Doctor at the National Health Services (NHS), United Kingdom (UK)

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is an enveloped retrovirus (HIV-1 and HIV-2) that contains 2 copies of a single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) genome1. It causes the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) which is the last stage of HIV infection1. HIV is thought to have originated from non-human primates sporadically throughout the 1900s. However, it was not until the 1980s when the virus came to the world¡¦s attention as homosexual males in urban areas began presenting with advanced and unexplained immunodeficiencies2. Individuals infected by the virus often complain of symptoms related to the primary infection, after which a long chronic phase of HIV infection begins and last for decades1. Notably, HIV continues to pose a serious health threat globally with 37.7 million individuals affected by the disease since the year 2020 with further 1.5 million new cases reported in the same year, globally3. HIV infection is one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality, globally but is highly concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa due to the prevalence of promiscuous practice with poor education of sexually transmitted infections (STIs)4.

Locally, the prevalence of HIV remains relatively low, with only 10,280 cases of HIV infection reported since the 1984 to the December 2019. However, within these cases, those above the age of 20 infected and the virus has dramatically increased over the last few years and 78% of these infections are acquired through unprotected sexual intercourse4. Traditionally, antiretroviral therapy (ART) is used to treat HIV infection, in addition to prevent uninfected individuals of acquiring the disease (pre-exposure prophylaxis [PrEP])5. However, recent studies have highlighted the unmet needs in current HIV treatment, particularly among drug users, who are often considered as a high-risk group for HIV infections. These individuals often have a poor clinical outcome due to poor social support and limited access to the healthcare system6. In addition, the poor clinical outcome reported in individual with HIV infection is also related to the poor adherence to ART, since ART treatment often require close to 100% compliance and anything below that increases the risk of multidrug resistance7. Therefore, to understand this enigma, we will first need to understand the unmet needs of ART treatment and how the emerging treatment may change the landscape of the ART treatment in future8.

As we know ART is not a curative treatment for HIV infections since it does not eradicate the virus, instead it can block the new onset of HIV infections. However, if the treatment is interrupted at any stages, the viral replication resumes, and the viral load can rise exponentially within days to weeks. Therefore, it is paramount that the ART is continued indefinitely in patients with HIV infections5. Recent epidemiologic studies have highlighted that there are approximately 38% of patients with HIV who are non-adherent to their ART, and this remains one of the unmet treatment needs of ART considering treatment adherence close to 100% is require for ART to be effective against the viral replication9. So, what are the reasons behind the poor patient compliance to ART? Well, non-adherence is partly related to personal factors such as mental health issues, substance abuse or other social stigma. Furthermore, some patients with HIV infection may find the once-daily dose regimen difficult to adhere5. Therefore, emphasis has recently been placed on the disease prevention10 and the use of PrEP has gained more popularity over the last few years, particularly in men who have sex with men (MSM)11.

