BDS, MDS, PhD, FCDSHK, FHKAM

• Tam Wah-Ching Professor in Dental Science

• Professor, Chair of Dental Public Health

• Clinical Professor, The Faculty of Dentistry, the University of Hong Kong

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a chronic gastrointestinal (GI) disorder characterised by the regurgitation of gastric contents into the esophagus1. It is one of the most commonly diagnosed digestive disorder1 with a global prevalence of 783.95 million in 20192. Remarkably, around 5-10% of local population in Hong Kong reported experiencing acid reflux weekly3. Although, the reported incidence of GERD is much lower in the Chinese population compared to Caucasians4, the prevalence of GERD has steadily been increasing in Asian over the last few years and rates are beginning to approach those reported in Western countries5. Notably, the risk factors for GERD include obesity, poor dietary habits, consumption of excessive alcohol, pregnancy, drug-induced, cigarette smoking, and stress1,3. Patient with GERD often complain of experiencing post-prandial burning sensation in the retrosternal area and acid regurgitation6. As the condition progresses, patient may experience a number of complications including erosive esophagitis, esophageal ulcers, strictures, and Barett’s metaplasia3. Not surprisingly, GERD is also associated with a significant economic impact as it affects individual’s quality of life (QoL)7. Currently, there are no gold standard for diagnosing GERD, thus diagnosis is often based on combination of presenting symptoms, endoscopic evaluation of the esophageal mucosa, reflux monitoring, and response to therapeutic intervention (8-week trial of empiric proton pump inhibitor [PPI] once daily before meal)8. GERD is a risk factor of dental erosion (DE)9. Stomach acid in GERD rises through the esophagus into the oral cavity, causing enamel erosion also named as DE, which leads to dentine hypersensitivity (DH)10. According to Picos et al., the prevalence of DE in GERD patients was higher as compared to control group (48.8% and 20.5%)9. According to the meta-analysis of Jordao et al., a 4.1-fold increased probability of DE in individuals with objectively measured GERD (pooled OR 4.1, 95% CI: 1.7–10.1) and a 2.7-fold in individuals with subjectively measured GERD/S, when compared to controls (pooled OR 2.7, 95% CI: 1.1–6.4) were recorded9.

