Specialist in Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Director, Medical Data Analytics Centre (MDAC)

President, The Hong Kong Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (HKASLD)

Deputy Director, Center for Liver Health

Assistant Dean (Learning Experience), Faculty of Medicine

Professor, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

With the widespread implementation of vaccination programs and the development of potent antiviral therapies against chronic hepatitis B (CHB) virus infection in recent decades, the risk of horizontal and vertical transmission is decreasing. Accordingly, newly referred CHB patients are generally older and more often afflicted by various comorbidities1. Given that CHB patients may need long-term antiviral treatment to achieve optimal viral suppression, long-term safety would be a concern in the presence of comorbidities. In the symposium titled “Challenges and Strategies for Managing CHB Patients with Comorbidities”, organised by the Macao Society of Gastroenterology and Hepatology on 5th March 2024, Prof. Grace Lai-Hung Wong and Dr. Jimmy Che-To Lai highlighted the various impacts of comorbidities in CHB and discussed the essentials in the pharmacological management of CHB patients with comorbidities.

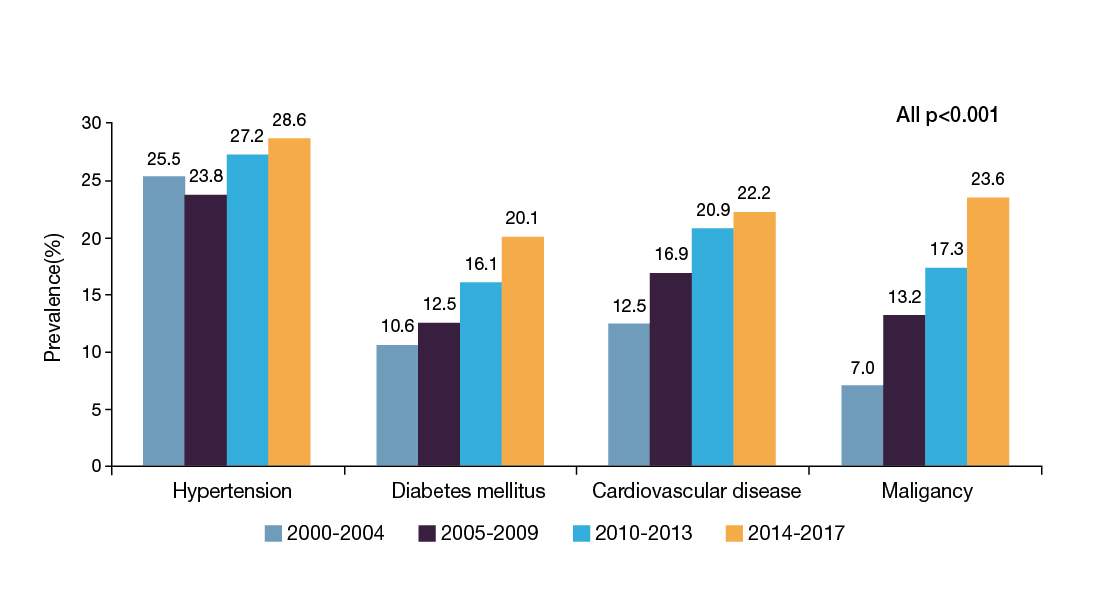

According to a territory-wide study in CHB patients Hong Kong during 2000-2017, increasing trends in the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), cardiovascular disease (CVD), and malignancy, were observed (all p<0.001, Figure 1)2. Prof. Wong explained that the increasing prevalence of common comorbidities is associated with the advancing age of the patients. She added that various metabolic syndromes, such as hypertension and DM, were prevalent regardless of CHB status3.

Figure 1. Prevalence of comorbidities in CHB patients2

Apart from the rising prevalence in CHB patients, comorbidities also increase the risk of a wide range of adverse outcomes. For instance, a former study by Prof. Wong’s team (2014) involving 1,466 CHB patients suggested that coincident metabolic syndrome would increase the risk of liver fibrosis progression while the effect was independent of viral load and hepatitis activity4. Remarkably, the risk of probable cirrhosis in CHB patients who had metabolic syndrome could be 5 times higher than those who did not5.

Prof. Wong highlighted that obesity would increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) among CHB patients. A prospective study of 2,903 male hepatitis B virus (HBV) carriers reported that being overweight or obese was associated with increased risk of HCC and liver-related mortality compared to normal-weight people6.

