Editor-in-Chief, V·Pulse

Doctor at the National Health Services (NHS), United Kingdom (UK)

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, inflammatory, systemic autoimmune disease that initially affects small joints, and gradually involves larger joints with varying degree of severity. Apart from joint damage and bony erosion, pain is a common and often debilitating symptom reported by RA patients1. Essentially, RA-associated pain can be associated with psychological distress, and this may impair physical and social functioning, and increase healthcare utilisation. To counter RA-associated pain, a multimodal approach is taken that includes pharmaceutical agents, physical therapy, and patient education. Additionally, psychological interventions, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), has also shown to play an essential role in improving the well-being of RA patients in the setting of chronic or intermittent pain2. Thus, the aim of this article is to review the pathophysiology of RA-associated pain and to evaluate the clinical performance of current treatment against this phenomenon.

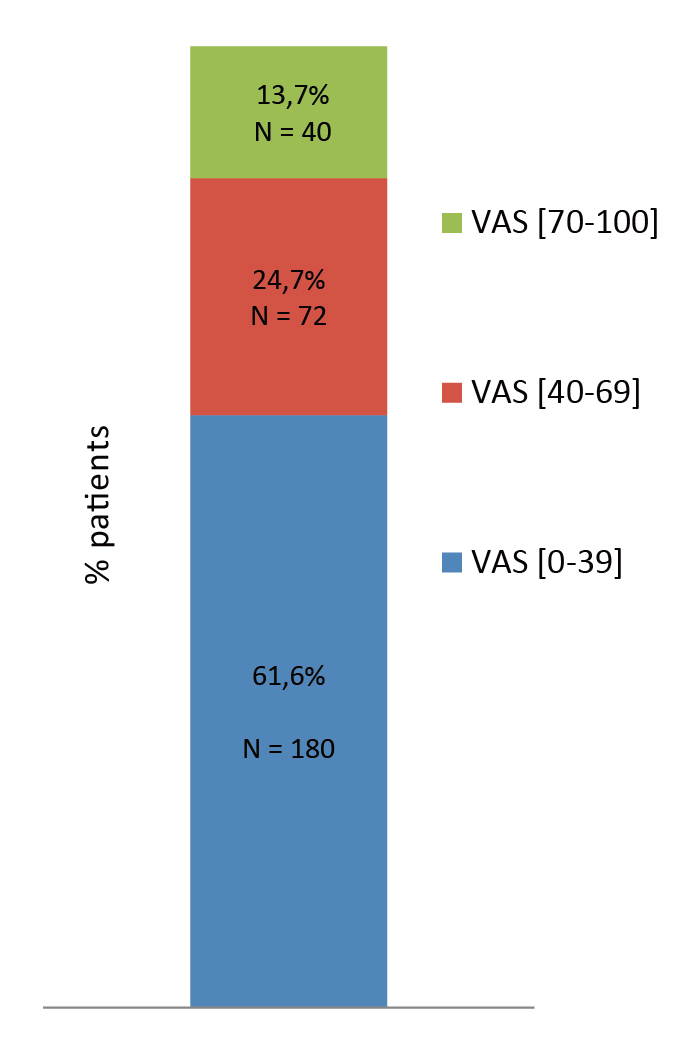

Pain is often debilitating and have detrimental effect on individual’s quality of life (QoL) across different aspects. The cross-sectional study by Vergne-Salle et al. (2020) reported 38.4% of 295 RA patients from 7 French rheumatology centres having a visual analogue scale (VAS) pain score greater than 40 mm/100 (Figure 1), though 83% of them were on biological treatment and 38.7% were in remission based on the RA activity score3. The findings thus highlighted that despite medications being prescribed, a substantial proportion of RA patients still experience relentless pain.

Figure 1. VAS pain score reported by RA patients3

In contrast to the early concepts, which hypothesised pain intensity being directly related to the amount of tissue injury, the contemporary view considered pain as a complex set of neural, humoral, and emotional events that involve the release of noxious mediators, inflammation, peripheral and central

sensitisation, as well as remodelling of synaptic contacts4.

