Lupus nephritis (LN) is one of the most common organ manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), affecting more than 50% of patients1, whereas up to 20% of patients with LN eventually progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD)2. Of note, a majority of patients with LN are younger than 50 years3. This highlights the substantial disease burden and socioeconomic impact of the disease. Although several clinical guidelines for managing LN have been developed in European countries4 and the United States (U.S.)5, the differences in clinical and socioeconomic factors between Asian and non-Asian patients may influence therapeutic decisions in managing LN. To cater the specific requirements in the Asia-Pacific region, the SLE special interest group (SIG) of the Asia-Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology (APLAR) has recently published the consensus statements for managing LN specialised for the region6.

SLE is a multisystem autoimmune disease with a relapsing and remitting course, whereas kidney involvement is common and remains a major cause of mortality and morbidity. LN can be asymptomatic with urinalysis, renal function and 24 h-proteinuria within the normal range. However, the disease may also be highly symptomatic and characterised by urinary abnormalities, such as haematuria, and more overt presentations, including acute nephritic syndrome and rapidly progressive renal failure7. Moreover, other clinical features, such as elevated serum creatinine and hypertension, can be developed in some cases of LN8. The symptoms of LN often occur at the same time or shortly after lupus symptoms9.

Given the variability of clinical manifestations of LN, determination of serum creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and urinalysis for urinary albumin/creatinine ratio (uACR), urinary protein/creatinine ratio (uPCR), and/or urinary sediment, can be performed to indicate LN-related abnormalities10. Remarkably, renal biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosing LN when proteinuria is identified. Renal biopsy provides information on the degree of inflammation and the extent of damage and helps rule out other causes of proteinuria or renal dysfunction in SLE patients1.

The burden of LN shows race and ethnicity-related disparities. According to a retrospective analysis of the California Lupus Surveillance Project (CLSP) by Maningding et al. (2020), Black (prevalence ratios [PR]: 1.74), Asians/Pacific Islanders (API, PR: 1.68), and Hispanic (PR: 1.35) SLE patients demonstrated significantly increased prevalence of renal manifestations versus Whites (p<0.001 for all). Furthermore, both Blacks (PR: 1.09, p<0.001) and APIs (PR: 1.07, p<0.05) had increased prevalence of hematologic manifestations. The results also indicated higher risks of developing antiphospholipid syndrome among APIs (hazard ratio [HR]: 2.5) and Hispanics (HR: 2.6) than Whites. Essentially, APIs were reported to have the highest risk of developing LN (HR: 4.3), followed by Blacks (HR: 2.4) and Hispanics (HR: 2.3), as compared to Whites11.

Apart from disease burden, the randomised controlled trial (RCT) by Appel et al. (2009) reported that serious infections and deaths developed in a substantial proportion of Asian patients with LN treated with higher doses of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF)12. This highlights the potential risk of adverse responses to immunosuppressive therapies among Asian patients.

On the other hand, it is crucial to realise the impact of socioeconomic factors on the management of LN in the Asia-Pacific region. Accordingly, the organisation of healthcare structure and delivery, financial limitations, education level and compliance of patients, as well as environmental and climate factors differ significantly among Asian regions. These factors would alter patients' access to standard-of-care and clinicians' treatment decisions13.

Interestingly, the belief about medicines among Asian SLE patients has been reported to be different from the British/Irish Whites in that the former were more concerned about the toxicities of drug therapies, particularly immunosuppressive medications14. Hence, patients of South Asian origin tend to terminate immunosuppressive therapy sooner than those in Northern Europe15.

By virtue of the specific epidemiology, socioeconomic and cultural background, patient adherence, and the pattern of treatment response regarding LN in Asia-Pacific region, a set of consensus statements specialised for managing LN in this region is highly desirable.

The consensus statements on the management of LN for the Asia-Pacific region were formulated by the SLE SIG established under the Scientific Committee of the APLAR. The core group reviewed the literature by means of a PubMed search using keywords derived from a set of Population Intervention Comparison Outcome (PICO) questions. An initial list of 56 statements was drafted and selected by the core group members based on the search results and clinical practice6.

