Distinguished Professor of Medicine and Rheumatology

President-Elect, Osteoarthritis Research Society International

Inaugural Director, Center for Musculoskeletal Health

UC Davis Health

Sacramento, CA, USA

Joint disease is frequently observed in primary care settings, with osteoarthritis (OA) being the most common condition1. OA is a disorder involving movable joints that as physiologic derangements (characterised by cartilage degradation, bone remodelling, osteophyte formation, joint inflammation and loss of normal joint function), that can culminate in illness2. While any joint can be affected, OA is more prevalent in knee, hip, spine, and interphalangeal joints3. Apart from pain and limited joint function, joint disorders significantly impair the patient’s quality of life (QoL) as well3. Clinically, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches are available for managing OA. Provided the safety concerns associated with long-term pharmacological treatments4, there is ongoing interest in identifying alternative products that safely promote joint health and improve joint disorder symptoms. Accordingly, emerging evidence advocates that oral supplementation of undenatured type II collagen (UCII) is effective in controlling some joint disorders.

OA is the most common form of arthritis. It has been reported that joint injury (including sport injury), congenital bone shape, repetitive use, and load bearing at work are risk factors of OA hip, whereas obesity, joint injury, and kneeling and squatting at work are associated with OA knee5. Aging also increases the risk of OA6. The global prevalence of OA among people aged ≥65 years was estimated to be 7.4% in 2005 but was projected to be 16.1% in 2050. In Hong Kong, the prevalence was expected to rise from 12% to 32.3% in the same period7. A previous local survey by Cheung et al. (2017) suggested that joint pain constituted 45.5% of reported chronic pain8.

Apart from aging, female gender is a risk factor of OA as well. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 73% of people living with OA are older than 55 years, and 60% are female9. The prevalence of OA knee was 13% in Chinese women and 5% in Chinese men5. Besides, Zhang et al. (2001) revealed a racial difference in OA prevalence that the prevalence of radiographic and symptomatic OA knee in Chinese men was similar to that in Caucasian men but was significantly higher among Chinese women than Caucasian women10.

Existing literature typically evaluates the disease burden of joint disorders in individual and socioeconomic aspects, respectively. Regarding the physiological impact of OA, pain and limited joint function are particularly concerning to the patients. Given OA is a disease that does not resolve, patients may live with persistent and potentially intense pain11. In addition, OA is associated with adverse consequences in mood and QoL. It is noteworthy that about 70% of older OA patients suffer from poor sleep quality, which is thus linked to fatigue. Importantly, OA further contributes to significant indirect costs attributed to productivity loss, premature death, and early retirement11. In addition to the adverse impacts on individual patients, the socioeconomic costs associated with OA are also significant3.

Even though the disease burden of OA is substantial, there are currently no approved disease-modifying medications for the disease, and there are safety concerns with the prolonged use of specific treatments against OA symptoms. Notably, a systematic review of 25 International clinical practice guidelines by Gibbs et al. (2023) suggested that higher-quality guidelines for hip and knee OA consistently recommended the implementation of exercise, education, and weight management, alongside consideration of pharmacological management12.

Given the goal of OA treatment is to reduce pain intensity and improve function and QoL, the Hong Kong College of Orthopaedic Surgeons (HKCOS) and various international clinical guidelines recommended topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (topical NSAIDs) and paracetamol as the first-line pharmacological treatments for mild to moderate OA pain because of its efficacy and safety, while oral NSAIDs are recommended as the second-line13. There are published opinions highlighting the risk of cardiovascular (CV), gastrointestinal (GI) and renal adverse events (AEs) associated with the application of oral NSAIDs. Accordingly, topical NSAIDs are usually preferred over oral treatments for safety reasons14.

In addition to topical NSAIDs, various oral supplements have been developed and positioned to support a preventive or therapeutic effect in patients with OA. Glucosamine and chondroitin are commonly oral supplements used by patients with OA. A systematic review including 15 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) by Vo et al. (2023) demonstrated that oral glucosamine significantly decreased global pain as compared to placebo. However, insufficient effects were observed in Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) score15. Similarly, clinical data on chondroitin’s efficacy in controlling OA are inconsistent16.