In the context of RA, persistent pain is a complex and multifactorial phenomenon attributable to peripheral inflammation and sensitisation, as well as central pain mechanisms with central sensitisation3. In particular, inflammation and degenerative processes are the primary causes of pain, while inflammatory pain is commonly triggered within the joints during periods of active disease. In this regard, pain is a critical determinant of RA treatment outcomes. Nonetheless, it is crucial to appreciate that not all RA-associated pain affiliated to the active disease, instead non-inflammatory pain has also been reported5. For instance, fibromyalgia (FM) is a common disorder reported among RA patients, with about 12-48% of RA patients reported to have concurrent FM. Interestingly, patients with FM often report widespread and chronic pain. Furthermore, they may also have a lower threshold for the painful stimuli6.

Moreover, bone and cartilage destruction associated with RA may gradually lead to the development of secondary osteoarthritis, resulting in mechanical pain despite the patient having a disease remission or low disease activity. Although glucocorticoids (GCs) are often considered effective to alleviate inflammation and synovitis, long-term use of GCs has shown to be associated with numerous side effects, including infection, diabetes, hypertension, adrenal insufficiency, and osteoporosis. Additionally, GCs are also reported to indirectly contribute to non-inflammatory pain by causing changes in body habitus and mood disturbances5.

Providing inflammation is not the sole cause of RAassociated pain, RA treatment traditionally aimed to decrease inflammation and achieving remission may not address the existing adverse impacts of RA has on patient’s lives. In contrast, attention to non-inflammatory targets of pain management and psychosocial support is also paramount.

According to the RA Impact of Disease (RAID) study (2009), which involved 96 patients from 10 European countries, pain was selected by the respondents as the most important domain to be included in the calculation of the RAID score, which is a patient-derived weighted score utilised to assess the impact of RA. The study suggested that pain was a concern in 21% of the respondents, followed by functional disability (16%), fatigue (15%), emotional well-being (12%), sleep (12%), coping (12%) and physical well-being (12%)7.

It has been well-established that RA makes patients less independent and often interferes with their daily activities, such as working, participating in hobbies, and receiving support, thereby reducing their QoL. RA patients with more pain tend to experience loss of leisure-time activities. Not surprisingly, sexual dysfunction is also prevalent among RA patients since joint stiffness and fatigue may make it difficult for RA patients to engage in sexual activities8, further worsen propounded by pain, which may then lead to a reduce libido9, indirectly having negative impact on their QoL and relationships.