HCCs in patients with metabolic syndrome often developed in the absence of significant fibrosis7. Wong et al. (2012) reported that non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is found in over a quarter of the general adult Chinese population in Hong Kong8. Essentially, a meta-analysis of 34 studies with 68,268 CHB patients by Mao et al. (2023) indicated that hepatic steatosis was associated with an increased risk of HCC (odds ratio [OR]: 1.59) and cirrhosis (OR: 1.52)9.

Dr. Lai highlighted that a high glycaemic burden and a longer duration of DM is associated with the increased risk of fibrosis progression and HCC10. Importantly, a recent analysis using a territory-wide database in Hong Kong by Yip et al. (2022) showed that HCC risk scores were less predictive in CHB patients with DM than in non-DM patients11

According to a study by Buti et al. (2014), which followed 351 CHB patients treated with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) for 240 weeks, the proportion of patients achieved regression in liver cirrhosis was significantly less among patients with hepatic steatosis than those non-obese or without steatosis. The result further indicated that body-mass index (BMI) was the strongest negative predictor of cirrhosis regression, whereas steatosis at baseline correlated with the decreased regression of cirrhosis12.

DM and hypertension are well-established risk factors contributing to chronic kidney disease (CKD)13. In contrast, a meta-analysis by Fabrizi et al. (2017) suggested that HBV infection is possibly associated with the risk of developing a reduced glomerular filtration rate in the general population (adjusted HR: 2.22)14. Accordingly, Prof. Wong added that the prevalence of CKD among CHB patients also increased with age15.

In the phase III 108/110 studies, which included CHB patients treated with either TAF (n=866) or TDF with rollover to open-label TAF at week 96 (n=207) or week 144 (n=225), CHB patients with known risk factors for CKD showed smaller declines in their CKD stage with tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) versus TDF16.

While both entecavir (ETV) and TAF are the preferred therapeutics in patients with predisposing factors for nephrotoxicity, a retrospective cohort study by Jung et al. (2022) indicated that the risk of progression in CKD stage ≥1 was significantly higher in patients treated with ETV than TAF (Figure 2)17. Remarkably, Sriprayoon et al. (2017) evaluated the efficacy and safety of ETV and TDF in nucleoside-naïve CHB patients. While both therapeutics showed potent antiviral activity against HBV, reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was observed in both groups18. Thus, the decline in kidney function upon ETV treatment is noteworthy.

Figure 2. Cumulative incidence of progression in CKD stage ≥117

The long-term use of TDF is associated with a reduction in bone mineral density (BMD) and an increase in bone metabolism biomarkers. Recently, Yip et al. (2024) compared the impact of TDF with ETV on the fracture risk in elderly CHB patients. The analysis included 41,531 CHB patients identified using a territory-wide database in Hong Kong who received ETV (n=39,897) and TDF (n=1,634). At a median follow-up of 25.3 months, the risk of incident fracture in TDF-treated patients was significantly higher than ETV after 24 months (p=0.019). Essentially, patients with incident fractures were more likely to have DM, hypertension, congestive heart failure, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, and a history of fracture19. Hence, comorbidities have to be considered when selecting treatment for CHB patients, particularly elderly.

