• Former President of Pediatric Infectious Disease Society of the Philippines

• Former Officer-in-Charge of the Assistant Director’s Office and the Chief, Clinical Research Division of the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM), Philippines

• Member of World Health Organization (WHO) Expert Panel on Rabies and the Asian Rabies Advisory Group of Experts

Rabies is a zoonotic disease caused by an RNA virus from the family Rhabdoviridae, genus Lyssavirus.1 Currently, rabies is prevalent in over 100 countries and regions worldwide.2 When rabies virus reaches the brain, the damage causes neurological symptoms.3 Once symptoms appear, rabies is almost 100% fatal.4 Rabies immunoglobulins (RIG) are presently used as post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for those exposed to the virus. However, due to certain concerns (such as cost, safety, and availability) for both human RIGs (HRIG) and equine RIGs (ERIG), a new treatment approach using a combination of two humanized monoclonal antibodies (mAb) has been proposed to offer better protection against various rabies virus (RABV) strains.5-8 To enhance the understanding of the current knowledge in this field, on December 13, 2024, the 11th Asian Congress of Pediatric Infectious Disease in Hong Kong invited Dr. Beatriz P. Quiambao, a renowned pediatric infectious disease specialist from the Philippines, to discuss issues on rabies PEP, and present SYN023, the world’s first humanized mAb cocktail for rabies.9*