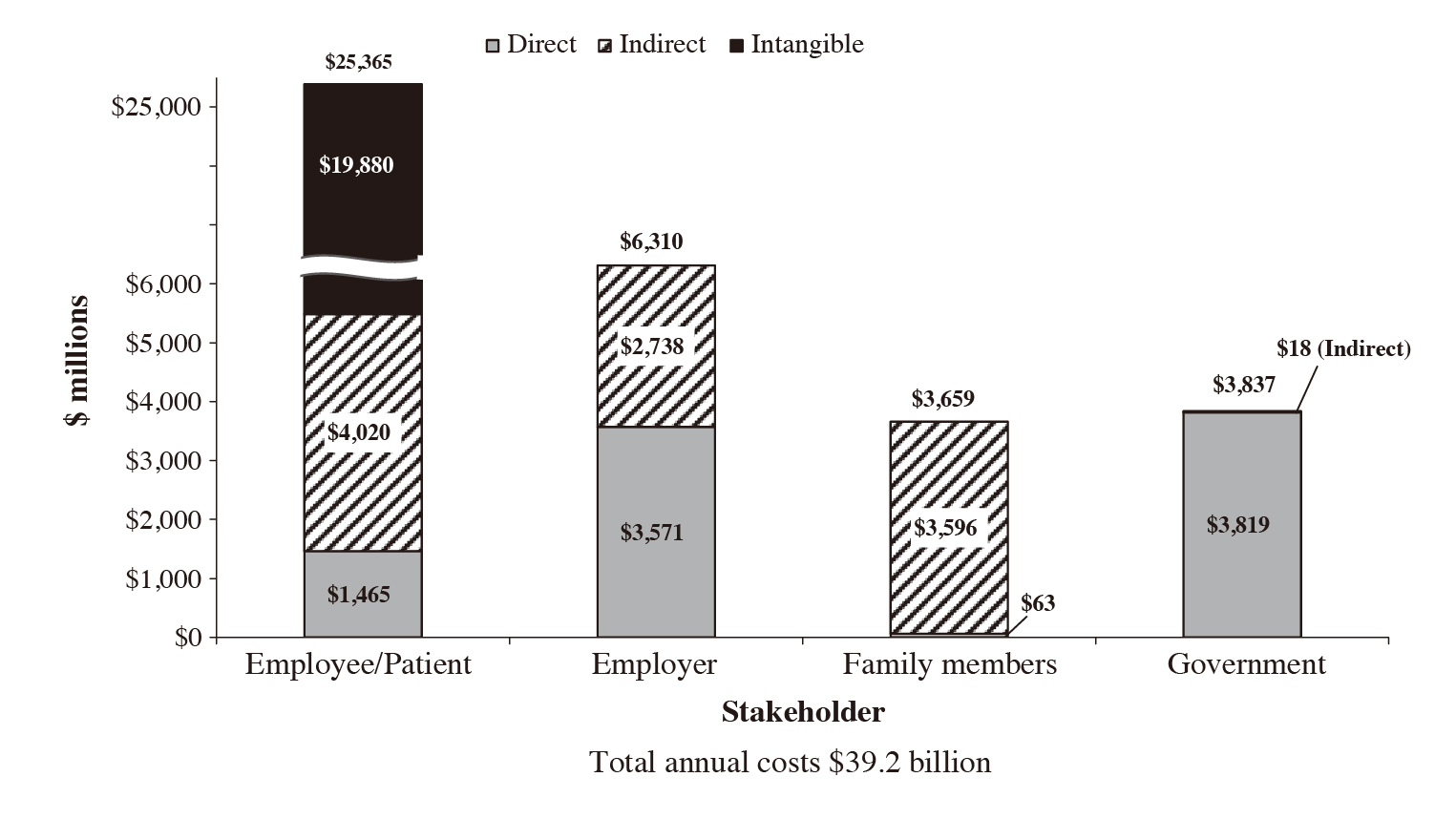

Of importance, RA-related disability causes a substantial loss of income to the individual and society at large. Birnbaum et al. (2010) estimated that the annual excess healthcare costs of RA patients mounted to around $8.4 billion, and costs of other RA-related issues around $10.9 billion in the United States (U.S.), whereas 33% of the total cost was allocated to employers, 28% to patients, 20% to the government, and 19% to caregivers (Figure 2). With the intangible costs of QoL deterioration and premature mortality, the total societal costs of RA were $39.2 billion (in 2005 dollars)10.

Figure 2. Annual societal costs of RA ($ millions)10

More recently, an estimation of the economic burden of RA in the U.S. reported by Poudel et al. (2023) indicated that the average annual total direct cost per person of RA patients using disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) has almost doubled ($24,729 to $45,867) from 2008-09 to 2018-19), while the expenditure on medications was a key driver for the increase in economic burden11.

Mental impacts, pain, fatigue, and early morning stiffness (EMS) predominantly affect QoL in RA patients, as well as contribute to high disease activity and are likely to predispose RA patients to depression. Interestingly, cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), and interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), are not only involved in the pathogenic mechanism of depression but also in pain and fatigue. In this regard, RA patients treated with anti-IL-6 disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) show an improvement in pain and fatigue, with lower levels of depression12.

