The disease burden of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) virus infection is substantial, about 257 million patients are infected, which contributes to approximately 1 million of deaths every year globally. While CHB can be manifested as an asymptomatic infection, it can result in severe liver diseases, including liver failure, cirrhosis and even hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)1. Thus, timely treatment suppressing hepatitis B virus (HBV) is of paramount importance. Practically, nucleos(t)ide analogues, including tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), and entecavir (ETV), have been proven to be effective in controlling CHB and are recommended as the first-line medications against CHB. Yet, the relative safety profiles and therapeutic effects of TAF, TDF, and ETV remain uncertain2. In the American Association for The Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) The Liver Meeting 2024, impactful findings comparing the clinical performance of TAF, TDF, and ETV were published, which provided insight into optimising CHB management.

While TAF, TDF, and ETV are recommended as the first-line therapy for suppressing HBV, clinical evidence demonstrating the relative efficacy of the medications would facilitate optimal treatment decisions. In this regard, a systematic review and meta-analysis, which included 27 studies involving 93,236 CHB patients, was conducted by Polpichai and co-workers3.

The meta-analysis indicated that the HCC incidence in TAF-treated patients was significantly lower than those treated with TDF (risk ratio [RR]: 0.4, p<0.00001) and ETV (RR: 0.55, p=0.03). In the sub-analysis of HCC risk between patients who received TAF and TDF according to race, TAF was demonstrated to yield lower HCC risk among Asians (RR: 0.39, p<0.0001) and in mixed race (RR: 0.42, p=0.02). Remarkably, similar findings between TAF and TDF were obtained in both previously treated and treatment-naïve patients3.

In the subsequent comparison between TDF and ETV, the results suggested that TDF-treated patients had a lower HCC incidence versus ETV-treated individuals (RR: 0.6, p<0.0001). Moreover, the observation was shown to be valid in both previously treated (RR: 0.68, p<0.0001) and treatment-naïve patients (RR: 0.58, p<0.00001)3.

While direct comparison of clinical performance between TAF, TDF, and ETV is limited, the meta-analysis by Polpichai et al., which covered a large pool of CHB patients, has provided high-quality evidence on the efficacy of the medications in controlling HCC risk. As per the results, TAF was associated with a lower HCC risk as compared to both TDF and ETV. Subsequently, TDF was demonstrated to yield a significantly lower HCC risk than ETV. Hence, the findings would hint physicians at making sensible choices among the recommended first-line therapies.

TDF has revolutionised the treatment of CHB for its potent antiviral properties. Nonetheless, its potential long-term impacts on the kidneys and bones have raised clinical concerns. Provided its substantially lower serum concentration, TAF allows a reduced off-target exposure to the drug in kidneys and bones and thus improves tolerability without compromising the antiviral efficacy4. Apart from kidneys and bones, a recent analysis of the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service Claims Database by Kim et al., involving 23,074 CHB patients, evaluated the liver-related outcomes upon TAF and TDF treatment5.

