Head, Professorial Psychiatry Unit,

Department of Psychiatry,

University of Melbourne

Australia

The disease burden of mental disorders has become increasingly relevant as this causes a high degree of individual and social suffering, whereas mood and anxiety disorders are commonly involved. Previous pooled analysis suggested that the lifetime prevalence of mood disorder reached 9.6%, and that of anxiety disorder was 12.9%1. Practically, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and pharmacological intervention are key treatments prescribed to manage mood and anxiety disorders. At the Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society for Advancement of Bipolar Affective Disorder (SABAD), which was held on 12/6/2025, Prof. Malcolm Hopwood discussed the pathophysiology of bipolar disorders and generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) and their clinical management.

Aprevious population-based survey (2003) indicated the 1-year prevalence of bipolar disorder in Australia to be about 1.0%, with a similar prevalence between males and females. The peak prevalence was observed in the age group between 18 and 24 years, accounting for 0.9%, and declined with increasing age, with the prevalence of 0.1% among adults aged >55 years2.

-01.jpg)

Figure 1. Symptomatic structure of bipolar disorder I and II3,4

Prof. Hopwood highlighted that the symptomatic structure of bipolar disorder is primarily depressive rather than manic. Notably, Judd et al. (2002) reported that patients with bipolar disorder I (BP-I) experienced 3 times more depressive symptoms (31.9% of total follow-up weeks) than manic symptoms (9.3% of weeks)3. In bipolar disorder II (BP-II), depressive symptoms (50.3% of weeks) dominated the course over hypomanic (1.3% of weeks) and cycling/mixed (2.3% of weeks) symptoms (Figure 1)4. Accordingly, a focus on the treatment for bipolar depression is needed.

Prof. Hopwood remarked that a mixed state diagnosis can be documented if a patient shows full criteria for one pole plus 3 of the symptoms of the opposing pole, according to the DSM-5 criteria. “Generally, the mixed state portrays a worse prognosis and lots of difficulties in treatment,” he commented.

Given that the poles of bipolar disorder are overlapped, Prof. Hopwood noted that the boundary between unipolar depressive disorders, bipolar, and related disorders is sometimes based only on the symptoms exhibited by the patients. In DSM-5, a series of specifiers, such as severity, clinical features, onset status, etc., was applied to define mood disorders. For instance, a mood episode may be ‘specified’ as moderate, recurrent, late-onset, with mixed features and in partial remission5. Among the clinical features specifiers of mood disorders, anxious distress is the most important feature after mixed features.

While anxiety is a comorbidity of major depressive disorder (MDD), the specifier applies to bipolar disorder as well. Essentially, patients with MDD who meet the criteria for the anxious specifier have significantly worse psychosocial functioning across a number of areas (Figure 2)6. Prof. Hopwood added that persistent anxious distress is strongly predictive of treatment resistance and a higher risk of subsequent relapse.

-10.jpg)

Figure 2. Impact of the anxious distress specifier on psychosocial functioning in patients with MDD6 , *p<0.001

In bipolar disorders, a previous review of meta-analyses suggested that at least half of those with bipolar disorder are likely to develop an anxiety disorder in their lifetimes, and a third of them will manifest an anxiety disorder at any point in time, whereas comorbid anxiety disorders negatively impacted the presentation and course of bipolar disorder7. Hence, the findings suggested a high risk of comorbid anxiety among patients with bipolar disorders, which may lead to suboptimal outcomes.

Prof. Hopwood noted that the psychological interventions can also be applied to anxiety disorder. Lifestyle interventions, such as physical exercises and regular sleep cycles, are beneficial for patients with bipolar disorder.

Prof. Hopwood highlighted that the 2 best psychotherapies in terms of research base are CBT and interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT). CBT focuses on cognitive restructuring and includes self-monitoring, strategies to deal with dysfunctional thoughts, and behavioural techniques to promote social functioning. Clinical trials showed that CBT increased functioning and adherence and decreased relapses, mood fluctuations, need for medications, and hospitalisations in bipolar patients compared with standard treatments8.