Mood disorders, like depression and anxiety, have been incriminated as potential factors for relapse periods in RA patients, and they significantly alter the way patients perceive their current health. Notably, pain catastrophising is a psychological response characterised by an exaggerated perception of the pain's threat. Patients suffering from the condition tend to anticipate the worst outcomes, ruminate on pain-related thoughts, and expect their pain to persist or intensify. Pain catastrophising has been suggested to increase distress and amplify pain sensitivity13.

By virtue of the broad scope of adverse impacts of RA, holistic management has to be implemented for RA patients in addition to the treat-to-target pharmacological treatment for symptom control.

Given there is no cure for RA, the treatment goals often rely on reducing joint inflammation and pain, maximising joint function, and avoiding joint destruction and deformity14. According to the consensus recommendations addressed by the Hong Kong Society of Rheumatology (HKSR), methotrexate (MTX) should be the first-line therapy unless contraindicated, whereas leflunomide or sulfasalazine may be considered as initial conventional synthetic DMARD (csDMARD) therapy if MTX is contraindicated or not tolerated by the patient15.

If no clinical response to the first csDMARD is observed in 3 months or the treatment target is not reached in 6 months, adjustment of DMARD therapy is indicated. Moreover, when the treatment target cannot be achieved with MTX or other csDMARDs, the add-on of biological DMARDs (bDMARDs) or targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs) may be considered in the presence of poor prognostic factors of RA. Of note, the recommendation suggested that systemic GC as bridging therapy should be avoided when a new b/tsDMARD is initiated due to the increased risk of infection15.

