The Establishment of Consensus Statements on Management of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus for Asia-Pacific Region

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multi-systemic autoimmune disease characterised by periods of exacerbation and remission, with organ damage accrued as a result of disease activity and complications of treatment, which ultimately leads to significant impairment in health-related quality of life (HRQOL), both physically and mentally1. Despite the establishment of several guidelines for the management of SLE from European countries and the United States2-5, the variations in disease severity and associated comorbidities, response and tolerability to medications as well as cultural factors may influence the therapeutic decision between Asians and non-Asians. To fulfil the unmet need, the SLE special interest group of the Asia-Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology (APLAR) has formulated the consensus statements on the management of SLE specialised for the Asia-Pacific region6.

The Rationale of Consensus Recommendations for SLE Management in Asia-Pacific Region

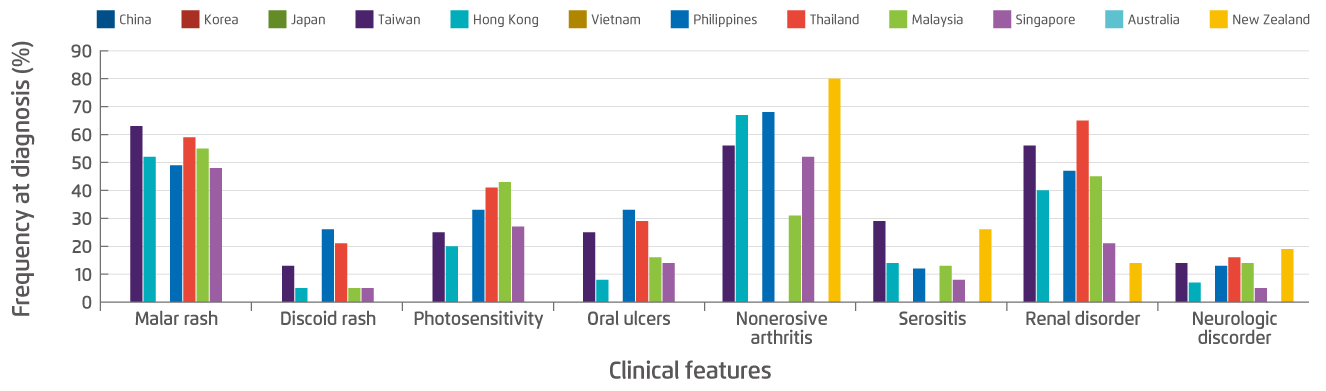

The disease burden of SLE is substantial globally. However, the epidemiology, pathophysiology as well as health outcomes of SLE vary considerably across countries. For instance, Lewis and Jawad (2017) reported ethnic disparity in the burden of SLE that SLE occurs more frequently in African people, followed by Hispanic, Asian and Caucasian individuals. Essentially, black, East Asian, South Asian and Hispanic individuals with SLE tend to develop more severe disease with a greater number of manifestations and accumulate damage from lupus more rapidly7. In particular, higher rates of renal involvement were observed among Asians as compared with Caucasians (Figure 1), making it one of the main organs involved at death. Besides, the most common neuropsychiatric manifestations attributed to SLE were seizure disorders, cerebrovascular diseases and acute confusional state8, whereas those reported in Asian SLE patients were psychosis, headache and cognitive dysfunction9-13.

Figure 1. Frequency of key clinical features at diagnosis of SLE in the Asia-Pacific region14

Variations in prognosis of SLE among ethnic groups have been reported as well. Hiraki et al (2011) demonstrated that, among patients with new onset lupus nephritis-associated end-stage renal disease (ESRD), 51% were African and 24% were Hispanic, whereas mortality was almost double among African versus white people (odds ratio [OR]: 1.83, p<0.001)15. Moreover, variations in response and tolerability to medications among SLE patients of different ethnic groups were observed. For instance, a recent meta-analysis involving 56 studies on lupus nephritis (LN) treatment reported a higher rates of serious infections in Asian than non-Asian patients (4.1-25% in Asian vs. 4.4-8.5% in non-Asian), and so were the infection-related mortality rates (0-6.7% in Asian vs. 0-2.1% in non-Asian)16.