In contrast, IPSRT focuses on one of four problem areas, i.e. grief, interpersonal role transition, role dispute and interpersonal deficits, but extends into meticulous regulation of social and sleep rhythms8. Frank et al. (2005) reported that IPSRT led to a longer time to new affective episode, more regular social rhythms, and a reduced recurrence in patients with BP-I9.

In the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines 2018, recommended pharmacological treatments include acute mania, prevention of any mood episode, prevention of mania, prevention of depression, and acute depression10. Prof. Hopwood commented that the classification may not be helpful since a patient with bipolar disorder would need a choice covering all of the indications.

Prof. Hopwood presented the recommendations for bipolar depression of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP). Briefly, 6 options of monotherapy and 4 combination treatments are included (Figure 3)5. Prof. Hopwood emphasised that, provided bipolar disorder is a lifelong condition, the balance between efficacy and tolerability has to be considered in selecting treatment. He opined that although Olanzapine is effective in controlling bipolar depression, its side effects, such as weight gain, are a concern. According to the RANZCP guidelines, Quetiapine is the most favoured second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) for bipolar depression in clinical practice, whereas lamotrigine is the preferred mood stabilising agent (MSA)5.

-19.jpg)

Figure 3. Effectiveness of medications used to treat bipolar depression in RANZCP 5

Prof. Hopwood commented that the introduction of atypical antipsychotics into both bipolar depression management and maintenance has been one of the changes over the recent 2 decades. In particular, Quetiapine is the therapy with the largest amount of evidence support in bipolar depression.