The level of evidence and strength of recommendation of the proposed statements were evaluated in 3 rounds of Delphi exercise, which involved anonymous voting and feedback done via an online platform by 46 medical practitioners, including 31 rheumatologists, 13 nephrologists, 2 renal histopathologists, from 21 Asia-Pacific regions, and 2 LN patients. The agreement score was derived from a Likert scale in which participants were required to vote for the level of agreement with the statements. Statements with agreement by at least 80% of the voting members reached consensus6.

After the Delphi exercise, 48 consensus recommendations were finalised, which were categorised into overarching principles, diagnosis and monitoring, initial and subsequent therapies, pure membranous LN, patients at risk of renal progression, adjunctive therapies and management of comorbidities, and renal replacement therapy6.

Regarding the overarching principles in LN management, the consensus advocated that a shared decision between patients and physicians is required, whereas the goals of treatment and patient adherence are underscored. Besides, the consensus recommended monitoring LN using clinical and laboratory parameters. Additional tests are recommended if a flare-up is suspected. In particularly, kidney biopsy is suggested to characterise the disease’s conditions16.

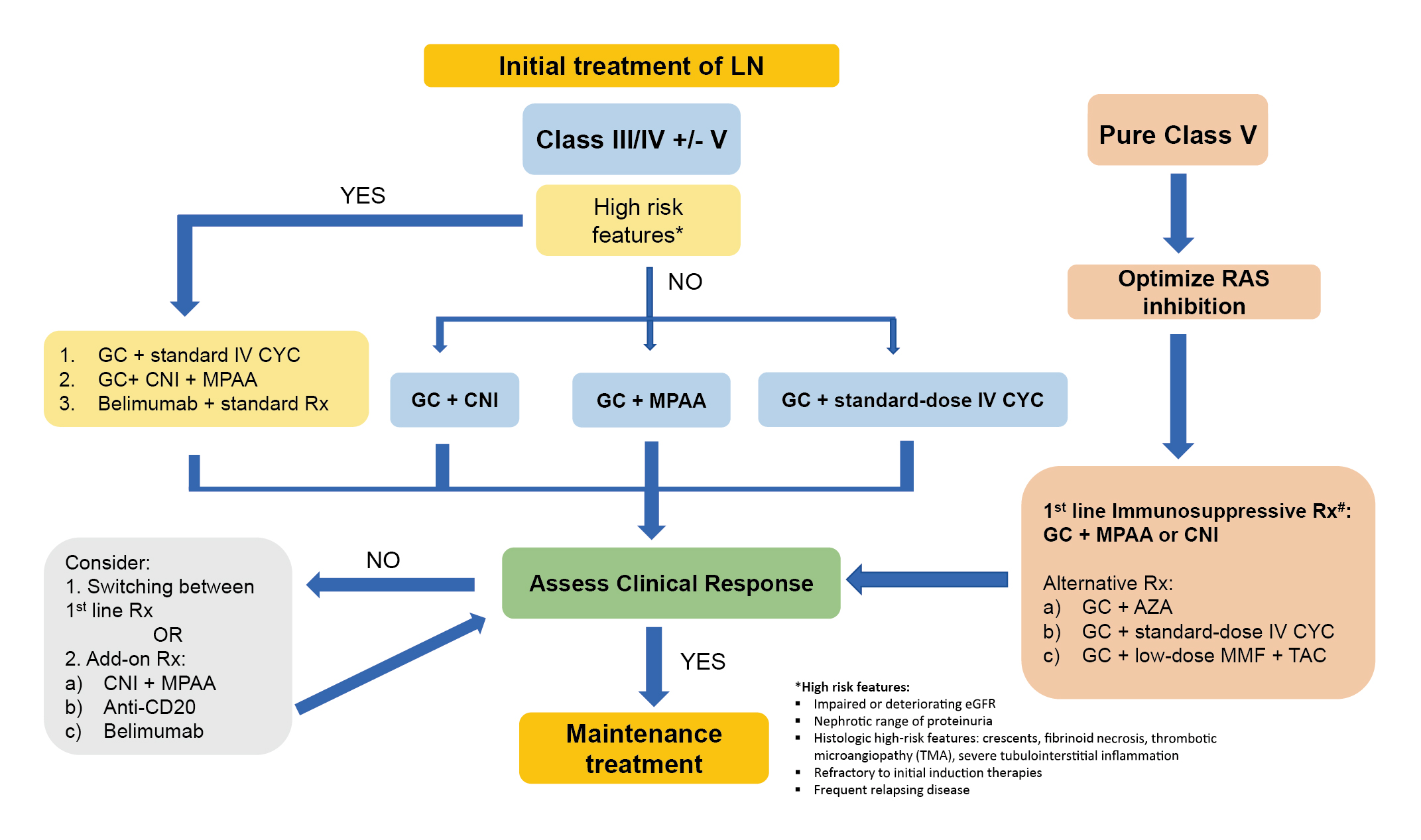

A major focus of the consensus is on the initial and subsequent therapies of LN. For initial treatment of LN, a combination of glucocorticoids (GCs) with cyclophosphamide (CYC), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), or calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) is recommended as the first-line options. Additionally, an upfront combination of immunosuppressive drugs and biological agents may be considered in patients at significant risk of disease progression and renal function deterioration. For refractory diseases, switching or add-on among different immunosuppressive agents, including biological agents, may be considered (Figure 1)6.

Figure 1: Initial treatment of LN recommended in APLAR Consensus6, IV: intravenous; MPAA: mycophenolic acid analogue; Rx: treatment; TAC: tacrolimus

