Specialist in Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Keep the Gut Out of Mischief

The Advancement in Diagnosis for Colorectal Cancer

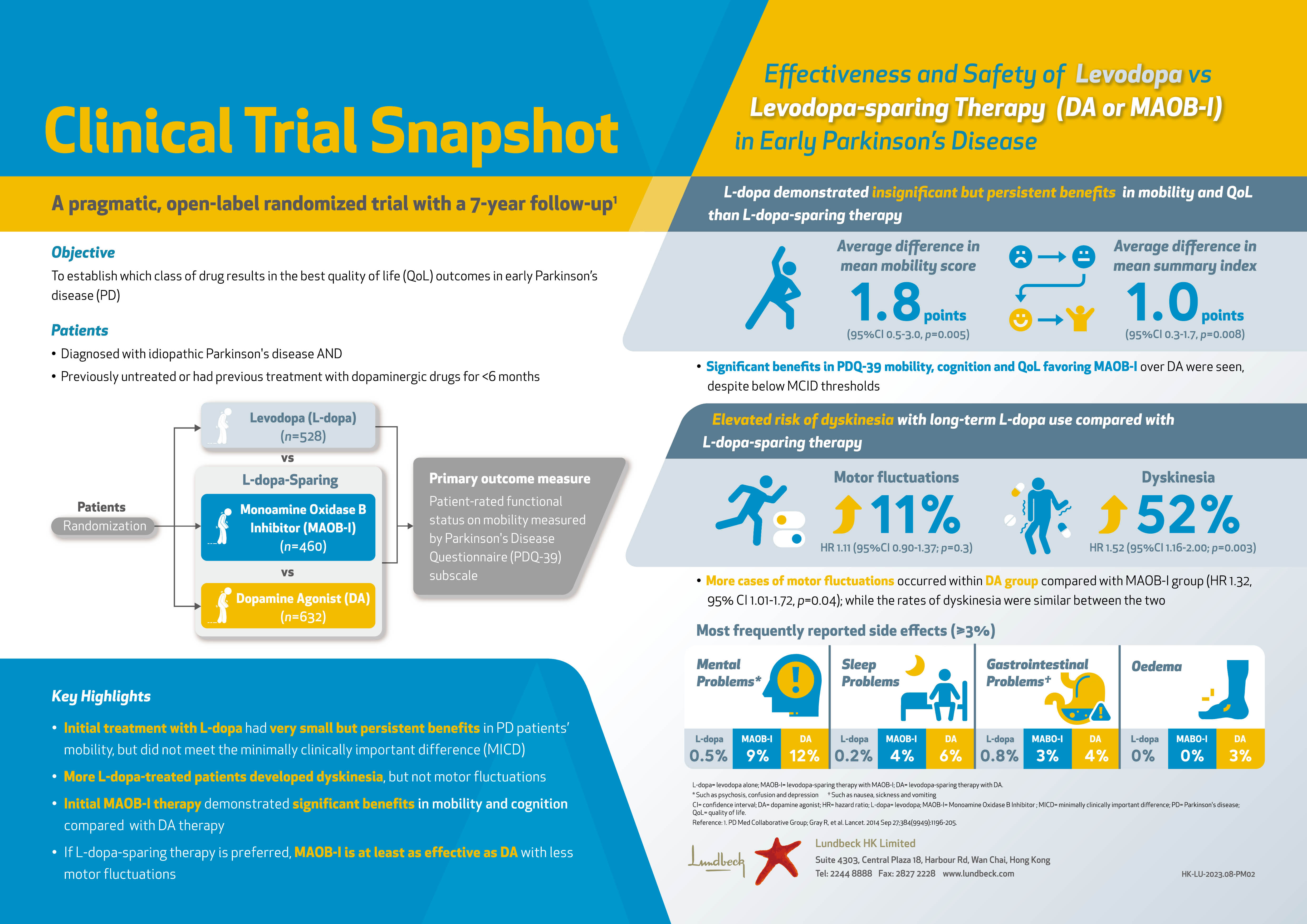

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the most common cancer, accounting for 16.6% of all new cancer cases in 2018, in Hong Kong. The disease is also the second leading cause of local cancer deaths. Essentially, an uprising trend in incidence rate of CRC has been observed since 19831. To tackle with the increasing disease burden of CRC, preventive measures such as having a healthy lifestyle and balanced diet are promoted. In line with this, regular check-up for CRC are recommended for high-risk populations. In the current interview, Dr. Fong Ka Leuk, Specialist in Gastroenterology and Hepatology, shared his expertise in diagnosing CRC and his opinions on recent advancement in diagnostic tests for the disease.