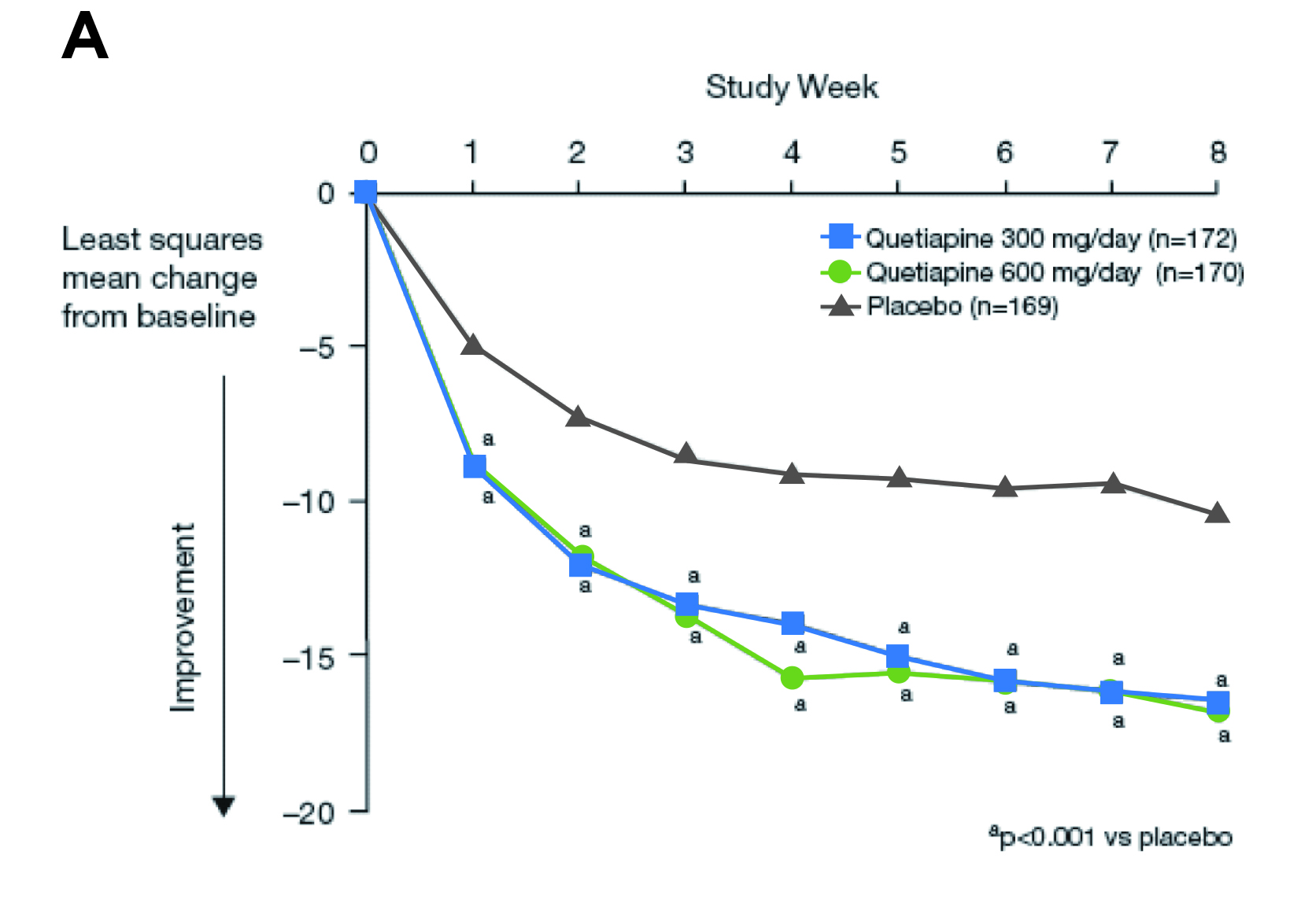

The landmark trials demonstrating the efficacy of Quetiapine in managing bipolar depression are the BOLDER I & II trials. In the BOLDER I trial, patients meeting DSM-4 criteria for bipolar I (n=360) or bipolar II (n=182) depression were randomly assigned to 8 weeks of Quetiapine (600 or 300 mg/day) or placebo. The results demonstrated that Quetiapine at either dose achieved significant improvement in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total scores compared with placebo from week 1 onward (Figure 4A)11. While bipolar with a rapid cycling course is a clinical challenge, an 8-week Quetiapine treatment, both 600 and 300 mg/day, was shown to significantly improve MADRS score in bipolar patients, regardless of rapid cycling courses, in the BOLDER II trial (Figure 4B)12,13.

Figure 4. Improvement in MADRS total score yielded in A) BOLDER I and B) BOLDER II trials11,13