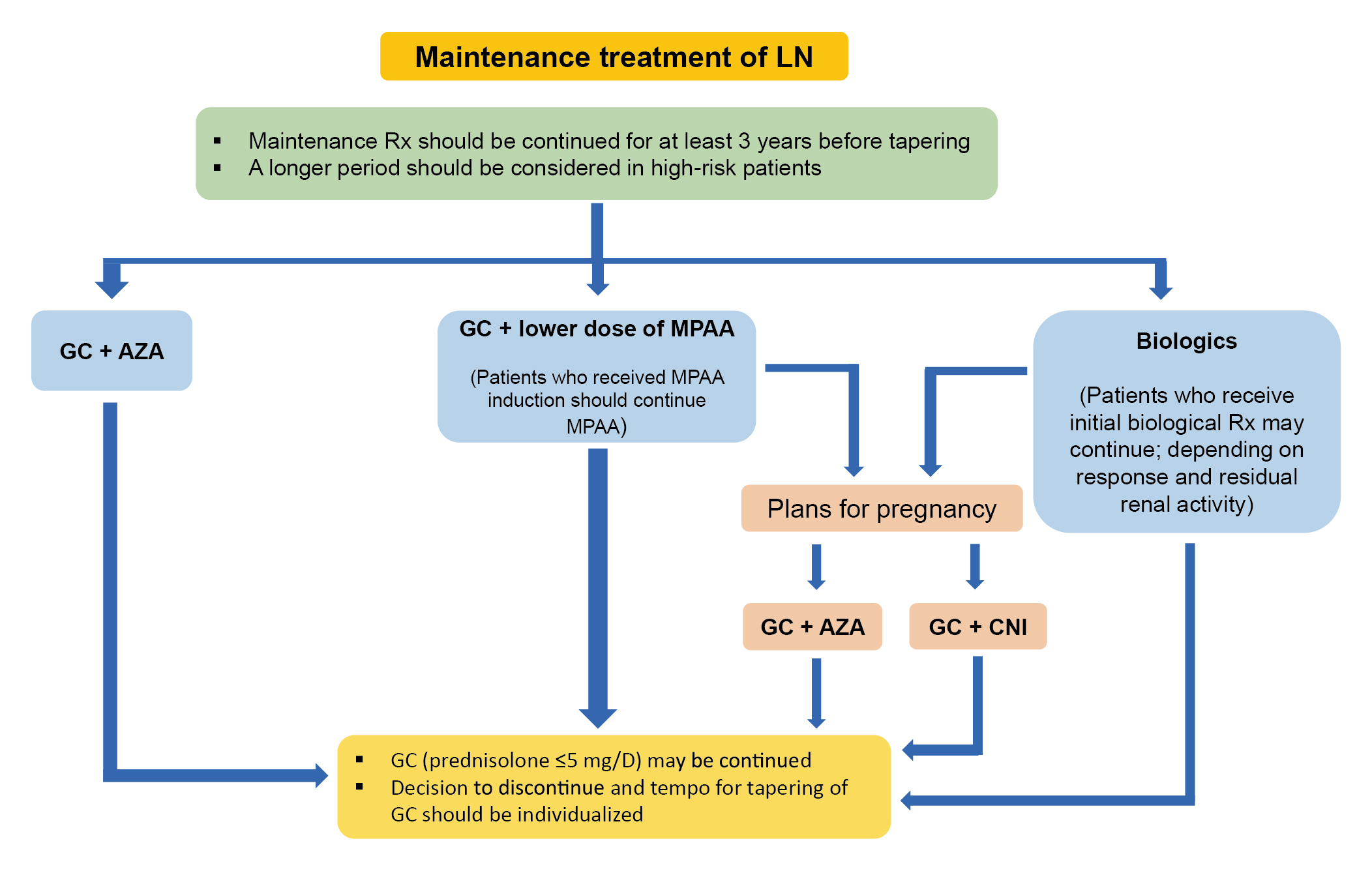

The consensus recommended that maintenance therapy of LN should follow induction regimens when the target response is achieved and continue for at least 3 years to reduce the risk of renal flares. Remarkably, lower-dose MMF and azathioprine (AZA) can be considered, whereas MMF maintenance should follow induction by the same drug. On the other hand, low-dose prednisolone may be continued at a dose of 5 mg/day or less, and the decision to discontinue GCs and the tempo for tapering should be individualised (Figure 2)6.

Figure 2: Algorithm for maintenance treatment of LN6

The use of adjunctive therapies and the management of LN-related comorbidities are also covered in the consensus. For instance, the universal use of hydroxychloroquine in all SLE patients is recommended. Moreover, regardless of hypertension status, the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockade is recommended for all LN patients. Essentially, lifestyle modification, anticoagulation, control of cardiovascular risk factors, prevention of osteoporosis, drug-related toxicities, as well as infective complications are advocated in the consensus statements. Last but not least, the consensus addresses recommendations on renal replacement therapies, the use of immunosuppressive agents during dialysis, and the optimal timing for kidney transplantation6.

