Specialist in Haematology and Haematological Oncology

Department of Medicine & Geriatrics, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a clonal plasma cell disorder characterised by excess production of monoclonal immunoglobulins and light chains that can ultimately lead to specific end-organ damage1 . Notably, MM is the second most common haematologic malignancy and represents approximately 1% of all cancers2 . Patients with symptomatic myeloma are often treated with a combination of active agents, and eligible patients then proceed to high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). However, disease relapse invariably occurs post-ASCT. Therefore, different therapies have been employed post-transplantation as a maintenance treatment to improve progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS)3. Thus, to understand the role of maintenance treatment post-ASCT, we have invited Dr. Grace Lau, a specialist in Haematology and Haematological Oncology to share her expertise on the ever-changing treatment landscape of MM through a case-based sharing.

Decoding the Enigma of Multiple Myeloma

MM accounts for 1% of all cancers and approximately 10% of all haematologic malignancies4. The exact aetiology of MM is unknown5 . Chronic antigenic stimulation from infection, chronic inflammation6 and exposure to toxic substances (for instance, alcohol, insecticides) and radiation has been associated with an increased incidence of plasma cell myeloma7 . Furthermore, emerging studies have also suggested that obesity is associated with an increased risk of developing MM and may worsen the outcome for these patients; however, the causal relationship is not established8. MM is a disease of the elderly and its incidence increases with age. It is postulated that with the aging population, nearly 3 out of every 4 patients diagnosed with myeloma will be aged ≥ 659. Dr. Lau explained that apart from the aging population, MM is also more common in males than females10. She added that the racial and ethnic disparities is prevalent in MM, with non-Hispanic Black individuals being twice as likely to be diagnosed with MM compared with non-Hispanic White individuals11. Fortunately, over the last 10-20 years, the introduction of novel therapies has resulted in a deeper and more durable treatment responses in MM patients, resulting in long-term disease control with hope for a cure in the future12. Dr. Lau added that the change has been revolutionary with the availability of agents such as anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies13, proteosome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs such as lenalidomide14. Furthermore, the betterment complications and treatment-related adverse events15, according to Dr. Lau. For instance, the use of bone modifying agents has been shown to substantially reduce bone pain and skeletal events16. Vaccination, appropriate antimicrobial prophylaxis and the use of intravenous immunoglobulin markedly decrease the risk of infection in these immunocompromised patients17. It is of paramount importance to regularly review the patient's tolerability of the treatment since supportive care and dosing modification can effectively minimise treatment-related side effects, according to Dr. Lau.

Diagnostic Dilemmas in Multiple Myeloma

Considering the symptoms of MM being vague and nonspecific, early detection of the disease poses a serious diagnostic challenge in the primary care18. Dr. Lau elucidated that the diagnosis of MM requires ≥10% clonal bone marrow plasma cells or biopsy-proven bony or extramedullary plasmacytoma plus any of the myeloma-defining events, commonly known as CRAB which includes hypercalcaemia, renal failure, anaemia, or bony lesions, attributable to the underlying plasma cell disorder. Other myeloma-defining biomarkers include bone marrow clonal plasmacytosis ≥60%, serum involved/uninvolved free light chain (FLC) ratio ≥100 (provided involved FLC is ≥100 mg/L) and >1 focal lesion on magnetic resonance imaging4, which are "associated with roughly 80% probability of progression to MM within 2 years when present," according to Dr. Lau. She stated that the prognosis of patients newly diagnosed with MM (NDMM) relies on the molecular profile of the disease, along with other clinical risk factors, such as raised lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), elevated serum beta-2 microglobulin, hypoalbuminemia, primary refractory disease and extramedullary disease19.