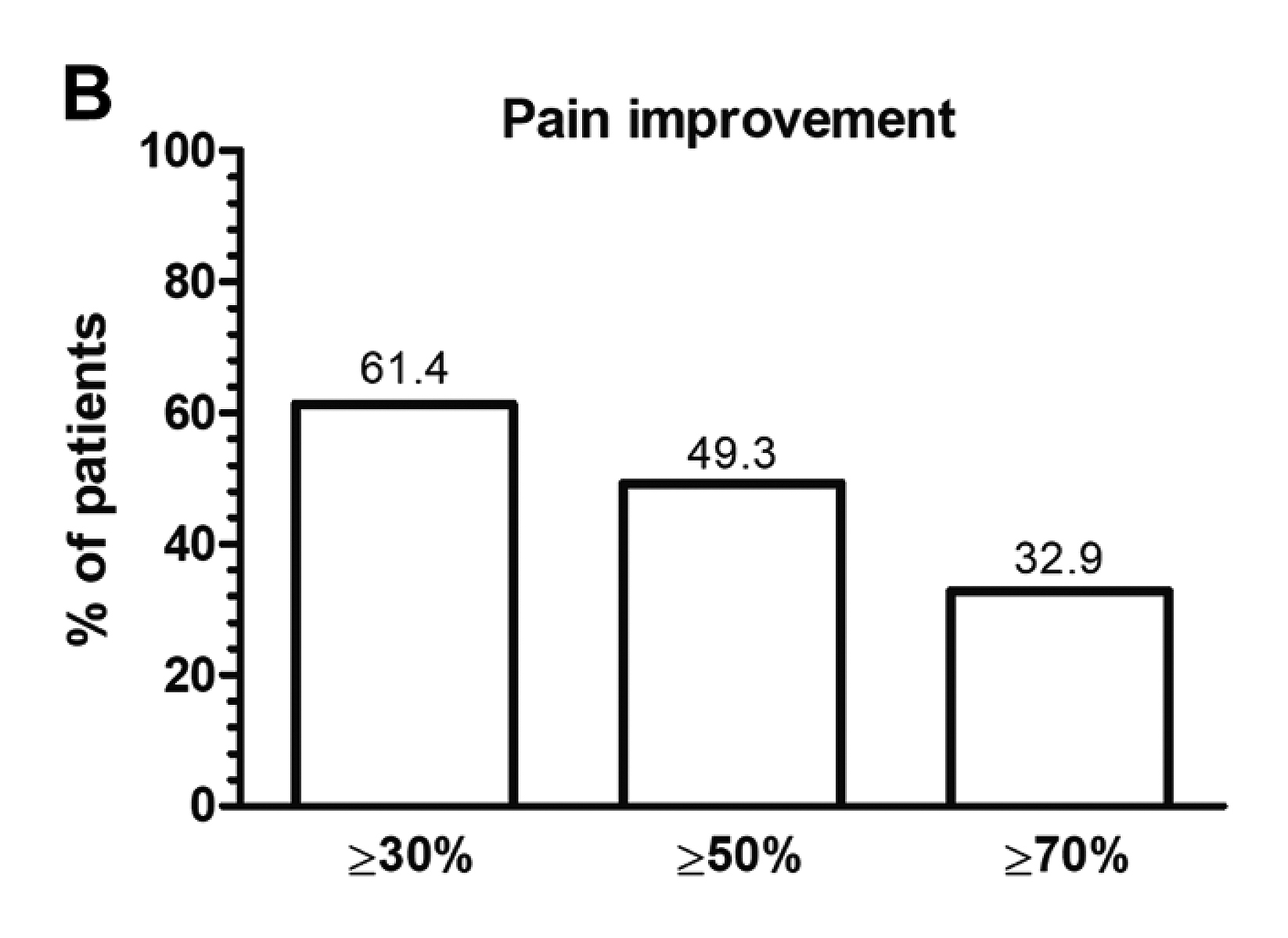

In the pharmacological management of RA pain, Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) have demonstrated promising efficacy in pain relief in previous clinical studies. For instance, the recent prospective cohort study by De Stefano et al. (2023), involving 181 RA patients initiated on JAKi therapy, demonstrated that the proportion of patients who achieved ≥30%, ≥50% and ≥70% pain improvement (VAS pain score) at 24 weeks was 61.4%, 49.3% and 32.9%, respectively (Figure 3). Furthermore, 40.6% and 28.5% of the patients achieved thresholds of remaining pain equivalent to mild pain or no/limited pain. The results also reported that pain improvements were more evident in patients naive to previous biologics16. Based on these findings, JAKi was confirmed effective in relieving pain in RA patients.

Figure 3. Percentage of patients who achieved pain relief thresholds with JAK inhibitor treatment16

In addition to pharmacological treatment, physical modalities, such as therapeutic exercises, may help to improve strength, endurance, mobility, and pain relief, and thus are essential components of rehabilitation care for rheumatic disorders. Notably, many RA patients avoid performing physical activities due to the fear of worsening pain or pressure on joints, which leads to decreased muscle strength and, ultimately, disability. Therefore, encouraging RA patients to perform physical activities as appropriate remains vital.

