Editor-in-Chief, V·Pulse

Watching movies is one of the most popular leisure activities globally, and many people spend a substantial amount of time and money on it. In particular, the popularity of the horror genre is constantly increasing, contributing to a huge commercial success. Yet, the primary aim of horror movies is to frighten, shock, horrify, and disgust the audience. Given that movies can subtly influence people’s perception of reality1, the psychosocial impacts of horror movies are worth considering. The objectives of this article are to discuss people’s preference towards horror movies, to review the physiological responses when watching horror movies, and to evaluate the potential psychosocial impact associated with this movie genre.

While fear is distressful and unpleasant by nature, it is worth considering how and why people find pleasure in this emotion. In the existing literature, fear has been defined as the conscious unpleasant feeling that one has when in the presence of a threat to well-being, which is often but not always accompanied by behavioural and physiological defensive reactions2. Of note, Andersen et al. (2020) recently coined the mixed emotional experience of fear and enjoyment as "recreational fear"3.

There have been various explanations for the phenomenon of recreational fear. Remarkably, curiosity helps explain horror consumption behaviours. Jirout and Klahr (2012) defined curiosity as the threshold of desired uncertainty in the environment that leads to exploratory behaviour4. It has been argued that curiosity is aroused when individuals have their expectations violated. While phenomena with too much uncertainty and surprise would render it chaotic, unmasterable, and displeasurable, those with little to no uncertainty or surprise would render an experience boring and unmotivating5.

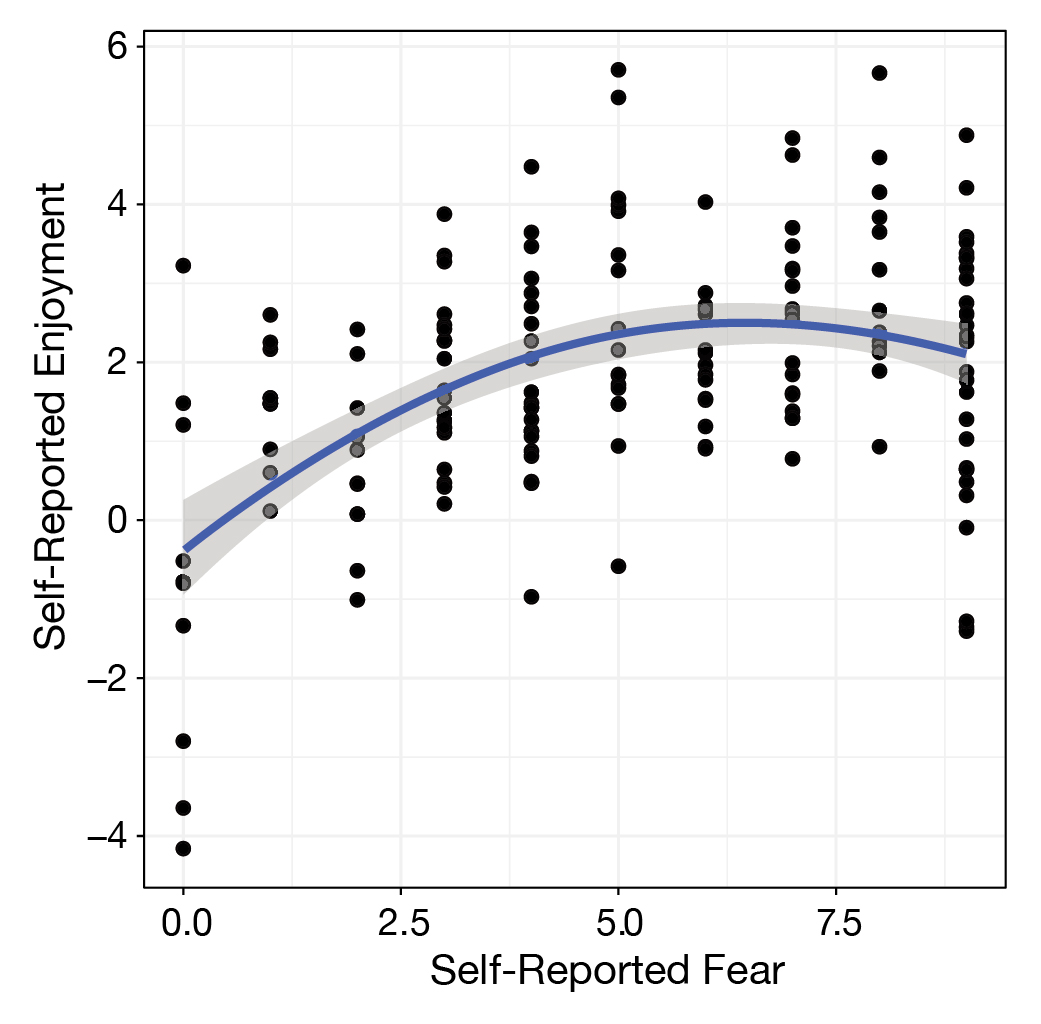

Andersen et al. (2020) conducted a field study involving 110 individuals aged 12-57 at a haunted house attraction to evaluate the association between fear and enjoyment of recreational fear. The results indicated that self-reported enjoyment has an inverted-U-shaped relationship with self-reported fear measures (Figure 1)3. The essential idea is that recreational fear provides a context in which individuals can have risk-free experiences with fear and related emotions without being in actual danger.