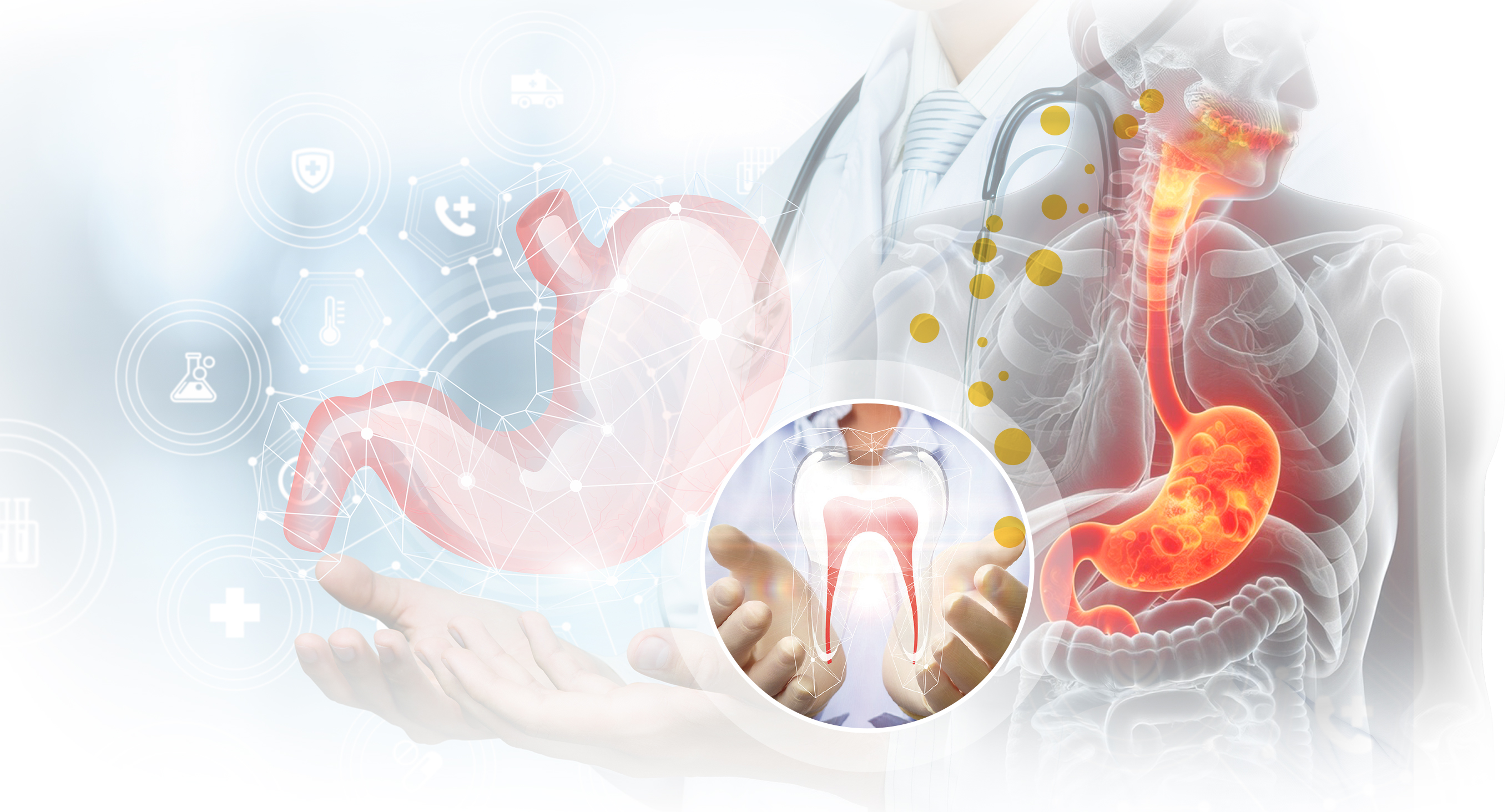

DE is defined as tooth surface loss caused by chemical or electrochemical processes of non-bacterial origin11. DH is defined as a short, sharp pain that arises from exposed dentin in response to non-noxious stimuli, typically thermal, evaporative, tactile, osmotic or chemical, and that cannot be ascribed to any other form of dental defect or disease12. One commonly accepted theory is hydrodynamic theory, which suggests that changes in the fluid flow in dentinal tubules can trigger pain receptors present on nerve endings located at the pulpal aspect to fire nerve impulses, thereby eliciting pain12. There are various clinical conditions thought to play a role in the development of DH including DE, enamel attrition, and abrasion. Aggressive tooth brushing can also lead to the exposure of dentin, which ultimately leads to the development of DH11. Globally, 1 in 3 people may suffer from DH, peaking at 30 to 40 years old13. Locally, according to the oral health survey 2021 conducted by the Department of Health of Hong Kong SAR government, around 55% of individuals aged 35-44 had experienced dental sensitivity within a year and most of them either did not take any action or managed the oral symptoms by themselves rather than attending dental consultation (Figure 1)14. Two thirds (67.7%) of Hong Kong patients with periodontal condition had DH problem15. The vast majority (92%) of Hong Kong adults aged 25-45 years reported at least one symptom related to DE11. Understandably, people affected by DH often report its substantial impact on their daily lives when eating, drinking or even brushing16. More severe DH can last for more than 6 months and become consistently annoying, inducing psychological and emotional distractions9.

Figure 1: Proportion of adults according to the oral symptoms experienced (dental sensitivity marked in red box) in the 12 months before the survey and the action taken in 202114.

DE occurs by dissolving mineralized tooth tissues when exposed to non-bacterial acid. One of the factors that predispose individuals to DE is GERD due to chronic regurgitation of gastric contents to the oropharynx. Thus, individuals with GERD may have DE lesions as extraesophageal manifestations17. Of note, the upper incisors’ palatal surfaces are initially attacked by refluxed acid, as the situation persists, the occlusal surfaces of posterior teeth in both arches erode. Similarly, the lower teeth are initially shielded by the tongue, but as the disease persists, the occlusal and buccal surfaces of these teeth eventually deteriorate18. Relentless exposure to pH below 5 will cause hydroxyapatite crystal in the dental enamel to dissolve and the tooth may have a yellowish tint due to tooth thinning, in addition to becoming overly sensitive to external stimuli18. A cross-sectional study by Ali et al. (2024) reported that individuals with DE who consumed more packaged food, pickles, soft drinks and sweets had a higher risk of DE19.

Since DE often causes dentin exposure which invariable leads to the development of DH, the repercussion of the disease can be detrimental to patient’s well-being. It is important to note that DH is always provoked subsequent to the delivery of an external stimulus, and rarely if ever present as pain that is either continuous or spontaneous9. The sequela of DH becomes apparent as the condition merits a serious burden on the individual’s psychosocial and financial life20. Furthermore, DH can also alter the way patients act, restricting their eating habits, cause them to make adaptations to daily life and affect their social interactions as well as having emotional impact and affecting their personal identity21. In order to capture the nuances of DH’s impact on QoL, the Dentin Hypersensitivity Experience Questionnaire (DHEQ) was developed to evaluate responsiveness to change in oral health-related QoL measures in DH patients22,23. Interestingly, research utilizing the DHEQ has found that among patients with DH, the adaptive behaviours fall into 4 categories: avoid, adapt, compromise and tolerate24. However, patients should not only be dependent on adaptive behavioural change. Instead, dental professional should openly discuss issues related to DH and offer treatment option during dental consultations16.

