among non-pregnant women in South Korea, it was found that only 6% and 18.7% of Ureaplasma spp. isolates were susceptible to ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin respectively15. In China, only 47% and 12% of strains are susceptible to ofloxacin and levofloxacin respectively10. High rates of resistance to tetracyclines were noted in South Africa (only 27% susceptible)16, USA and Cuba (only 60-70% susceptible)17,18. In developing countries where there are more excessive usage of antibiotics, there was increasing trend of multidrug resistance (MDR) development, defined as presence of resistance to at least one agent in three or more antibiotic classes14. There is geographical variation in resistance pattern globally reflecting the variation in antibiotic usage pattern19. For example, in a study from Tunisia, 37.6% of strains were multidrug resistant, out of which 60.7% of UU and 28.8% of UP were MDR20. Table 1 shows the antibiotic resistance rates as obtained in various studies.

Some Tips for Treatment

Ureaplasma spp. may be present simultaneously with other pathogens in many of the below conditions. The role that Ureaplasma spp. play is often minor and hence decision to treat should reflect the possibility. Facing with a positive test, the clinician will have to make decision on whether the pathogen is significant and hence need treatment. These conditions include:

There are no universal guidelines for the treatment of Ureaplasma infection. The drugs of choice for Ureaplasma infections include macrolides, tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones. High level resistance to erythromycin is uncommon. For urethritis caused by Ureaplasma species, azithromycin and doxycycline are used with good efficacy of 75% and 69% respectively22,23. However, with the global emergence of resistance, unsuccessful treatment will become more common. For non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU) in men which is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis in 20-50% and Mycoplasma genitalium (M. genitalium) in 10-30% of cases, doxycycline should be used as first line as it has a higher cure rate in C. trachomatis than azithromycin22, and it cures 20-40 % of M. genitalium without inducing macrolide resistance. Azithromycin has been widely used as a first line treatment for NGU, but it may have contributed to the increasing M. genitalium resistance24. Fluoroquinolones are useful alternatives for treatment as activity of quinolones is not affected by tetracycline resistance. Fluoroquinolones usually occurs in patients with prior exposure to the drugs. For pregnant women, macrolides such as erythromycin are often used because tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones are contraindicated. For severe infections, it is recommended to use agents from 2 different classes to increase the likelihood of therapeutic success25. For particularly resistant infections refractory to antimicrobial therapy, one may require more prolonged duration of combination of antibiotics preferably with guidance of antibiotic resistance testing. One should also note that macrolides and fluoroquinolones may prolong QT interval and one should be cautious of this potential side effect especially in people who are already on medications that prolong QT interval.

Treatment of sexual contact(s) is recommended in case treatment of index case is needed. Use of condom or sexual abstinence is recommended until both parties are clear of the infection as practiced in management of other sexually transmitted infections. Treatment success should be tested at least 3 weeks post-treatment.

Take Home Messages

References

1. Zhang et al. PLoS One 2014; 9: e113771. 2. Taylor-Robinson et al. Res Microbiol 2017; 168: 875-81. 3. Horner et al. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol 2018; 32: 1845-51. 4. Sweeney et al. Clin Microbiol Rev 2017; 30: 349-79. 5. Wetmore et al. J Infect Dis 2011; 204: 1274-82. 6. Couldwell et al Sydney men. Int J STD AIDS 2010; 21: 337-41. 7. Deguchi et al. Int J STD AIDS 2015; 26: 1035-9. 8. Zhu et al. Exp Ther Med 2016; 12: 1165-70. 9. Zeighami et al. Int J STD AIDS 2009; 20: 387-90. 10. Huang et al. World J Urol 2016; 34: 1039-44. 11. Furr et al. Ann Rheum Dis 1994; 53: 183-7. 12. Jhaveri et al. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6. DOI:10.1093/ofid/ofz399. 13. Bharat et al. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7: 284ra59. 14. Song et al. J Clin Pathol 2014; 67: 817-20. 15. Lee et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020; 64. DOI:10.1128/AAC.01065-20. 16. Redelinghuys et al. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14: 171. 17. Li et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56: 2780-3. 18. Díaz et al. MEDICC Rev 2013; 15: 45-7. 19. Yang et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020; 64. DOI:10.1128/AAC.02560-19. 20. Boujemaa et al. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2020; 9: 19. 21. Saracoglu et al. J Urol Surg 2018; 5: 17-21. 22. Manhart et al. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56: 934-42. 23. Khosropour et al. Sex Transm Infect 2014; 90: 3-7. 24. Moi et al. BMC Infect Dis 2015; 15: 294. 25. Luo et al. Chemotherapy 2011; 57: 128-33.