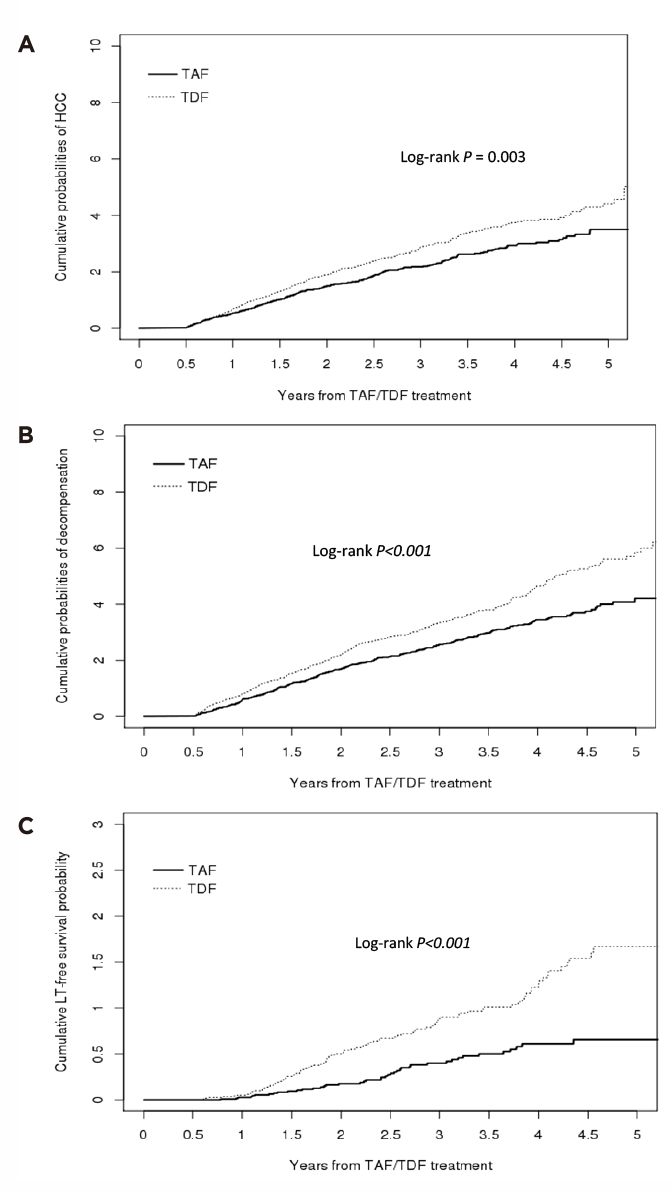

The results revealed that TAF treatment in patients with CHB (n=11,537) was associated with significantly lower risks of HCC (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.77, p=0.003, Figure 1A), liver transplantation or death (HR: 0.43, p<0.001, Figure 1B), and decompensation (HR: 0.74, p<0.001, Figure 1C) compared to TDF treatment. Interestingly, subgroup analysis according to the presence of liver cirrhosis in the study suggested that, in patients without cirrhosis, those treated with TAF have significantly lower risks of HCC (HR: 0.69, p=0.012), decompensation (HR: 0.73, p=0.003), and liver transplantation or death (HR: 0.3, p<0.001) compared to those treated with TDF. For those with cirrhosis, however, the TAF-treated group showed significantly lower risks of decompensation (HR: 0.75, p=0.011) and liver transplantation or death (HR: 0.55, p=0.012), but not the risk of HCC (p=0.063) relative to the TDF group5.

Figure 1. Cumulative incidence of liver-related clinical outcomes in CHB patients treated with TAF or TDF, A) HCC, B) liver transplantation or death, C) decompensation5

The results thus suggested that TAF is associated with better liver-related outcomes as compared to TDF, regardless of the presence of liver cirrhosis. Taking the potential impacts on the kidneys and bones of TDF into consideration, TAF would be the preferred treatment option in CHB management.

While both TAF and ETV are recommended first-line therapies for CHB management, a recent clinical study advocated that switching from ETV to TAF is safe and provides superior virological response and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) normalisation compared with continuing ETV monotherapy6. Accordingly, a multicentre, retrospective study by Li et al. compared the antiviral efficacy of TAF and ETV in treatment-naïve CHB patients.