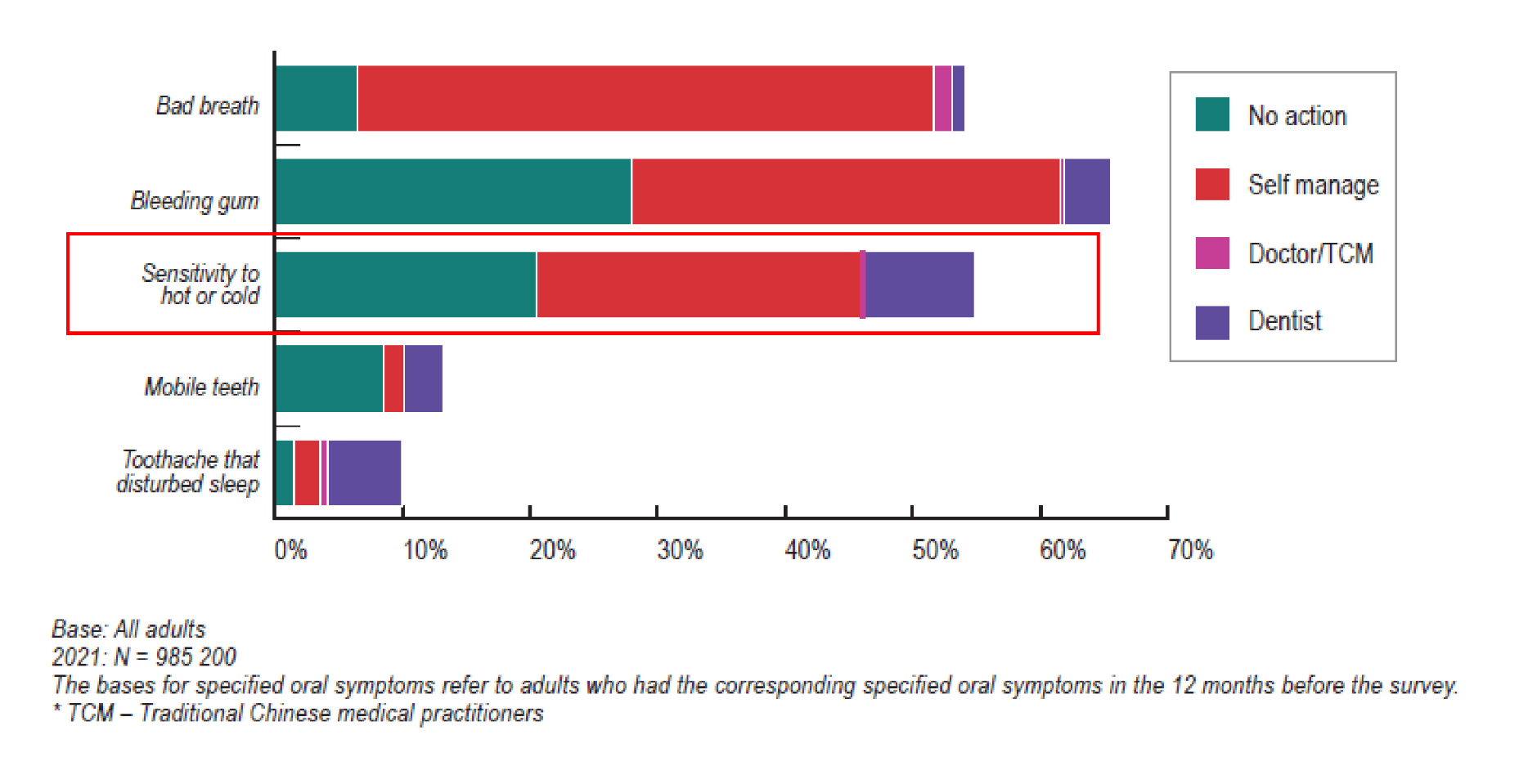

Treatment of DH is based on a thorough medical and dental history together with a clinical examination leading to a definitive diagnosis based on these findings. Detailed DH diagnosis and management guideline can be found in Figure 212. Effective treatment and controlling DH remain an important issue for dentists25. Strategies for management of DH include oral hygiene education, behavioural control and elimination of predisposing factors for DH, in addition to non-invasive treatment for pain relief9. In this context, toothpastes have been used in the treatment of DH since it is an easy, non-invasive, and most comprehensive way to treat hypersensitivity26. The best results are achieved if desensitizing toothpaste is applied via twice-daily brushing12. Notably, the primary aim here is to reduce the fluid flow in dentin tubules or block the nerve response in the pulp using various ingredients in desensitizing toothpastes, including potassium nitrate, stannous fluoride, arginine, and calcium sodium phosphosilicate (NovaMin). The mechanisms applied in tooth desensitizing are mainly by two pathways: nerve desensitization and tubule occlusion12,25. Each ingredient used in these desensitizing toothpastes is discussed as follows:

Figure 2: Algorithm for diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity12

KNO3 has been incorporated into desensitizing toothpastes to reduce nerve excitation. This then increases the concentration of potassium ions, which is believed to decrease the excitability of the nerve against the action of sodium ions27. The efficacy of toothpaste containing KNO3 was evaluated in a study by Pradeep et al. (2012) that included 149 subjects (72 males and 77 females; aged 20 to 60 years) randomly divided into 4 groups: Group 1- toothpaste containing 5% KNO3; Group 2- toothpaste containing 5% calcium sodium phosphosilicate with fused silica; Group 3- toothpaste containing 3.85% amine fluoride; and Group 4- a placebo toothpaste. After sensitivity scores for controlled air stimulus and cold water at baseline were recorded, subjects were given toothpaste and sensitivity scores were measured again at 2 and 6 weeks. Group 1 toothpaste with 5% KNO3 showed significant reduction in all sensitivity scores at weeks 2 and 6. The percentage decrease from baseline for the 5% KNO3 dentifrice at week 6 was 57.1% and 54.4% in air and water stimulus, respectively. The comparison between test group with 5% KNO3 and negative control group was also significant28.