Figure 1. The relation between self-reported enjoyment and self-reported fear3

Some people enjoy the intense sensations when watching horror movies, while others do not. Accordingly, investigations have attempted to visualise the brain mechanisms underlying such inter-individual differences. In the study by Straube et al. (2009), 40 healthy subjects were recruited to watch threatening and neutral scenes from horror movies during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The patterns of increased activation in the anterior cingulate cortex, insula, thalamus, and visual areas by threatening and neutral scenes were compared6.

The results illustrated that movie-induced anxiety correlated positively with activation in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (Figure 2A), suggesting a role for this area in the subjective experience of being scared. While the thalamus and anterior insula, as well as visual areas, are involved in the induction and representation of arousal states, brain activation to threat versus neutral scenes in these regions was positively correlated with sensation-seeking scores. In contrast, significantly negative correlations between sensation-seeking scores and brain activation were found in the insula and thalamus during neutral movie clips6. Essentially, this cerebral hypoactivation seems to be compensated by intense sensations as provided by threat scenes in horror movies, partly explaining people’s enjoyment of watching horror movies.

Figure 2. fMRI showing an increased brain activation to threatening against neutral movie scenes in A) anterior cingulate cortex, B) the insula, C) the thalamus, and (D) the visual areas6

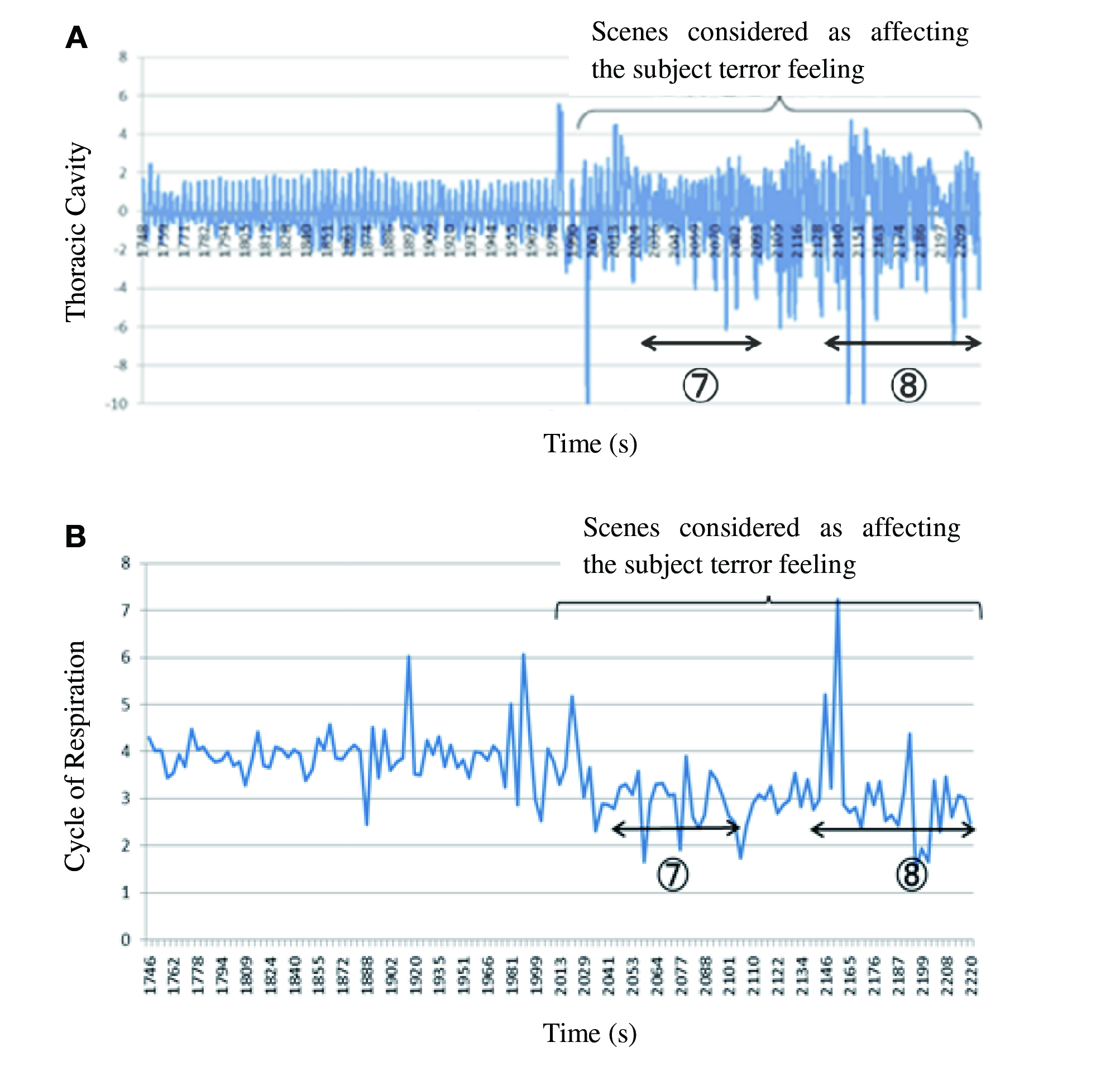

Apart from the increased activation in brain regions, various organ systems also respond to the excitement when watching horror movies. In an investigation by Fukumoto and Tsukino (2015), 10 male students were recruited to watch a horror movie. The subjects’ physiological data, such as respiration patterns and skin conductance, were measured. Additionally, subjective ratings on terror feelings induced by the movie were conducted immediately after watching the movie7.

The results demonstrated that the intensity of respiration increased significantly, and the cycles of respiration were shortened during the scenes, which was considered to affect the feeling of terror for the subject (Figures 3A and 3B). Besides, skin conductance, reflected by Galvanic Skin Response (GSR), increased upon the terror stimuli during the movie7. The findings revealed some of the physiological responses that occurred while watching horror movies. Of course, further investigations on other physiological data, such as electrocardiogram (ECG), will provide a more comprehensive description of the physiological impacts of horror movies.

Figure 3. Change in respiration pattern of a subject who felt terrified during threatening scenes (labeled as 7 and 8)7