Where Are We in the Prevention of CRC?

Ageing and male gender are common risk factors for CRC. In addition, a positive family history, a history of familial adenomatous polyposis, occurrence of Lynch syndrome, development of colonic polyp, and ulcerative colitis are also well known risk factors for CRC2. Besides the non-modifiable factors, Dr. Fong outlined that modifiable factors including obesity, diabetes, physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol intake and consumption of red or processed meats would contribute to an increased risk for CRC as well.

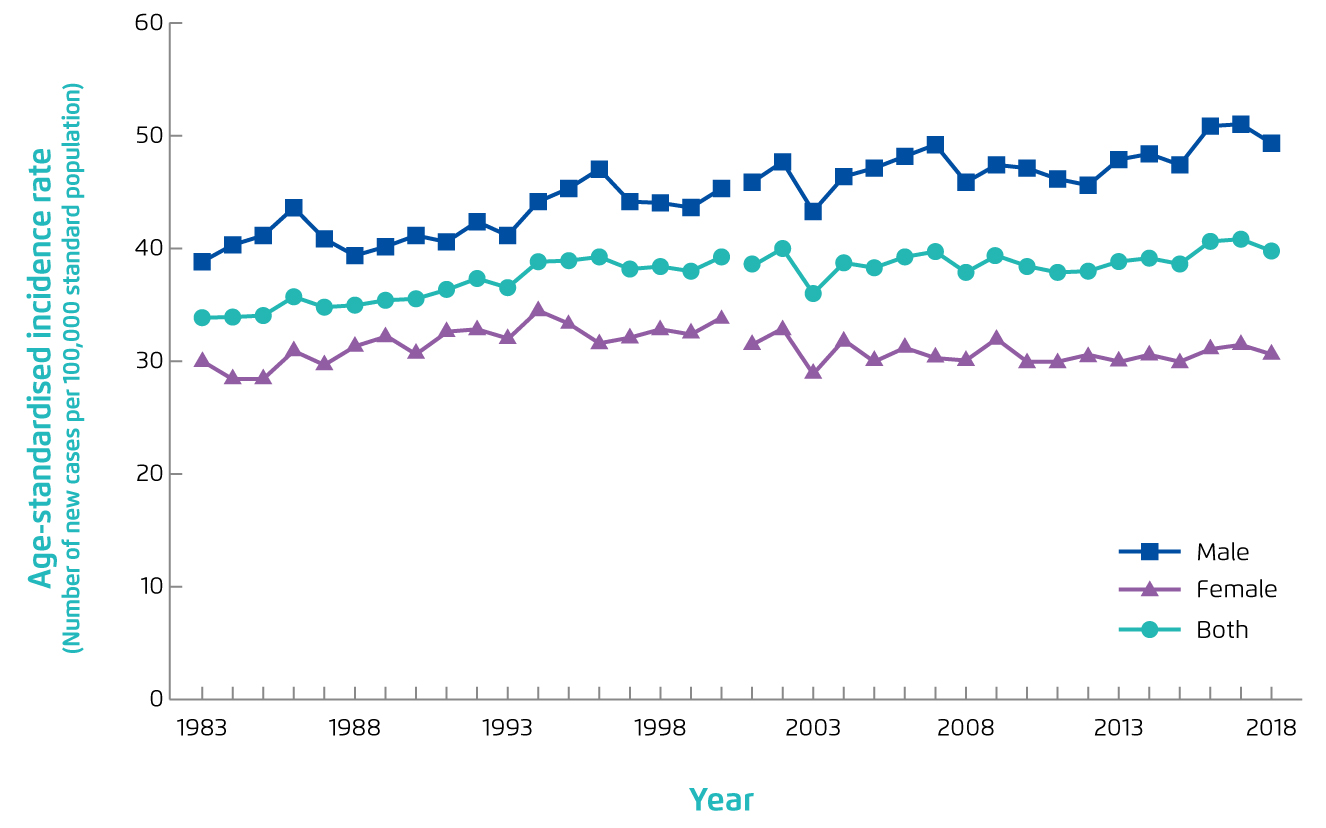

In order to prevent CRC, healthy lifestyle and balanced diet aim to control the modifiable risk factors are advocated, particularly in high-risk populations. Unfortunately, an increasing trend in local incidence of CRC has been observed since 1983 (Figure 1). Dr. Fong addressed that it would be difficult for urban people to maintain the healthy lifestyle as recommended. “We all know the benefits of physical exercises. However, it may be difficult to squeeze time for doing exercises in the tight living schedule. On the other hand, while diets with adequate dietary fibres and less red meats are beneficial, the popularity of western food limits our choice for healthy diet,” he mentioned. In addition to environment factors, Anderson et al (2015) reported that the awareness on the correlation between lifestyle factors and risk of CRC remained low, with about 60% of people in the United Kingdom did not know the links between cancer and body weight (59%) and processed meat (62%)3. Thus, further efforts on enhancing awareness on the association between healthy lifestyle and CRC are urgently needed.

To cope with this issue, Dr. Fong advised that frontline physicians to allocate more time on guidance on lifestyle modification during consultation. Notably, he suggested that the information delivered to patients has to be precise and easily understood. Also, schematic illustrations would be more effective than heavy loads of numeric medical data. In particular, Dr. Fong highlighted the use of mobile Apps. “There are many Apps equipped in mobile devices, such as smart watch, allow us to monitor the status of one’s physical activity and physiological conditions. This would help reminding people on their living habits,” he suggested.

Figure 1.

Age-standardised incidence rate of CRC in Hong Kong, 1983-2018 1

The Obstacles to CRC Screening among People at Risk