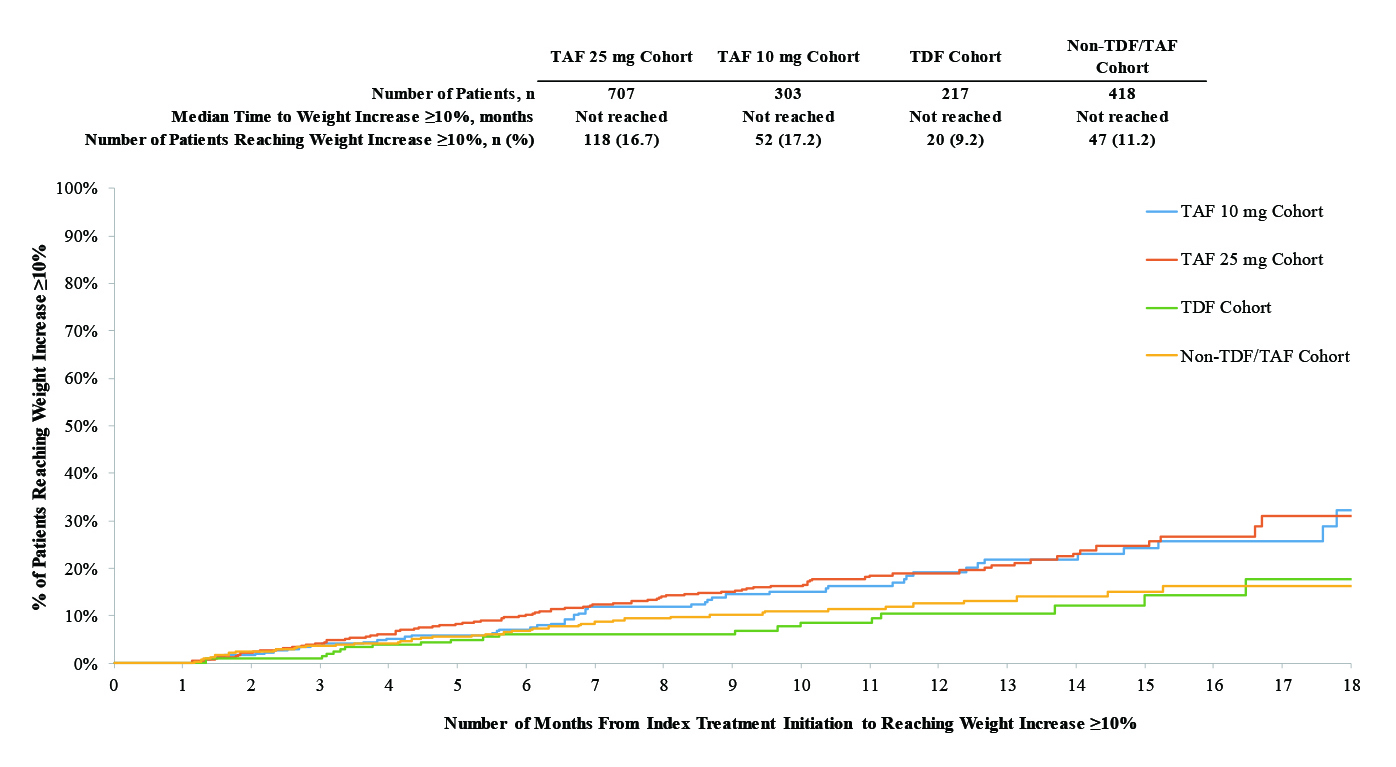

Currently, there are two PrEP treatment options, the tenofovir disproxil fumarate (TDF) and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)12. Both TDF and TAF are oral based treatments taken once daily and offers close to 99% protection against HIV transmission through rectal and vaginal exposure. However, due to the potential serious side-effects related to TDF13, TAF is a preferred choice with a better safety profile14. Nevertheless, the therapeutic benefit of TAF is not as prevalent in individuals who are exposed to HIV virus through receptive vaginal intercourse12. Furthermore, the therapeutic benefit of TAF used in combination with emtricitabine (FTC), a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) in African females exposed to HIV virus does not seem to confer as much benefit as in other ethnic groups15. Moreover, very recent studies on TAF use in pregnant females with HIV showed TAF use was associated with more weight gain compared to TDF even though the regimen appeared to be safe and effective during pregnancy (Figure 1)16,17. As a result, these may form the basis of non-adherence which is further exacerbated by the fact that the discontinuation rate of multi-tablet regimens (MTR) is much higher than that of once-daily, single-tablet regimen (STR)18.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Curves of Time to Weight Gain or BMI Increase ≥5% or ≥10%16.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Curves of Time to Weight Gain or BMI Increase ≥5% or ≥10%16.

