The Role of Spiritual Care in Mental Well-being of Healthcare Professionals during COVID-19 Pandemic

Subjective well-being concerns one’s evaluations of the quality of his/her own lives. This appraisal comprises cognitive judgments about achieving important values and goals in the life span of the individual and the balance between positive and negative effects1. In the literature, the roles of spirituality and religiosity play in one’s self-perceived well-being have been investigated and a positive effect of spirituality and religiosity on many psychosocial and health-related outcomes across the lifespan has been identified2. The current COVID-19 pandemic has posed a challenge to all governments and health institutions because of its impact in different areas of life such as political, socioeconomic and health management. Particularly, the mental distress experienced by healthcare professionals (HCPs) is substantial3. In view of the potential positive impacts of spirituality and religiosity on mental well-being, the roles of spiritual-religious coping strategies in optimising mental well-being of HCPs in public health crisis are noteworthy.

Perceived Mental Stress among HCPs during COVID-19 Pandemic

At the frontline of the battlefield during COVID-19 pandemic, HCPs are taking the risk to be infected and thus they are considered as one of the most vulnerable categories to develop psychological stress and other mental health symptoms. Practically, while social distancing and work-from-home policies are recommended in various countries or regions, HCPs are continuing to work in their respective areas with an overwhelming workload. In addition to having physical exhaustion, they are suffered from substantial mental health impact due to the loss of the infected patients, personal safety, and the concern of passing infections to family members4.

Recently, Htay et al (2020) conducted a web-based survey investigating the mental health impact of COVID-19 among HCPs. 2,097 HCPs from various professions such as medical doctors, nurses, midwives, medical assistants and laboratory technicians in either government or private sectors in 31 countries were involved in the study. Notably, the study especially focused in the low- and middle-income countries such as Kenya, Mozambique, Myanmar and Philippines, where the healthcare systems had limited resources to tackle the current pandemic, and mental health support was sparse. The results indicated that the prevalence of anxiety was 60% and depression was 53%. Although the symptoms were mainly mild or moderate, only 1 out of 4 respondents reported the availability of mental health support at their workplaces3.