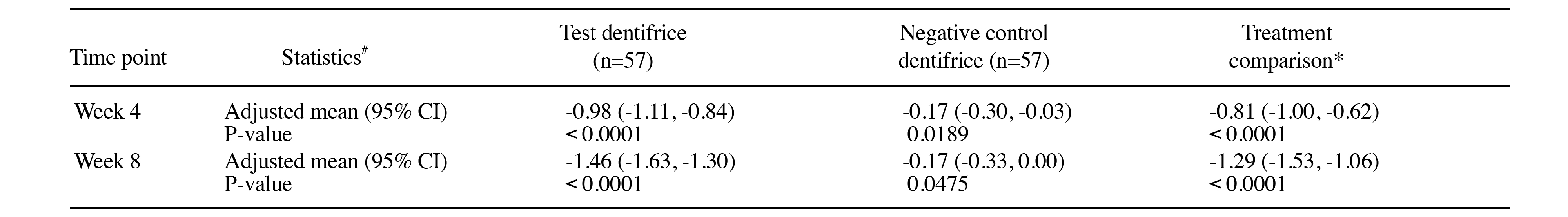

SnF2 is a scientifically recognized ingredient to strengthen enamel, relieve DH and protect gums29–31. SnF2-based toothpaste works by forming an insoluble metal compound that precipitates into the dentin tubules to reduce dentin permeability to the stimuli32. In a randomized, examiner-blind, parallel, two treatment group, 8-week clinical study that compared the efficacy of an anhydrous dentifrice containing 0.454% weight to weight (w/w) stannous fluoride and a negative control dentifrice containing 1,000 parts per million (ppm) fluoride, as 0.76% w/w sodium monofluorophosphate, at reducing DH over 8 weeks with twice-daily brushing was evaluated. The study included 119 healthy subjects with at least two sensitive teeth, and 113 participants completed the study. Remarkably, at 4 and 8 weeks, between treatment analyses found that 0.454% w/w stannous fluoride dentifrice was significantly better than the negative control dentifrice in relieving DH for all measures (Schiff: p<0.0001 at 4 and 8 weeks; Visual Analogue Score [VAS] score: p=0.0003 at 4 weeks, p<0.0001 at 8 weeks; tactile threshold: p=0.0138 at 4 weeks, p<0.0001 at 8 weeks). At week 8, there was statistically significant decrease in adjusted mean Schiff sensitivity score from baseline for both the test (p<0.0001) and the negative control (p=0.0475 at week 8) (Figure 3)33. Noticeably, the percentage decrease from the baseline for the test dentifrice was 65.5% at week 8, with respective figure for the negative control of 7.4%33.

Figure 3: Summary of 4- and 8-week change from baseline Schiff sensitivity scores for the ITT population (n=114). #From ANCOVA model: Treatment as fixed factor, baseline Schiff sensitivity score as a covariate. *Difference is test dentifrice minus negative control dentifrice such that a negative difference favors test dentrifice33. CI, confidence interval; ITT, intention-to-treat.

