Heart diseases such as acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is among the leading cause of death and affects around 3 million individuals globally1. AMI is driven by atherosclerotic plaque, and post-myocardial infarction (pMI), the risk of developing heart failure (HF) increases by 50-60%2. Notably, the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i), an antidiabetic treatment that has revolutionised the treatment for HF and chronic kidney disease (CKD), has shown a potential role in reducing the risk of hospitalisation for heart failure (HHF) in AMI patients and patients with other cardiac conditions.

Heart diseases such as AMI is among the leading cause of death in the developed world. The disease affects around 3 million individuals globally, with more than 1 million deaths recorded in the United States (US) annually1. Locally, heart disease is the third leading cause of death in Hong Kong, and according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), 80% of premature heart attacks and strokes are preventable3. Heart diseases such as AMI can be divided into non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) or, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or unstable angina, which may resemble that of an NSTEMI but with normal cardiac markers1. AMI typically occurs due to a decrease in the coronary blood flow secondary to atherosclerotic plaque rupture, leading to insufficient oxygen supply to the heart muscles. Not surprisingly, 70% of all fatal AMI cases are attributed to the occlusion caused by the atherosclerotic plaques1 and post-MI; the risk of developing HF increases by 50-60% in these patients2.

HF is a global public health concern and a significant economic burden. Despite recent treatment advances, the use and dosing of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) in patients with HF remains suboptimal4. This was highlighted in the RED-HEART study, a multicentre, cross-sectional and observational study that included HF patients in the outpatient setting from 19 cardiology centres between August 2023 and December 2023. The study demonstrated that only 48.1% of patients among the 1,923 patients with HF received the SGLT2i, a drug shown to be beneficial in patients with different spectrum of HF ejection fractions5. Considering AMI still represents the primary cause of de novo HF as it is associated with significant mortality and morbidity6, treatment and prevention remain the crucial in reducing the prevalence of HF.

"AMI is the leading cause of death, affecting around 3 million individuals globally "

Despite SGLT2i being an antidiabetic treatment, it has been shown to improve cardiovascular and renal outcomes, regardless of the diabetic status among patients7. Considering renal disease such as chronic kidney disease (CKD) is present in > 30% of patients with AMI and together, these conditions has been associated with a worse prognosis8, the use of SGLT2i may offer therapeutic benefits in patients with AMI and other cardiac pathologies. For instance, SGLT2i has also been shown to reduce the risk of atrial fibrillation (AF), according to a systematic review and meta-analysis by Zheng et al. (2022) based on 20 randomised trials involving 63,604 patients. The study reported that patients treated with was associated with a lower risk of AF, but not stroke, regardless of their diabetic status9. Nonetheless, these findings were not substantiated in other studies that showed SGLT2is exerting no beneficial effect in preventing AF, regardless of the follow-up duration, type or dose of the drug or the patient population10.