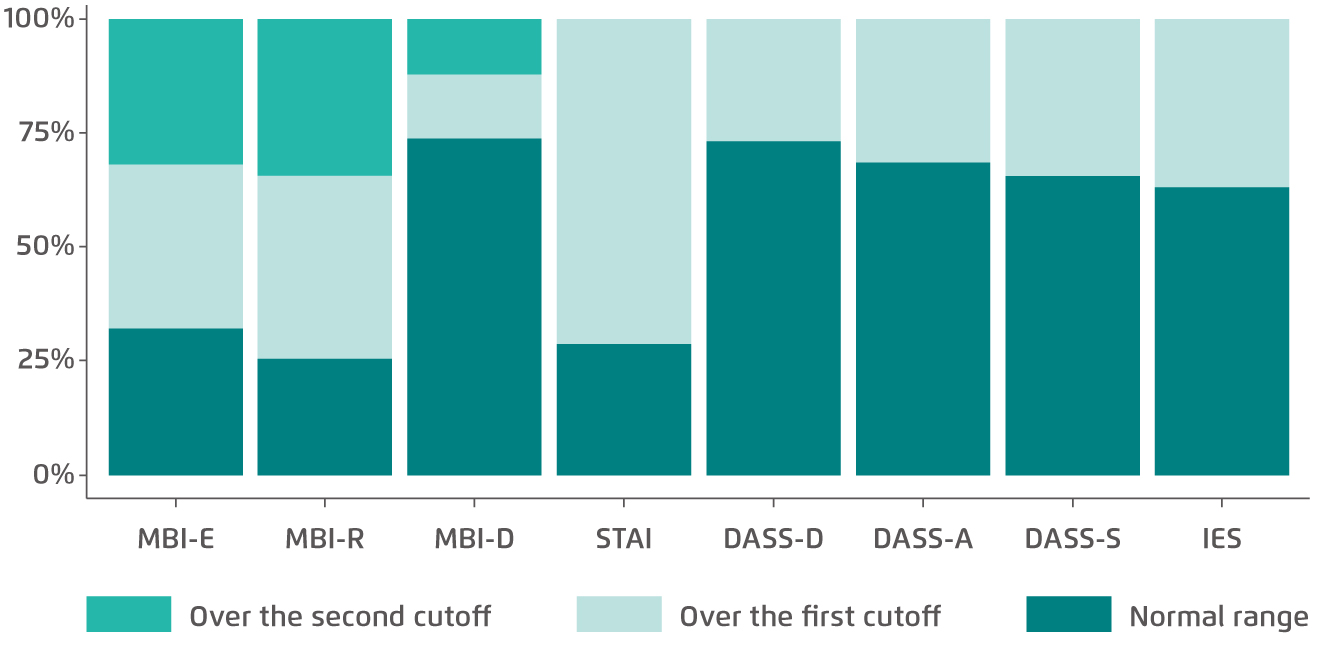

The cross-sectional study by Giusti et al (2020) provides a detailed description on the burnout and psychopathological conditions in HCPs during the current pandemic. There were totally 330 HCPs in a health institution in the Northern Italy recruited in the online survey. Among them, 71.2% reported scores of state anxiety above the clinical cutoff, whereas 26.8% had clinical levels of depression, 31.3% had anxiety, 34.3% had stress and 36.7% had post-traumatic stress. Moreover, 31.9% of participants reported severe level of emotional exhaustion (Figure 1)5. Hence, previous data reflected that HCPs are suffering both significant physical exhaustion and mental distress during the current pandemic, whereas monitoring and timely support are urgently needed.

Figure 1. Prevalence of burnout and psychopathological symptoms among HCPs5

MBI-E: Maslach Burnout Inventory-Emotional Exhaustion; MBI-R: Maslach Burnout Inventory-Reduced personal accomplishment; MBI-D: Maslach Burnout Inventory-Depersonalisation; STAI: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; DASS-D: Depression Anxiety Stress Scales 21-Depression; DASS-A: Depression Anxiety Stress Scales 21-Anxiety; DASS-S: Depression Anxiety Stress Scales 21-Stress; IES: Impact of Event Scale-6

Spirituality and Mental Well-being

Nowadays, the biopsychosocial model has become more widely accepted as a framework for understanding the needs of patients and their families as compared to the traditional pathophysiological and biological/disease-process approach. In the biopsychosocial model, illness is viewed within the context of the complex interplay of biological, social, psychological and spiritual factors that frame one’s response6,7. In particular, spirituality, religion and culture serve as key components to build the framework by which patients guide decision making during illness and at the end of life.

In the Coping with Cancer study, factors associated with advanced cancer patient and caregiver well-being were investigated. Among 230 patients diagnosed with advanced cancer and with prognosis of less than 1 year, 68% considered religion as very important and 20% rated religion as somewhat important. Of note, private religious/spiritual activities such as prayer and meditation were performed daily by 47% of the patients before their diagnosis and was increased significantly to 61% after the diagnosis (p < 0.0001)8. The findings revealed the importance of spirituality and religion to patients struggling with advanced illnesses.

In patients with chronic diseases, Lynch et al (2012) demonstrated that diabetic patients with greater spirituality, represented by the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale, were associated with less depression, estimated by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale9. This suggested that incorporating spiritual values and beliefs might facilitate treatment of depression symptoms for diabetic patients. Besides, a study on 215 American rural elderly by Yoon and Lee (2004) showed that spirituality and religiosity were significantly associated with positive subjective well-being. Hence, the study commented that religious and spiritual support should be provided by health providers, social workers, and faith communities in order to enhance life satisfaction and lessen emotional distress for the elderly10. Summarising the observations in previous studies, spirituality and religiosity may be a key component for patients to cope with their diseases protecting them against depression and associated with better mental well-being.