Dr. Lau elaborated that MM symptoms are highly non-specific20, therefore, can be easily misdiagnosed as other medical conditions initially, leading to potential diagnostic delay. For instance, MM patients may first present with back pain and stiffness, which can easily be misattributed as arthritis21. Moreover, due to a lack of awareness of this condition in primary care, the attending physician may not immediately consider MM as a differential diagnosis, resulting in a delay in referring the patient for further investigations22. Additionally, differentiating various causes of vertebral collapse, based solely on X ray findings can be difficult and this can further contribute to a delay in diagnosis if appropriate follow-up examinations are not performed23. Thus, Dr. Lau advocated to seek specialist advice early if in doubt since this may help expedite the diagnosis and prompt the appropriate treatment for the patient.

Optimising Clinical Outcomes with Maintenance Treatment in MM

MM is incurable, and relapse is inevitable because of the residual disease24. Therefore, after ASCT, thalidomide maintenance therapy has often been implemented in the past since MM patients treated with thalidomide showed an improved PFS; however, due to treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) such as peripheral neuropathy, it is often difficult for MM patients to remain on thalidomide maintenance regimen24. Dr. Lau pointed out that MM patients with highrisk deletion of 17p treated with thalidomide often showed no survival benefit in terms of the OS25. Contrary to this, lenalidomide seems to be a better option as a maintenance therapy due to better patient tolerance and improved PFS after ASCT in MM patients compared to placebo26.