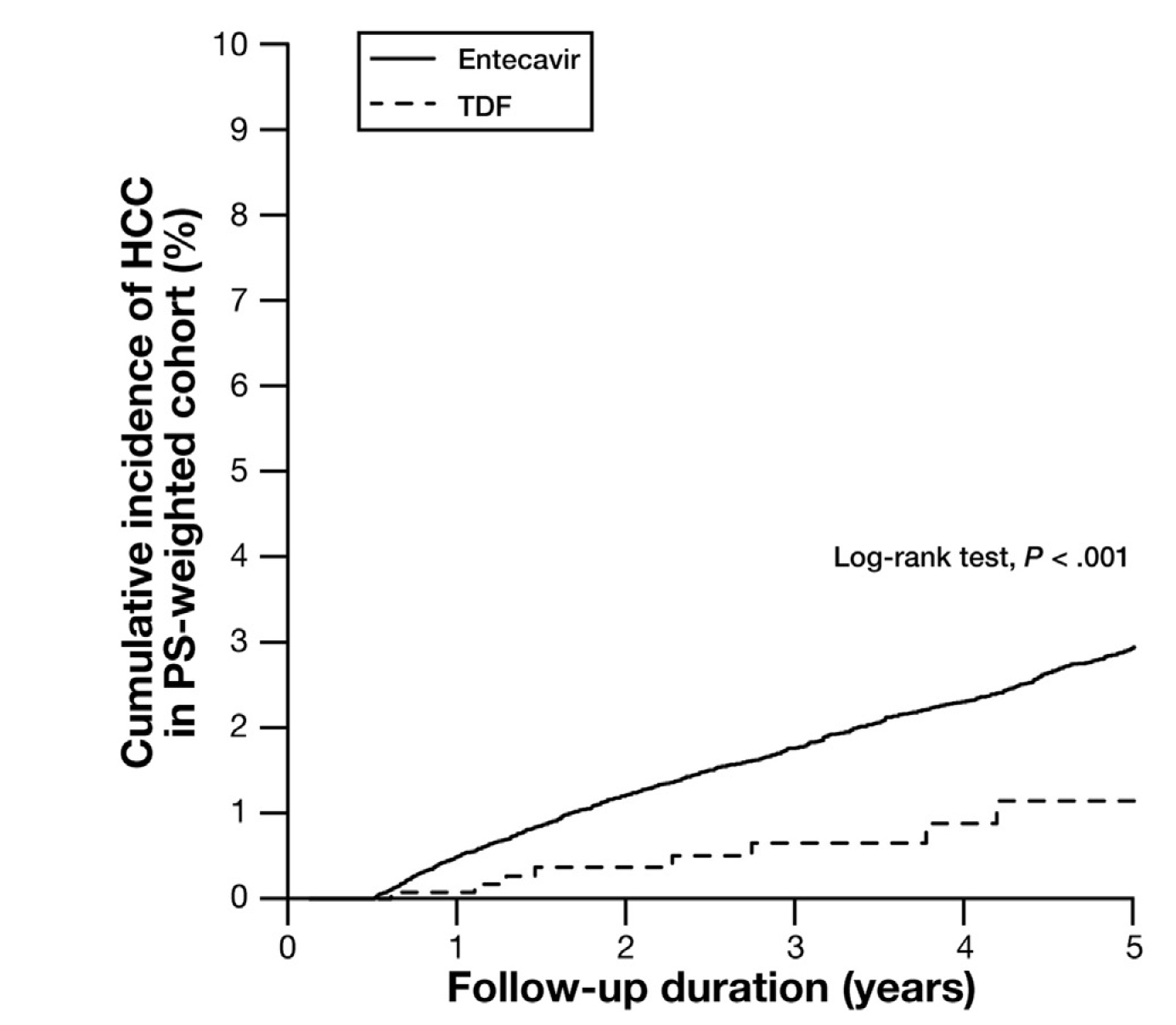

In controlling the risk of HCC in CHB patients, a retrospective study by Yip et al. (2020) involving the clinical data of 29,350 CHB patients who received treatment with ETV or TDF for at least 6 months demonstrated that TDF was associated with a lower risk of HCC than ETV, over a median follow-up time of 3.6 years (Figure 3)20. Although published meta-analyses on the efficacy of TDF and ETV in HCC were inconsistent, Prof. Wong summarised that the majority of the reports favoured TDF.

