Senior Consultant Haematologist and Transplant Physician

Department of Haematology

SingHealth Duke-NUS Blood Cancer Center,

Singapore General Hospital and National Cancer,

Singapore

CLL (chronic lymphocytic leukemia) and SLL (small lymphocytic lymphoma) are of the same disease. But, in CLL cancer cells are mostly found in the blood and bone marrow; while in SLL cancer cells are mostly found in the lymph nodes. CLL/SLL belongs to a group of blood cancers known as non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).1 According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute in the United States, CLL is a disease primarily affecting older adults; the median age at diagnosis is 70 years. The age-adjusted incidence was 4.6 per 100,000 inhabitants per year. The 5-year relative survival was 65.1% in 1975 and has steadily increased over the past decades; it is estimated at 88.5% in 2024.2 Only patients with active or symptomatic disease or with advanced Binet or Rai stages require therapy. When treatment is indicated, several therapeutic options exist, including monotherapy with one of the inhibitors of Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK).2 To understand the recent development in CLL/SLL management and provide an updated guide for therapeutic decisions in daily practice, at a recent symposium in Hong Kong, Dr. Nagarajan, a renowned hematologist in Singapore, was invited to share latest research findings on CLL therapy innovations.

Due to the advancements in our understanding of CLL's pathogenesis, the management of the disease continues to experience significant and meaningful improvements. Chemoimmunotherapies have already improved overall survival when used as first-line therapy. More recently, specific inhibitors interrupting important pathways for CLL cell survival, such as BTK, have now replaced chemoimmunotherapy in first- and second-line settings.2,3

Dr. Nagarajan stated that BTK inhibitors have become a new and very active class of therapeutic agents in B-cell malignancies.4 According to Dr. Nagarajan, newer-generation BTK inhibitors have demonstrated improved safety and efficacy versus their predecessors due to key differences in their mechanism of action. For example, although ibrutinib, a first-generation BTK inhibitor, changed the treatment landscape of CLL, cardiovascular toxicity limited its use.5 Ibrutinib is generally considered as an irreversible inhibitor. However, in certain scenarios, notably with the acquisition of specific mutations like C481S, it can become reversible6. In contrast, zanubrutinib, an irreversible second-generation BTK inhibitor, is designed to maximize BTK occupancy and demonstrate less off-target kinase inhibition than ibrutinib.2,7 Complete/sustained BTK occupancy may improve efficacy outcomes and increased BTK specificity may minimize toxicities related to off-target inhibition, Dr. Nagarajan stressed.7 In addition, among the approved BTK inhibitors, zanubrutinib is less prone to pharmacokinetic modulation, leading to more consistent, sustained therapeutic exposures and enhanced dosing convenience. This can be translated into durable responses and improved safety, representing an important new treatment option for patients who benefit from BTK therapy.8