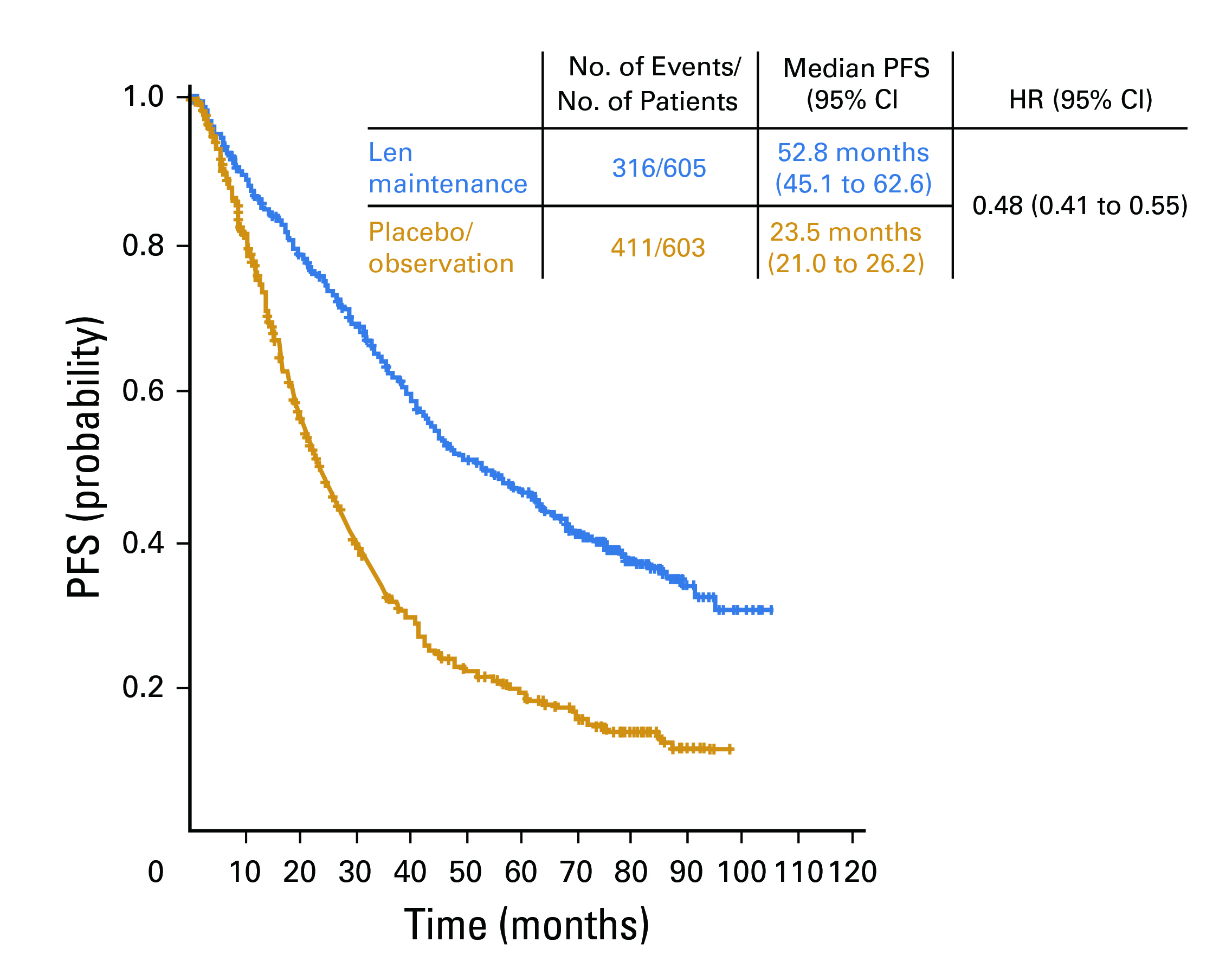

To illustrate the treatment benefits of lenalidomide, Dr. Lau shared the findings of a meta-analysis by McCarthy et al., (2017) with 1,208 intention-to-treat (ITT) population (605 NDMM patients in the lenalidomide maintenance group and 603 in the placebo or observation group). The median PFS (mPFS) was 52.8 months for the lenalidomide group and 23.5 months for the placebo or observation group (hazard ratio [HR] 0.48; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.41-0.55) (Figure 1)26.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier estimates of progression-free survival (PFS)26 . CI= confidence interval; HR= hazard ratio; Len= lenalidomide

Moreover, the cumulative incidence rate of progression or death as a result of myeloma was higher in the placebo or observation group compared to the lenalidomide maintenance group. The metaanalysis concluded that lenalidomide maintenance after ASCT in patients with NDMM demonstrated a significant OS benefit and PFS compared to placebo or observation26. Dr. Lau pointed out that MM patients at stage I and II of the international staging system (ISS) derive the most benefit with lenalidomide, compared to patients at stage III of the disease26.