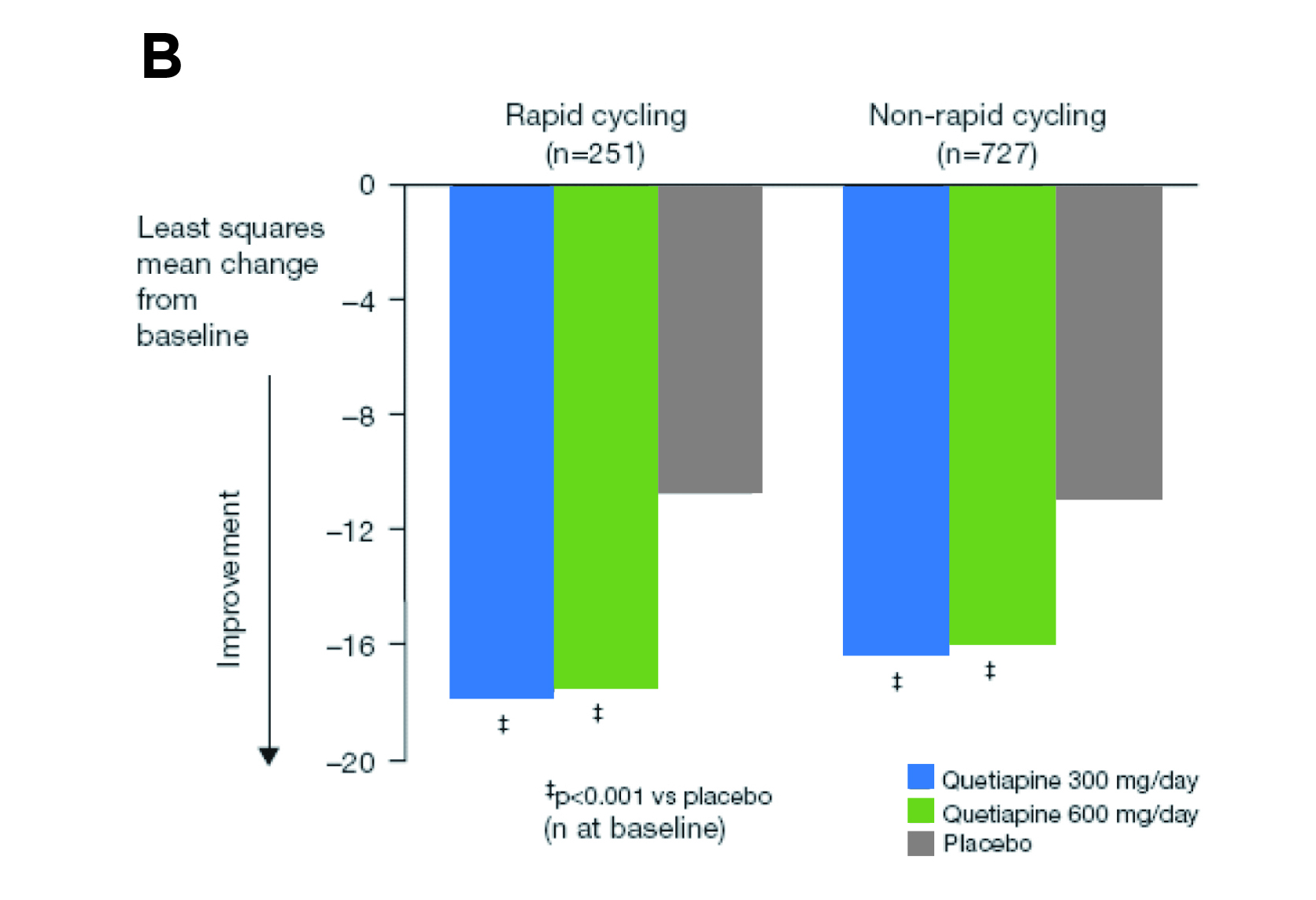

Furthermore, the long-term efficacy of Quetiapine was demonstrated in the 52-week continuation phase study of the EMBOLDEN trial. Responders in the EMBOLDEN I & II trials (n=584) were randomised to the same Quetiapine dose or placebo for 26-52 weeks or until mood event recurrence. The results indicated that the risk of recurrence of a mood event was significantly lower with Quetiapine than with placebo (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.51, p<0.001, Figure 5). Also, Quetiapine was associated with a lower risk for recurrence of depressive events (HR: 0.43, p<0.001). Discontinuation rates due to adverse events were 4.3%, 4.0% and 1.7% for Quetiapine 300 mg/day, 600 mg/day and placebo, respectively14.