The differences in culture and clinical settings further highlight the need of recommendations on SLE management specialised for the Asia-Pacific region. The belief about medicines, particularly immunosuppressive drugs, in Asian SLE patients have been reported to be different from the British/Irish whites in that the former were more concerned with the toxicities of drug therapies17. Moreover, patients of South Asian origin were shown to terminate immunosuppressive therapy sooner than the North Europeans18. Poorer tolerance to drugs such as higher rate of dermatological reactions and cultural belief were attributed to the lower adherence rate among Asian patients. Practically, the accessibility to healthcare facilities and the availability of medications for SLE may be lower in certain Asian countries limiting the choice of therapies in SLE management19. In view of the differences in clinical manifestations, responses to treatment and clinical settings, consensus recommendations on SLE management specialised for Asia-Pacific region are warranted.

Consensus Formation

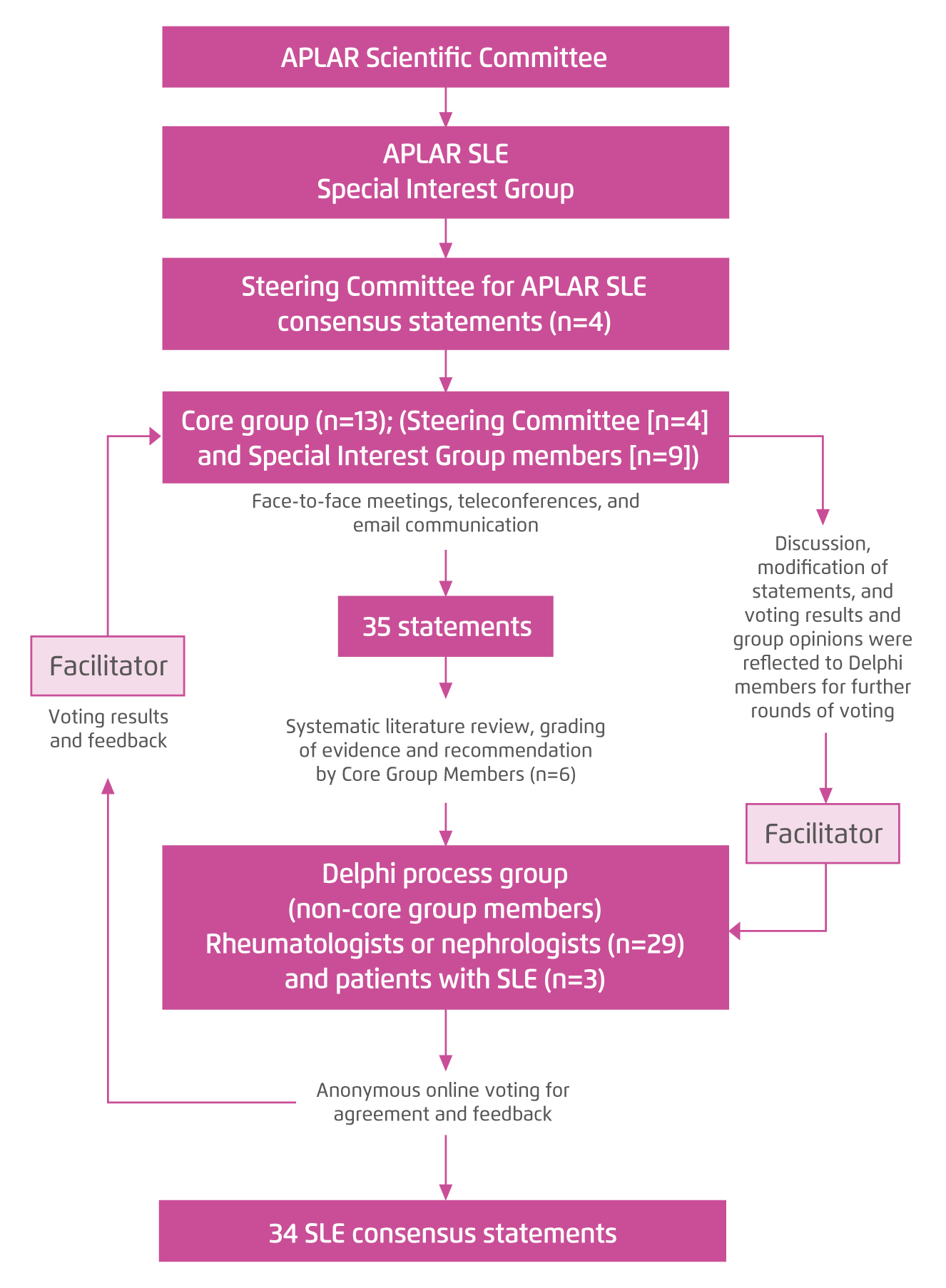

The consensus statements on management of SLE for Asia-Pacific region were formulated by the SLE special interest group (SIG) established under the Scientific Committee of the APLAR. A steering committee of 4 members, who were key opinion leaders in Asia-Pacific region and nominated by the APLAR, together with 9 experts from the APLAR formed the core group responsible for drafting the statements, which were categorised into overarching principles, general management, and specific treatment strategies for SLE.