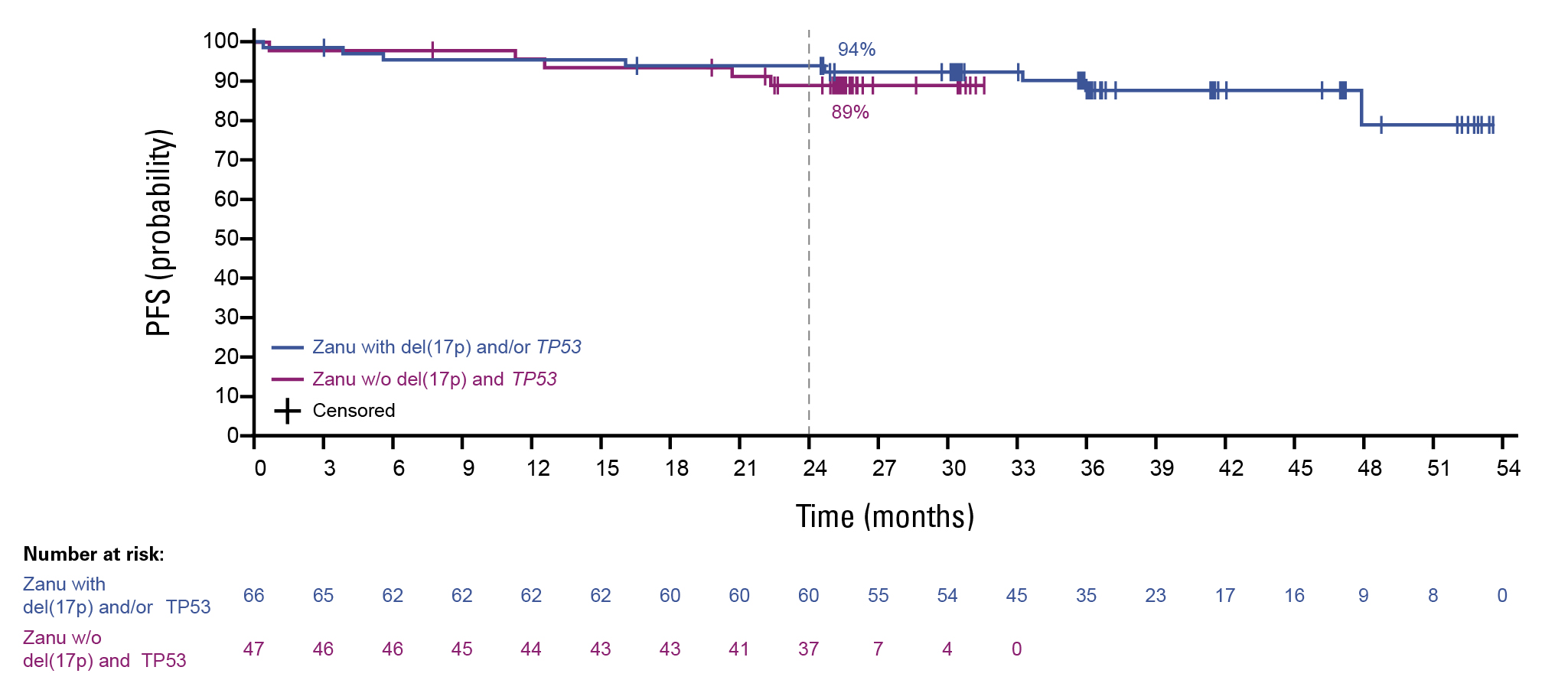

Various biological and genetic markers provide additional prognostic information. Deletions of the short arm of chromosome 17 — del(17p) and/or mutations of the TP53 gene predict a shorter time to progression with most targeted therapies.2 Among CLL patients with a del(17p), a TP53 mutation, or both, those treated with zanubrutinib demonstrated longer progression-free survival (PFS) compared to those receiving ibrutinib.9 Furthermore, in the Arm D of the SEQUOIA study (where treatment-naïve patients with CLL/SLL received zanubrutinib from cycle 1 and venetoclax from cycle 4 [ramp-up] to cycle 28, followed by continuous zanubrutinib monotherapy until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or meeting undetectable minimal residual disease [uMRD]-guided stopping criteria), the 24-month PFS rate achieved in patients with the del(17p)/TP53 mutation was comparable to that in patients without.10 As a result, zanubrutinib has been recommended as a preferred regimen regardless of the del(17p)/TP53 mutation status in the first-line setting for CLL/SLL in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.11