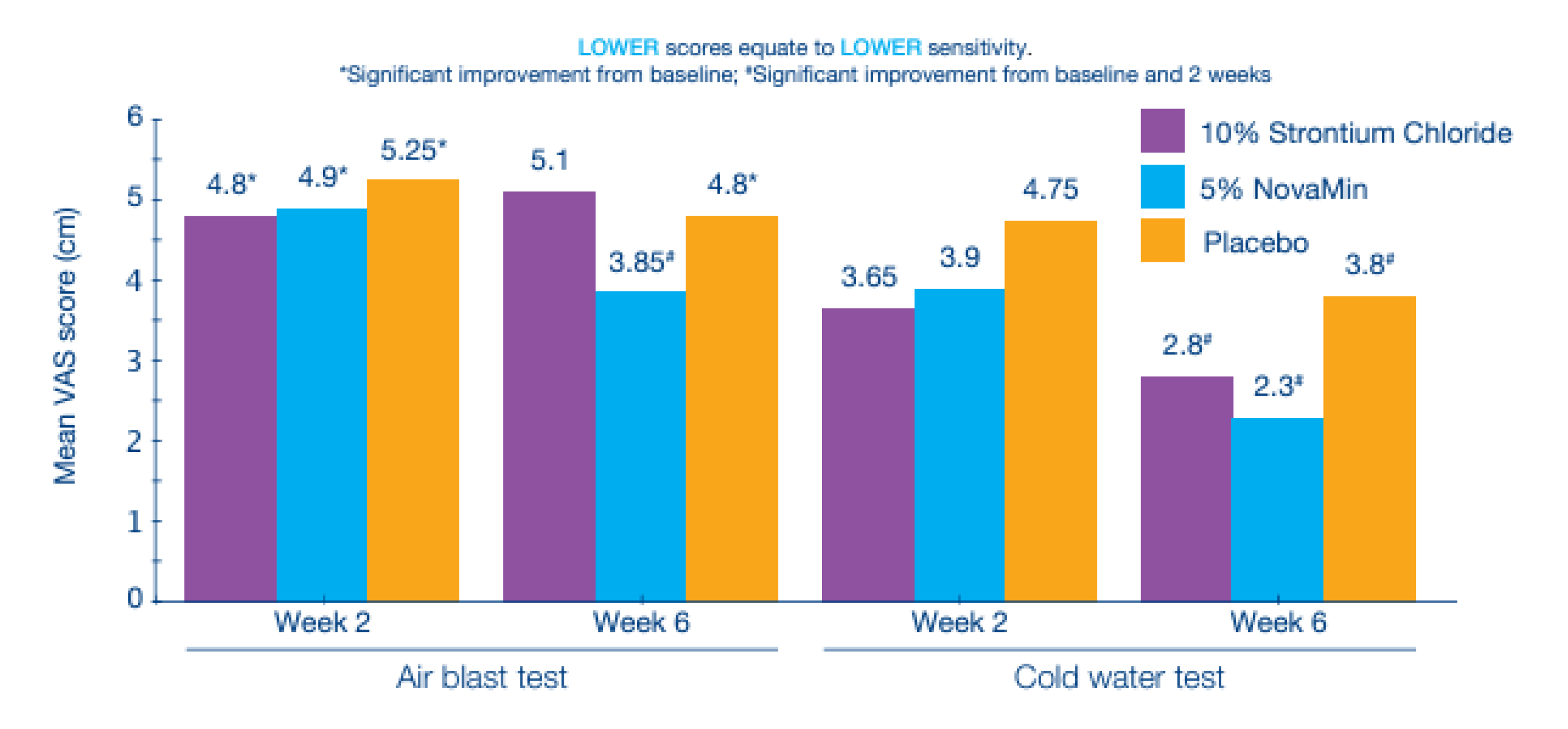

NovaMin, also known as calcium sodium phosphosilicate has shown to bind to the collagen fibers in the exposed dentin, acting as a reservoir of minerals such as phosphate and calcium, forming a robust and repairing layer similar to hydroxyapatite on the exposed dentin tubules. Furthermore, the instantaneous contact of the components in an aqueous medium with saliva promotes the release of calcium and phosphate, forming an insoluble remineralizing hydroxyapatite carbonate on the enamel surface26. NovaMin is a highly water-reactive phosphosilicate consisting of fine powder particles that can physically obstruct dentin tubules and also demonstrate broad clinical efficiency in the enamel remineralisation process. These findings were substantiated in a double-blinded, parallel group randomized clinical study that compared the clinical efficacy of two commercially available toothpastes containing either 5% w/w NovaMin or 10% w/w strontium chloride and a matched placebo control toothpaste on DH. Remarkably, after the evaluation period, it was observed that after stimulation with a blast of air, 58% of subjects treated with NovaMin reported improvement in sensitivity, compared to only 26% of the group treated with 10% strontium chloride toothpaste and 20% with placebo (Figure 4)34. The results obtained demonstrated that the toothpaste containing NovaMin was more effective in reducing sensitivity compared to a commercial dentifrice and a placebo control. NovaMin can also enable the fill up of irregularities on enamel surface and thereby prevent erosion from acidic exposure. In addition, the eroded surface defects can be remineralised by providing calcium and phosphate and thereby reduce the mineral loss35.

Figure 4: After 6 weeks of twice daily brushing use, NovaMin resulted in greater reduction in sensitivity (air and cold-water tests) than the placebo and 10% strontium chloride toothpaste34.

Arginine is an essential amino acid with an alkaline pH, and its dentin-desensitizing effect in combination with calcium carbonate (as a rich source of calcium ions) has been proven in previous studies. Since both arginine and calcium ions are positively charged at physiological pH (alkaline by bicarbonate buffer), they are able to bind to negatively charged dentin surface and create a calcium-rich layer36. The effect of arginine-containing desensitizing toothpaste on DH was evaluated in a meta-analysis by Yang et al. (2016). In the analysis, 18 RCTs with 1,423 patients were included and the results demonstrated that at days 0, and 3; weeks 2, 4, and 8; and more than 12 weeks, arginine-containing toothpaste led to significantly improved results on tactile sensitivity test (standardized mean difference [SMD] =1.95, 95% confidence interval [CI] [1.14, 2.76]) and the air-blast test (SMD =−1.60, 95% CI [−2.14, −1.05]) at 4 weeks and the tactile sensitivity test (SMD =2.01, 95% CI [1.41, 2.61]) and the air-blast test (SMD =−1.41, 95% CI [−1.83, −0.98]) at 8 weeks compared to toothpastes containing other desensitizing components, thus indicating a superior therapeutic effect of arginine-containing desensitizing toothpaste. However, no significant differences between arginine-containing toothpaste and toothpastes containing other desensitizing components were observed in the air-blast test at days 0 and 3 and week 2 and in the tactile sensitivity and air-blast tests at more than 12 weeks37.

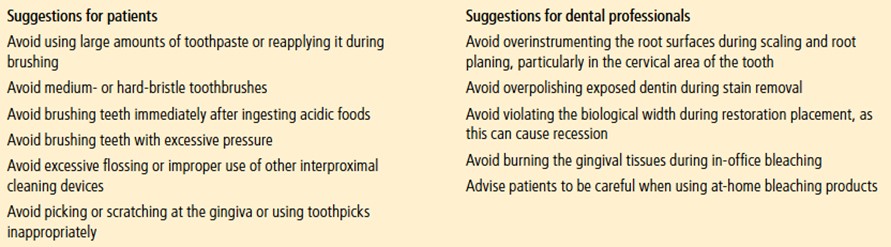

Systematic reviews and meta-analysis have proven efficacy and QoL improvement of desensitizing agents such as KNO3, stannous fluoride, arginine and NovaMin29,35,38–41. Although patients can simply use desensitizing toothpastes in their daily oral hygiene practices, clinical advice may help provide better maintenance for DH prevention and management. For instance, using soft-bristle toothbrush, applying 1,350-1,500 ppm fluoride toothpaste daily for adults, and expectorating excess toothpaste instead of rinsing with water straight after brushing to let the active ingredients to continue functioning. Furthermore, by simply avoiding toothbrushing immediately after meal, and avoid having in-office bleaching or using at-home bleaching tooth-whitening products such as carbamide peroxide and hydrogen peroxide, individuals can reduce their risk of DH12,42. Fluoride plays a pivotal role in enamel remineralization to combat against DE and tooth decay. Thus, it is important that the toothpaste has fluoride42. For patients who are keen to prevent both DH and tooth stain problems, they should use a single fluoride toothpaste that provides all the benefits including dental densensitization, non-bleaching whitening and enamel safe. In summary, toothbrushing with desensitizing toothpaste is recommended for preventing and treating both the DE and DH, which should be considered as a management tool in GERD patients.