Figure 5. Time to recurrence of any mood event in the continuation phase14

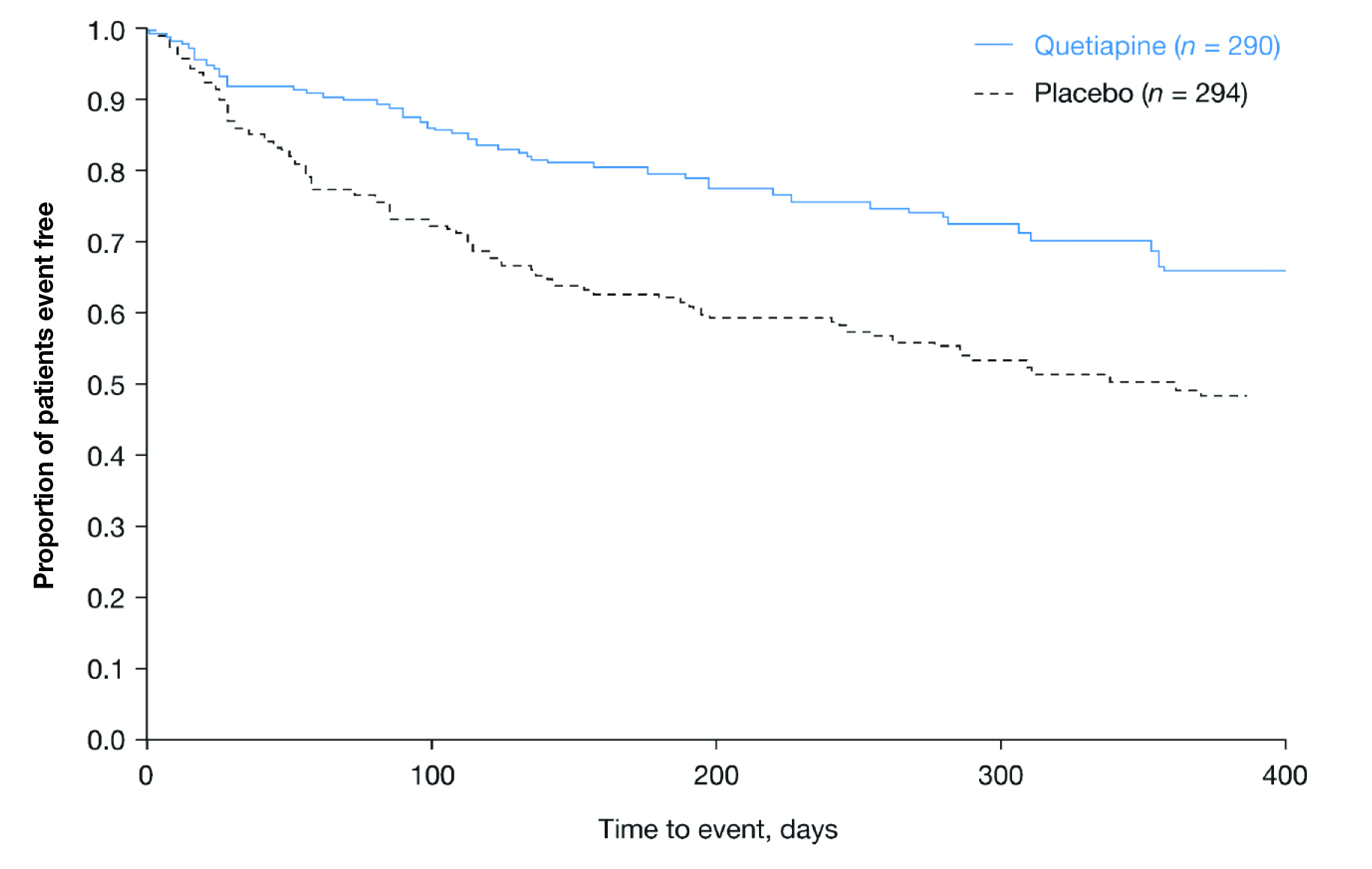

Prof. Hopwood presented the findings of a meta-analysis conducted by his team (2018) comparing the responder rates of Lurasidone, Quetiapine, and Cariprazine monotherapy with those of Olanzapine/Fluoxetine combination (OFC) therapy. The MADRS responder rates for Lurasidone, Quetiapine, Cariprazinem and OFC were 52.0%, 59.7%, 46.3%, and 56.1%, respectively. Prof. Hopwood noted that the responder rates of the placebo group in the studies of Quetiapine (41.1%) were higher than those in other studies, which ranged from 30.2% to 35.9% (Figure 6). Thus, Quetiapine yielded the best response among the therapies.