Figure 3. Cumulative incidence of HCC in CHB patients treated with TDF and ETV20

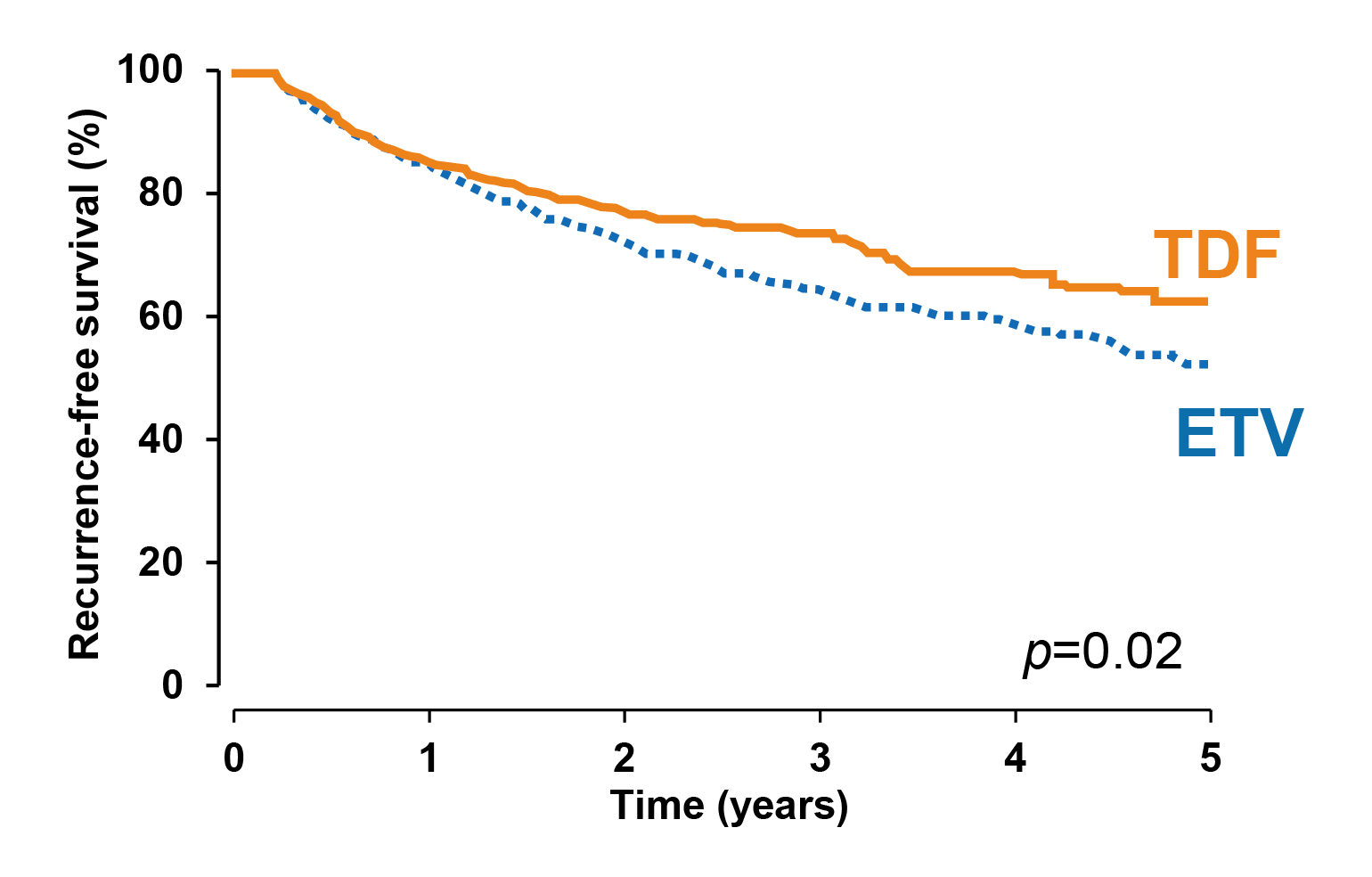

Apart from reducing the risk of HCC, Choi et al. (2021) compared HCC recurrence and survival of patients treated with TDF or ETV after surgical resection for HBV–related HCC. The results indicated that TDF treatment (n=882) was associated with significantly higher recurrence-free (p=0.02, Figure 4) and overall survival (OS, p=0.03) rates by propensity score (PS)–matched analysis versus ETV (n=813)21.

While TDF effectively suppresses HBV, Prof. Wong highlighted that TAF provides better long-term safety than TDF without compromising efficacy. According to the phase III 108/110 studies, ≥94% of patients on TAF and ≥91% switched from TDF to TAF maintained HBV suppression after 8-year follow-up22. Essentially, the 8-year follow-up further demonstrated that switching from TDF to TAF reversed the TDF-induced renal impairment and bone loss16.

Figure 4. Recurrence-free survival achieved with TDF and ETV21

In addition to HBV suppression, a recent analysis of 97 CHB patients switched from a prior nucleotide/nucleoside analogue (NA) to TAF by Sripongpun et al. (2022) revealed that switching to TAF resulted in a significant alanine aminotransferase (ALT) reduction, regardless of DM and BMI status23. Interestingly, Choi et al. (2020) reported that earlier ALT normalisation was independently associated with proportionally lower HCC risk24. “Given that TAF is effective in normalising ALT, the results supported the improved prognosis in CHB patients achieved by TAF,” Prof. Wong noted.