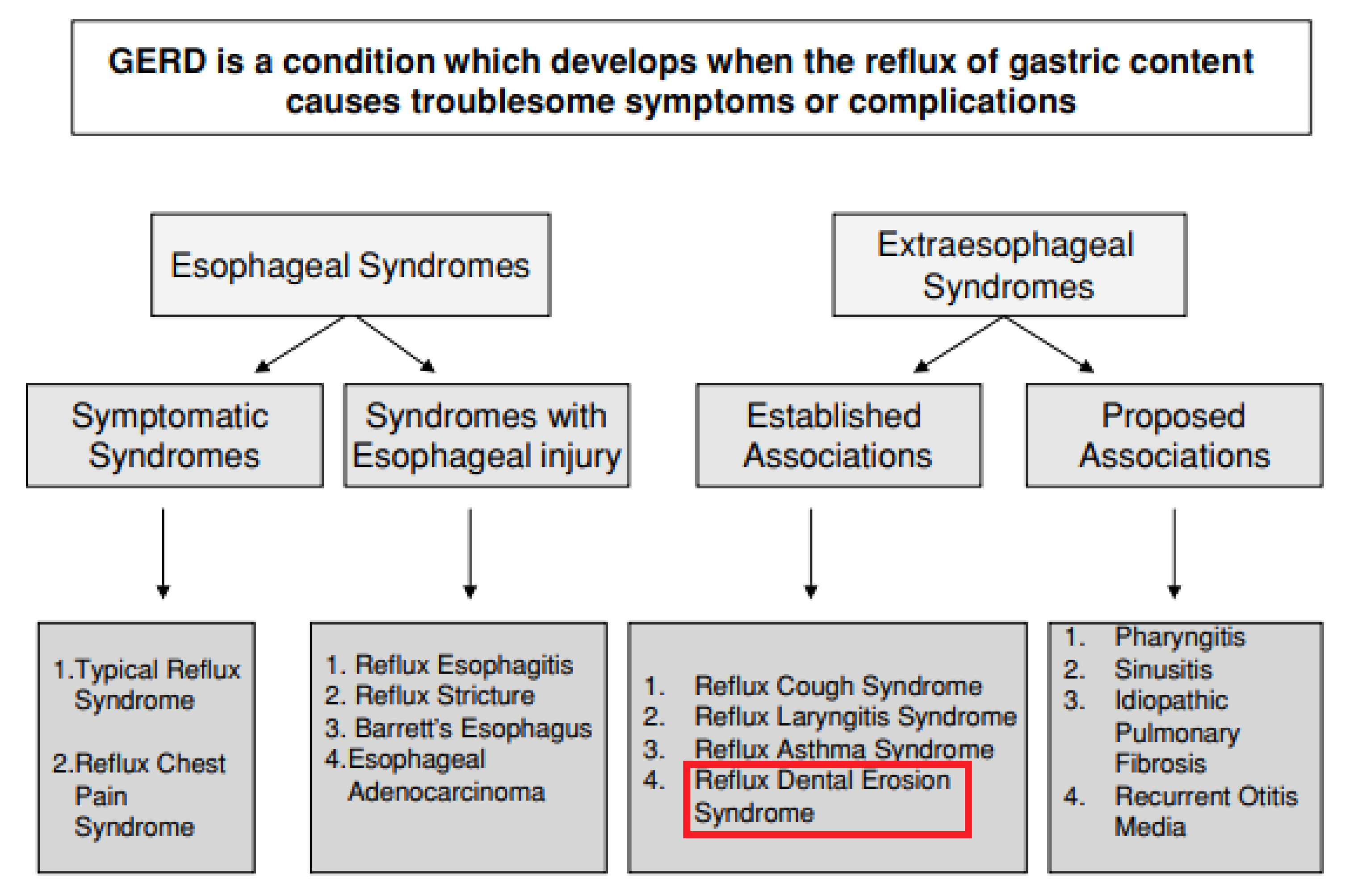

DH is a widespread condition and over 70% of sufferers consider the sensations to take pleasure out of eating and drinking43. Moreover, DH carries a significantly negative effect on a person’s oral health-related QoL since it has detrimental effect on their financial, personal and social lives. Erosion of enamel driven by gastric reflux disease or ingestion of acidic substance has been identified as trigger or exacerbators of DH44. It is now believed that DE and GERD are related18 and DE is considered an extraesophageal symptom as per the Montreal classification of GERD (Figure 5)45. Furthermore, GERD management nowadays has increasingly taken a multidisciplinary approach involving both the gastroenterologist and dentists45. Since acid reflux from the gastric environment often causes the salivary pH to fall and this represents an indisputable risk factor for DE. Thus, dental examination should be recommended for diagnosed and suspected GERD patients46.

