Consensus Recommendations on COVID-19 Vaccination in Adult Patients with Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases by the HKSR

Clinical opinions generally advocate that COVID-19 vaccination is a critical measure to contain the current pandemic. Notably, patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases (ARDs) are particularly at increased risk of severe COVID-19 infection because of disease-related medical comorbidities1. Nonetheless, vaccine hesitancy associated with the uncertainty on safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines has hindered public participation in the current vaccination program. Thus, the Hong Kong Society of Rheumatology (HKSR) has recently published consensus recommendations in order to address the opinions of local rheumatologists and to guide frontline clinicians as well as public on COVID-19 vaccination in patients with ARDs.

Risk of Severe COVID-19 Infection in Patients with ARDs

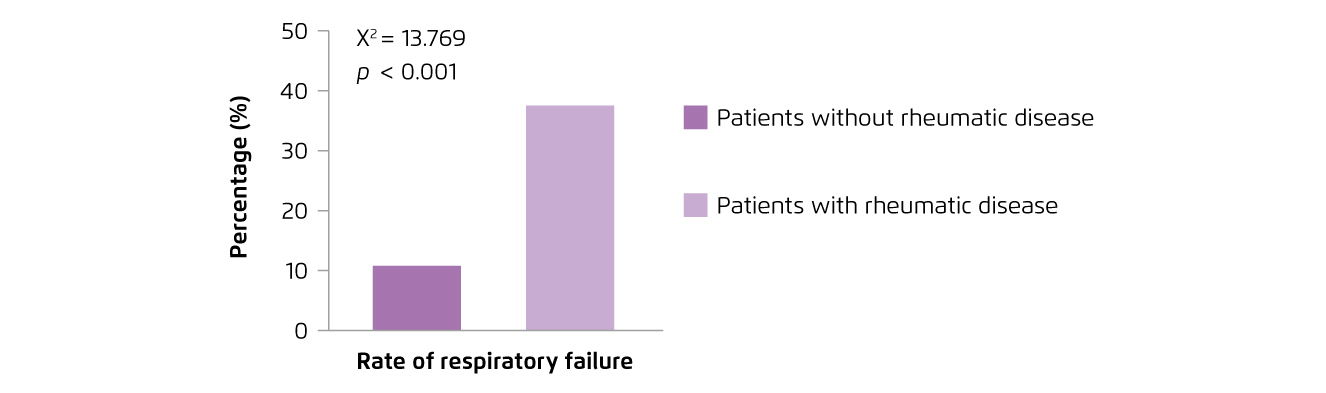

Patients with ARDs are expected to be at increased risk of suffering from severe outcomes upon COVID-19 infection because of immunosuppressive therapies and/or immunodeficiency. A retrospective case series study conducted in early 2020 involving 2,326 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China indicated that the odds of respiratory failure was significantly higher among rheumatic patients as compared with non-rheumatic comparator (38% versus 10%, p < 0.001, Figure 1)2. Besides, a recent comparator cohort study in the United States, involving 2,379 COVID-19 patients with systemic ARDs and 2,379 matched non-rheumatic comparators, demonstrated that patients with systemic ARDs had a significantly higher risk of hospitalisation (relative risk [RR]: 1.14, 95% confident interval [CI]: 1.03-1.26), intensive care unit (ICU) admission (RR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.03-1.68), acute renal failure (RR: 1.81, 95% CI: 1.07-3.07) and venous thromboembolism (RR: 1.74, 95% CI: 1.23-2.45) when compared to COVID-19 patients without systemic ARDs1. Previous clinical findings thus highlighted the increased risk of severe outcomes in patients with ARDs and COVID-19 infection.

Figure 1.