In considering the potential impact of CHB therapeutics on kidney function, Prof. Wong recommended that, for CHB patients with advancing age and comorbidities, it is crucial to choose a therapeutic with the lowest risk for nephrotoxicity. TAF is currently the therapeutic with more evidence support in this regard.

Given the increased bone fracture risk upon long-term TDF treatment, TAF was associated with a significantly lower fracture risk than TDF. For instance, a recent national-wide study by Kim et al. (2023) reported that, among 32,582 CHB patients in Korea, the incidence of osteoporotic fractures was 0.78 and 0.49 per 100 person-years in the TDF and TAF groups, respectively (HR: 0.68, p=0.001, Figure 5)25.

Figure 5. Overall fracture incidence in Korean CHB patient cohort25

Accordingly, Ogawa et al. (2024) demonstrated that the viral suppression rate increased significantly from 95.2% to 98.8% in 270 CHB patients 24 months after the switch from TDF to TAF (p=0.014). The mean spine T-score improved significantly from -1.43±1.36 to -1.17±1.38 (p<0.0001), while there was no significant change in mean eGFR (p=0.13) between the switch and 24 months later26.

Based on the clinical findings, Prof. Wong summarised that TAF effectively reduces the risk of adverse liver complications, including HCC, and can improve the outcomes in kidney and bone in CHB patients with comorbidities.

To illustrate the clinical challenges of comorbidities in managing CHB patients, Dr. Lai shared the cases of 2 patients. The first patient was a female aged 79 who had been diagnosed with CHB in the 1990s. She was treated with ETV since 2012 and good viral suppression was achieved. Besides, the patient was diagnosed with DM in 2001. Her glycaemic level was well-controlled (HbA1c: 6.1-6.7%) with metformin. Nonetheless, progressive CKD was diagnosed later with eGFR decreased from 77 to 63, and eventually 51 mL/min/1.73m2. Furthermore, a borderline ALT of 49-63 U/L with co-existing fatty liver was found. A subsequent dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan revealed the occurrence of osteopenia (T-score: -1.8 [hip], -1.6 [spine]).

In considering the declined kidney function and osteopenia of the patient, Dr. Lai switched the ETV treatment to TAF in late 2019. After 1 year of TAF treatment, improvements in kidney function and bone quality were observed. The eGFR progressively improved from 51 to 59 and 66 mL/min/1.73m2, whereas the T-score over the hip was increased from -1.8 to -1.5, and that over the spine was increased from -1.6 to -1.4.

The second patient was a male aged 63, with CHB diagnosed in the 2000s. Similar to the above case, the patient was prescribed ETV and achieved good viral suppression. However, this patient was diagnosed with DM in 2009, but the glycaemic control was suboptimal (HbA1c: 8.8%), though multiple oral treatments were tried. Hence, insulin has been treated since 2018. Remarkably, a 4.6 cm HCC was detected and surgically removed during the period. However, the biopsy test revealed advanced liver fibrosis and co-existing severe steatosis.

“With advancing age and sedentary lifestyle factors, metabolic syndromes and comorbidities in various organs, including liver, kidney, and bone, become more prevalent,” Dr. Lai highlighted. He commented that the 2 patients shared similarities, such as being older and having developed comorbidities. The female patient had developed DM, CKD, fatty liver, and osteopenia, while the male patient had DM, resected HCC, and advanced liver fibrosis with severe steatosis.

Dr. Lai noted that it is essential to consider which factors would increase the risk of liver complications, particularly HCC. While some risk factors, such as gender and age, are uncontrollable, factors including alcohol abuse, chronic co-infection with hepatitis viruses, and metabolic syndromes can be managed.