Figure 5: The Montreal classification of GERD. Text highlighted in red box indicates extraesophageal manifestations of the disease45. GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Despite of the important correlations between the two conditions, some clinicians still fail to appropriately diagnose patients with DE due to the heavily reliance on direct clinical observation which is considered an unreliable method for monitoring the rate of tooth wear by some47. Additionally, it is also important to remember that GERD is an intrinsic cause of tooth erosion and leads to the loss of enamel and dentin. This tooth structure loss leads to instability of the occlusion as teeth passively erupt (alveolar compensation) to maintain occlusion47. Thus, the intricate relationship between two conditions can only be managed through a holistic approach. Strikingly, dentist is often the first health care professional to diagnose systemic diseases through observations of oral manifestation and in case of GERD, DE and DH may be evident48. Dentist can help in early diagnosis of patients who have unexplained dental erosion and refer them to the gastroenterologist for further investigation. Collaboration effort between specialists during the diagnosing and managing of GERD would inevitably improve the patients’ medical and dental health49. Equally, patient education is paramount since dentist play a pivotal role in maintaining patient’s dental health (Figure 6). By simply making their patients aware of the repercussion related to acidic attack and irreversible dental damage, advice on potentially harmful drinks and food and about daily tooth brushing tips may make a difference to a patient’s dental health and quality of life12,48.

Figure 6: Recommendations to prevent dentine hypersensitivity12

References:

