Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) has been a growing health risk concern which manifests as a complex spectrum of ill health symptoms among building occupants. For instance, while urban people spend most of their time indoors, there is a growing social and economic importance of maintaining good indoor air quality1. Notably, the suboptimal indoor air quality in hospitals may increase the risk of infectious disease outbreaks or other diseases related to the physical environment2. Hence, hospital staff are vulnerable to SBS by virtue of the exposure to various chemical, biological and environmental risk factors and strategies alleviating the health impacts of SBS in hospitals and healthcare facilities should be implemented.

SBS in Healthcare Facilities

The physical setting in hospital is one the most complex and challenging indoor environments, where hospital staff are exposed to chemical and biological contaminants from medical drugs, detergents, disinfectants, solvents and various workplace physical factors, including unpleasant odor and dust, noise, temperature, humidity and inadequate light and ventilation2,3,4. These risk factors would trigger SBS, which is defined as the medical condition where people in a building suffer from symptoms of illness or feel unwell for no apparent reason5.

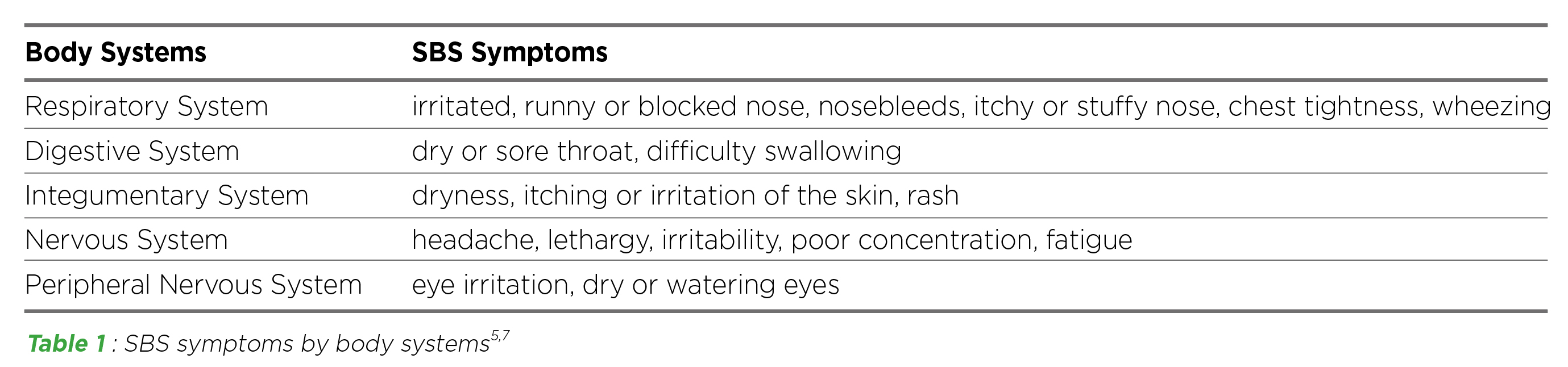

Of importance, SBS is associated with a range of non-specific symptoms involving different body systems, particularly respiratory symptoms2. In a hospital, the most commonly reported SBS symptoms include headache, fatigue, general muscle and joint pain, burning eyes, watery eyes, dry hands, and dry skin (Table 1)3,6.

Table 1 : SBS symptoms by body systems5,7

SBS as an Unaware Problem

SBS is often masked by other detectable illness4, and the symptoms may seem trivial and be improved or even disappear when people leave the building5. Thus, it is commonly regarded as a minor disease. Though SBS is unlikely to be life-threatening or result in permanent disabilities, it significantly impacts the building occupants and the organisations they work for. Remarkably, SBS often results in lower work performances, higher absenteeism and turnover, and increased healthcare expenses1,4,5.

SBS can occur in different indoor settings and the symptoms appear more often in air-conditioned buildings than naturally ventilated buildings1. Former reports suggested that SBS affects most hospital staff, particularly females and nurses3,6,7, which can be attributed to women stronger sense of smell and their greater perception of health6. A recent study conducted in a Turkish hospital found that female gender, a high level of education and stress, and a poor working environment (i.e. presence of odour, presence fungus and moulds on the wall) were associated with the complaints of SBS among the employees6. Nurses, followed by technicians, physicians and secretaries had the highest complaint score in hospital environment and working conditions6.

SBS is a growing health concern that potentially affects the entire working population, whereas healthcare professionals working in the clinical environment are exposed to a broad but specific spectrum of risk factors for SBS. Thus, considerable and constant attention should be given to prevent the problems and create a safe and pleasant working environment.