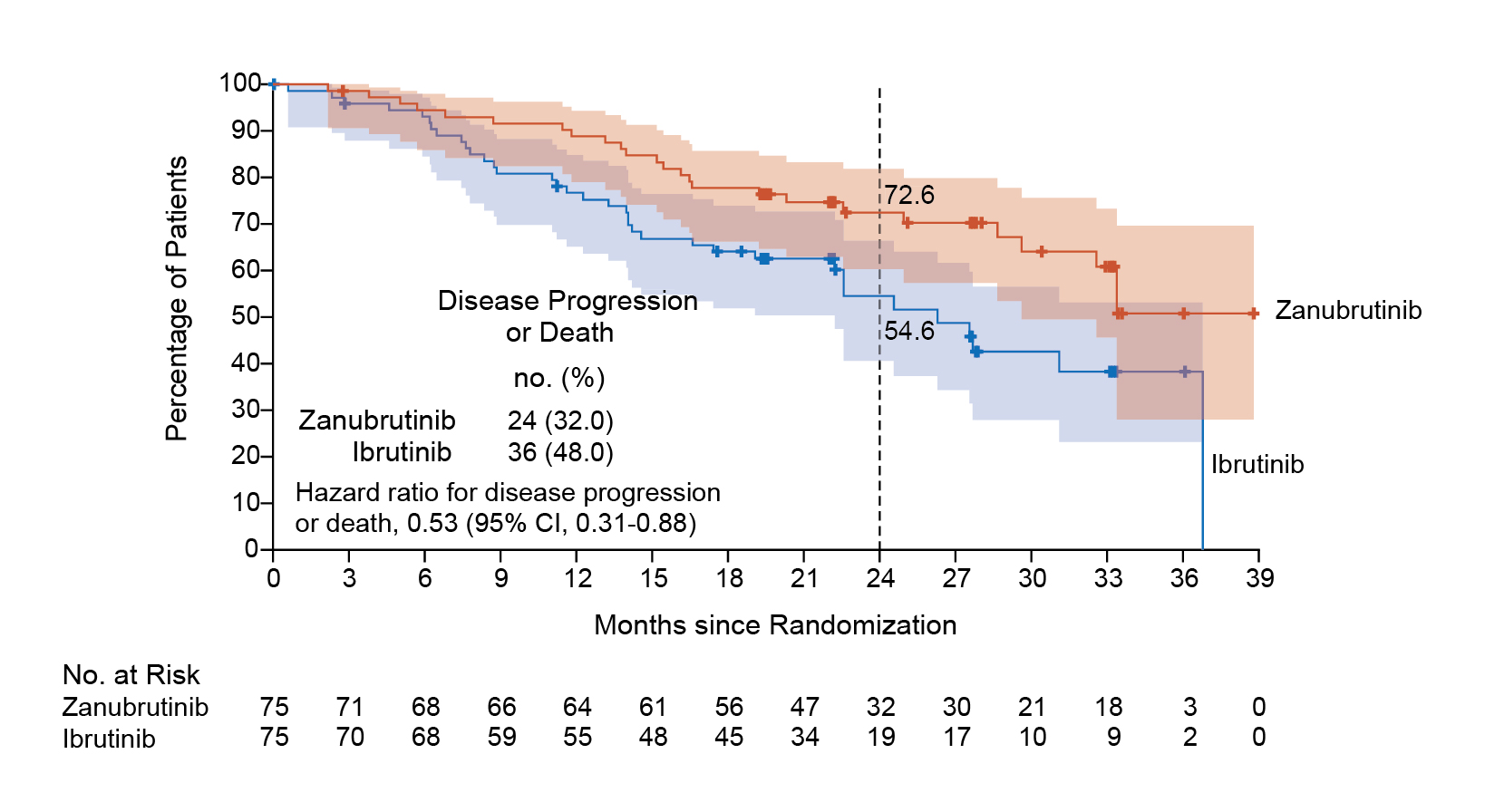

Dr. Nagarajan then presented some clinical data derived from zanubrutinib-related research. The ALPINE Phase 3 study was designed to perform a head-to-head comparison between zanubrutinib and ibrutinib in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL. After a median follow-up of 29.6 months, the results indicated that zanubrutinib was superior to ibrutinib in terms of PFS. At 24 months, the investigator-assessed PFS rates were 78.4% for zanubrutinib and 65.9% for ibrutinib; and as mentioned earlier, in patients with a del(17p), a TP53 mutation, or both, those treated with zanubrutinib demonstrated longer PFS compared to those receiving ibrutinib (Figure 1). Additionally, PFS rates consistently favored zanubrutinib across other major subgroups. The safety profile of zanubrutinib was also better than that of ibrutinib, with fewer adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation and a lower incidence of cardiac events, including those that resulted in treatment discontinuation or death.9