Currently, there are two approved treatments for HIV-1 infection, and these include bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (B/F/TAF) and cabotegravir plus rilpivirine (CAB+RPV). So, what are the differences between these treatments? B/F/TAF is a once daily tablet that is shown to be effective against HIV-1 infection in patients with no treatment-emergent resistance19. The efficacy of B/F/TAF has been substantiated in BASE trial, which is a phase 4, single-arm study that evaluated the effectiveness and safety profile of B/F/TAF in patients with HIV, and substance use disorder (SUD). The study included 43 participants with a median age of 38 and the primary endpoint was the proportion of participants with HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL at week 24. The secondary endpoints were the proportion of participants with HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL at week 48, safety, and B/F/TAF adherence, substance use and quality of life (SF-12). The conclusion drawn from the study suggested B/F/TAF use among high-risk population resulted in an initial 72% viral suppression rate at week 24; however, this rate dropped to only 49% at week 48. The reported rate in this study was much lower than those published in other clinical trial (89-96%)20. In addition, the risk of drug resistance may increases with B/F/TAF in the setting of suboptimal adherence21.

On the other hand, CAB+RPV is a combined injectable, long-acting treatment for HIV-1 with similar efficacy and safety to B/F/TAF. This was demonstrated in the ATLAS-2M trial which was an open-labelled, phase 3 randomised study involving 1,045 participants with HIV-1 infection recruited from 13 different countries. They were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive CAB+RPV long-acting every 8 weeks or every 4 weeks22. The study found that the CAB+RPV combination every 8 weeks was non-inferior to dosing every 4 weeks (HIV-1 RNA ≥50 copies per mL; 2% vs 1%) with an adjusted treatment difference of 0.8 (95% confidence interval [CI]: -0.6 to -2.2)22. The conclusion drawn from the study was that the efficacy, and safety profiles of dosing every 8 and 4 weeks were similar. Furthermore, the results supported the use of CAB+RPV long-acting administration every 2 months as a therapeutic option for patients living with HIV-1 infection22. Not surprisingly, patients preferred every 8 weeks regimen over the 4-week regimen and daily dosing22.