While the nature of fear is unpleasant, there are opinions claiming that terror scenes in horror movies might be felt as distressingly real and could presumably induce psychological harm to the viewers. Araújo et al. (2019) reported the case of a 10-year-old girl who developed a posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)-like syndrome after watching the horror movie “Scary Movie 3” with a friend, but not a real-world traumatic event. The patient claimed she could not sleep due to the fear caused by the scary movie scenes repeatedly playing in her mind. She could not sleep alone for several years after the exposure, and any attempt to sleep alone would cause her intense hypervigilance and anxiety. The patient has still fulfilled the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD after 6 years8. In fact, there are other case reports suggesting that horror movies can constitute a traumatic stressor under specific circumstances, which would be a concern in particular for individuals in the developmental stage.

In contrast to the risk of adverse outcomes, there is literature advocating the positive consequences of watching horror movies. For instance, Miller et al. (2023) opined that horror movies can provide a valuable source of information for learning about potentially volatile and highly newsworthy scenarios, and fictional horror content provides a relatively low-stakes arena for learning about high-stakes scenarios9.

Interestingly, Scrivner et al. (2021) found that people who had seen more horror movies reported increased psychological resilience during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. The report also found that the trait of morbid curiosity was associated with positive resilience and interest in pandemic movies during the pandemic. Hence, these results suggested that horror movies might serve adaptive purposes, allowing audiences to practice effective coping strategies that can be beneficial in real-world situations10.

Undoubtedly, horror movies provide both fear and enjoyment for people and are one of the most popular genres worldwide. According to existing literature, people watch horror movies for sensation seeking. Essentially, there is a “just right” level between fear and enjoyment in recreational fear. Despite the reports on its benefits, the findings on the physiological and psychological consequences of horror movies are inconsistent. Nonetheless, it would be more realistic to watch movies based on one’s personal interest rather than the potential benefits. Thus, let’s enjoy the movies regardless of genre!

References

1. Till et al. PLoS One 2014; 9. DOI:10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0102293. 2. LeDoux. Trends Cogn Sci 2013; 17: 155–6. 3. Andersen et al. Psychol Sci 2020; 31: 1497–510. 4. Jirout and Klahr. Developmental Review 2012; 32: 125–60. 5. Clark. Phenomenol Cogn Sci 2018; 17: 521–34. 6. Straube et al. Hum Brain Mapp 2010; 31: 36–47. 7. Fukumoto and Tsukino. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 2015; 9339: 500–7. 8. de Araújo et al. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicopatologia Fundamental 2019; 22: 360–75. 9. Miller et al. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2024; 379. DOI:10.1098/RSTB.2022.0425. 10. Scrivner et al. Pers Individ Dif 2021; 168: 110397.