SBS-associated Respiratory Diseases

The presence of moulds (fungi), pollen, bacteria and viruses in the moist air is correlated with inflammation of the respiration tract8. Ventilation provides fresh air and remove/dilute pollution5. There is a robust affirmative association between ventilation and respiratory health in building occupants, that the increase of ventilation rates per person can reduce the prevalence of SBS symptoms7.

In a multidisciplinary systematic review on 40 original studies, it is evident that there is a strong association between ventilation and the spread/transmission of measles, tuberculosis, chickenpox, influenza, smallpox and SARS9. Poor ventilated spaces with infected person of COVID-19 is one of the transmission ways of the disease10. Essentially, asthma has been reported to correlate closely with SBS. Inadequate ventilation, chemical and biological contaminants, higher temperature and humidity are common triggers of SBS and asthma8. Increased incidence of asthma attacks is also one of the symptoms of SBS12.

There are over 350 occupational asthmagens, in which healthcare workers are particularly exposed to formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde, latex, methyldopa, penicillin and psyllium12. Healthcare workers may be exposed to these allergens and develop symptoms at work with relief on holidays, but with early diagnosis and treatment, occupational asthma may be reversible7.

Strategies to Combat SBS in Hospitals and Healthcare Facilities

While a wide spectrum of risk factors is associated with the development of SBS, strategies have to be addressed to mitigate the factors concerned effectively. In clinical settings, ventilation, infection control, disinfection strategies and sensible plan for building uses are of great importance.

1. Increase air ventilation

Ventilation plays a vital role in exhausting pollutants of both biological and non-biological agents7. Humidifiers, temperature control units, fans, filters, ventilation ducts and cooling towers should be regularly cleaned13. During lunchtime and other breaks, hospital staff can go outside the building to take a breath of fresh air14.

2. Control the source the air pollutants13

Appropriate furniture should be selected to limit pollutants from volatile organic compounds. Indoor air purification system should also be installed to remove air pollutant. During daily operation, detergents with lower chemical concentration should be used. There should also be regular cleaning and pest control works to reduce dust accumulation and micro-organism growth.

3. Employ ultraviolet (UV) disinfection technologies

UV disinfection technologies is a fast-growing chemical-free technology to disinfect pathogens on surfaces, air and water15. UV sterilization devices for various surfaces, such as doorknobs and personal protective equipment, can be utilized in healthcare facilities16. To disinfect the air, ultraviolet-C (UVC) radiation can be used inside air ducts16. It is considered the safest way to employ UVC radiation and is less likely to cause exposure to skin and eyes16.

4. Careful planning of building uses5

Changing partitioning or adding new equipment such as computers, printers and photocopiers may heavily increase the load of heat and pollution. A higher temperature is unlikely to cause symptoms directly but may stimulate material emissions and the growth of bacteria, fungi and dust mites, which can increase SBS symptoms. When there are significant changes in building uses, hospital staff should discuss with managers and professionals familiar with building problems.

In conclusion, there are certain risk factors of SBS and respiratory diseases in the clinical environment. Though SBS may not be perceived as a major threat to health, it affects the working environment, reduces productivity and lowers satisfaction of healthcare workers. Certain strategies should be specially adapted to provide a safe and favorable working environment.

References

1. Indoor Air Quality Management Group - The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Guidance Notes for the Management of Indoor Air Quality in Offices and Public Places. 2. Keyvani et al. Iran J Heal Sci 2017; 5: 19–24. 3. Vafaeenasab et al. Glob J Health Sci 2015; 7: 253. 4. Quoc et al. Int J Environ Res Public Heal 2020, Vol 17, Page 3635 2020; 17: 3635. 5. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Sick Building Syndrome Symptoms. 6. Sayan et al. Med Lav 2021; 112: 161. 7. Nag. Off Build 2019; 53-103. 8. Seyyed Shamsadin. Arch Asthma, Allergy Immunol 2019; 3: 001–2. 9. Li et al. Indoor Air 2007; 17: 2–18. 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Overview and Infection Prevention and Control Priorities in non-U.S. Healthcare Settings. 2021. 11. Joshi. Indian J Occup Environ Med 2008; 12: 64. 12. The New York State Department of Health. Occupational Asthmagens. 2008. 13. Occupational Safety and Health Council. Indoor Air Quality. Sedentary Work Saf Heal Bull 2012. 14. National Health Service. Sick building syndrome. 2020. 15. Raeiszadeh et al. ACS Photonics 2020; 7: 2941–51. 16. FDA. UV Lights and Lamps: Ultraviolet-C Radiation, Disinfection, and Coronavirus. 2021.