Professor of Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Medical University Vienna, Vienna, Austria

The availability of safe and effective oral direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has paved the path to eliminating hepatitis C (HCV) infection. Accordingly, the World Health Organisation (WHO) addressed a global target in 2016 for the elimination of HCV as a public health threat by 2030. However, only an estimated 21% of the global population with chronic HCV had been diagnosed, and only 62% of them were treated by the end of 20191. The identification of undiagnosed cases of HCV and subsequent treatment is additionally hindered by the fact that HCV is prevalent in socioeconomically deprived and marginalised groups, such as people who inject drugs (PWID)2. In the 37th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Hong Kong Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (HKASLD), Prof. Thomas Reiberger discussed the barriers towards HCV elimination in marginalised communities and outlined effective strategies to overcome barriers to an effective cascade of care towards HCV cure.

According to the Thematic Report on Viral Hepatitis 2020-2022, the overall prevalence of viraemic HCV infection in Hong Kong was 0.26% among local persons aged 15 to 84, and the prevalence was similar between females (0.43%) and males (0.20%). Of note, among persons who tested positive for HCV RNA (HCV-RNA+), 59.2% were infected by HCV genotype 1b representing the most common HCV genotype, whereas 19.9% were infected by HCV genotype 2, and 20.9% were infected by HCV genotype 63.

Prof. Reiberger commented that the local HCV prevalence was different from that of Europe. For instance, Thomadakis et al. (2024) recently reported that the chronic HCV prevalence in 29 of 30 European Union (EU)/European Economic Area (EEA) countries in 2019 was 0.50%, with the highest prevalence observed in eastern EU/EEA (0.88%). Essentially, the report highlighted that at least 35.76% of the overall chronic HCV prevalence in EU/EEA countries was associated with injecting drugs4.

As per Prof. Reiberger, PWID, people living with HIV (PLHV), and people who are incarcerated5 represent the marginalised populations at the greatest risk of HCV infection. He noted that the high HCV prevalence among PWID is mostly attributed to needle sharing. The shared transmission routes of HIV and HCV increase the risk for these co-infections. Besides, over-representation of PWID, lack of systematic screening programs, and limited access to care and treatment were found to be main reasons for the high HCV prevalence in prisons6.

Focusing on the scenario of PWID, an HCV seroprevalence study conducted in local methadone clinics by Lee et al. (2006) reported an 85% prevalence rate of anti-HCV seropositivity in this community7. Additionally, another study by Wong et al. (2013) involving PWID recruited at their gathering places indicated an anti-HCV prevalence of 81.7%8. Apart from the current PWID, a local study involving 365 ex-PWID revealed that 73.4% of the participants were HCV-positive9. Hence, the findings highlighted the urgent need for effective strategies to reduce HCV prevalence in marginalised communities.