Apart from public education for enhancing awareness on CRC and promoting healthy lifestyle, early detection of CRC among high-risk populations is essential for reducing morbidity and mortality of the disease. The Colorectal Cancer Screening Programme (CRCSP) has been fully implemented in 2020 to subsidise asymptomatic Hong Kong residents aged between 50 and 75 to undergo screening tests every two years in the private sector for prevention of CRC. Under the programme, participants are subsidised to receive a Faecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) screening. If the FIT result is positive, the participant will be referred to receive a colonoscopy examination subsidised by the Government. If the FIT result is negative, the participant is advised to repeat the screening two years later4.

Meta-analyses demonstrated that FIT screening for CRC would decrease the mortality rate by 59%. Nonetheless, low participation in screening programme would limit its effectiveness. A recent report by Tsang et al (2020) addressed that the participation rate for CRC screening was only 8.3% in Hong Kong in 2017-18 for people born in 1946-19555.The report suggested that a lack of medical knowledge and awareness in general population are the major barriers to cancer screening5, whereas Dr. Fong added that psychological factors, including embarrassment and fear of potential harm, as well as time constraint would hinder participation in CRC screening.

Dr. Fong noted that it is crucial to promote the knowledge of CRC and the importance of CRC screening to the public. “Health seminars in the community and sharing sessions by peer educators who had undergone CRC screening would help alleviating the concerns towards the screening programme,” he suggested. Besides, Dr. Fong added that it is important to educate people with increased risk for CRC on the early signs and symptoms of CRC, including a persistent change in bowel habits, persistent abdominal discomfort and blood in stool, in order to facilitate early diagnosis.

CRC Diagnosis in Practice

Regarding the planning for CRC diagnostic test, Dr. Fong emphasised that it is important to know the individual’s family history on CRC or advanced polyps, especially those diagnosed in young ages, since this factor would affect the timing of the first CRC screening. For instance, if an individual has a first-degree relative suffering from CRC diagnosed at the age younger than 60, current recommendations suggest to start CRC screening by colonoscopy in the individual at the age of 40 or 10 years before the age at diagnosis of the youngest affected relative6.

In reviewing the test options for CRC screening, Dr. Fong outlined that the tests can be classified as either 1-step or 2-steps approach. “In general, all tests are classified as 2-steps approach, whereas only colonoscopy is a 1-step approach,” he described. For the 2-steps approach, a positive result in the initial part of test would indicate a subsequent colonoscopy follow-up. Faecal occult blood test (FOBT), FIT and computed tomography (CT) colonography are examples of CRC screening tests involved in 2-steps approach. Whereas, colonoscopy is a 1-step approach for detecting CRC or polyps and polypectomy can be performed if polyps are detected.