1. Antunes C, Aleem A, Curtis SA. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID: 28722967, 2023. 2. Zhang D, Liu S, Li Z, Wang R. Global, regional and national burden of gastroesophageal reflux disease, 1990-2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. Ann Med 2022; 54: 1372–84. 3. Faculty of Medicine CUHK. CUHK Succeeds in Treating Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease by Implantable Pulse Generator. 2015. 4. Ping-Yi Tan V, Wong BC, Wong WM, et al. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Cross-Sectional Study Demonstrating Rising Prevalence in a Chinese Population. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016; 50: e1–7. 5. Wu JCY, Sheu BS, Wu MS, Lee YC, Choi MG. Phase 4 Study in Patients From Asia With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Treated With Dexlansoprazole. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2020; 26: 85. 6. Richter JE, Rubenstein JH. Presentation and Epidemiology of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterology 2018; 154: 267–76. 7. Delshad SD, Almario C V., Chey WD, Spiegel BMR. Prevalence of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Proton Pump Inhibitor-Refractory Symptoms. Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 1250-1261.e2. 8. Katz PO, Dunbar KB, Schnoll-Sussman FH, Greer KB, Yadlapati R, Spechler SJ. ACG Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2022; 117: 27–56. 9. Liu XX, Tenenbaum HC, Wilder RS, Quock R, Hewlett ER, Ren YF. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity: An evidence-based overview for dental practitioners. BMC Oral Health 2020; 20: 1–10. 10. Robinson P, Baker S, Gibson B. Introduction. In: Dentine Hypersensitivity, 1st edn. Boston: Academic Press, 2015: 3–20. 11. Chu CH, Pang KKL, Lo ECM. Dietary behavior and knowledge of dental erosion among Chinese adults. BMC Oral Health 2010; 10: 1–7. 12. Chu CH, Lam A, Lo ECM. Dentin hypersensitivity and its management. Gen Dent 2011; 59: 115–22. 13. Addy M. Dentine hypersensitivity: New perspectives on an old problem. Int Dent J 2002; 52: 367–75. 14. Department of Health HK. Oral Health Survey 2021. Hong Kong SAR Government 2024. 15. Rees JS, Jin LJ, Lam S, Kudanowska I, Vowles R. The prevalence of dentine hypersensitivity in a hospital clinic population in Hong Kong. J Dent 2003; 31: 453–61. 16. Asimakopoulou K, West N, Davies M, Gupta A, Parkinson C, Scambler S. Why don’t dental teams routinely discuss dentine hypersensitivity during consultations? A qualitative study informed by the Theoretical Domains Framework. J Clin Periodontol 2024; 51: 118–26. 17. Ortiz ADC, Fideles SOM, Pomini KT, Buchaim RL. Updates in association of gastroesophageal reflux disease and dental erosion: systematic review. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 15: 1037–46. 18. Chakraborty A, Anjankar AP. Association of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease With Dental Erosion. Cureus 2022; 14. DOI:10.7759/CUREUS.30381. 19. Ali AST, Alhamdan FZ, Thabet FT, Alsuwaidan NK, Almontashri RM, Alanazi RM. Dental Erosion Prevalence and Risk Factor in Hypersensitive Patients. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2024; 16: S2470–2. 20. Idon PI, Sotunde OA, Ogundare TO. Beyond the Relief of Pain: Dentin Hypersensitivity and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life. Front Dent 2019; 16: 325. 21. Gibson BJ, Boiko OV, Baker SR, et al. The everyday impact of dentine sensitivity: Personal and functional aspects. Social Science and Dentistry 2010; 1: 11–20. 22. Baker SR, Gibson BJ, Sufi F, Barlow A, Robinson PG. The Dentine Hypersensitivity Experience Questionnaire: a longitudinal validation study. J Clin Periodontol 2014; 41: 52–9. 23. Mason S, Burnett GR, Patel N, Patil A, MacLure R. Impact of toothpaste on oral health-related quality of life in people with dentine hypersensitivity. BMC Oral Health 2019; 19: 1–11. 24. Health Partners Haleon. Understanding the Patient Psychology of Dentin Hypersensitivity. 2024. 25. Hu ML, Zheng G, Lin H, Yang M, Zhang YD, Han JM. Network meta-analysis on the effect of desensitizing toothpastes on dentine hypersensitivity. J Dent 2019; 88. DOI:10.1016/J.JDENT.2019.07.008. 26. Alonso RCB, Oliveira L de, Silva JAB, et al. Effectiveness of Bioactive Toothpastes against Dentin Hypersensitivity Using Evaporative and Tactile Analyses: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Oral 2024, Vol 4, Pages 36-49 2024; 4: 36–49. 27. Jang JH, Oh S, Kim HJ, Kim DS. A randomized clinical trial for comparing the efficacy of desensitizing toothpastes on the relief of dentin hypersensitivity. Sci Rep 2023; 13: 5271. 28. Pradeep AR, Agarwal E, Naik SB, Bajaj P, Kalra N. Comparison of efficacy of three commercially available dentifrices on dentinal hypersensitivity: a randomized clinical trial. Aust Dent J 2012; 57: 429–34. 29. Bae JH, Kim YK, Myung SK. Desensitizing toothpaste versus placebo for dentin hypersensitivity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol 2015; 42: 131–41. 30. Johannsen A, Emilson CG, Johannsen G, Konradsson K, Lingström P, Ramberg P. Effects of stabilized stannous fluoride dentifrice on dental calculus, dental plaque, gingivitis, halitosis and stain: A systematic review. Heliyon 2019; 5. DOI:10.1016/J.HELIYON.2019.E02850. 31. Fiorillo L, Cervino G, Herford AS, Laino L, Cicciù M. Stannous Fluoride Effects on Enamel: A Systematic Review. Biomimetics (Basel) 2020; 5: 1–22. 32. Hines D, Xu S, Stranick M, et al. Effect of a stannous fluoride toothpaste on dentinal hypersensitivity: In vitro and clinical evaluation. J Am Dent Assoc 2019; 150: S47–59. 33. Parkinson CR, Jeffery P, Milleman JL, Milleman KR, Mason S. Confirmation of efficacy in providing relief from the pain of dentin hypersensitivity of an anhydrous dentifrice containing 0.454% with or without stannous fluoride in an 8-week randomized clinical trial. Am J Dent 2015; 28: 190–6. 34. Du Min Q, Bian Z, Jiang H, et al. Clinical evaluation of a dentifrice containing calcium sodium phosphosilicate (novamin) for the treatment of dentin hypersensitivity. Am J Dent 2008; 21: 210–4. 35. Khijmatgar S, Reddy U, John S, Badavannavar AN, D Souza T. Is there evidence for Novamin application in remineralization? A Systematic review. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res 2020; 10: 87–92. 36. Mohammadipour HS, Bagheri H, Babazadeh S, Khorshid M, Shooshtari Z, Shahri A. Evaluation and comparison of the effects of a new paste containing 8% L-Arginine and CaCO3 plus KNO3 on dentinal tubules occlusion and dental sensitivity: a randomized, triple blinded clinical trial study. BMC Oral Health 2024; 24: 1–14. 37. Yang ZY, Wang F, Lu K, Li YH, Zhou Z. Arginine-containing desensitizing toothpaste for the treatment of dentin hypersensitivity: a meta-analysis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent 2016; 8: 1–14. 38. Douglas-de-Oliveira DW, Vitor GP, Silveira JO, Martins CC, Costa FO, Cota LOM. Effect of dentin hypersensitivity treatment on oral health related quality of life - A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2018; 71: 1–8. 39. Hu ML, Zheng G, Zhang YD, Yan X, Li XC, Lin H. Effect of desensitizing toothpastes on dentine hypersensitivity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2018; 75: 12–21. 40. Liu Y, Wu L, Meng FQ, Hou XS, Zhao J. [Effect of calcium sodium phosphosilicate and potassium nitrate on dentin hypersensitivity: a systematic review and Meta-analysis]. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2018; 36: 301–7. 41. Pollard AJ, Khan I, Davies M, Claydon N, West NX. Comparative efficacy of self-administered dentifrices for the management of dentine hypersensitivity - A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Dent 2023; 130. DOI:10.1016/J.JDENT.2023.104433. 42. FDI World Dental Federation. Fact Sheet For Non-Oral Health Professionals: Oral Hygiene. 2024. 43. Raising awareness of tooth wear and dentine hypersensitivity. Br Dent J 2016; 221: 593–593. 44. Dionysopoulos D, Gerasimidou O, Beltes C. Dentin Hypersensitivity: Etiology, Diagnosis and Contemporary Therapeutic Approaches—A Review in Literature. Applied Sciences 2023, Vol 13, Page 11632 2023; 13: 11632. 45. Pauwels A. Dental erosions and other extra-oesophageal symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: Evidence, treatment response and areas of uncertainty. United European Gastroenterol J 2015; 3: 166–70. 46. D’Agostino S, Bissoli A, Caporaso L, Iarussi F, Pulcini R, Dolci M. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and dental erosion: A modern review. Japanese Journal of Gastroenterology Research 2021; 1. DOI:10.52768/JJGASTRO/1003. 47. Chockattu SJ, Deepak BS, Sood A, Niranjan NT, Jayasheel A, Goud MK. Management of dental erosion induced by gastro-esophageal reflux disorder with direct composite veneering aided by a flexible splint matrix. Restor Dent Endod 2018; 43: e13. 48. Dundar A, Sengun A. Dental approach to erosive tooth wear in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Afr Health Sci 2014; 14: 481. 49. Alavi G, Alavi A, Saberfiroozi M, Sarbazi A, Motamedi M, Hamedani S. Dental Erosion in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) in a Sample of Patients Referred to the Motahari Clinic, Shiraz, Iran. J Dent 2014; 15: 33.