Optimising Mental Well-being of HCPs

Spirituality and religiosity have been reported to be effective coping strategies for perceived mental distress especially in stressful times. In a correlational study by Mahamid and Bdier (2020) investigating the relationship between positive religious coping, perceived stress and depressive symptoms in response to the emergence of COVID-19, negative correlation was observed between depressive symptoms and positive religious coping (Pearson’s correlation, r = -0.17, p < 0.01). The results also indicated a negative correlation between perceived stress and positive religious coping (Pearson’s correlation, r = -0.15, p < 0.01)11. Thus, the role of spiritual-religious coping in optimising mental well-being for HCPs during the COVID-19 pandemic is worth considering.

Nonetheless, an important issue is how spiritual-religious coping can be implemented in clinical setting. Chang and Lo (2013) demonstrated that long-term practitioners of meditation exhibited a continuously high degree of cardiorespiratory phase synchronisation, even during rapid breathing, whereas meditation was found to be associated with positive emotions12. Furthermore, respiratory relaxation can reduce anxiety13, help to recover physical equilibrium, and influence the immune response14. On the other hand, music has been reported to increase parasympathetic nervous system activity and provoke a drop in the heart rate, blood pressure and, consequently, in cardiac output and oxygen saturation15. Moreover, Garssen et al (2013) revealed that stress management training consisting relaxation, guided imagery techniques, and counseling yielded less fatigue and sleep problems and was effective in reducing depression in post-operative breast cancer patients16. Therefore, meditation, relaxation, listening to music, and guided imagery are the interventions considered appropriate for spiritual support and are listed in the Nursing Interventions Classification17.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, frontline HCPs have been at high risk of stress, depression and anxiety disorders in addition to physical exhaustion. Therefore, mental health support for HCPs have to be available and accessible, especially for those who are staying alone, single, working in intensive care unit, and those who have a shorter duration of working experience in their professions. In particular, regular monitoring of the health status of HCPs, including mental health conditions, and timely treatment for those in need are essential. As spirituality and religiosity have been demonstrated to enhance mental well-being during stressful moments, incorporating spiritual-religious coping strategies in mental health support for HCPs can be considered. Nonetheless, the factor of cultural background has to be taken into account. Besides, several strategies could be implemented during and after the emergency to support HCPs working with COVID-19 patients, which include incorporating work-hour regulation programs and planning official and unofficial rewards. Last but not least, with the recent launching of vaccines against COVID-19, we hope the pandemic will be over soon. Thanks to all healthcare professionals for your sacrifice and great effort during the stressful time.

References

1. Luhmann et al. J Res Pers 2012; 46: 431-41. 2. Villani et al. Front Psychol 2019; 10: 1525. 3. Htay et al. J Glob Health 2020; 10: 020381. 4. COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet.2020; 395: 922. 5. Giusti et al. Front Psychol 2020; 11: 1684. 6. Engel. Am J Psychiatry 1980; 137: 535-44. 7. Steinhauser et al. J Am Med Assoc 2000; 284: 2476-82. 8. Balboni et al. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 555-60. 9. Lynch et al. Diabetes Educ 2012; 38: 427-35. 10. Yoon and Lee. J Hum Behav Soc Environ 2004; 10: 191-211. 11. Mahamid and Bdier. J Relig Health 2021. DOI:10.1007/s10943-020-01121-5. 12. Chang and Lo. Rejuvenation Res 2013; 16: 115-23. 13. DeZeni et al. Rev Psiquiatr do Rio Gd do Sul 2009; 31: 116-9. 14. Kang et al. Oncol Nurs Forum 2011; 38. DOI:10.1188/11.ONF.E240-E252. 15. Nobre et al. Rev. Neurociencias.2012; 20: 625-33. 16. Garssen et al. Psychooncology 2013; 22: 572-80. 17. Guilherme et al. Religions 2016; 7: 26.