Figure 1: PFS in patients with a del(17p), a TP53 mutation, or both9

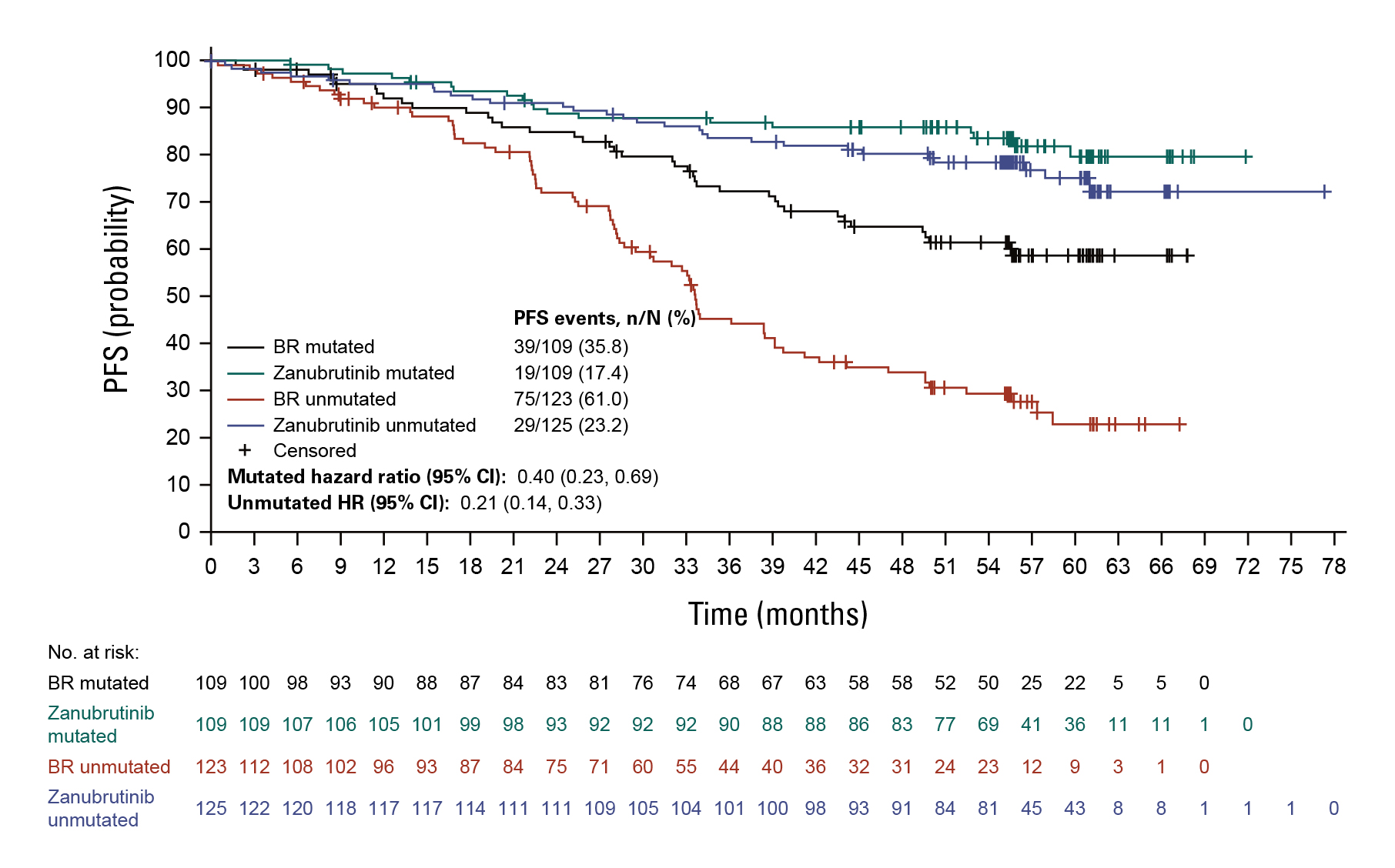

Another Phase 3 study SEQUOIA was an open-label trial that compared zanubrutinib and bendamustine plus rituximab (BR) in treatment-naïve patients with CLL/SLL. The initial prespecified analysis (median follow-up 26.2 months) and subsequent analysis (43.7 months) revealed superior PFS (primary end point) in the zanubrutinib group compared with BR. At amedian follow-up of 61.2 months, median PFS was not reached in zanubrutinib-treated patients; and median PFS was 44.1 months in BR-treated patients (hazard ratio [HR], 0.29; one-sided P = 0.0001). Prolonged PFS was observed with zanubrutinib versus BR in patients (Figure 2) with mutated immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region (IGHV) genes (HR, 0.40; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.23 to 0.69; one-sided P = 0.0003) and unmutated IGHV genes (HR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.14 to 0.33; one-sided P < 0.0001). Median overall survival (OS) was not reached in either of the treatment arms. No new safety signals were detected.12

Figure 2: PFS in patients with mutated and unmutated IGHV genes12

Also as mentioned earlier, according to a recent analysis of the Arm D of SEQUOIA (a non-randomized cohort of patients aged 65 years and older, or 18-64 years with comorbidities), regardless of del(17p)/TP53 mutational status, similar 24-month PFS rates were observed (94% in patients with TP53-aberrant disease and 89% in patients without TP53-aberrant disease), indicating the effectiveness of zanubrutinib across these genetic risk factors (Figure 3).10