Resilience of Lenalidomide in Real-World Clinical Practice

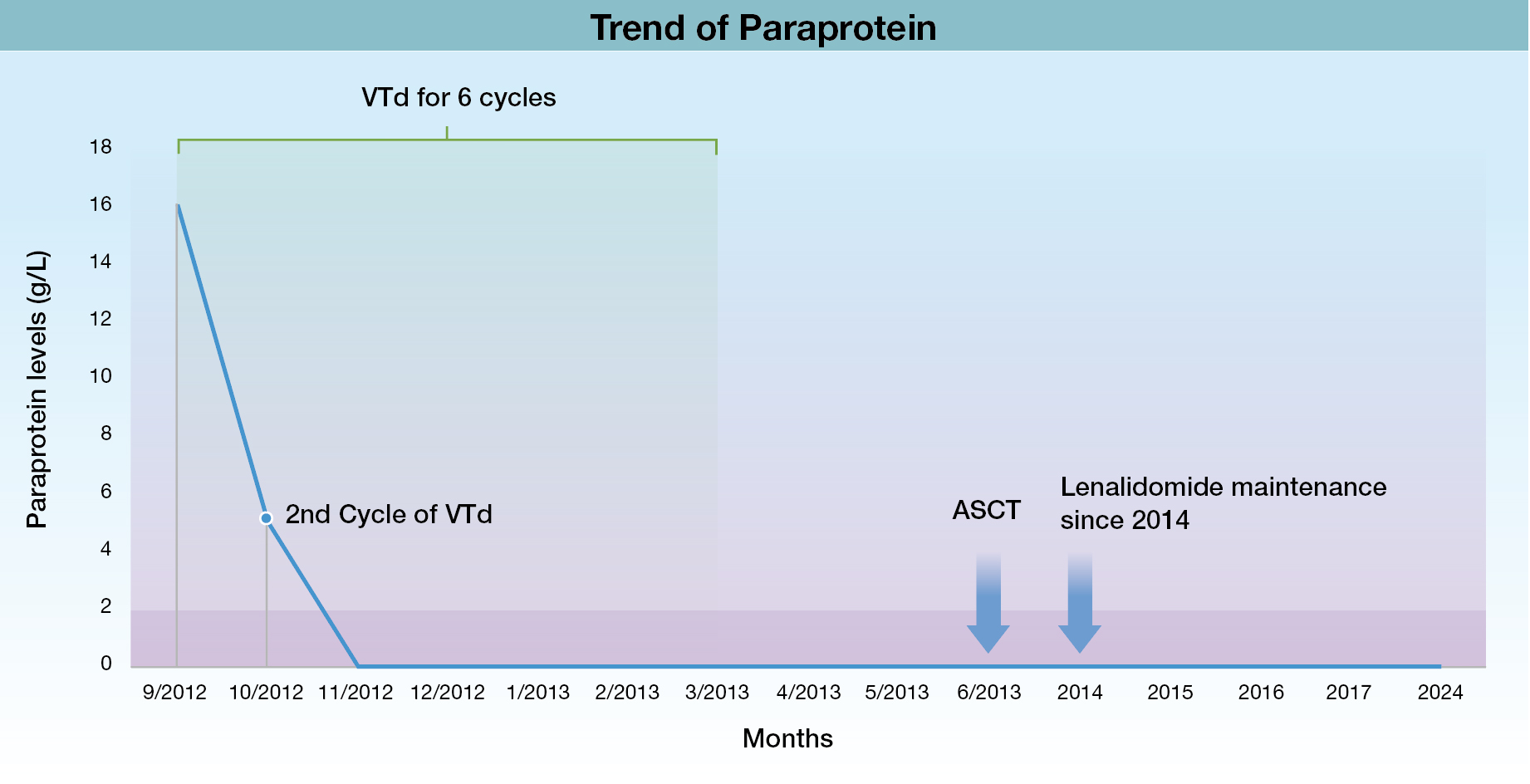

Lenalidomide has been approved as the first and only post- ASCT maintenance therapy since the 2017 after results from two phase III trials (IFM 2205-02 and CALGB 100104 trials) showed significant improvement in PFS, event-free survival and OS with lenalidomide maintenance compared to placebo27. Hence, to demonstrate its efficacy and safety in real-world clinical practice, Dr. Lau shared the case of a 59-year-old female who initially presented with generalised rib pain. Blood tests showed anaemia (haemoglobin [Hb] of 8.7g/dL), elevated levels of creatinine (180 umol/L) with hypercalcemia (3.32 mmol/L). Moreover, the skeletal survey revealed numerous lytic lesions over the ribs, cranial vault, pelvis, and the lumbar spine, in addition to fractured left 10th rib and partial collapse of T12 vertebra. Dr. Lau explained that the patient was eventually commenced on treatment after the diagnosis of MM and received 6 cycles of bortezomib, thalidomide and dexamethasone (VTd) from September 2012 to March 2013.

Remarkably, the patient was in complete remission (CR) only after receiving 2 cycles of VTd in November 2012 as indicated by the paraprotein levels in Figure 2 and stringent CR (sCR) was attained after the 3rd treatment cycle with VTd by the December 2012.

Figure 2. Trend of patient’s paraprotein provided by Dr. Lau.