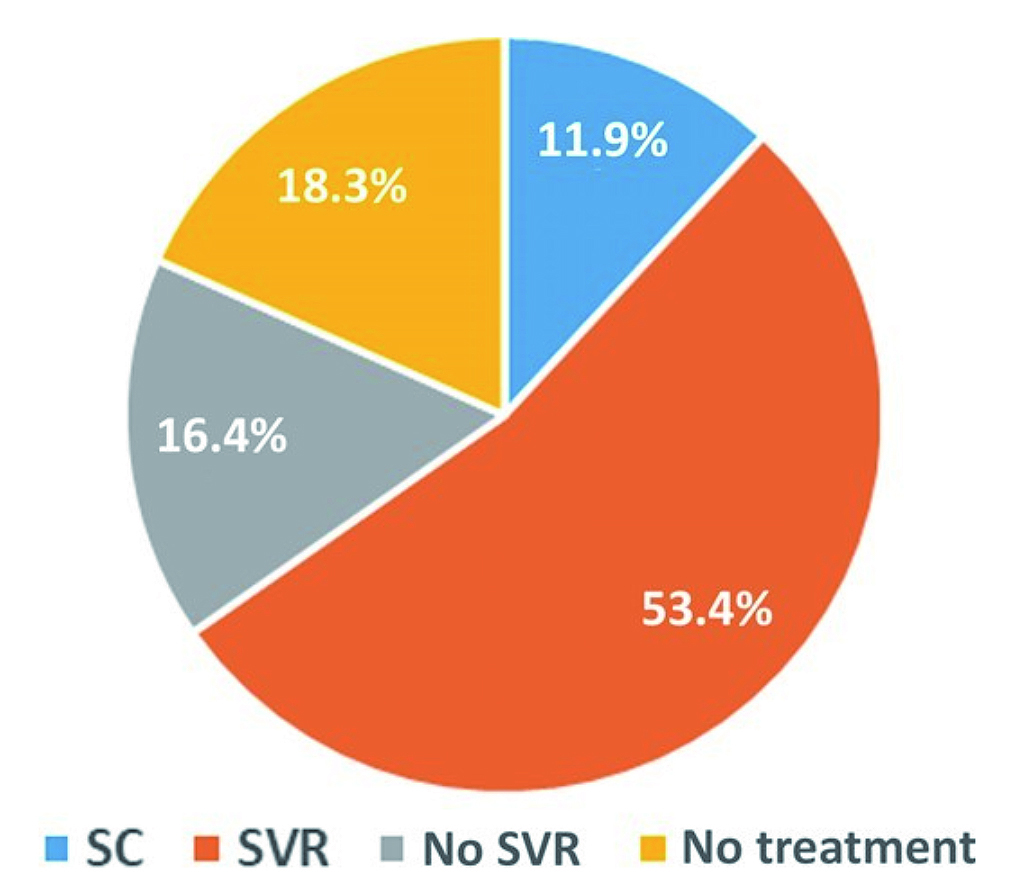

The incidence of hepatitis C can be dramatically reduced by using DAAs for persons recently infected with HCV. Prof. Reiberger noted that the spontaneous clearance (SC) rate of recently acquired HCV is low, and most cases become chronic. As demonstrated in the PROBE-C study by Monin et al. (2023), which included 464 HIV-positive persons recently infected with HCV, only 11.9% achieved SC, while the remaining cases had progressed to chronic infection with persistent viremia of HCV. Importantly, 18.3% and 16.4% of cases, respectively, had not received antiviral treatment and did not achieve sustained virologic response (SVR) despite treatment (Figure 1)10. Prof. Reiberger stressed that a delay in clearing HCV, i.e. resulting on ongoing viremia would pose an ongoing transmission risk for HCV transmission.

Figure 1: Virologic outcomes in PROBE-C study10

Prof. Reiberger outlined that providing HCV care to the marginalised cohorts is practically difficult due to stigmatisation, unstable housing, and mistrust of the healthcare system5. Remarkably, many individuals are unaware of their HCV infection status and have limited access to healthcare services. Moreover, poverty and high out-of-pocket costs for treatment also hinder treatment for the marginalised HCV communities. Besides patient-related factors, Prof. Reiberger noted that inadequate national policies, lack of integrated care systems, and restrictive treatment guidelines are additional barriers to HCV treatment.

Prof. Reiberger emphasised that DAAs are highly effective and can cure hepatitis C in literally all patients. "If a patient remains compliant with intake of the antiviral medication, they will be cured from HCV", he said. The recent SVR10K study by Aleman et al. (2024) provided real-world evidence on the efficacy of 12-week DAA treatment with sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (SOF/VEL) without ribavirin (RBV) across 10 study sites globally, accounting for >6,000 HCV patients. The results indicated that among the effectiveness population (n=6,095), >98% of the patients showed SVR outcomes, regardless of sex (99.0% in females vs 98.7% in males) and age (under 50 years: 99% vs above 50 years: 98%)11. The results thus confirmed the pan-geographic efficacy across age and gender of SOF/VEL in real-world settings.

While SOF/VEL effectively suppresses HCV viral load, the treatment outcomes may be affected by patient adherence. Accordingly, the SIMPLIFY study by Cunningham et al. (2018) investigated treatment adherence to 12 weeks of once-daily SOF/VEL treatment among HCV-infected people with recent injecting drug use. Among the participants who completed treatment (n=100), 32% were considered non-adherent (<90% adherence). Interestingly, the results reflected that the SVR was still similar among adherent and non-adherent populations (94% vs 94%, p=0.944)12.