Dr. Fong commented that the sensitivity for detecting CRC of FOBT and FIT is about 75%, whereas the sensitivity for detecting polyps of the tests would be lower, at about 25-30%. The main advantages of the tests are their low costs and non-invasiveness. However, for FOBT, but not FIT, the accuracy may be influenced by certain food and medications. He further noted that the sensitivity for detecting polyps or CRC of colonoscopy is higher than 95%. However, preparation works are required by the patient and there is risk of bleeding for colonoscopy. Of note, previous review showed that screening by FOBT might reduce CRC mortality in the average risk population by 16%, whereas colonoscopy was associated with 61% reduction in CRC mortality2.

The Non-stop Evolution of CRC Diagnosis

Faecal Bacterial DNA Testing

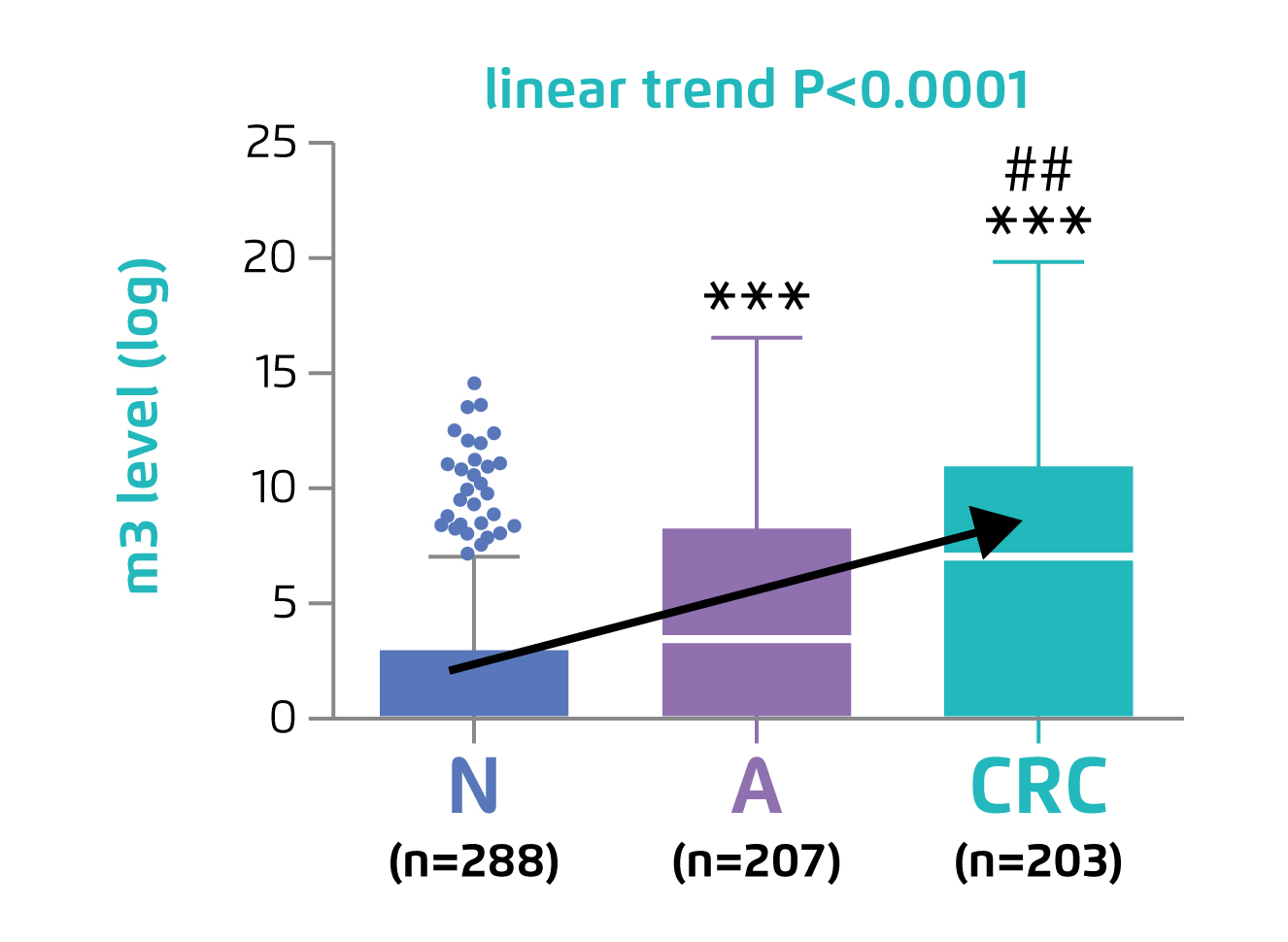

Developing diagnostic tests for CRC is a hot topic in gastroenterology and cancer research. Particularly, the application of faecal DNA testing has launched a new era in the non-invasive part of CRC screening. In particular, a research team of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) has recently identified a novel faecal Lachnoclostridium marker for the non-invasive diagnosis of colorectal adenoma and cancer. Based on metagenomic analysis of two independent Asian groups, which included 274 CRC, 353 adenoma and 385 controls, “m3” from a Lachnoclostridium sp., Fusobacterium nucleatum (Fn) and Clostridium hathewayi (Ch) were found to be significantly enriched in adenoma. Faecal m3 and Fn were significantly increased from normal to adenoma to CRC (p<0.0001, Figure 2). Essentially, the combination of m3 with Fn, Ch, Bacteroides clarus and FIT performed best for diagnosing CRC, with specificity =81.2% and sensitivity =93.8%7.

Figure 2.

Quantitative detection of faecal m37, N: healthy control, A: adenoma

Undoubtedly, the identification of the novel faecal bacterial marker m3 for the diagnosis of colorectal adenoma and CRC, with the sensitivity significantly higher than FIT and comparable to that of colonoscopy, offers an accurate non-invasive approach for early colon cancer detection. The novel test can spare patients from an unnecessary colonoscopy thus reducing the risk of invasive testing. Dr. Fong added that this test would help physicians to prioritise medical resources while the demand on colonoscopy is very high nowadays. Nonetheless, he expressed that the long-term efficacy of the diagnostic test on reducing incidence of colon cancers and associated mortality, and the optimal testing interval are still unknown. Hence, further investigations are warranted.

In response to the enquiry on the possibilities of diagnosing CRC with blood or urine instead of faecal sample, Dr. Fong commented that the sensitivity and accuracy of diagnosing colon cancers based on circulating tumour/abnormal DNA in body fluid sample are relatively low since it mainly detects more advanced CRC rather than precancerous lesions. Thus, at this moment, the body fluid samples may not be suitable for CRC screening.