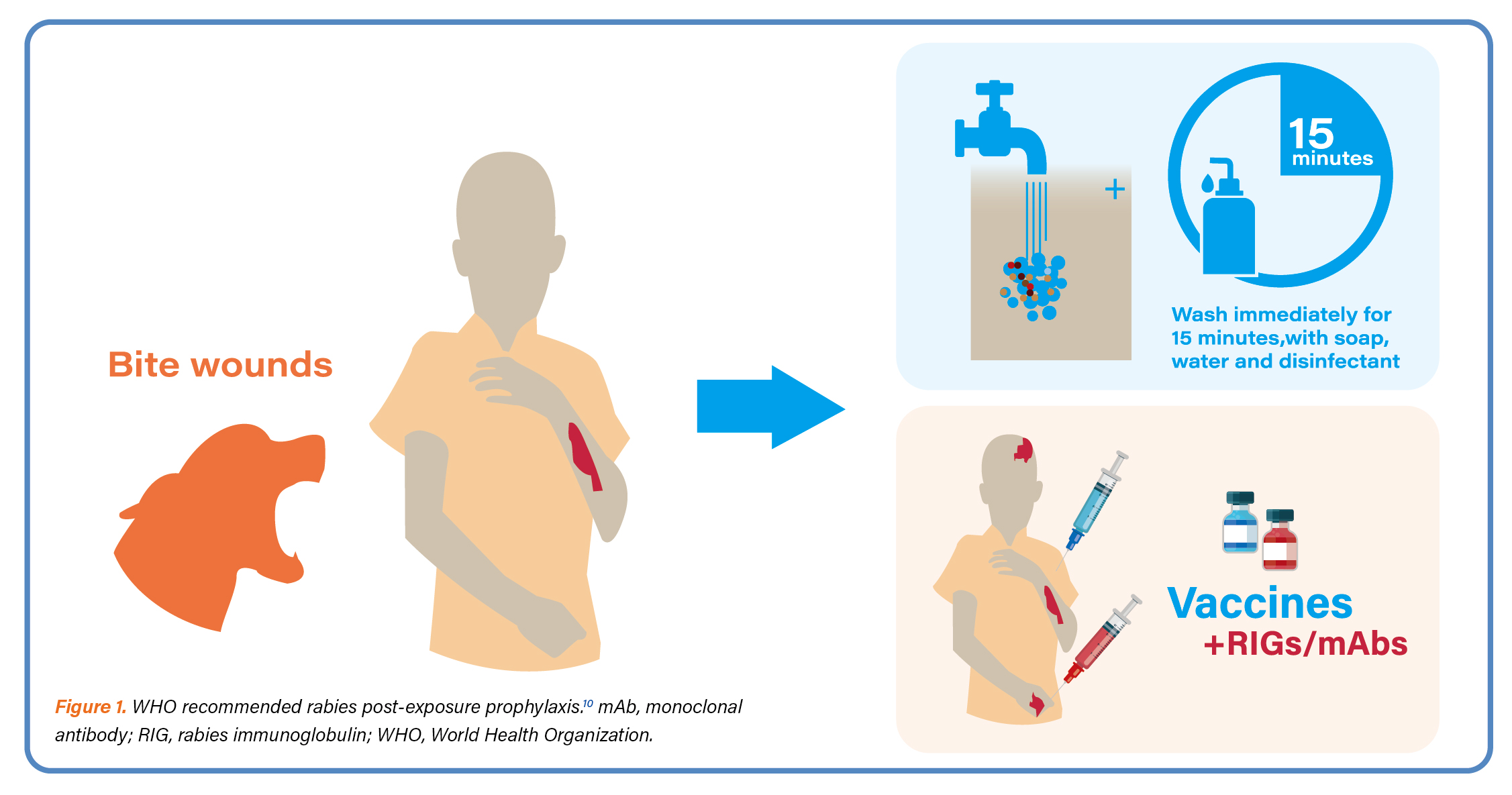

Dr. Quiambao started her presentation with the epidemiology of rabies. RABV belongs to a group of viruses referred to as lyssaviruses.1 More than 99% of human rabies cases are transmitted via dogs.1 Although canine rabies can be eliminated with the necessary tools in place for the control and elimination rabies remains a serious public health problem in more than 100 countries and territories, mainly in poor and rural areas of Asia and Africa.1,2,10,11 RABV can spend days to weeks in the body before it invades the nervous system.3 Once clinical symptoms appear, rabies is virtually 100% fatal.4 Rabies deaths are preventable with timely PEP which prevents the virus from reaching the central nervous system. PEP consists of extensive wound washing; a course of human rabies vaccine; and, if indicated, administration of RIGs (Figure 1).10

Dr. Quiambao opined that although RIGs are currently used as a PEP measure for individuals exposed to RABV, concerns are raised regarding their cost, safety, and availability. Both HRIG and ERIG pose a risk of transmitting bloodborne pathogens; and ERIG additionally carries a risk for severe allergic reactions. Despite HRIG being the preferred choice for PEP, it is expensive and often in short supply.5,6 These have led to WHO recommendations for using anti-RABV mAbs as an alternative treatment (Figure 1).7,10 Dr. Quiambao stressed that the WHO has put forward a recommendation that if mAbs are being considered for the prevention of rabies, then at a minimum, two mAbs targeting different antigenic sites of the glycoprotein should be included in the use of antibody cocktails.7,8 She then introduced to the audience SYN023, an antibody cocktail which is a mixture of two humanized mAbs, zamerovimab and mazorelvimab, that bind to non-overlapping epitopes on the RABV glycoprotein.12 The humanized mAbs are an ideal alternative to RIG since they are more affordable, safe, and can be produced on a large scale with standardized quality.13,14 SYN023 has been reported to neutralize a wide spectrum of RABV strains, covering 67 strains around the globe with 100% neutralization.8,15

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of SYN023, Dr. Quiambao led SYN023-004, a phase 2b randomized controlled trial, in which 448 patients in two risk substrata of WHO Category III exposure (Low Risk and Normal Risk Groups^) were randomly allocated to receive either 0.3 mg/kg SYN023 or 0.133 mL/kg HRIG, injected in and around the wound site(s), plus a course of rabies vaccination. Patients were followed for safety and absence of rabies for ≥1 year.12

Dr. Quiambao then shared effectiveness findings of SY023-004. Regarding the primary efficacy endpoints§, the geometric mean titer (GMT) of serum rabies virus neutralizing activity (RVNA) for the SYN023 group was superior to the HRIG group on Study Day 8 for both the low risk (SYN023 to HRIG ratio 29.64; 97.5 % confidence interval [CI]: 19.39, infinity) and normal risk groups (19.42; 97.5 % CI: 16.10, infinity) with P < 0.0001. On Day 99, the RVNA response rate, which is the proportion of subjects with RVNA serum concentration ≥ 0.5 IU/mL, showed non-inferiority of SYN023 in maintaining protective RVNA levels. No probable or confirmed rabies cases occurred in any of the study groups.12