Figure 6. The MADRS responder rates of different therapies , LUR: Lurasidone, QUE: Quetiapine, CAR: Cariprazinem, PBO: placebo, NNT: number needed to treat, CI: confidence interval

Prof. Hopwood highlighted that one of the most significant unmet needs in bipolar disorders is anxiety. The combined lifetime prevalence of DSM-5 GAD among the general population was 3.7%, the 12-month prevalence was 1.8%, and the 30-day prevalence was 0.8%15. GAD also causes significant functional disabilities. For instance, an analysis of patient survey data in Europe by Toghanian et al. (2014), involving >3,500 patients with GAD, reported that when compared with matched controls, patients with GAD were significantly more likely to visit healthcare providers, receive a higher number of total medications, and reduce work productivity. Moreover, the direct and indirect healthcare costs associated with GAD were substantial16.

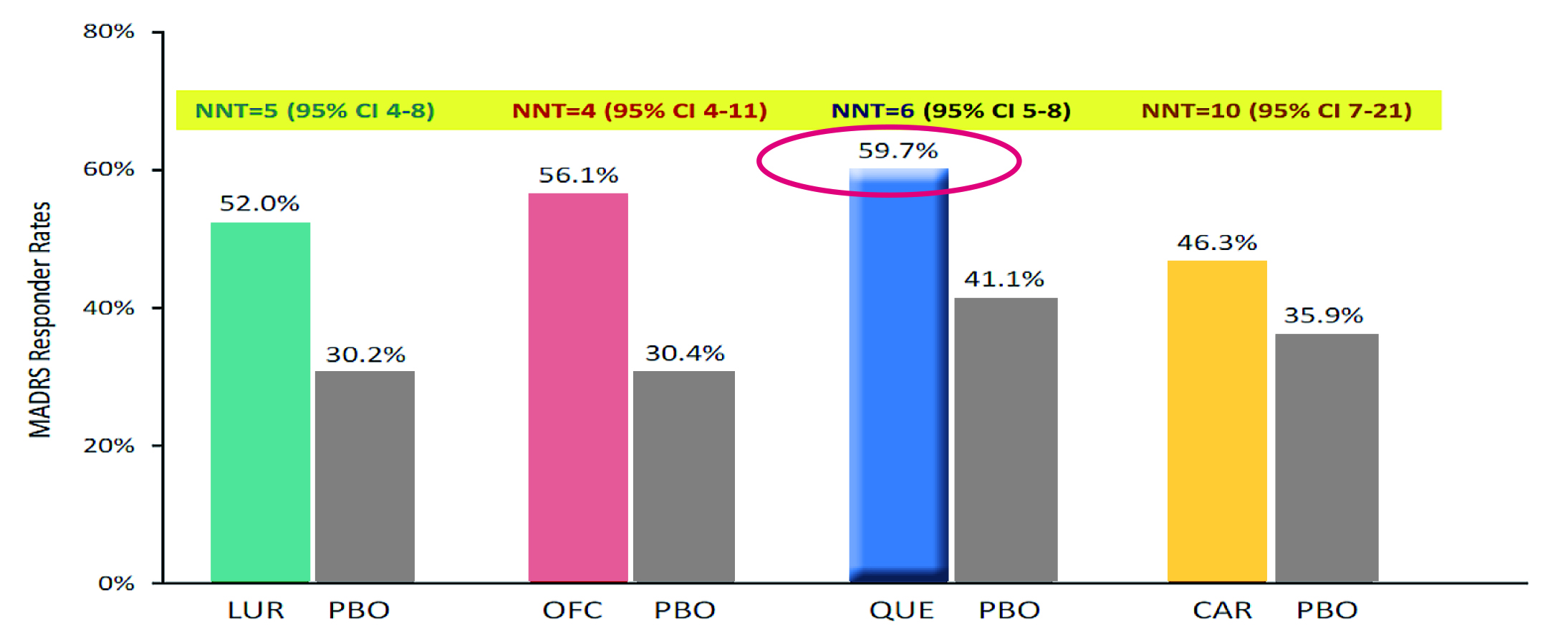

Prof. Hopwood noted that there is very little clinical data about antipsychotics in GAD, but it does not imply the use of antipsychotics in the disease is uncommon. In the case of Quetiapine, a meta-analysis of 4 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in 2010, involving 1,369 patients treated with Quetiapine, revealed that Quetiapine monotherapy yielded a significantly higher response than placebo (odds ratio [OR]: 2.21, p=0.03). Essentially, there was a significant difference in remission, as defined as a HAM-A total score of 7 or less, favouring Quetiapine monotherapy (OR: 1.83, p=0.03, Figure 7). Moreover, the study reported that the risk of recurrence of anxiety symptoms was significantly higher in the placebo group as compared to Quetiapine group (OR: 0.18)17.

-34.jpg)

Figure 7. Forest plot of comparison between Quetiapine monotherapy and placebo in achieving remission in GAD17

More recently, the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) reported a guideline in 2023, which included a review of all therapies with evidence in treating GAD. Quetiapine was found effective as a monotherapy for GAD and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Particularly, the panel admitted that GAD is generally a chronic disorder and requires long-term treatment. Of importance, it was advocated that treatment should continue for at least several months after remission to prevent relapse. In this regard, Quetiapine was one of the recommended therapies which was demonstrated to be more effective than placebo in preventing relapse18.

Although there are limited RCTs to evaluate treatment efficacy in older patients, the WFSBP guideline found that Quetiapine was effective in older patients with GAD. Given that Quetiapine monotherapy was confirmed to be efficacious in treating GAD, the WFSBP concluded that Quetiapine should be included in the recommended treatments for GAD, whereas low doses (50-300mg/day) would be suitable18.