Due to the inconsistent and inadequate clinical evidence regarding glucosamine and chondroitin in managing OA, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines of the United Kingdom (UK) addressed that glucosamine and chondroitin should not be prescribed to treat OA17.

Curcumin, a polyphenolic compound extracted from turmeric, is widely used in traditional Chinese medicine to treat OA. A meta-analysis by Zeng et al. (2022) suggested that curcumin and curcuma longa extract had no safety signals in any of the studies and improved the severity of inflammation and pain levels in arthritis patients. Nonetheless, the report remarked that findings need to be interpreted carefully due to the low quality and small quantity of RCTs included18.

Besides, other ingredients, such as methylsulfonylmethane (MSM)19, omega-3 fatty acids20, and frankincense21, have been reported to be effective to relieve pain and improve joint function in healthy subjects or patients with OA. However, further clinical evidence is required to confirm their efficacy and safety profile.

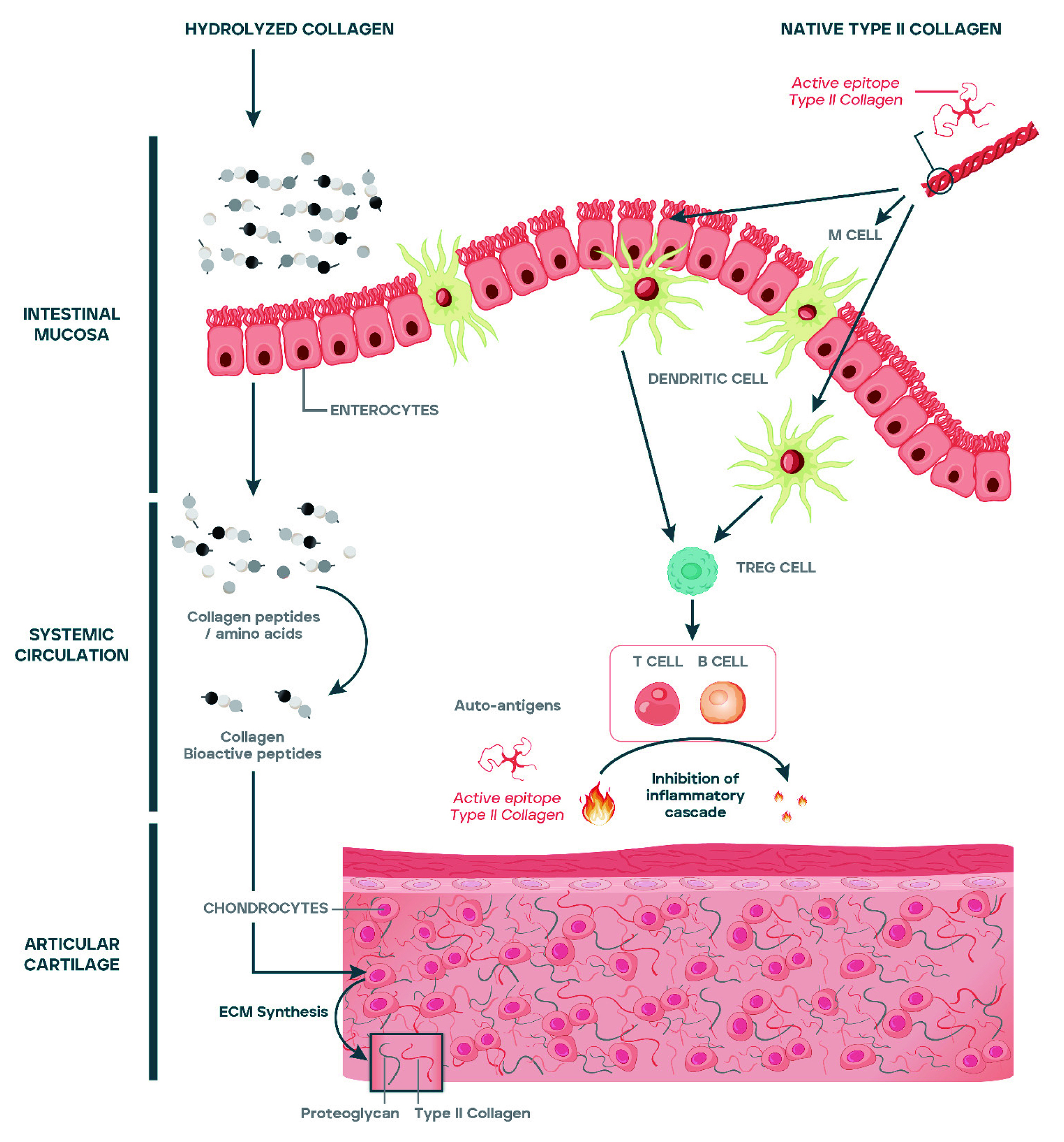

Collagen is the most abundant protein in the extracellular matrix (ECM) and connective tissues of vertebrates. Based on their structure, supramolecular organisation, and functional features, 28 types of collagens have been described. Particularly, type-II collagen is the primary constituent of articular cartilage, which protects against wear and tear associated with joint mobilisation and movement. Interestingly, undenatured type-II collagen, also known as native type-II collagen or UCII, is type-II collagen that has not been broken down by heat, acids or enzymes, and has been reported to elicit an immune-mediated response called oral tolerance3. Importantly, UCII is different from hydrolysed collagen (collagen peptides, collagen hydrolysate, or HCII), which is digested and absorbed in body3.

The theory on the mechanism of action is the following. Upon oral consumption, the luminal antigens of UCII are captured by antigen-presenting cells, which then migrate into gut-draining mesenteric lymph nodes where they initiate activation and differentiation of regulatory T cells (TREG). It is hypothesised that the TREG cells may migrate through the circulation. When TREG cells recognise type II collagen in joint cartilage, they secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines, including transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), interleukin 4 (IL-4) and interleukin 10 (IL-10), to help reduce joint inflammation and promotes cartilage repair (Figure 1)3. Studies to confirm this hypothesis have not yet been performed.

Figure 1: Proposed Inhibition of inflammation cascade at articular cartilage by UCII3

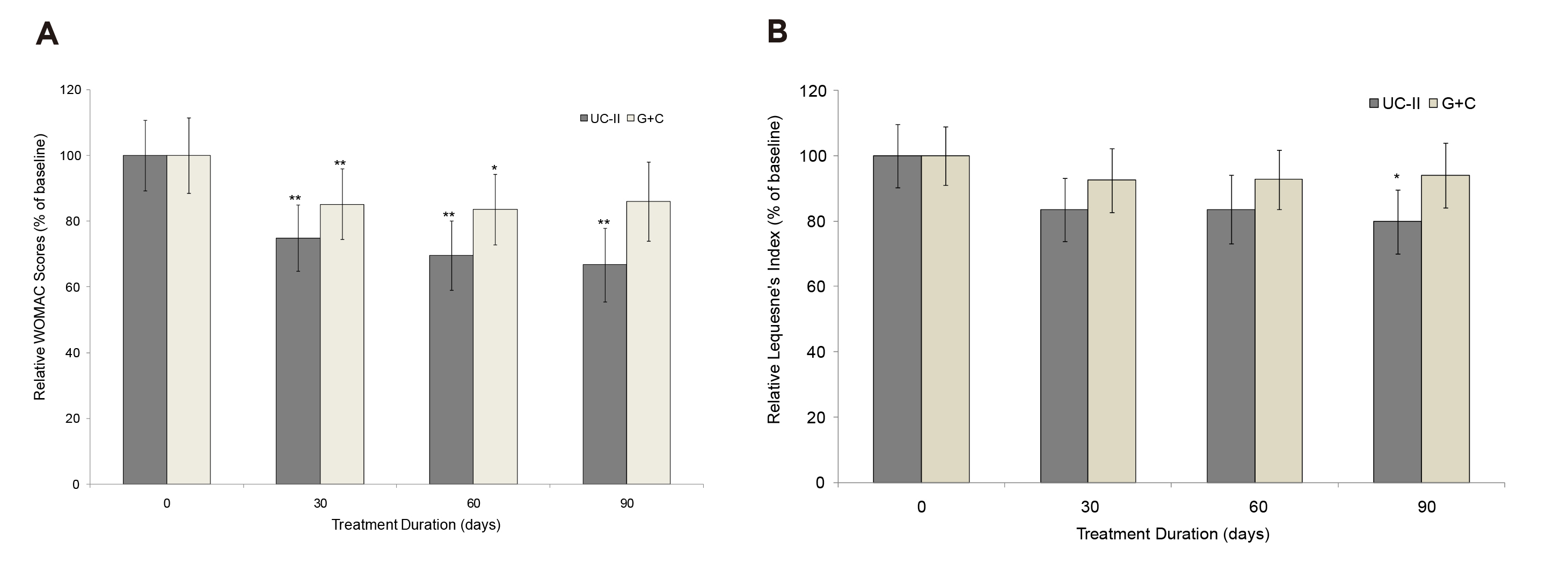

The landmark trial demonstrating the clinical benefits of UCII against OA was conducted by Crowley et al. (2009). In the trial, 52 patients with OA were randomly assigned to receive oral supplementation with either 40mg UCII (n=26) or glucosamine plus chondroitin (G+C, n=26). The effects of UCII in reducing pain were observed since the first follow-up on Day 30 (Figure 2A). After 90 days of treatment, UCII yielded significant improvements in all assessments. Essentially, greater reductions in WOMAC score (33% [UCII] vs 14% [G+C], Figure 2A), VAS score (40% [UCII] vs 15.4% [G+C]), and Lequesne’s functional index (20% [UCII] vs 6% [G+C], Figure 2B) were observed in UCII against G+C22. The results implied that UCII supplementation was effective in countering OA-related pain than G+C and improving the patient's QoL.

Figure 2: Changes in A) WOMAC score and B) Lequesne’s functional index at Day 90 from baseline22, *p<0.05, **p<0.005 indicate significantly different from baseline

A clinical study involving 30 patients with OA knee by Yaremenko et al. (2021) indicated that oral treatment with 40mg UCII significantly decreased Leken and WOMAC score by 5.3% and 9.1%, respectively, in 4 weeks. At the endpoint, significant improvements of 25% in Leken index and 33.1% in WOMAC score were observed. Also, there was a significant decrease in uCTX-II (product of destruction of collagen type II) concentration by 5.6% at 12 weeks. The results suggested that UCII supplementation was effective in improving the clinical manifestations and metabolic disorders of cartilage in knee OA patients, with a good safety profile.

The results were confirmed by the recent meta-analysis by Kumar et al. (2023), which included 8 RCTs, accounting for 243 patients with early OA. After the mean follow-up of 3-6 months, significantly better WOMAC (pooled mean difference: -8.91, p=0.0003) and VAS (pooled mean difference: -1.65, p=0.004) scores were obtained with UCII compared to placebo. With UCII, walking measurements improved significantly from the baseline, reflected in improved timed up-and-go and 6-minute walk tests (6MWT)23. As per existing literature, UCII has shown promise as a potent supplement in early knee OA with good pain relief and improved function.

Apart from improving OA symptoms, UCII was shown to be beneficial in the healthy population as well. Remarkably, the RCT involving 55 healthy participants who experienced joint discomfort with physical activity by Lugo et al. (2013) indicated that 120-day 40 mg UCII supplementation resulted in a statistically significant improvement in average knee extension compared to placebo (81.0±1.3º vs 74.0±2.2º, p=0.011) and to baseline (81.0±1.3º vs 73.2±1.9º, p=0.002, Figure 3). Importantly, the results further reported that the UCII group exercised longer before experiencing any initial joint discomfort at day 120 (2.8±0.5 min, p=0.019) compared to baseline (1.4±0.2 min)24. No UCII-related adverse events were observed during the study. Therefore, the results suggested that UCII would improve knee joint extension in healthy subjects and potentially alleviate joint pain arising from physical activities.

for joint support-8.jpg)

Figure 3: Improved knee extension upon UC-II supplementation24, *p≤0.05: significant difference versus baseline or placebo

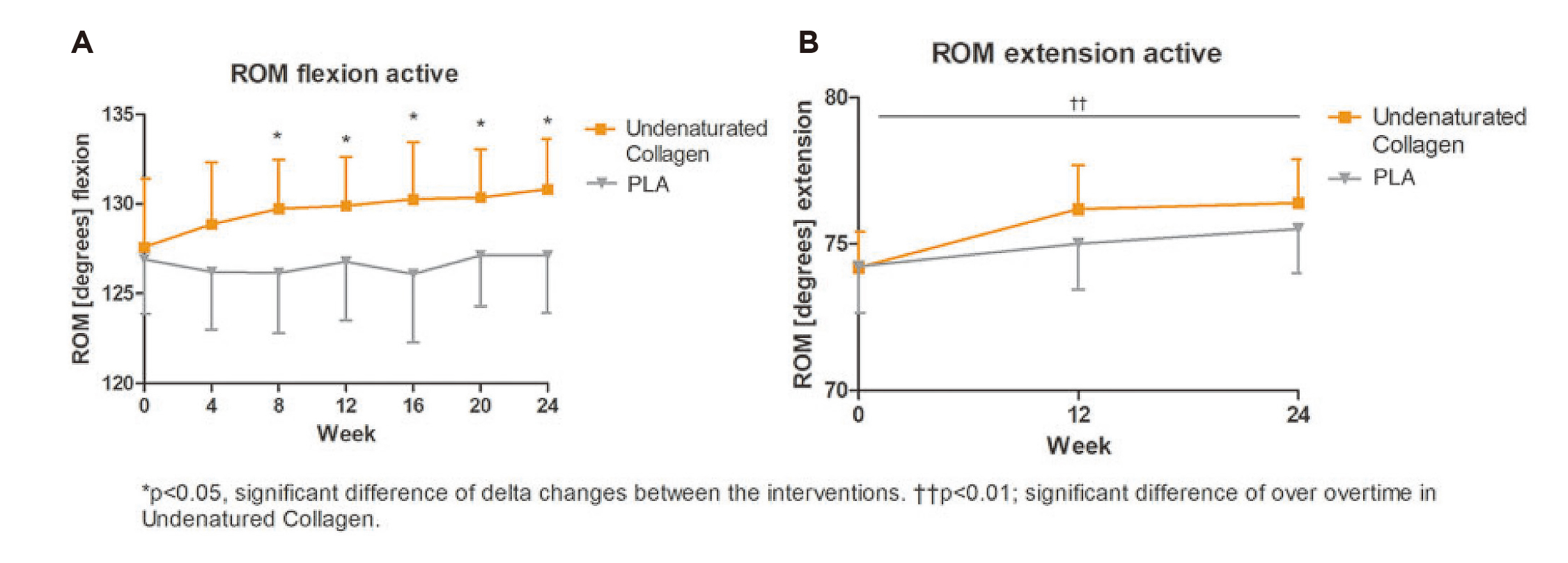

More recently, the RCT by Schon et al. (2022), which recruited 96 healthy subjects with activity-related joint discomfort, reported that 24 weeks of daily UCII supplementation significantly increased knee range of motion (ROM) flexion (3.23º vs 0.21º, p=0.025) and extension (2.21º vs 1.27º, p=0.0061) versus placebo (Figure 4A and 4B)25. Thus, daily UCII supplementation improved knee joint ROM flexibility and extensibility in healthy subjects with activity-related joint discomfort. UCII showed increasing knee extension in healthy adults and preventing them from developing more serious joint problems, implying potential ease the ageing burden from public health perspectives.