Rates of COVID-19-associated respiratory failure in rheumatic patients2

Vaccine Hesitancy

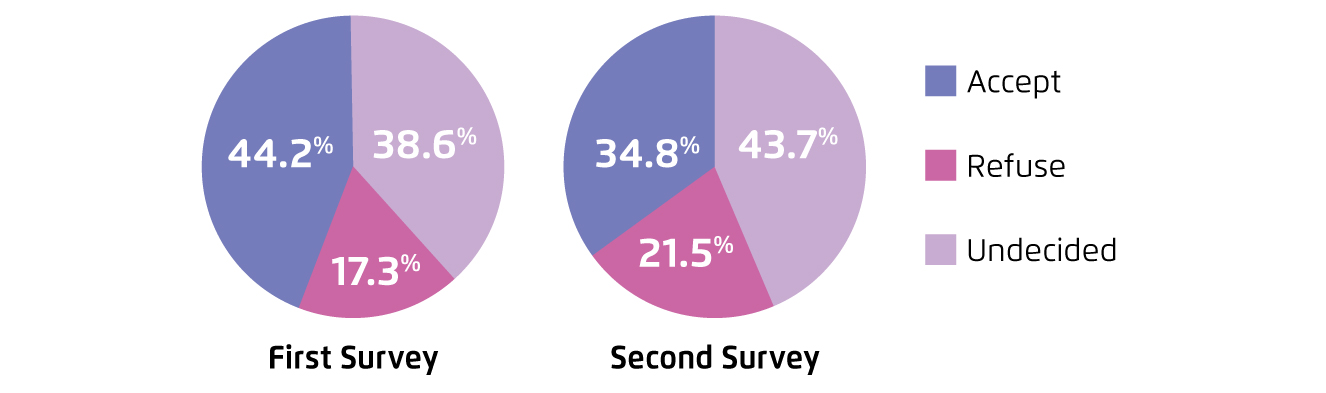

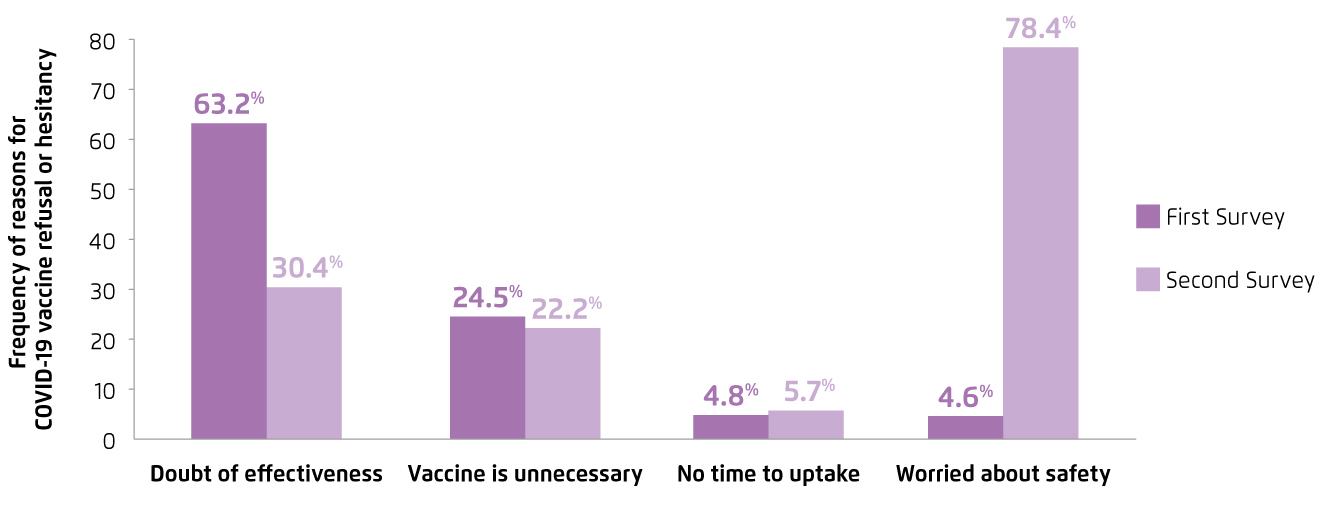

Although the local health and economic burden associated with COVID-19 is substantial, the acceptance for COVID-19 vaccines has be reported low. Former repeated cross-sectional studies on local working population reflected that the acceptance for COVID-19 vaccines was 44.2% during the first wave of epidemic, and had declined to 34.8% during the third wave (Figure 2). The results further revealed that the concerns over effectiveness and safety of COVID-19 vaccines were the major reasons for vaccine refusal or hesitancy (Figure 3)3. Essentially, the infodemic of false information about COVID-19 and vaccination plays a crucial role in the development and spreading of vaccine hesitancy. For instance, an analysis on the global flow of information on anti-vaccination views among Facebook users illustrated that anti-vaccination clusters managed to become highly entangled with undecided clusters in the main online network, whereas pro-vaccination clusters were more peripheral4. On the other hand, a survey on 1,663 British people by the Centre for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) reported that one in six people were unlikely to agree being vaccinated against COVID-19. The results highlighted that individuals who relied on social media for information on the current pandemic were more hesitate about vaccination5. Hence, while false information about COVID-19 and vaccination are widely shared on the internet, health education by the primary care sector and expert advices are important for increasing vaccination coverage.