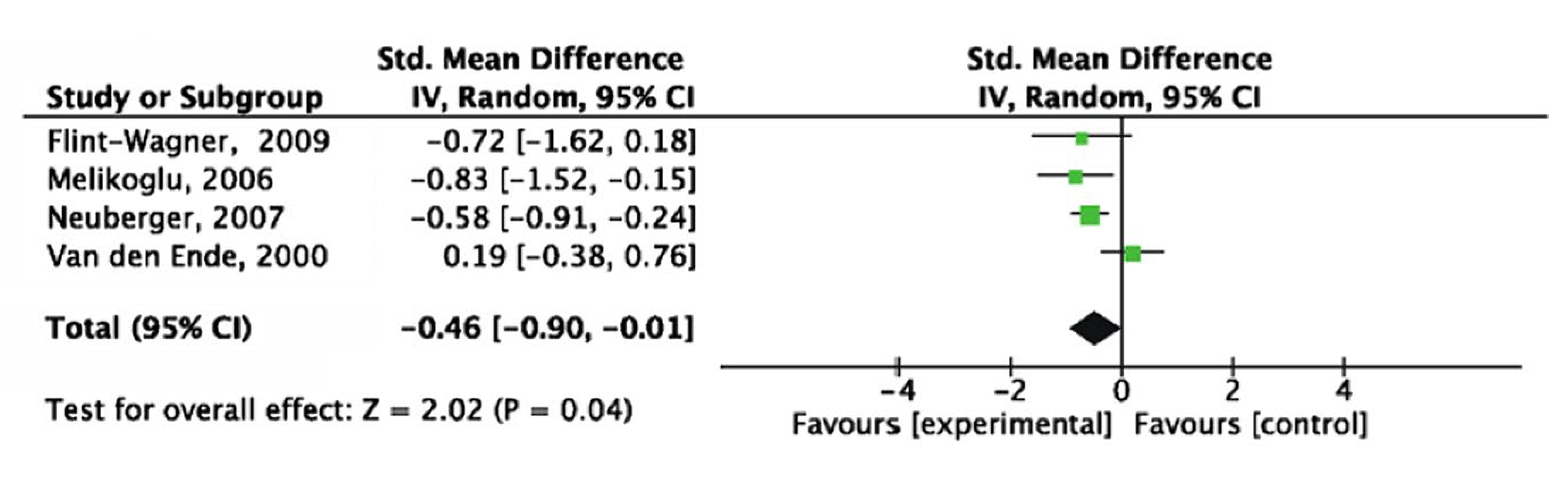

The benefits of exercise therapy in improving outcomes and pain relief in RA patients are well-established. A recent meta-analysis of 13 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), accounting for 967 RA patients, by Ye et al. (2022) indicated that aerobic exercise significantly improved functional ability (mean difference [MD]: − 0.25, p=0.0002), increased aerobic capacity (MD: 2.41, p <0.00001) and improved the Sit-to-Stand test score (MD: 1.60, p=0.04). Importantly, the results further indicated that the pain score obtained from the aerobic exercise group was significantly lower than that of the control group (standard mean difference [SMD]: − 0.46, p=0.04, Figure 4)17.

Figure 4. Forest plot of influence of aerobic exercise interventions on pain score17

Apart from physical exercises, manipulation has been shown to decrease joint pain and normalise function. Nonetheless, the exact mechanism of action of this treatment remains elusive, though it has been postulated to relieve pain by correcting muscle imbalance. Besides, stretching techniques are also advocated to increase flexibility, reduce the risk of injury, as well as relieve joint and myofascial pain18.

While heat and cold therapies, with thermal packs or water baths, are commonly used physical modalities for improving joint flexibility and pain relief, electrical stimulation of the nerves, muscles, or both has been considered for the pain management as well. By passing direct current (DC) across the painful area, both nociceptors and slow fibres that mediate pain are suppressed. Practically, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) has gained popularity since the devices are portable18.

As a complex spectrum of musculoskeletal conditions is involved in RA, managing RA pain obviously requires the physiotherapeutic approach alongside pharmacological treatment. Thanks to the continuous research and development of integrative approaches in RA management, diverse physical therapy modalities have emerged as a cornerstone in alleviating pain and restoring daily function for patients.

Provided the impacts of RA are often multidimensional, the holistic approach to the disease undoubtedly has to take both physiological and psychosocial aspects into account. Notably, there are numerous clinical data confirming psychological therapy as efficacious for RA patients in improving both physical and psychological functioning. More specifically, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has ushered a new era by becoming the most efficacious treatment for pain management in RA2.

Practically, the pain and functional disability module of CBT for RA patients may consist of progressive relaxation, attention diversion, stimulation of physical exercising in daily life in the face of the current physical condition, activity pacing, problem-solving, adjustment of goal setting, identification of pain-provoking cues in daily life, and cognitive restructuring of dysfunctional pain cognitions19. Ultimately, CBT helps patients develop a more realistic and balanced attitudes toward their disease.

A recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) by Omidvar et al. (2024), which included 36 RA patients, demonstrated that individuals receiving 8-sessions of CBT (n=21) had their pain self-efficacy scores significantly improved compared to the control group (n=15, Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire [PSEQ] score at follow-up: 35.62 [CBT] vs. 14.23 [control], p <0.001)20.

Besides CBT, patient education is also an intervention aimed to assist RA patients to strengthen their life and health management. Previous studies suggested that educational interventions can increase RA patients’ disease awareness and treatment options, thereby improving their adherence to treatment21. Remarkably, a recent meta-analysis of 24 RCTs on patient education for RA by Wu et al. (2022) evaluated the effectiveness of patient education on psychological status and clinical outcomes in RA. The outcome measures in the study included pain, physical function, disease activity, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), anxiety, depression, arthritis self-efficacy (ASE), and general health22.

The results revealed a statistically significant overall effect in favour of patient education for physical function, disease activity, ASE (pain, other symptoms, and total), and general health. Health education for RA patients may have a positive impact on the perception of pain and the disease management. Active participation in educational interventions facilitate the transformation of knowledge about disease and methods of preventing pain into changes in health behaviour. This results not only in pain relief and reduced disability but also in the improvement in body function22.

This article briefly reviewed the adverse impacts of RA and the associated pain on patients and society. Furthermore, to restrict the disease burden, a holistic approach, including pharmacological treatments, physical therapies, psychological interventions, and patient education, is often required. When considering the ultimate goal of RA management, the wellness practices proposed by Taylor and co-workers (2021) is undeniably noteworthy. Wellness can be regarded as a multi-dimensional, holistic concept encompassing lifestyle, environment, mental and spiritual well-being. At the same time, wellness practices often include exercise, optimised sleep, optimised nutrition, mindfulness, social connectedness, and positive emotions23. Optimising these aspects may help RA patients to improve their overall health status. Thus, it is desirable to consider wellness practices in addition to treat-to-target pharmacological agents for the holistic management of RA patients.

References

1. Walsh et al. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2014; 10: 581–92. 2. Sharpe. J Pain Res 2016; 9: 137–46. 3. Vergne-Salle et al. Eur J Pain 2020; 24: 1979–89. 4. Fitzcharles et al. Lancet 2021; 397: 2098–110. 5. Chancay et al. Women’s Midlife Health 2019 5:1 2019; 5: 1–9. 6. Gist et al. Int J Rheum Dis 2018; 21: 639–46. 7. Gossec et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2009; 68: 1680–5. 8. Dorner et al. Rheumatol Int 2018; 38: 1103. 9. Abdel-Nasser and Ali. Clin Rheumatol 2006; 25: 822–30. 10. Birnbaum et al. Curr Med Res Opin 2010; 26: 77–90. 11. Poudel et al. Value in Health 2023; 26: S127. 12. Ionescu et al. Medicina 2022, Vol 58, Page 1637 2022; 58: 1637. 13. Wilk et al. Rheumatology International 2024 44:6 2024; 44: 985–1002. 14. Bullock et al. Medical Principles and Practice 2019; 27: 501. 15. Ho et al. Clin Rheumatol 2019; 38: 3331–50. 16. De Stefano et al. Intern Emerg Med 2023; 18: 1733. 17. Ye et al. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 2022; 14: 1–15. 18. Mohapatra et al. Cureus 2023; 15. DOI:10.7759/CUREUS.51416. 19. Evers et al. Pain 2002; 100: 141–53. 20. Omidvar et al. Journal of Assessment and Research in Applied Counseling (JARAC) 2024; 6: 144–51. 21. Zangi et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74: 954–62. 22. Wu et al. Front Psychiatry 2022; 13: 848427. 23. Taylor et al. RMD Open 2021; 7. DOI:10.1136/RMDOPEN-2021-001959.

Answers for CME quiz of Feature Story of Issue 25: 1.C, 2.B, 3.B, 4.C, 5.C