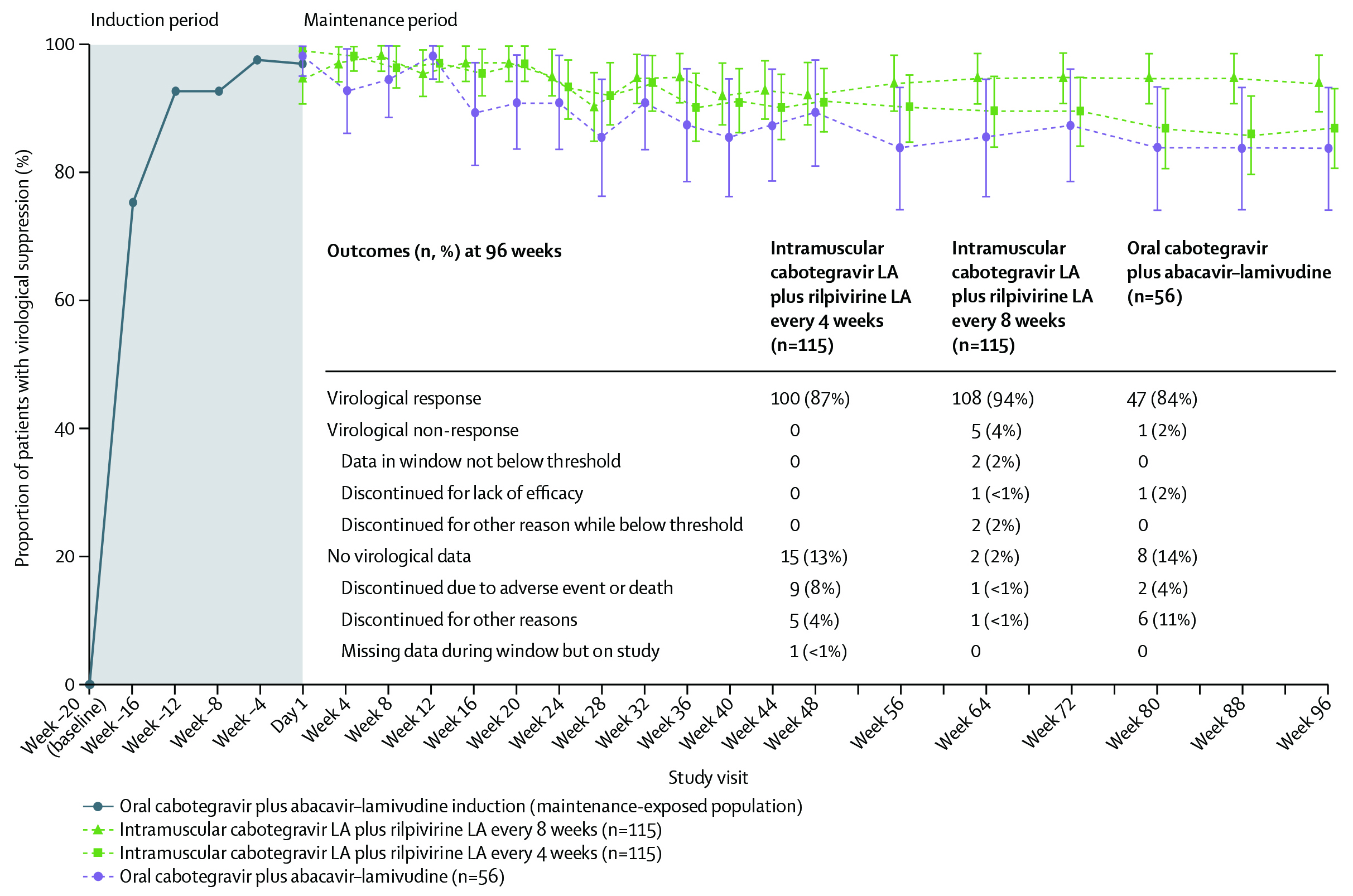

The therapeutic effects of CAB+RPV was evaluated further in LATTE-2 trial, which was a phase 2b trial with 309 patients with HIV-1 randomised to receive oral cabotegravir 30 mg plus abacavir-lamivudine 600-300 mg once daily and after 20-week induction period, patients were randomly assigned 2:2:1 to intramuscular long-acting CAB+RPV at 4-week interval or 8-week intervals or continued oral cabotegravir plus abacavir-lamivudine23. Astonishingly, the viral suppression was maintained at week 96 to around 84% in oral treatment group, 87% among 4-week group and 94% in 8-week group (Figure 2)23 . The conclusion drawn here was that the long-acting combination of CAB+RPV either every 4 or 8 weeks was as effective as daily three-drug oral therapy at maintaining HIV-1 viral suppression throughout the 96 weeks with well accepted tolerance level23.

Figure 2. Proportion of patients with HIV-1 RNA concentration less than 50 copies per mL (FDA snapshot algorithm) by visit in the maintenance-exposed population and snapshot outcomes at week 9623. Error bars shows 95% Cis, derived using the normal approximation. CI= confidence interval; FDA= US Food and Drug Administration; LA= long-acting.

Figure 2. Proportion of patients with HIV-1 RNA concentration less than 50 copies per mL (FDA snapshot algorithm) by visit in the maintenance-exposed population and snapshot outcomes at week 9623. Error bars shows 95% Cis, derived using the normal approximation. CI= confidence interval; FDA= US Food and Drug Administration; LA= long-acting.

In December 2014, the Jointed United Nation Programme on HIV/AIDS released the 90-90-90 initiative with the goals of 90% of all individuals with HIV knowing their diagnosis, 90% of those diagnosed are on treatment and 90% of those on treatment achieving viral suppression24. As a mean of reducing the pill burden, the standard of care of ART regimen includes once-daily, fixed dose regimens with two or three drugs in combination such as B/F/TAF and is recommended by HIV-1 treatment guidelines as an initial therapy for individuals with HIV-1 infections. Even though these drug combinations are effective and well tolerated among HIV-1 infected patients, the daily oral ART regiment may pose inherent challenges among these individuals due to the stigma and fear of disclosure of their condition. This may inadvertently lead to a poor overall health, quality of life, treatment adherence, and satisfaction25.