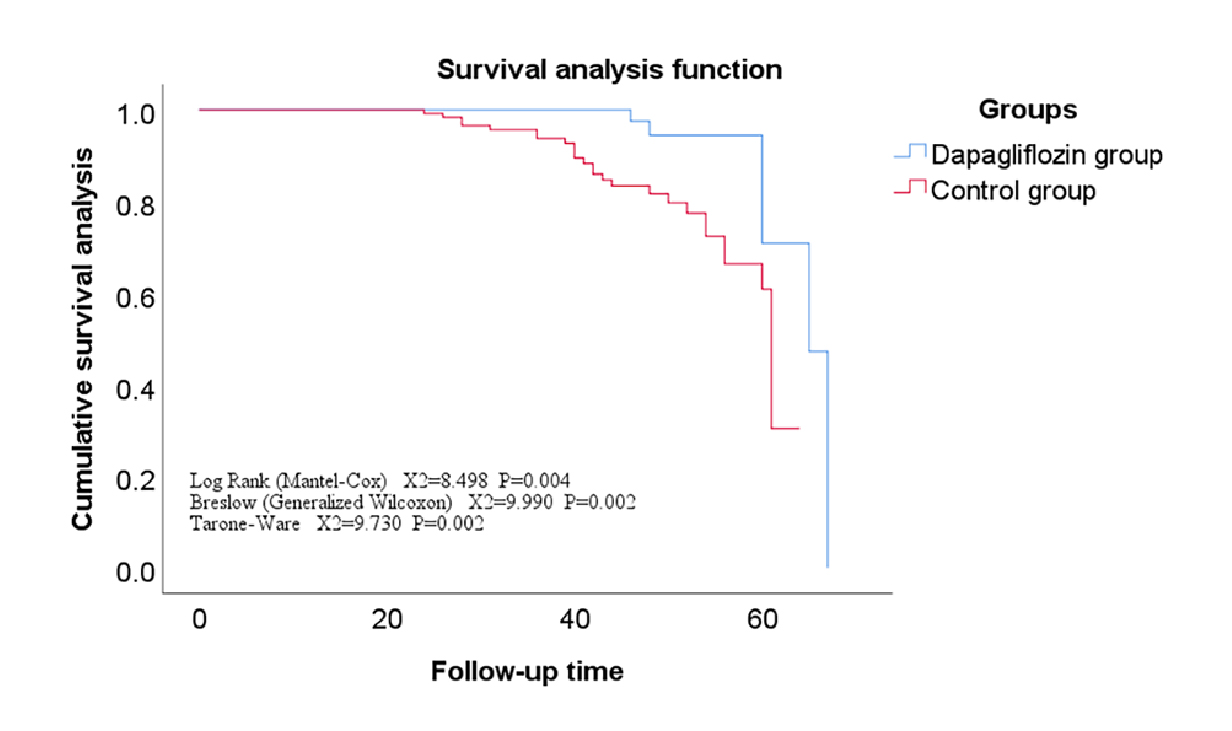

Interestingly, AF often coexists in patients with AMI and incidence of AMI has been reported in 6% to 21% of AF patients. In addition, AMI can induce AF through inflammation and atrial diastolic overload, whereas rapid heart rate of AF leads to an increase in oxygen demand and worsening of ischaemia11. The question then remains on the role of SGLT2i therapy in patients who suffered AMI. Recent studies have highlighted the potential clinical benefit of SGLT2i therapy in T2D patients with AMI and a study by Chai et al. (2025) evaluated the efficacy and prognosis of dapagliflozin (DAPA), an SGLT2i in patients with AMI complicated by T2D. During the study, 245 patients aged 34-94 were included and the primary endpoint was defined as the composite outcome of cardiac mortality, HF events, and cerebrovascular insult stroke. The secondary endpoint was defined as death resulting from cardiac and cerebrovascular causes, excluding other factors. The results showed that primary endpoint of survival was significantly higher in the DAPA group than in the control group (P<0.05) (Figure 1)13. In addition, the overall survival rate of the DAPA group was significantly higher than the control group, the difference was statistically significant (P<0.05). These findings were suggestive that combination of DAPA with conventional anti-HF drugs is not only safe, but also effective in reducing CV adverse events, and improving long-term prognosis of patients with AMI and T2D13. Similarily, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Idowu et al. (2024) reported that SGLT2i therapy after AMI is safe and is associated with a reduced risk of HHF but not the all-cause mortality12.

Figure 1: Survival curve of the main endpoint events in the dapagliflozin group versus the control13

"DAPA, an SGLT2i has shown to significantly improve the overall survival among T2D patients with AMI"

Coronary artery disease is considered the root cause of AMI and is believed to frequently coexist with aortic valve stenosis (AVS)14. Conspicuously, AVS affects around 2-5% of the adult population aged ≥75 years, and patients with cardiac ischaemic events may experience pathological remodelling of the cardiac valves. However, the evidence linking the effects of MI to AVS has previously been poorly reported in the literature until a study by Paquin et al. (2022) evaluated this relationship. The study aimed to evaluate the AVS progression in patients after AMI with or without a history of MI, followed by a pathobiological evaluation of the aortic valve leaflets in animal models with MI. 68 patients with AMI, 45 with previous MI and 101 control subjects were included in the study with all three groups having comparable baseline AVS severity. Strikingly, the study found that the AMI status was significantly associated with accelerated aortic valve area progression (p=0.008)15. Furthermore, the aortic valve in post-MI experimental animals showed a significantly increased collagen expression compared to the control. The study concluded that AVS progression is accelerated following AMI, which is caused by increased collagen production and thickening of the aortic valve after the ischaemic events. More worryingly, these findings corroborated that patients with AVS who suffered AMI may exhibit faster valvular disease progression and may require closer follow-up15.