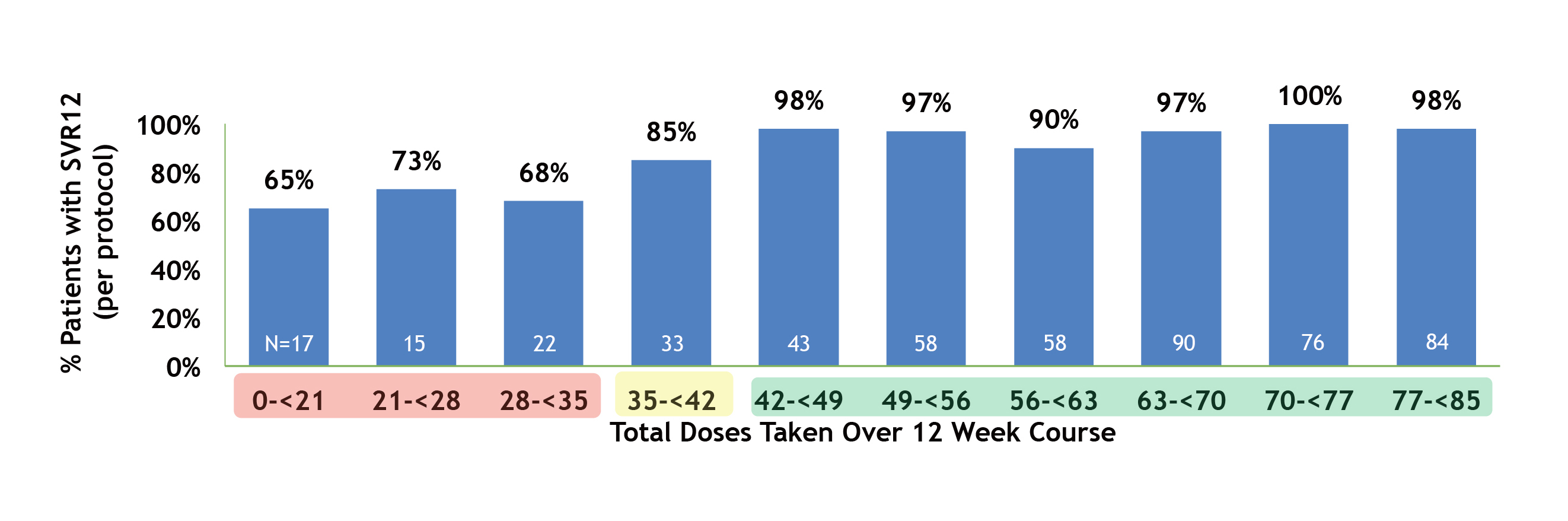

Besides, a prospective, multi-centre pragmatic trial of community-based SOF/VEL therapy involving 755 HCV-infected people who use drugs (PWUD) by Litwin et al. (2022) indicated that 85% of participants achieved SVR at week 12 (SVR12) with at least 35 doses over the 12-week treatment course, whereas 65% of participants achieved SVR12 with <21 doses of SOF/VEL (Figure 2)13. Therefore, the result suggested that a high proportion of participants receiving SOF/VEL achieved SVR though the adherence was suboptimal.

Figure 2: SVR12 rate by total SOF/VEL doses taken over 12 Weeks13

In addition to using effective therapy, Prof. Reiberger highlighted the implication of a simplified HCV management approach, the Minimal Monitoring (MinMon) Strategy. “It (MinMon strategy) may be useful to cut the unnecessary steps, while genotyping is easily be crossed out since we have SOF/VEL, which requires no pre-treatment genotyping and its dosing is simple,” he commented. The MinMon strategy is particularly useful in settings with limited resources.

Prof. Reiberger outlined that the MinMon strategy was characterised by 4 components: (i) no pre-treatment genotyping, (ii) dispensing full treatment, i.e. all 84 SOF/VEL tablets at initiation, (iii) no scheduled face-to-face visits or laboratory monitoring during treatment and (iv) remote contacts at week 4 for adherence and week 12 for SVR scheduling. The outcome of the MinMon strategy in managing HCV was confirmed in the phase-4 MINMON trial by Solomon et al. (2022) that 89% of the 397 patients reported taking 100% of the SOF/VEL treatment during the 12-week course, and 95% of the patients who initiated treatment achieved SVR14. Hence, the MinMon strategy with SOF/VEL regimen effectively reduces the burden on the healthcare system without compromising patient compliance and efficacy to cure HCV.

Retaining persons in marginalised communities to HCV care is challenging and thus, patient adherence to antiviral treatment may be suboptimal. Undoubtedly, health education and social support by government and non-government organisations (NGOs) are crucial to improving awareness of HCV and its potential consequences and promoting diagnosis and treatment rate. According to Prof. Reiberger, effective therapy and a simplified HCV management approach are essential to optimise treatment outcomes. In this regard, the MinMon strategy with SOF/VEL treatment has been demonstrated to be an effective strategy for eliminating HCV.

References

1. Klein. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 7: 277. 2. Cook et al. Public Health 2024; 232: 153–60. 3. Centre for Health Protection - Population Health Survey 2020. 4. Thomadakis et al. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe 2024; 36: 100792. 5. Heath et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024; 9: 286–8. 6. Kronfli et al. Canadian Liver Journal 2019; 2: 171. 7. Lee et al. J Clin Virol 2008; 41: 297–300. 8. Wong et al. Int J Infect Dis 2013; 17. DOI:10.1016/J.IJID.2012.10.004. 9. Wong et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 34: 1641–7. 10. Monin et al. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76: E607–12. 11. Aleman et al. EASL 2024: THU374. 12. Cunningham et al. International Journal of Drug Policy 2018; 62: 14–23. 13. Litwin et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 7: 1112–27. 14. Solomon et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 7: 307–17.