Subsequently, the patient underwent ASCT following induction with VTd and was commenced on lenalidomide 10 mg maintenance following the cell count recovery post-ASCT. Strikingly, the patient remained in sCR since 2012 and only had neutropenia which was managed through dose adjustment. These findings have also been substantiated in a retrospective single-center analysis of adult MM patients that received upfront ASCT between 2005 and 2021, followed by single-agent lenalidomide maintenance28. A total of 1,167 patients were included with a median age of 61.4 years, and median follow-up of 47.9 months28. Interestingly, the median PFS and OS for the entire cohort was 56.6 months (95% CI: 48.2-61.4) and 111.3 months (95% CI: 101.7-121.5). The study concluded that the outcome with lenalidomide maintenance was comparable to those reported in larger clinical trial and longer duration of maintenance, even beyond 5 years, was associated with improved survival28.

Nevertheless, despite the therapeutic benefits of lenalidomide, the drug is not completely devoid of side effects. Haematological toxicity is common. Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia29 can be managed with the use of G-CSF, dose interruption and dose modification30. Furthermore, rash can occur in up to onethirds of the patients but is usually mild and rarely leads to treatment discontinuation31. Females of child-bearing potential and males should be advised to practise contraception because of the teratogenic potential of lenalidomide32. Notably, lenalidomide maintenance is associated with a slightly higher risk of secondary malignancy which warrants ongoing monitoring although the survival benefits outweigh risk33. With careful monitoring of these adverse events and appropriate interventions, majority of patients can be maintained on lenalidomide until the disease progression. In conclusion, lenalidomide is a stepping stone for keeping the disease at bay, representing the treatment revolution in MM.

References

1. Albagoush SA, et al. StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2024. 2. Tsang M, et al. Cancer 2019; 125(14): 2435-44. 3. Karam D, et al. Oncol Ther 2021; 9(1): 69-88. 4. Rajkumar SV. Am J Hematol

2022;97(8): 1086-107. 5. Devenney B, et al. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2004; 8(4): 401-5. 6. Jasiński M, et al. Front Immunol 2022; 13: 853540. 7. Durie BG. Semin Hematol 2001; 38(2 Suppl 3): 1-5. 8.

Tie W, et al. Pathol Oncol Res 2023; 29: 1611338. 9. Wildes TM, et al. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019; 67(5): 987-91. 10. Bird S, et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2021; 21(10): 667-75. 11. Peres LC, et al.

Blood Adv 2024; 8(1): 251-9. 12. Turesson I, et al. Eur J Haematol 2018. 13. Gozzetti A, et al. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022; 18(5): 2052658. 14. Alonso R, et al. Blood Adv 2020;4(10): 2163-71. 15.

Pozzi S, et al. Cancers (Basel) 2021; 13(19). 16. Hussain M, et al. Blood Rev 2023; 57: 100999. 17. Raje N, et al. Blood Cancer Journal 2023; 13(1): 116. 18. Goldschmidt N, et al. J Am Board Fam Med

2016; 29(6): 702-9. 19. Brigle K, et al. J Adv Pract Oncol 2022; 13(Suppl 4): 7-14. 20. Drayson M, et al. Br J Haematol 2024; 204(2): 476-86. 21. Khan S, et al. Springer International Publishing;

2023: 433-40. 22. Seesaghur A, et al. BMJ Open 2021; 11(10): e052759. 23. Kim IK, et al. Ann Coloproctol 2017; 33(2): 70-3. 24. Morgan GJ, et al. Blood 2012;119(1): 7-15. 25. Boyd KD, et al. Genes

Chromosomes Cancer 2011; 50(10): 765-74. 26. McCarthy PL, et al. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(29): 3279-89. 27. Hari P, et al. Future Oncology 2019; 15(35): 4045-56. 28. Pasvolsky O, et al. American

Journal of Hematology 2023; 98(10): 1571-8. 29. Song Z, et al. Front Pharmacol 2022; 13: 931495. 30. Harvey RD, et al. Blood 2011; 118(21): 1882-. 31. Tinsley SM, Kurtin SE, et al. Clin Lymphoma

Myeloma Leuk 2015; 15 Suppl: S64-9. 32. Semeraro M, et al. Oncoimmunology 2014; 3:e28386. 33. Nadeem O, et al. Cancers 2024; 16(5): 1023.