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Asides the development in biomarkers, the application of computer-assisted systems in endoscopy, radiology, and pathology has improved the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of many gastrointestinal diseases. For instance, innovations in deep learning, a subfield of AI, have brought remarkable advances in image recognition, which facilitates improvement in the early detection of cancer by endoscopy, ultrasonography, and CT. In addition, AI-assisted big data analysis represents a great step forward for precision medicine.

A recent meta-analysis by Bedrikovetski et al (2021) including 17 studies on the accuracy of radiomics models and/or deep learning for the detection of lymph node metastasis in CRC by CT/MRI suggested that AI models would provide more accurate predictions on lymph node metastasis in rectal cancer and CRC as compared to radiologists8.

In addition to cancer diagnosis, Dr. Fong expected that AI would play a role in the development of personalised medicine. With the development of data-intensive biomedical assays and technologies, such as genomics, imaging protocols and wireless health monitoring devices, the demand for strategies for analyzing, integrating and interpreting the massive amounts of biomedical data has increased dramatically. Dr. Fong noted that taking the highly diversified biomedical data of an individual together, the biomedical profile generated would be personalised, whereas AI would be appropriate in accessing and integrating the data and serve as an assistant for physicians to provide personalised treatments for patients.

Trust Your Gut? Check Your Gut!

As a final remark, Dr. Fong stressed that maintaining a healthy lifestyle is crucial since many risk factors for CRC, such as obesity and smoking, can be controlled by lifestyle modification. Further, he reminded that it is important to consult a physician if abnormalities, such as a persistent change in bowel habit, have been observed so as to facilitate early diagnosis and timely treatment. “Early-stage cancers are curable,” he emphasised.

References

1. Centre for Health Protection - Colorectal Cancer. https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/healthtopics/content/25/51.html. 2. Recommendations on prevention and screening for colorectal cancer in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2018; 24: 521-6. 3. Anderson e tal. Biomed Res Int 2015; 2015. DOI:10.1155/2015/871613. 4. Eligibility of Colorectal Cancer Screening Programme updated. https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202012/30/P2020123000566.htm. 5. Tsang et al. Hong Kong Med J 2020; 26: 546-8. 6. Rex et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112: