Specialist in Cardiology

The elevation of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is a key aspect of dyslipidaemia and is associated with an increased cardiovascular risk, especially in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). While numerous studies advocate the pivotal roles of LDL-C as the primary driving force of atherosclerosis progression, lowering LDL-C level has been the mainstay strategy for preventing ASCVD and related complications1. Currently, statins are the cornerstone of lipid-lowering therapy. However, adverse events are common with higher-intensity statin, and there remains a residual risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) even after intensive statin therapy2. Accordingly, emerging studies showed that statins combined with ezetimibe resulted in considerable efficacy, with better safety and adherence than statin intensification alone3. To uncover the essentials in managing dyslipidaemia, Dr. Kwok Chun Kit Kevin was invited to discuss the unmet needs of statin monotherapy and highlight the clinical performance of statin/ezetimibe combined therapy in controlling LDL-C levels.

Dr. Kwok noted that he defines the target of LDL-C reduction for each patient based primarily on the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) 2019 Guidelines. According to the ESC 2019 Guidelines, patients are classified into various cardiovascular (CV) risk categories, ranging from low to very high risk. The intervention strategy is decided as a function of total CV risk and baseline LDL-C level4. “In cases which a substantial LDL-C reduction is required, more intensive treatment, such as higher-intensity statins, would be prescribed,” Dr. Kwok addressed.

Existing literature generally agrees that statins are efficacious in lowering LDL-C levels, with a satisfactory safety profile5. In this regard, it is a usual practice for Dr. Kwok to prescribe moderate-intensity statins instead of low-intensity. From his observation, statin treatment reduces LDL-C levels by about 50% on average. Nonetheless, the clinical application of statins may be hindered by treatment-related adverse events, particularly liver injury6 and myalgia7. Hence, Dr. Kwok reminded that the prescribed statin dosage should not be too aggressive and that the patient’s treatment outcomes have to be monitored.

Remarkably, Dr. Kwok highlighted that the abnormalities in blood tests might not be observed soon after commencing statin treatment but develop after a prolonged period, maybe over 1 year. Moreover, the abnormalities can be attributed to various factors, including the consumption of alcohol or alternative medications by the patient. Notably, the carrier status of the patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) is noteworthy.

Apart from statin-related adverse events, previous studies reported a significant proportion of patients with high CV risk unable to achieve LDL-C target even after intensive statin therapy8. In handling patients who failed to achieve adequate LDL-C control, Dr. Kwok advised first considering patient compliance with treatment. Interestingly, he pointed out a misconception about LDL-C management among public, which suggested that further treatment is no longer needed upon achieving the LDL-C target. Thus, he emphasised the importance of patient education in enhancing compliance with treatment. Besides, it is crucial to check if the patient has missed doses or consumed any food and/or medications that interact with the statin prescribed leading to suboptimal efficacy.

Given there is no patient compliance issue, an evaluation of the current treatment dosage helps rule out under-treatment due to inadequate dosage, especially among patients requiring substantial LDL-C reduction. Increasing statin dosage should be considered if the current dosage is inadequate but well-tolerated. However, Dr. Kwok noted that a high-intensity statin is not advisable. He explained that the margin of benefit would be modest for increasing from moderate-intensity statin to high-intensity. In contrast, the impact of adverse effects associated with increasing statin dosage would be significant. Thus, Dr. Kwok would prescribe combined treatment, such as moderate-intensity atorvastatin with ezetimibe (atorvastatin/ezetimibe), when moderate-intensity statin monotherapy fail to achieve the target LDL-C level.

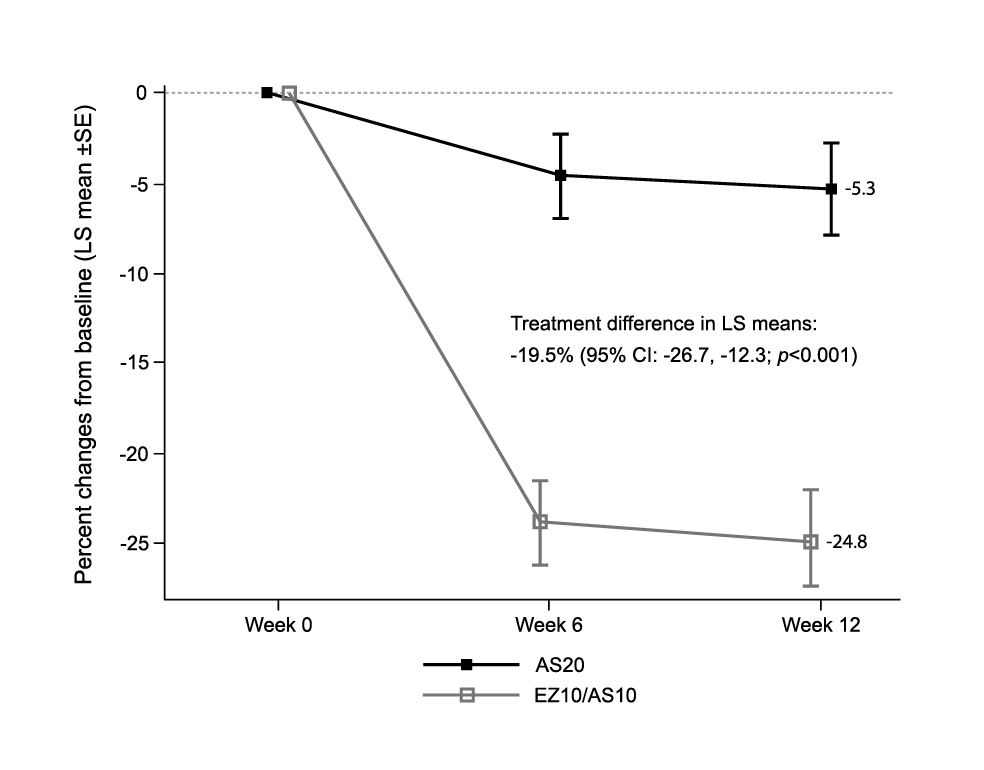

As a key regimen of combined therapy controlling LDL-C levels, the clinical performance of atorvastatin/ezetimibe has been supported in numerous clinical studies. For instance, a recent phase 3 randomised controlled trial (RCT) by Qian et al. (2022), which involved 454 Chinese patients with hypercholesterolemia uncontrolled with statin monotherapy, demonstrated that the percentage change from baseline in LDL-C was statistically greater with atorvastatin/ezetimibe 10/10mg treatment (n=88) compared with atorvastatin 20mg monotherapy (n=89) (treatment difference: −19.5%, p<0.001, Figure 1). The results also indicated that the safety profile was comparable between the atorvastatin/ezetimibe and atorvastatin monotherapy groups. Although increased number of urinary protein present (2.3% vs 1.1%), cerebral infarction (2.3% vs 1.1%), and hypertension (2.3% vs 0%) were reported in atorvastatin/ezetimibe group versus atorvastatin monotherapy group, no statistically significant difference in the occurrence of adverse events was observed9. Therefore, the findings suggested that atorvastatin/ezetimibe treatment offers a more effective treatment option for LDL-C management than escalated doses of atorvastatin, without compromising the safety profile.

Figure 1. Least squares (LS) mean percentage changes in LDL-C level after treatment with ezetimibe/atorvastatin (EZ/AS) or atorvastatin9, AS20: atorvastatin 20mg; EZ10/AS10: ezetimibe/atorvastatin 10/10mg

Translating clinical findings into real-life benefits, Dr. Kwok highlighted that statin/ezetimibe combined therapy effectively achieves LDL-C targets in his patients. He noted that many of his patients had received percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or had suffered from stroke and/or CVD. The patients are classified as high-risk or very high-risk categories and a more stringent LDL-C target of <1.4mmol/L or even <1.0mmol/L is thus recommended4. Accordingly, Dr. Kwok tends to prescribe statin/ezetimibe combined therapy early for these patients. “Along with lifestyle intervention, about 70% of the patients have achieved their treatment target with the combined treatments,” as per Dr. Kwok.

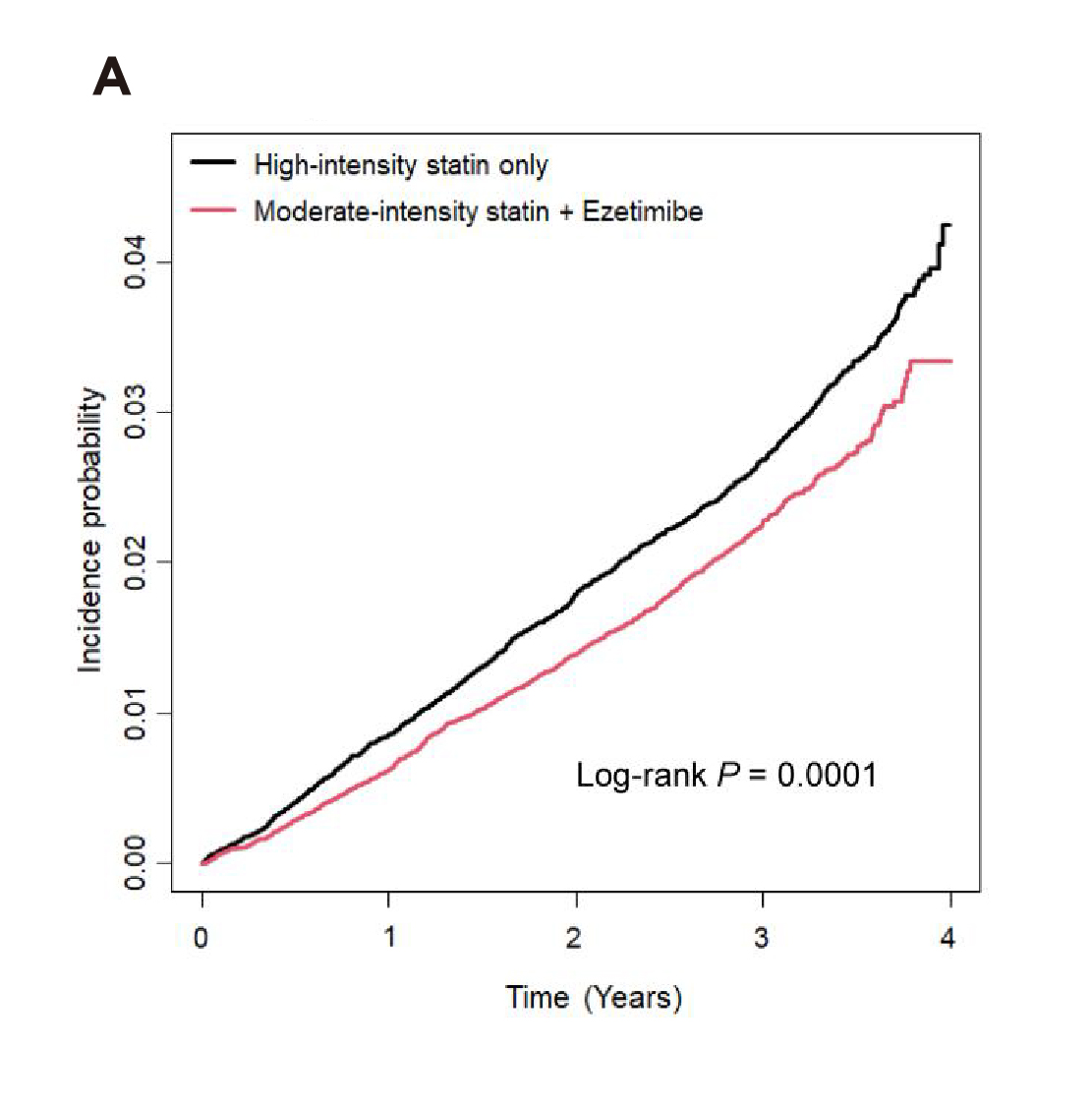

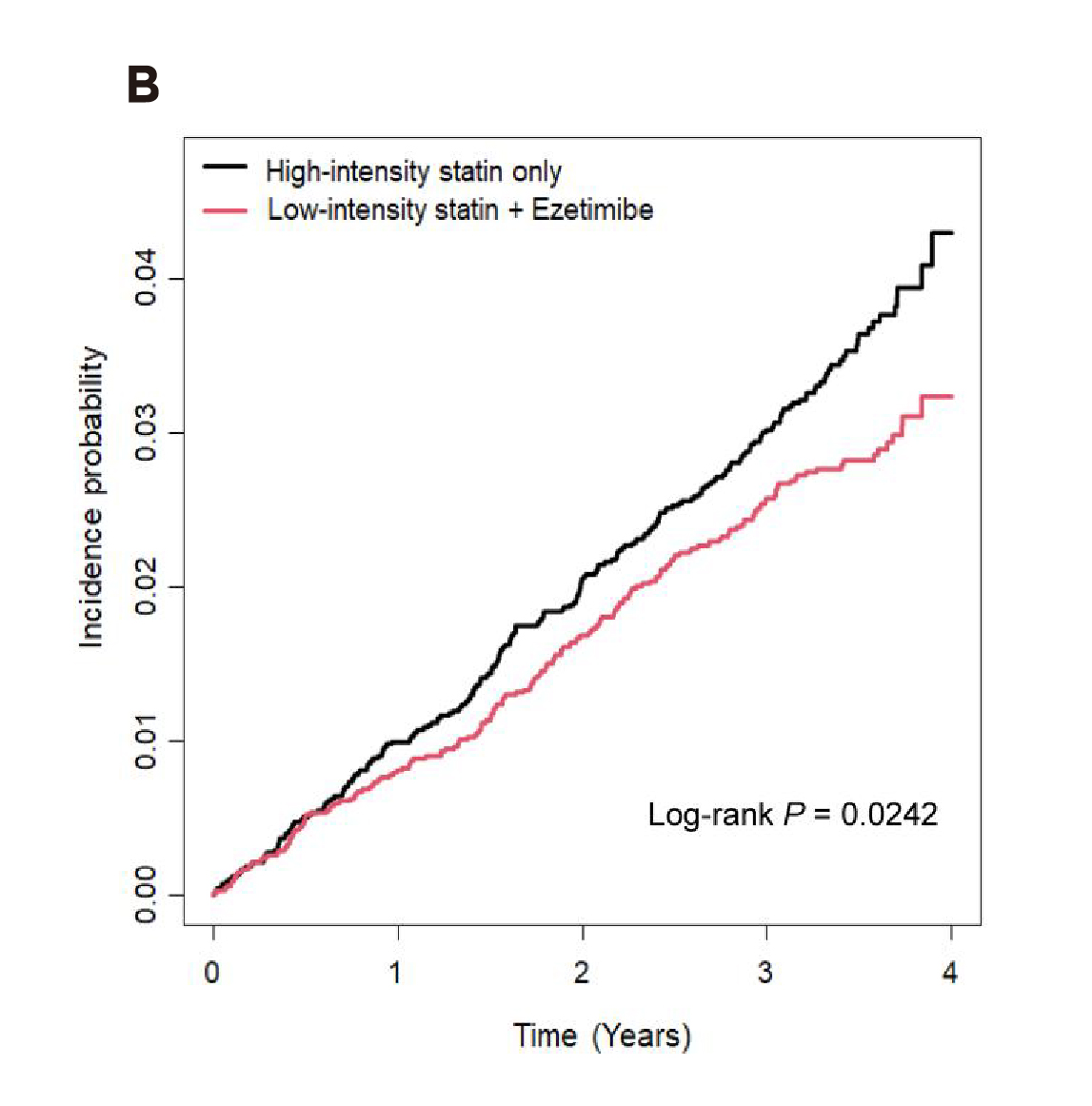

Undoubtedly, achieving the LDL-C target will likely result in improved health outcomes. A propensity-matched nationwide cohort study in Korea, which compared the preventive effect on CVD and all-cause death of low- or moderate-statin with ezetimibe combined therapy to that of high-intensity statin monotherapy among people without pre-existing CVD, suggested that the moderate-intensity statin with ezetimibe regimen significantly reduced the risk of composite outcome (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.84, p<0.001, Figure 2A) as well as individual myocardial infarction (MI, HR: 0.81, p=0.005) and stroke (HR: 0.78, p=0.005) compared to high-intensity statin monotherapy. Moreover, low-intensity statin with ezetimibe also significantly reduced the risk of the composite outcomes (HR: 0.80, p=0.024, Figure 2B) compared to high-intensity statin monotherapy2. Hence, the results indicated that statin/ezetimibe combined therapy was superior to high-intensity statin monotherapy in preventing composite outcomes among the participants.

While combined therapy would generate promising health outcomes, Dr. Kwok addressed the clinical significance of the single-tablet regimen of combined therapy in enhancing patient compliance. Previous studies reported that more than 50% of multimorbid patients have CVD and are often prescribed statins to reduce CV events and mortality in primary and secondary prevention10. Single-tablet regimens provide a strategic approach which supports the intensification of treatment without increasing the pill burden or treatment complexity. This would be particularly beneficial for older patients with comorbidities.