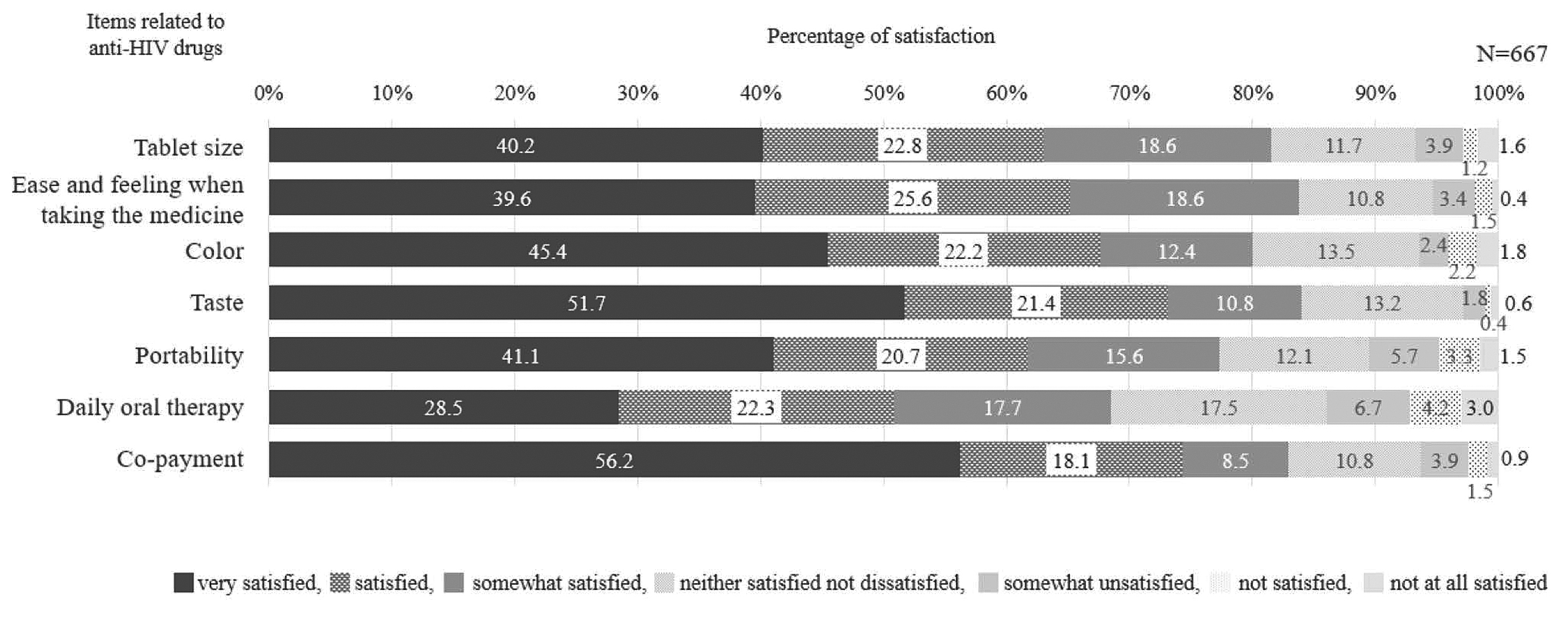

To further understand this phenomenon, Ishihara et al., (2023) performed a prospective multicentered cross-sectional observational study which recruited 667 patients with HIV who had received ART for at least one month. The study found patient satisfaction was the lowest with daily oral dosing

(p= 0.044), and tablet size (p=0.042); hence, preferred long-acting injectable (Figure 3)26.