The proposed statements drafted by the core group were evaluated in a modified Delphi process by a voting group, which consisted of specialists, either rheumatologists or nephrologists who were not involved in the preparation of the statements, and SLE patient representatives invited from each of the APLAR regions. The voting members were provided with the proposed statements with reference lists, evidence grading and strength of recommendation for the statements. After evaluating the statements, the voting members were asked to participate in an anonymous voting process on the agreement of the statements. Statements with agreement by at least 80% of the voting members were considered as reaching consensus. Results of the voting and blinded qualitative feedback from voting members during each Delphi round were summarised by the individual facilitator. Statements failed to reach consensus were reviewed and revised by the core members through teleconference or email discussion. Modified statements were voted by the voting members in subsequent rounds of voting until consensus was reached for all statements (Figure 2)6.

Figure 2. Delphi process for consensus formation6

Highlights of APLAR Consensus Statements on Management of SLE in Asia-Pacific

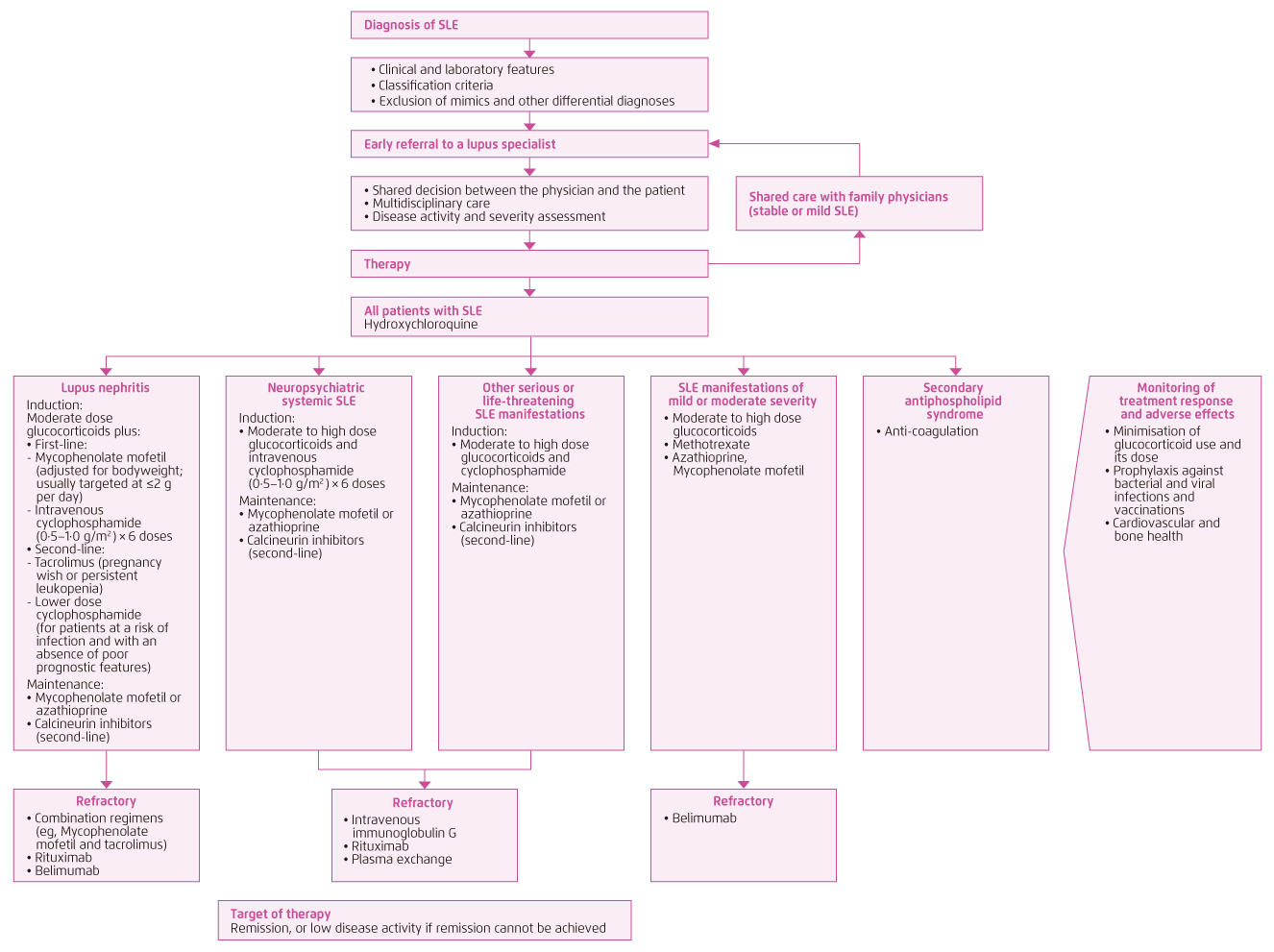

After 2 rounds of voting process, a total of 34 consensus recommendations were developed. As the overarching principles, the voting results suggested that patients with SLE should be managed by a multi-disciplinary team of lupus specialists and other health care professionals with a shared decision between physician and patient, whereas the treatment of SLE should be individualised. The panelists agreed that early diagnosis of SLE and timely referral to lupus specialists would significantly improve patients’ outcomes. The overall goals of SLE treatment are to reduce damage, ensure long-term survival and improve health-related quality of life.

In view of the general treatment strategy for SLE, the panelists generally agreed that SLE should be classified by validated criteria, such as the Systemic Lupus Collaborating Clinics20. Remission was agreed to be the goal of therapy, but when it cannot be achieved, a low disease activity state should be aimed for. Of note, disease activity should be assessed by validated disease activity indices such as the Definition of Remission in SLE (DORIS) remission criteria21. As the prevalence of renal involvement among Asian SLE patients is high, screening for renal disease is recommended. Besides, hydroxychloroquine is recommended for all Asian people with SLE.