Undoubtedly, bipolar disorder is a prevalent psychiatric disorder with a significant disease burden to patients, their families, and society, whereas the disease with comorbid anxiety is a more challenging clinical condition. Fortunately, based on the existing clinical data, various therapies have been demonstrated to be effective in managing the disease. Remarkably, Quetiapine has been indicated as a preferable therapy in bipolar depression, which balances efficacy and tolerability. While the occurrence of GAD is an unmet need in bipolar disorder, Prof. Hopwood suggested that Quetiapine may be useful in that condition, either as monotherapy or in combination with other agents by virtue of the established evidence.

BP I=bipolar disorder I; BP II=bipolar disorder II; CANMAT=Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments; CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy; DSM-5=Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition; GAD=generalised anxiety disorder; HR=hazard ratio; IPSRT=interpersonal and social rhythm therapy; MDD=major depressive disorder; MSA=mood stabilising agent; OFC=olanzapine fluoxetine combination; OR=odds ratio; PTSD=post-traumatic stress disorder; RANZCP= Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists; RCT=randomised controlled trial; SABAD=Society for Advancement of Bipolar Affective Disorder; SGA=second-generation antipsychotics; WFSBP= World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry

References

1. Steel et al. Int J Epidemiol 2014; 43: 476–93. 2. Mitchell al. Psychol Med 2004; 34: 777–85. 3. Judd et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59: 530–7. 4. Judd et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60: 261–9. 5. Malhi et al. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2015; 49: 1087–206. 6. Hopwood. Neurol Ther 2023; 12: 5–12. 7. Spoorthy et al. World J Psychiatry 2019; 9: 7-29. 8. Yatham et al. Bipolar Disord 2005; 7: 5–69. 9. Frank et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62: 996–1004. 10. Yatham et al. Bipolar Disord 2018; 20: 97-170. 11. Calabrese et al. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 1351–60. 12. Thase et al. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006; 26: 600–9. 13. Thase ME. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2008;4(1):21–31. 14. Young et al. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 2014; 15: 96–112. 15. Ruscio et al. JAMA Psychiatry 2017; 74: 465–75. 16. Toghanian et al. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2014; 6: 151-63. 17. Depping et al. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010; published online Dec 8. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD008120.PUB2. 18. Bandelow et al. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 2023; 24: 79–117.

Please scan or click the QR code for the video highlight.