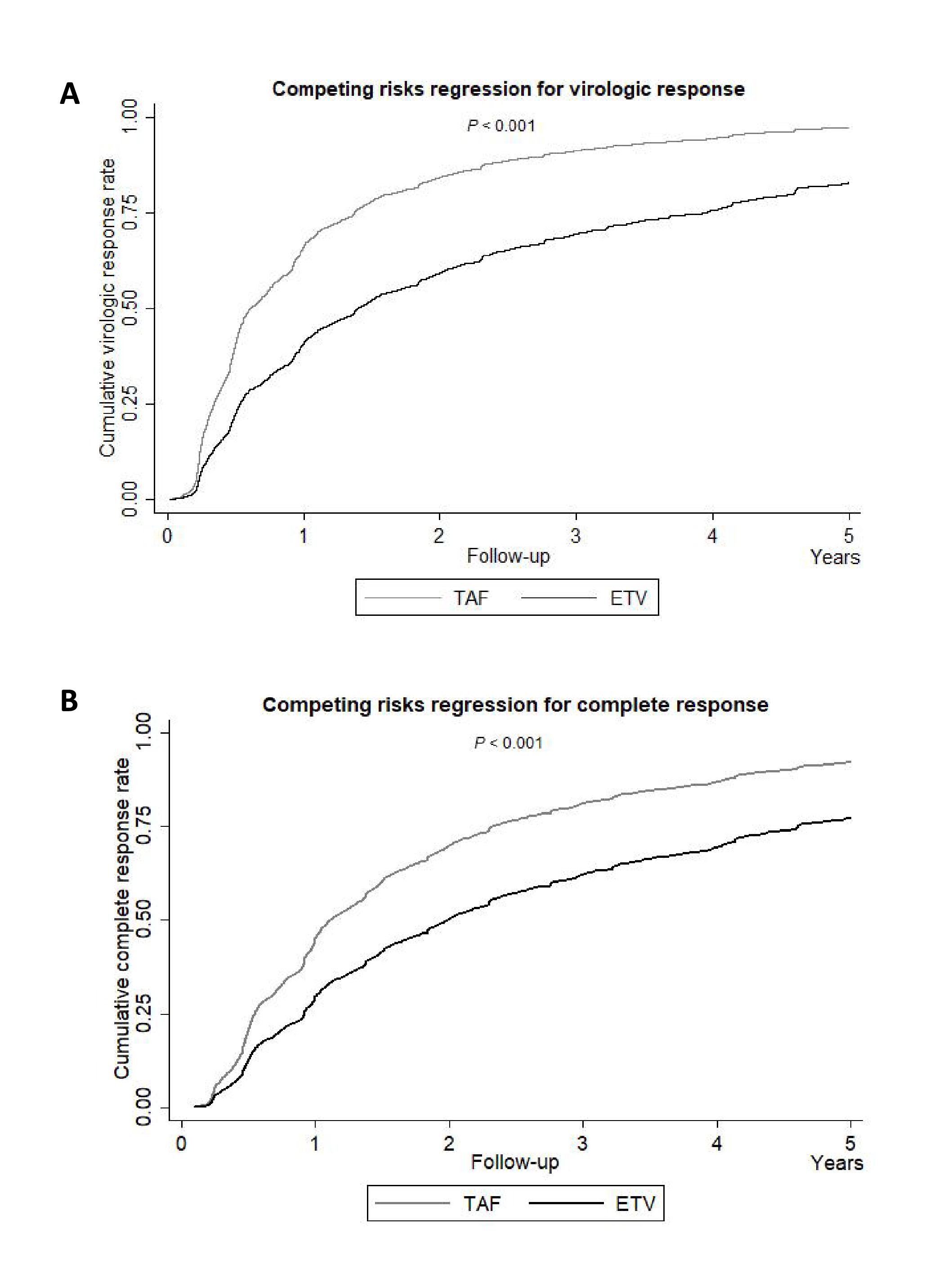

Among the 3,068 patients, 700 received TAF, and 2,368 received ETV. In the overall cohort, TAF demonstrated a superior 5-year rate of virologic response (VR, 97.4% vs 82.9%, p<0.001, Figure 2A) and complete response (CR, 92.3% vs 77.5%, p<0.001, Figure 2B) compared to ETV. Furthermore, when stratified by alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, both subgroups (i.e. ALT <2 x upper limit of normal [ULN] and ALT 2 x ULN) treated with TAF demonstrated significantly higher VR and CR rates over those treated with ETV7. By virtue of the notable advantage in VR and CR, regardless of ALT levels, TAF appears to offer better HBV suppression efficacy than ETV.