Figure 3. Satisfaction with individual items among anti-HIV drugs. The questionnaire included seven items related to anti-HIV drug taking (tablet size, ease and feeling when taking the medicine, colour, taste, probability, daily oral therapy, and co-payment). Participants ranked their answer on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 6 (very satisfied) to 0 (very dissatisfied)26.

Figure 3. Satisfaction with individual items among anti-HIV drugs. The questionnaire included seven items related to anti-HIV drug taking (tablet size, ease and feeling when taking the medicine, colour, taste, probability, daily oral therapy, and co-payment). Participants ranked their answer on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 6 (very satisfied) to 0 (very dissatisfied)26.

Long-acting therapies may address some of the challenges associated with daily oral ART, particularly the reported risk of pill fatigue, treatment adherence, and the social stigma faced by individuals with HIV. In SOLAR trial, among 687 participants randomly assigned to switch to either long-acting intramuscular cabotegravir (600 mg) plus rilpivirine (900 mg) dosed every 2 months or to continue daily oral B/F/TAF25. The primary efficacy endpoint was proportion of participants with virological non-response (HIV-1 RNA ≥50 copies per mL; the US FDA snapshot algorithm, 4% non-inferiority margin; modified intention-to-treat exposed population) at month 11 (long-acting start with injection group) and month 12 (long-acting with oral lead-in group and B/F/TAF group)25. The study found that at months 11-12, long-acting CAB+RPV showed non-inferior efficacy versus B/F/TAF with an adjusted treatment difference of 0.7 (95% CI -0.7 to 2.0). The study concluded that the long-acting CAB+RPV combination dosed at every 2 months had similar efficacy as B/F/TAF but may help address the unmet psychosocial needs associated with daily oral treatment25. Moreover, the long-term efficacy of CAB+RPV was substantiated in ATLAS-2M trial that evaluated the long-acting suppression of CAB+RPV for up to week 152. The study demonstrated the virologic suppressive ability of CAB+ RPV dosed at either 4 or 8 weeks lasted for approximately 3 years and confirmed long-term efficacy, safety, and tolerability of CAB+RPV as a complete regimen to maintain HIV-1 virologic suppression27. In conclusion, there is no doubt that the long-acting ARTs would help improve the treatment adherence, but the challenge remains since implementation of such therapy is difficult as not every individual with HIV-1 infection may have access to this type of treatment. Therefore, the year long HIV injections are currently being explored and may address unmet needs and challenges faced by both patients and clinicians.

References

1. Justiz Vaillant AA, et al. StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2023. 2. Deeks SG, et al. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2015; 1(1): 15035. 3. Cervantes CE, et al. Current HIV/AIDS Reports 2023; 20(2): 100-10. 4. Zhang F, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18(14). 5. Landovitz RJ, et al. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2023; 21(10): 657-70. 6. Dasgupta S, et al. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv 2021; 20(4): 1-14. 7. Schaecher KL. Am J Manag Care 2013; 19(12 Suppl): s231-7. 8. Brizzi M, et al. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2023; 10: 20499361221149773. 9. Buh A, et al. PLOS ONE 2023; 18(4): e0283991. 10. Straubinger T, et al. Front Pharmacol 2019; 10: 1514. 11. Nozza S, et al. BMJ Open 2022; 12(12): e067261. 12. Krakower DS, et al. Ann Intern Med 2020; 172(4): 281-2. 13. Fioroti CEA, et al. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2022; 64: e10. 14. Fong TL, et al. J Viral Hepat 2019; 26(5): 561-7. 15. Celum C, et al. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2012; 25(1): 51-7. 16. Emond B, et al. J Health Econ Outcomes Res 2022; 9(1): 39-49. 17. Thimm MA, et al. J AIDS HIV Treat 2022; 4(1): 6-13. 18. Cohen J, et al. AIDS Research and Therapy 2020; 17(1): 12. 19. Sax PE, et al. eClinicalMedicine