Figure 3: PFS in patients with and without the del(17p)/TP53 mutation10

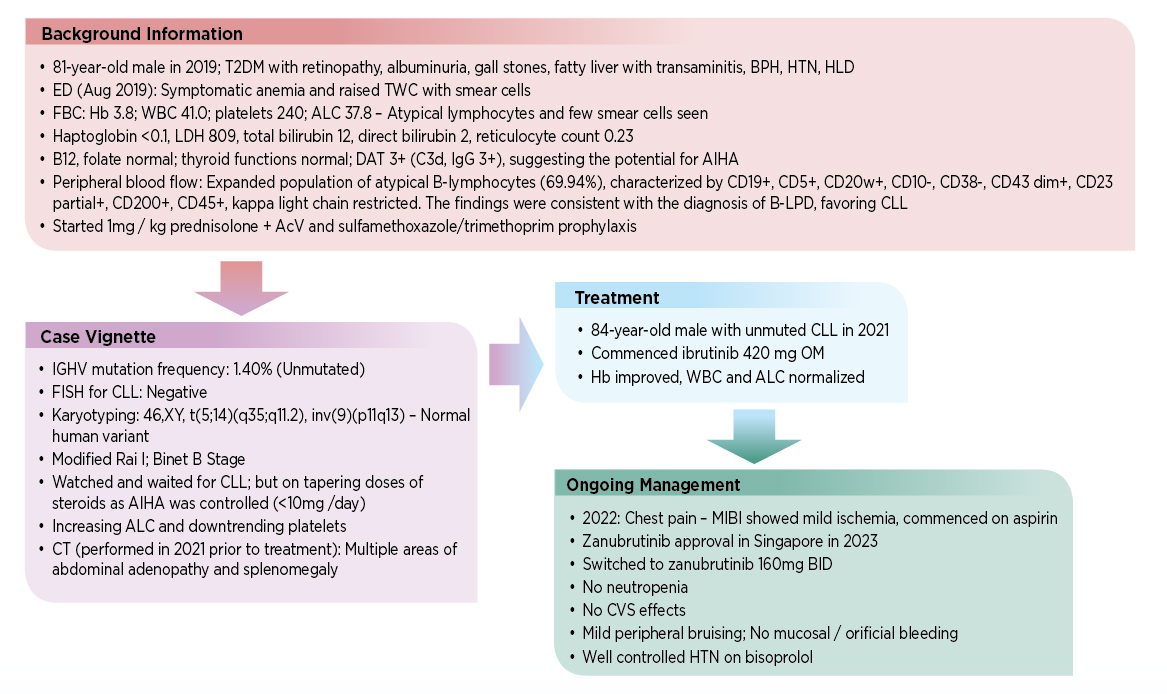

Dr. Nagarajan then presented a case to illustrate how advances in targeted therapies—specifically second-generation BTK inhibitors—were reshaping the treatment landscape for CLL.

The patient case illustrated the benefits of zanabrutinib in managing CLL, including reduced cardiotoxicity and a lower risk of major hemorrhage versus ibrutinib.7 During the discussion, Dr. Nagarajan also mentioned the challenges of using together BTK inhibitors and dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), which may increase bleeding risk, especially in patients on BTK inhibitors who also require DAPT after percutaneous coronary intervention.13

In conclusion, the management of CLL has been markedly transformed by a deeper understanding of its pathogenesis and the emergence of targeted therapies. Chemoimmunotherapy once served as the backbone of first-line treatment, but the rise of BTK inhibitors—particularly second-generation agents like zanubrutinib—has redefined clinical outcomes through improved efficacy and safety profiles. As highlighted by Dr. Nagarajan, zanubrutinib offers enhanced BTK occupancy with reduced off-target effects and pharmacokinetic variability, leading to consistent therapeutic benefits and a favorable toxicity profile. Clinical trials such as ALPINE and SEQUOIA have further validated zanubrutinib’s superiority over older therapies, including ibrutinib and BR, across diverse patient populations and genetic subtypes, including high-risk features like del(17p)/TP53 mutations. The integration of these findings into international guidelines positions zanubrutinib as a preferred first-line option, marking a significant advancement in individualized treatment and long-term disease control for untreated patients with CLL/SLL.

References

1. NIH National Cancer Institute. NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms: CLL/SLL. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/cll-sll. [Accessed 2 June 2025]. 2. Hallek M. Am J Hematol. 2025;100(3):450–80. 3. Jaglowski S and Jones JA. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2011;11(9):1379–90. 4. Wen T, et al. Leukemia. 2021; 35: 312–32. 5. Ke L, et al. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1413985. 6. Woyach JA, et al. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(24):2286–94. 7. Hillmen P, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(5):1035–45. 8. Tam CS, et al. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2021;14(11):1329–44. 9. Brown JR, et al. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(4):319–32. 10. Shadman M, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2025; 43(21):2409–17. 11. NCCN Guidelines. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma. Version 3.2025. 12. Shadman M, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43(7):780–7. 13. Mendez-Ruiz A, et al. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2023;2(3):100608.