Secondary endpoint¶ analyses showed that the GMT of RVNA was higher with SYN023 throughout the 2-week post-treatment period and was similar through Day 99. Remarkably, in the Normal Risk Group, 99.4% of SYN023 recipients (n = 154) had protective RVNA levels on Day 4 compared to only 4.5% of HRIG recipients (n = 156). On Day 8, 98.1 % SYN023 versus 12.2 % HRIG recipients were protected. The proportion of subjects with RVNA serum concentration ≥0.5 IU/mL was higher in the SYN023 group than HRIG through Day 15, and was similar through Day 99. A greater AUEC1-15 # was observed in SYN023 recipients.12

Regarding safety, Dr. Quiambao stated that SYN023 has an adverse event (AE) profile that is acceptable and manageable. Overall, the incidence rate of unsolicited treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE) was similar in both treatment groups. The majority of solicited TEAEs were mild or moderate; and there was no severe or very severe solicited TEAE. Additionally, there were no clinically significant changes in hematology, clinica chemistry, coagulation, vital signs, or physical examinations.12

In conclusion, rabies is a deadly infectious disease that targets mainly the central nervous system. SYN023 has been shown to act rapidly and provide a significantly higher RVNA level than HRIG shortly after exposure to rabies, a protection that is most needed especially in case of WHO Category III exposures. Although the RVNA concentrations decreased from Day 15 onwards, the observed levels of RVNA were not inferior to HRIG recipients. SYN023 also has a favorable safety profile. Thus, SYN023 represents itself as a potential effective and safe replacement for RIG against rabies virus.

* SYN023 has obtained approval by the National Medical Products Administration of mainland China in 2024; but has not been registered in Hong Kong.9

^ The Low Risk Group included bites to the foot, ankle, leg, or trunk; licks to broken skin; scratches with or to broken skin; unprotected bat exposure; or mucous membrane contamination by saliva or neural tissue. Bites to the head, neck, or genitalia were excluded from the initial and general enrollment. The Normal Risk Group included all exposures as per WHO Category 3 exposure, including bites to the head/neck, genitalia, arms and hands.12

§ The 4-part composite primary efficacy objective included the following elements: (1) to demonstrate that the Day 8 post-administration GMT of RVNA was superior in SYN023 recipients compared to HRIG recipients, (2) to demonstrate that the Day 99 GMT of RVNA was not inferior in SYN023 recipients compared to HRIG recipients, (3) to demonstrate that the Day 99 RVNA response rate (i.e. the percentage of patients with RVNA concentration ≥ 0.5 IU/mL) was not inferior in SYN023 recipients compared to HRIG recipients, and (4) to show absence of rabies infection in any SYN023 recipient through 365 days of post-administration follow-up.12

¶ Secondary objectives were to evaluate safety in each treatment arm, to demonstrate superiority of RVNA-based endpoints with SYN023 at additional time points (Day 4, Days 1–15), to describe RVNA response rates and GMT of RVNA ratios over the study period, to evaluate any impact of body mass index on RVNA in SYN023 recipients, and to assess incidence and effects of anti-drug antibodies.12

# Area under effective curve from Day 1 to 15.12

References

1. Ling MYJ, et al. BMJ Open. 2023;13(5):e066587. 2. Jiang X, et al. One Health. 2024;18:100743. 3. Cleveland Clinic. Rabies. 27 Augst 2022. Available from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/13848-rabies. [Accessed 23 December 2024]. 4. Willoughby RE Jr. Vaccine. 2009;27(51):7173–7. 5. Gogtay NJ, et al. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2018; 66: 387–95. 6. Jentes ES, et al. Journal of Travel Medicine.2014; 21: 62–6. 7. World Health Organization. WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies: Second report. 2013 8. Chao TY, et al. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(12): e0006133. 9. SYN023 Chinese Package Insert. 10. WHO. Rabies. 5 June 2024. Available from: https://www.who. int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rabies. [Accessed 20 December 2024]. 11. Hampson K, et al. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(4):e0003709 12. Quiambao BP, et al. Vaccine. 2024; 42(22): 126018. 13. Ding Y, et al. Antiviral Res. 2020; 184: 104956. 14. de Melo GD, et al. Current Opinion in Virology. 2022; 53: 101204. 15. Lyu XJ, et al. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2023;103(32):2475–9.