Given the comprehensive coverage of opinions on managing LN by clinical experts and patients from various Asia-Pacific regions, the 2024 APLAR consensus on the management of LN is expected to provide holistic guidance tailored for physicians managing LN patients in the region.

References

1. A1. Alforaih et al. J Appl Lab Med 2022; 7: 1450–67. 2. Mahajan et al. Lupus 2020; 29: 1011. 3. Tektonidou et al. Arthritis and Rheumatology 2016; 68: 1432–41. 4. Fanouriakis et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2020; 79: S713–23. 5. Hahn et al. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012; 64: 797. 6. Mok et al. Int J Rheum Dis 2025; 28. DOI:10.1111/1756-185X.70021. 7. Gasparotto et al. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020; 59: v39. 8. Wang et al. Arch Rheumatol 2017; 33: 17. 9. Lupus & Kidney Disease (Lupus Nephritis) - NIDDK. 10. Rojas-Rivera et al. Clin Kidney J 2023; 16: 1384. 11. Maningding et al. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2020; 72: 622–9. 12. Appel et al. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 20: 1103. 13. Mok et al. Nephrology 2014; 19: 11–20. 14. Kumar et al. Rheumatology 2008; 47: 690–7. 15. Helliwell et al. Rheumatology 2003; 42: 1197–201. 16. Yap et al. Int J Rheum Dis 2025; 28. DOI:10.1111/1756-185X.70022.