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Standardised rate of willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccines between surveys3, first survey: first wave of epidemic, second survey: third wave of epidemic

Figure 3.

Reasons for COVID-19 vaccine refusal or hesitancy3

Development of Consensus Statements

While the recommendations by frontline clinicians, especially specialists, would help resolving the concern on appropriateness for COVID-19 vaccination from patients with ARDs and hence improving willingness to receive vaccination, the HKSR took the lead to develop a set of consensus recommendations for the use of COVID-19 vaccines in adult patients with ARDs. The statements would serve as a guideline for rheumatologists and frontline clinicians as well as general public on COVID-19 vaccination in patients with ARDs.

A committee consisted of 27 core members of the HKSR, including council members and rheumatologist-in-charge of public hospitals, was formed and a teleconference among committee members was conducted to discuss clinical questions related to COVID-19 vaccination in adult patients with ARDs. A list of 8 statements was finalised by 3 core members of the HKSR6.

A modified Delphi exercise involving 55 full members of the HKSR was performed. Delphi members were provided with the results of systematic literature research, explanatory notes, evidence grading (QOE) and strength of recommendation (SOR) of the statements. Anonymous online voting by the Delphi members was conducted to indicate the level of agreement for each statement. Feedback on statements and reasons for decision were also collected during voting. A level of agreement of 80% was regarded as representing consensus, whereas statements failed to reach consensus were revised according to the comments received and were subjected to subsequent round of voting until consensus was reached6.

Highlights of Recommendations

The consensus statements cover 3 major clinical areas including the incidence and impact of COVID-19 infection in patients with ARDs, the efficacy and adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccination in patients with ARDs, and the effect of concomitant medications on the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines and the need to adjust the dosage schedules6.

The consensus agreed that there was limited evidence suggesting an increased risk of COVID-19 infection for patients with ARDs, whereas the patients may develop more severe COVID-19 infection as compared with general population6. Although clinical data on risk-to-benefit ratio of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with ARDs are yet to be available, the consensus recommended vaccination against COVID-19 for patients with ARDs according to local guidelines and precautions of the respective vaccines since the benefit of vaccination probably out-weights its risk6.

In evaluating the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccination in patients with ARDs, members generally agreed that the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines might be compromised in view of the concomitant immunomodulating/immunosuppressive medications6. However, there is no evidence suggesting that adjusting the dosage of immunosuppressive therapy would enhance the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccination. Nonetheless, there is no evidence of increased risk of disease flares or adverse events in ARDs, in the absence of other comorbidities, after COVID-19 vaccination6.

Practically, in patients receiving heavy immunosuppressive or multiple treatment modalities, discussion with rheumatologists is recommended when planning for COVID-19 vaccination6. In particular, the consensus recommended that in patients receiving rituximab, COVID-19 vaccine is best administered shortly before the next due dose. When the underlying ARDs are stable, postponement of rituximab infusion for 4 weeks might be considered6.

The consensus statements serve as guidelines for clinicians in advising patients with ARDs on COVID-19 vaccination. Hopefully, the evidence-based recommendations would resolve patients’ concern on efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccination and the associated vaccine hesitancy.

Of note, the committee advocated that the benefits of both CoronaVac® and Comirnaty® would outweigh the risks is the current situation. Nonetheless, further evidence on outcomes of other upcoming vaccines in patients with ARDs is needed.

References

1. D’Silva et al. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021; 73: 914-20. 2. Ye et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2020; 79: 1007-13. 3. Wang et al. Vaccines 2021; 9: 1-15. 4. Johnson et al. Nature 2020; 582: 230-3. 5. Burki. Lancet Digit Heal 2020; 2: e504-5. 6. So et al. J Clin Rheumatol Immunol 2021; 21: 7-14.