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier curves showing cumulative incidences of the composite outcomes between A) moderate-intensity statin with ezetimibe and B) low-intensity statin with ezetimibe combination therapy and high-intensity statin monotherapy group2

In response to the inquiry on selecting therapy, Dr. Kwok reminded that it is crucial to understand the patient’s medical history, with a particular focus on the previous treatments taken by the patient. Besides the patient's CV risk and LDL-C target, Dr. Kwok emphasised the importance of patient preference, which has to be considered in managing dyslipidaemia. “Some patients may be sensitive to the dosage of medications prescribed, and 40mg may be regarded as a very high dose for them”, he quoted. In these cases, lower-dose medications without compromising the efficacy may be considered as a measure to manage the patient’s expectations.

As indicated in existing clinical evidence, statin/ezetimibe combined therapy provides better control of LDL-C without increasing the risk of treatment-related adverse events as compared to higher-intensity statin monotherapy. The clinical observation by Dr. Kwok aligns with the clinical findings. Thus, he suggested not to push statin monotherapy to a very high intensity, such as atorvastatin 80mg or rosuvastatin 40mg. Instead, early prescription of statin/ezetimibe combined therapy can be considered to optimise the overall treatment outcomes.

To conclude, Dr. Kwok highlighted the importance of monitoring adverse events, such as liver impairment, and it is essential to be aware of adverse events developed after a prolonged period. “It is advisable for frontline colleagues to examine patients’ liver function and muscle enzymes regularly, as this facilitates early detection of adverse events,” Dr. Kwok opined. As a final remark, Dr. Kwok addressed that lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] is a novel risk factor for CVD and should be monitored in addition to LDL-C. “A higher risk category should be considered for patients with a high level of Lp(a), and more aggressive LDL-C reduction is warranted though it has not been updated in current guidelines,” he commented.

References

1. Du et al. J Clin Med 2023; 12: 363. 2. Jun et al. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2024; 31: 1205–13. 3. Li et al. Drugs 2025; 85. DOI:10.1007/S40265-024-02113-5. 4. Mach et al. Eur Heart J 2019; published online April. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455. 5. Chou et al. JAMA 2022; 328: 754–71. 6. Jose et al. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2016; 8: 23. 7. Selva-O’Callaghan et al. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2018; 14: 215. 8. Sénécal et al. Curr Med Res Opin 2009; 25: 47–55. 9. Qian et al. Clin Ther 2022; 44: 1282–96. 10. Adam et al. Front Cardiovasc Med 2023; 10: 1236547.