For the management of major organ manifestations of SLE, the consensus recommendations advocated treatment with induction immunosuppression and subsequently maintenance; options include cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, and calcineurin inhibitors, in combination with glucocorticoids. For the cases of refractory or life-threatening disease, biologics, combination regimens, plasma exchange, and intravenous immunoglobulins may be considered. Anticoagulation therapy with warfarin is preferred to the direct oral anticoagulants for thromboembolic SLE manifestations associated with a high-risk antiphospholipid antibody profile (Figure 3)6. In summary, the consensus recommendations are expected to serve as a guide for specialists, general practitioners, specialty nurses and healthcare professionals who are involved in the management of SLE specialised in the Asia-Pacific region.

Figure 3. Management algorithm of SLE in Asia-Pacific region6

References

1. Zheng et al. Clin Rheumatol 2009; 28: 265-9. 2. Gordon et al. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018; 57: 1502-3. 3. Keeling et al. J. Rheumatol. 2018; 45: 1426-39. 4. Fanouriakis et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2019; 78: 736-45. 5. Assan et al. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019. DOI:10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216222. 6. Mok et al. Lancet Rheumatol 2021; 0. DOI:10.1016/s2665-9913(21)00009-6. 7. Lewis et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017; 56: i67-77. 8. Hanly et al. Arthritis Care Res 2008; 59: 721-9. 9. Zhou et al. Lupus 2008; 17: 93-9. 10. Kasitanon et al. Asian Pacific J allergy Immunol 2002; 20: 179-85. 11. Mok et al. J Rheumatol 2001; 28: 766-71. 12. Muhammed et al. Lupus 2018; 27: 688-93. 13. Pradhan et al. Rheumatol Int 2015; 35: 541-5. 14. Jakes et al. Arthritis Care Res 2012; 64: 159-68. 15. Hiraki et al. Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63: 1988-97. 16. Thong et al. Lupus 2019; 28: 334-46. 17. Kumar et al. Rheumatology 2008; 47: 690-7. 18. Helliwell et al. Rheumatology 2003; 42: 1197-201. 19. Tazi Mezalek and Bono. Medicale. 2014; 43. DOI:10.1016/j.lpm.2014.04.002. 20. Petri et al. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64: 2677-86. 21. Van Vollenhoven et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76: 554-61.