Figure 2. Competing risks regression for A) virologic response, B) complete response in TAF- and ETV-treated patients in overall cohort7

Apart from viral suppression efficacy, the preferred therapy for CHB management is expected to have a good safety profile and be well-tolerated. Particularly, the retrospective study by Wang et al., which recruited 190 CHB patients, assessed the impacts of TAF and ETV on renal function in the patients8.

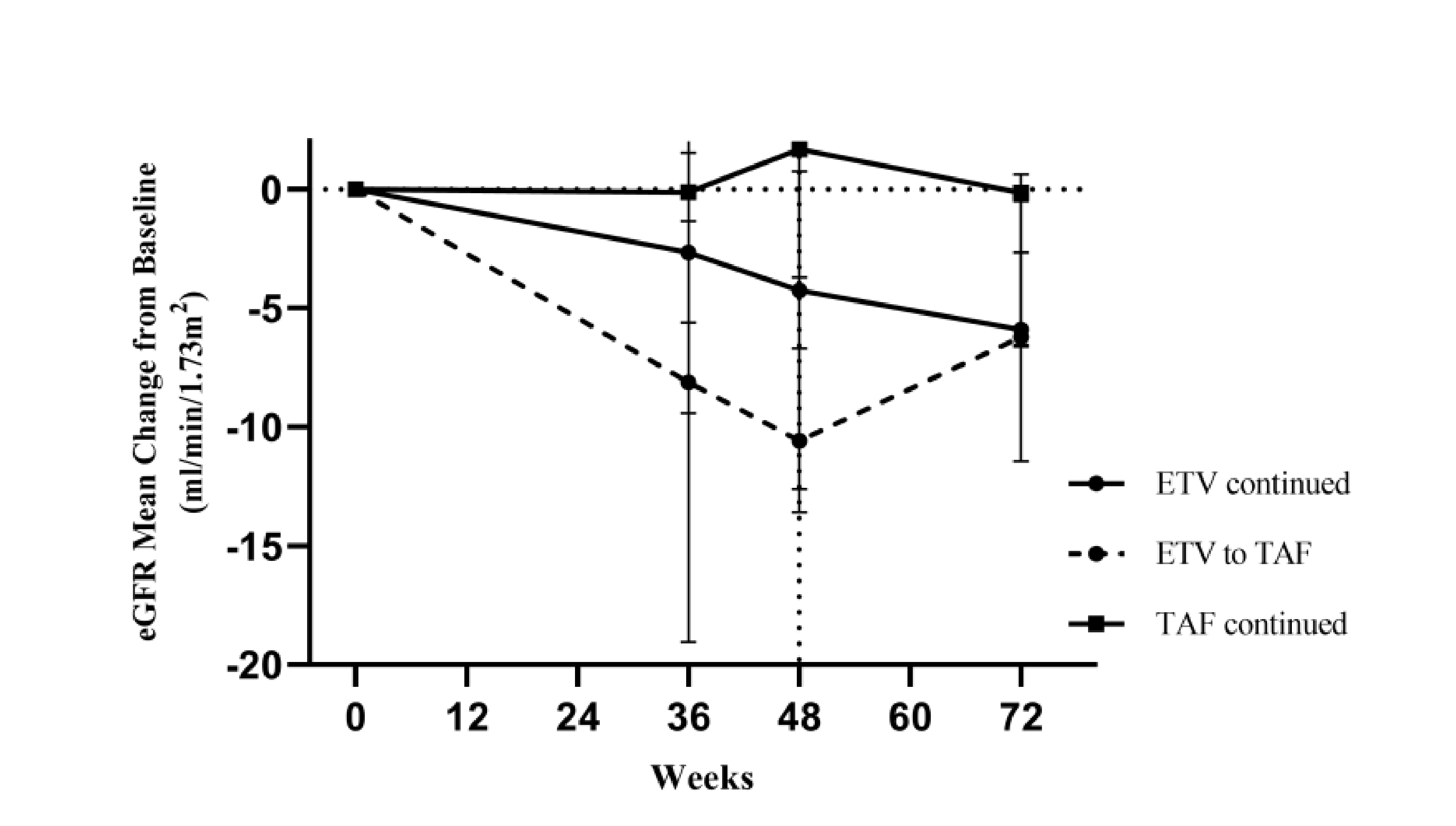

After 36 weeks of treatment, the mean estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of patients in the ETV group was significantly lower than that in the TAF group (109.93 ml/min/1.73m2 vs 115.12 ml/min/1.73m2, p=0.007). Essentially, both univariable and multivariable analysis reflected that antiviral regimens (ETV/TAF) were independently associated with renal abnormalities8.

In the study, 7 (9.21%) patients in the ETV group were switched from ETV to TAF due to eGFR abnormality at week 48. Remarkably, at 24 weeks post-switching, the mean eGFR value in this group increased from 87.84 ml/min/1.73m2 to 92.02 ml/min/1.73m2 (Figure 3), whereas the change in eGFR from week 48 to week 72 in patients switched from ETV to TAF was significantly larger than that continued ETV (p=0.015)8. Therefore, switching from ETV to TAF would likely result in substantial improvement in renal function among ETV-treated patients with eGFR abnormalities.

Based on the recent clinical findings above, TAF has been demonstrated to be more efficacious in reducing HCC risk than TDF and ETV. Besides, while having a lower risk of adverse impact on kidneys and bones, TAF was associated with a lower risk of liver-related outcomes compared to TDF. Compared with ETV, TAF was shown to be more effective in HBV suppression, with a lower impact on renal function. Essentially, TAF was demonstrated to improve renal function in ETV-treated CHB patients with renal abnormalities. Summarising data in published literature and the results reported at the AASLD The Liver Meeting 2024, TAF appears to be a plausible choice for the first-line treatment in CHB management, while switching from TDF or ETV to TAF could also be considered in cases of renal abnormalities.

