Underutilisation of Oral Anticoagulant in the Management of Non-valvular Atrial Fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common type of arrhythmia and substantially increases the risks of stroke, systemic embolism (SE) and death. The condition affects 1-2% Caucasians and 0.7-1% of the Chinese population worldwide1. In particular, AF is common among the elderly as the prevalence tends to increase with age, from 2.6% in Chinese population aged 60-69 years increasing to 12.2% in those aged 85 or older2. Non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) is the most common form of AF which occurs in the absence of rheumatic valve disease, a mechanical or bioprosthetic valve, or mitral valve abnormalities3. Former investigations reported the incidence, mortality and cost of ischaemic stroke and major bleeding events among patients with NVAF highlighting the burden of the disease. Nonetheless, the concerns on bleeding lead to underutilisation of oral anticoagulants. Therefore, an effective strategy of anticoagulation, balancing efficacy and bleeding risk is highly desirable.

The Disease Burden of NVAF

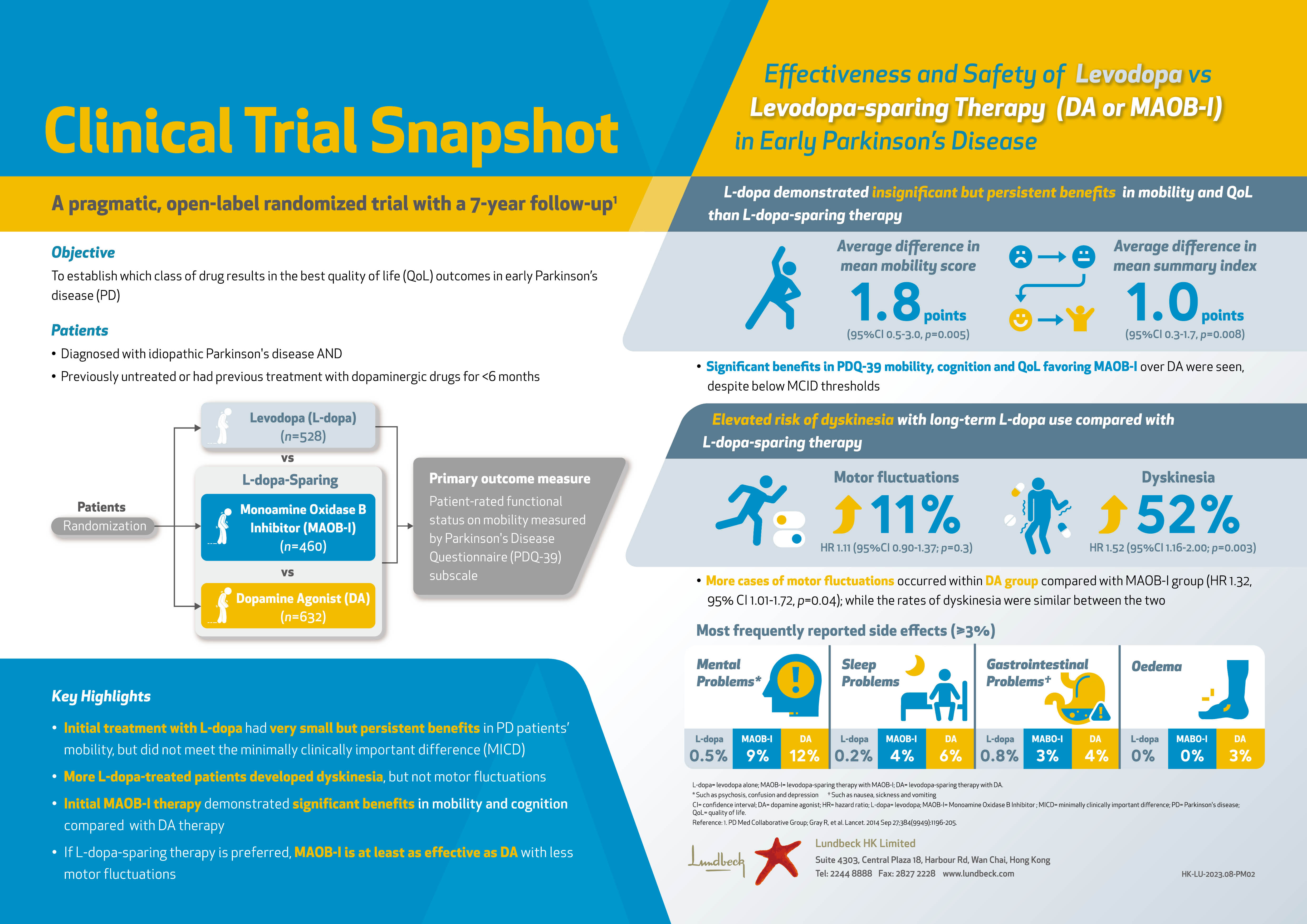

The health burden associated with NVAF has been extensively reported that it increases the risk of stroke by 3- to 5-fold, especially in elderly patients4. Elderly patients with AF often suffer from comorbidities such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as well as heart failure5. Besides, the public health and economic impact of NVAF is substantial. For instance, a recent evaluation suggested that the costs of NVAF are generated in the prevention and management of thromboembolic and haemorrhagic complications. The costs for prevention include those for examinations and medications, whereas the costs for hospitalisation are generated in uncontrolled or untreated cases (Figure 1)6. Nonetheless, it has been reported that the use of oral anticoagulants for NVAF yielded better healthcare resource utilisation (HRU) outcomes as compared to warfarin. Briefly, oral anticoagulants are associated with fewer bleeding-related hospitalisations and shorter bleeding-related lengths of stay7.