Figure 4: Improvements in ROM flexion and extension25

With the aging local population, the prevalence of OA is expected to increase and providing the best possible evidence-based management of the disease is thus of paramount importance.

The outcomes of UCII supplementation in managing rheumatoid arthritis (RA) had been investigated. There were two multicentre, double-blinded RCTs comparing UCII and methotrexate (MTX) respectively by Zhang et al. (2008), which involved 236 RA patients, and Wei et al. (2009), involving 454 RA patients, showed that UCII was effective in controlling RA symptoms, with significantly less side effects than MTX26,27. However, today, effective anti-cytokine therapies are used and both treat active RA and reduce joint destruction.

In summary, oral supplementation with UCII appears to be effective in reducing pain and improving joint function in patients with OA comparing with placebo or G+C, with preferable tolerability. Moreover, clinical data suggested that the efficacy of UCII can be sustained over a prolonged period. Hence, the possibility of recommending UCII oral supplementation in clinical guidelines is worth considering. Besides countering OA symptoms, the potential benefits of UCII in healthy individuals with exercise-induced knee pain are noteworthy and should be a safe option for patients with these medical aliments.

References

1. Henrotin et al. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2018; 20. DOI:10.1007/S11926-018-0782-9. 2. Osteoarthritis Research Society International. Standardization of Osteoarthritis Definitions. 2025. https://oarsi.org/research/standardization-osteoarthritis-definitions (accessed May 16, 2025). 3. Martínez-Puig et al. Nutrients 2023, Vol 15, Page 1332 2023; 15: 1332. 4. Curtis et al. Drugs Aging 2019; 36: 25. 5. Lau et al. Hong Kong Medical Journal 2007; 13: 9–14. 6. O’Brien et al. Mech Ageing Dev 2019; 180: 21–8. 7. Lee et al. Aust Fam Physician 2008; 37: 874–7. 8. Cheung et al. Pain Practice 2017; 17: 643–54. 9. World Health Organization. Osteoarthritis. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/osteoarthritis/ (accessed May 12, 2025). 10. Zhang et al. Arthritis Rheum 2001; 44: 2065–71. 11. Hunter et al. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2014; 10: 437–41. 12. Gibbs et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2023; 31: 1280–92. 13. Yau et al. The Hong Kong College of Orthopaedic Surgeons Position Statement in Management of Osteoarthritis of Knee. 2022 DOI:https://www.hkcos.org.hk/Position_Statement/HKCOS_Position_Statement_in_Management_of_Osteoarthrit is_of_Knee.pdf. 14. Magni et al. Pain Ther 2021; 10: 783. 15. Vo et al. Pharmacy (Basel) 2023; 11: 117. 16. Brito et al. Cureus 2023; 15. DOI:10.7759/CUREUS.40192. 17. NHS. Glucosamine and Chondroitin Patient Information Leaflet. https://www.hweclinicalguidance.nhs.uk/prescribing-guidance/glucosamine-and-chondroitin-patient-information-leaflet/ (accessed April 1, 2025). 18. Zeng et al. Front Immunol 2022; 13. DOI:10.3389/FIMMU.2022.891822/PDF. 19. Toguchi et al. Nutrients 2023; 15: 2995. 20. Deng et al. J Orthop Surg Res 2023; 18. DOI:10.1186/S13018-023-03855-W,. 21. Mohsenzadeh et al. BMC Res Notes 2023; 16. DOI:10.1186/S13104-023-06291-5. 22. Crowley et al. Int J Med Sci 2009; 6: 312–21. 23. Kumar et al. Am J Transl Res 2023; 15: 5545. 24. Lugo et al. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2013; 10. DOI:10.1186/1550-2783-10-48. 25. Schön et al. Journal of integrative and complementary medicine 2022; 28: 540–8. 26. Zhang et al. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2008; 59: 905–10. 27. Wei et al. Arthritis Res Ther 2009; 11. DOI:10.1186/AR2870.