Figure 3. Trends in eGFR change8

References

1. Peng W, Gu H, Cheng D, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus entecavir for treating hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure: real-world study. Front Microbiol 2023; 14: 1185492. 2. Ma X, Liu S, Wang M, et al. Tenofovir Alafenamide Fumarate, Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate and Entecavir: Which is the Most Effective Drug for Chronic Hepatitis B? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2021; 9: 335. 3. Polpichai N, Saowapa S, Jaroenlapnopparat A, et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk in Chronic Hepatitis B Patients Treated with Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF), Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (TDF), and Entecavir (ETV): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with GRADE Assessment. AASLD The Liver Meeting 2024; : 1246. 4. Hill A, Hughes SL, Gotham D, Pozniak AL. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate: is there a true difference in efficacy and safety? J Virus Erad 2018; 4: 72. 5. Kim S, Seo G, Han J, et al. Tenofovir Alafenamide Versus Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate In Chronic Hepatitis B: Liver-related Clinical Outcomes And Subgroup Analysis By Liver Cirrhosis Status. AASLD The Liver Meeting 2024; : 1215. 6. Li Z Bin, Li L, Niu XX, et al. Switching from entecavir to tenofovir alafenamide for chronic hepatitis B patients with low-level viraemia. Liver Int 2021; 41: 1254–64. 7. Li J, Chau A, Jun DW, et al. Antiviral Efficacy Of Tenofovir Alafenamide Versus Entecavir In Treatment-naïve Chronic Hepatitis B: A Multicenter Longitudinal Study. AASLD The Liver Meeting 2024; : 1417. 8. Wang L, Ma S, Liu L, Wan X, Zhang Y, Ge S. Renal Function Comparison Between Entecavir and Tenofovir Alafenamide in Treatment-naïve Chronic Hepatitis B. AASLD The Liver Meeting 2024; :1314.