Figure 1. Total annual costs of prevention and management of thromboembolic and haemorrhagic complications6, INR: International Normalised Ratio

Underutilisation of NOACs in Patients with NVAF

In addition to improve HRU outcomes, the results of clinical trials demonstrated the improved health outcomes upon treatment with oral anticoagulants. For instance, a retrospective analysis of electronic health records and claims data involving 73,989 Japanese patients with NVAF showed that reduced-dose non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) significantly lowered the risks of stroke/SE and major bleeding versus warfarin (Figure 2A and 2B)8. Hence, international guidelines advocate NOACs as the first choice when oral anticoagulation is initiated in a patient with AF eligible for a NOAC9,10. In local clinical practice, elderly patients with NVAF are considered to have at least one major risk factor for stroke with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2, and are also recommended NOACs11.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier curves for incidence of (A) stroke/SE, and (B) major bleeding8

Despite that NOACs effectively clear clotting factors from circulation preventing blood clot formation and hence reducing the risk of stroke, they are underutilised in clinical setting, mainly due to physicians’ fear of bleeding4. In a recent real-world study, among the 6,521 patients with NVAF, 2,336 (35.8%) patients received an under-dose of NOAC. Essentially, after adjustment for patient background, under-dosing of NOAC in the patients with NVAF and creatinine clearance ≥50 mL/min was associated with a decreased incidence of bleeding, but an increased incidence of stroke/non-central nervous system SE (non-CNS SE)/myocardial infarction (MI) (Figure 3A and 3B)12. The study also revealed that high bleeding risk was the most common reason that physicians prescribed an under-dose of NOAC, followed by elderly age and renal impairment12.

Figure 3. Cumulative rates of (A) any bleeding, and (B) stroke/non-CNS SE/MI12. HR: hazard ratio

Besides, a local study revealed that the overall use of anticoagulants including both warfarin and NOACs was 66.9%, whereas the main reasons for eligible patients not receiving medication were patient refusal (20%) and physicians’ opinion (40%)13.

Besides physicians’ concerns, low compliance to medication, adverse events, and patient-physician relationship are suggested to be attributed to the underutilisation of NOACs. Moreover, for elderly patients, cognitive impairment, health literacy, involvement of caregivers, and risk of falling are major factors complicating NVAF management4. In addition, elderly patients often suffer from comorbidities which necessitate the use of multiple concomitant medications5. Thus, the increased risk of drug-drug interactions (DDIs) is also a concern in prescribing anticoagulation therapy. Of note, there are significant cultural barriers to the use of oral anticoagulation in Asian populations, hence prevalence and patients’ reliance on traditional medicines are high14.

Optimised Management for NVAF

Although NOACs can effectively reduce the risks of stroke or SE for patients with NVAF, the decision to prescribe an oral anticoagulant is complicated especially for elderly patients. In addition to balancing the stroke risk and bleeding risk associated with oral anticoagulants, factors including patients’ general health, functional and cognitive ability, caregiver availability and patient’s preference towards oral anticoagulants have to be taken into consideration as well11.

The presence of multiple comorbidities would complicate anticoagulation. For instance, patients with NVAF and renal disease have been found to be more likely to experience bleeding when treated with either warfarin or aspirin compared with NVAF only15. Thus, if medical condition changes or during acute illness, increasing frequency of anticoagulation monitoring is required for NVAF patients with comorbidities.

Besides, according to clinical opinion, involvement of a caregiver for patients with cognitive impairment is recommended to ensure compliance11. Nonetheless, proper education on patient care and medications for caregivers is essential. On the other hand, fall risk assessment followed by interventions, such as exercises for gait, education to increase safety awareness as well as prescription of appropriate walking aids, are needed for elderly patients with a risk of falling.

In prescribing medication for managing NVAF, anticoagulants with a lower risk of DDIs should be considered. In general, DDIs with NOACs are few compared to potential interactions with warfarin. Of importance, antithrombotic therapy should be individualised for patients with NVAF based on a shared decision, after discussion about the absolute risks and relative risks of stroke and bleeding as well as the patient’s values and preferences3. In summary, the optimal management for NVAF involves careful estimation of thromboembolic and bleeding risk, proper control of risk factors such as comorbidities and potential DDIs. Nonetheless, patient’s preference and their ability to deal with anticoagulation are important factors for optimising compliance.

References

1. Li et al. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40(4):222-229. 2. Zhou et al. J Epidemiol. 2008;18(5):209-216. 3. January et al. Circulation. 2014;130(23):2071-2104. 4. Benedetti et al. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2018;66(3):301-313. 5. Foody et al. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:175-187. 6. Bouame et al. J Med Econ. 2018;21(12):1213-1220. 7. Shah et al. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(1):127-139. 8. Kohsaka et al. Open Hear. 2020;7(1). 9. Kirchhof et al. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(38):2893-2962. 10. January et al. Circulation. 2019;140(2):e125-e151. 11. Wong. Hong Kong Med J. 2016;22(6):608-615. 12. Ikeda et al. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2019;48(4):653-660. 13. Lee et al. Value Heal. 2014;17(7):A483. 14. Tan et al. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;49(2):268-270. 15. Olesen et al. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(7):625-635.