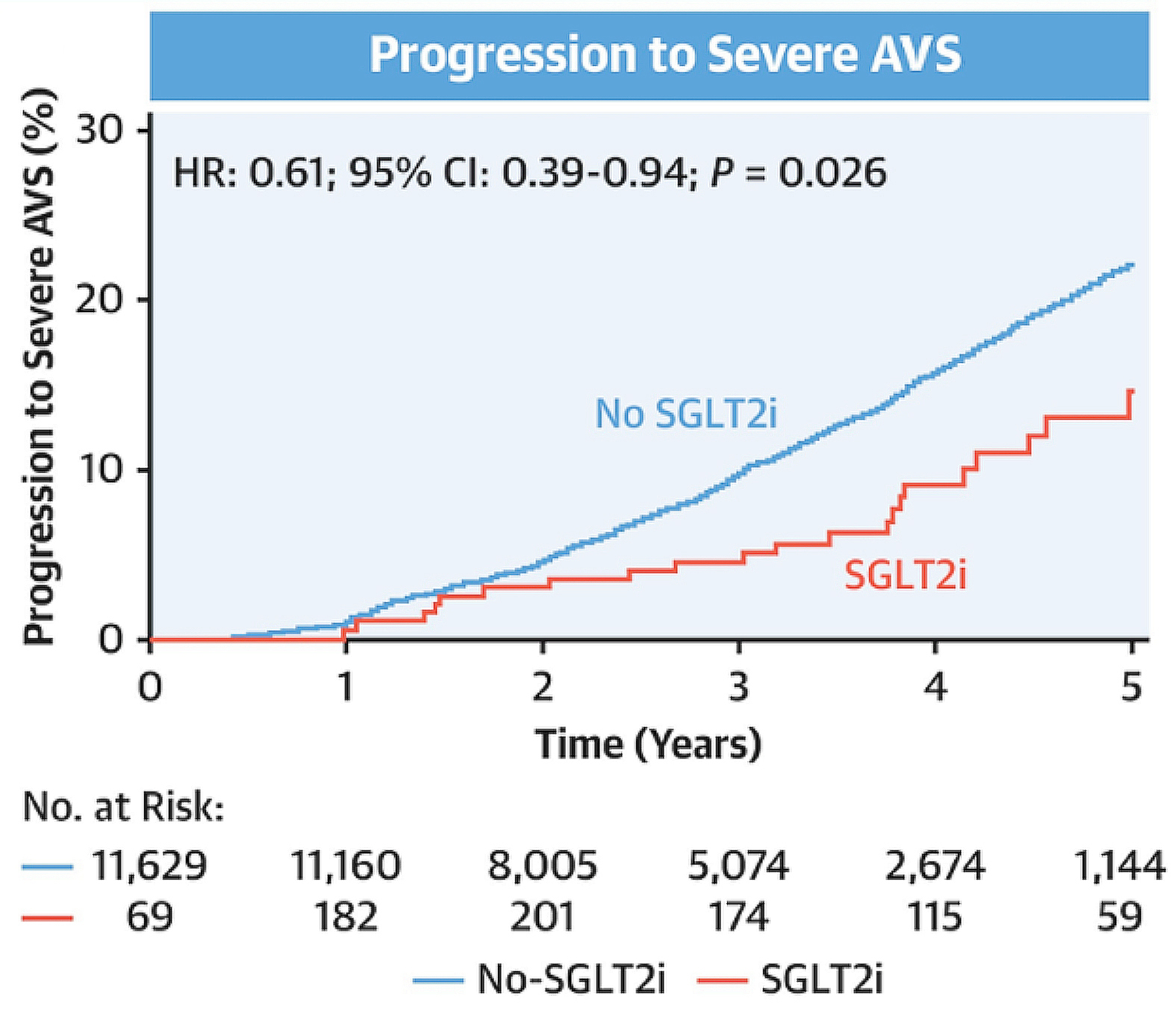

Considering the burden of AMI in patients with AVS and the lack of effective treatment, Shah et al. (2025) evaluated the role of SGTL2i in slowing the progression of AVS in view of SGLT2is having numerous pleiotropic effects on the cardiac system. Retrospective data of 458 AVS patients on SGLT2i and 11,240 AVS patients not on SGLT2i from January 2016 to September 2022 was included in the study16. Surprisingly, the study found that patients on SGLT2i were less likely to have severe AVS progression (p=0.03), and the risk was progressively lower with time (<3, 6, and 12 months, respectively), as illustrated in Figure 216. The data from the study suggested that SGTL2i may slow the progression of non-severe AVS. Arguably, patients with AMI are often understudied in SGLT2i outcome trials, and attempts should be made through large-scale randomised trials to determine efficacy and safety during early initiation, preferably within days of an AMI.

Figure 2: Progression to severe aortic stenosis with and without SGLT2 inhibitors16. AVS, aortic valve stenosis; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor.

"SGLT2i may slow the progression of non-severe aortic valve stenosis "

In summary, there is a continuing evidence gap for considering the use of SGLT2i early following AMI, and this may one day be filled and conglomerated in a holistic manner with pre-existing cardiac treatment.

References

1. Mechanic OJ, et al. StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2025. 2. Ritsinger V, et al. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020; 27(17): 1890-901. 3. Zhou Y, et al. European Heart Journal - Digital Health 2024; 5(3): 363-70. 4. Savarese G, et al. Eur J Heart Fail 2021; 23(9): 1499-511. 5. Kocabas U, et al. ESC Heart Fail 2025; 12(1): 434-46. 6. Farrero M, et al. REC: CardioClinics 2020; 55(1): 1-3. 7. Kubota Y, et al. JACC: Asia 2022; 2(3_Part_2): 287-93. 8. Freese Ballegaard EL, et al. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2024; 19(10). 9. Zheng RJ, et al. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2022; 79(2): e145-e52. 10. Zhang HD, et al. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2024; 31(7): 770-9. 11. Obayashi Y, et al. Journal of the American Heart Association 2021; 10(18): e021417. 12. Idowu A, et al. Curr Probl Cardiol 2024; 49(8): 102648. 13. Chai J, et al. Front Cardiovasc Med 2025; 12: 1500978. 14. Tomii D, et al. Circulation 2024; 150(25): 2046-69. 15. Paquin A, et al. Open Heart 2022; 9(1). 16. Shah T, et al. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 2025; 0(0).