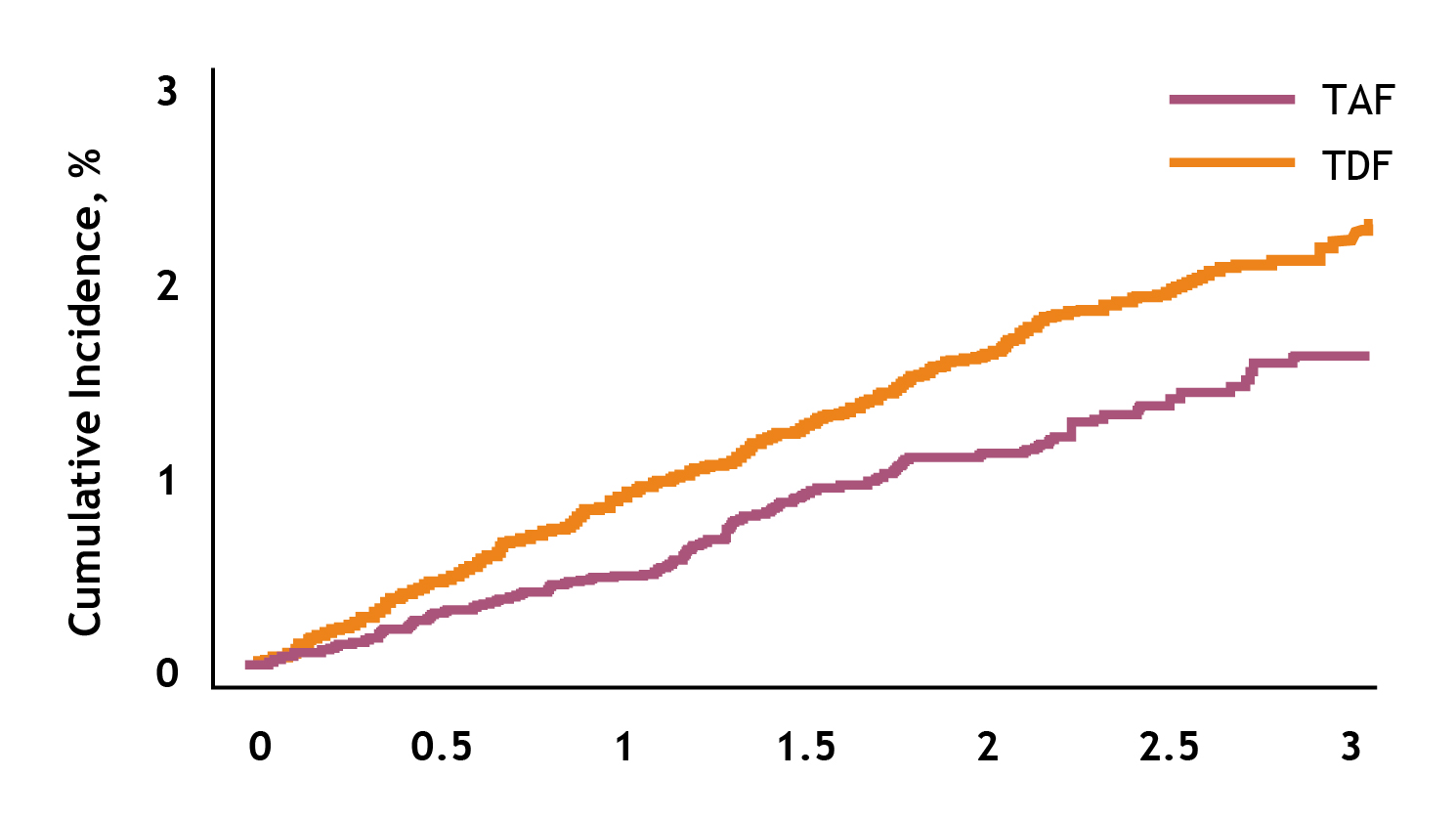

In controlling HCC risk with tenofovir, Dr. Lai opined that there is currently no evidence of TDF resistance in NA-naïve patients for up to 8 years. While TDF was shown to yield a significantly lower risk of developing HCC than ETV 20, a recent analysis by Lim et al. (2023) demonstrated that both TDF and TAF provided sustainable efficacy in controlling HCC risk, whereas a trend of lower cumulative incidence of HCC was observed with TAF (Figure 6)27.

Figure 6. Observed cumulative HCC incidence in patients who received TAF or TDF27

Besides controlling HCC risk, TAF was proven to have a better renal and bone safety profile than TDF. Switching from TDF to TAF would reverse TDF-associated renal impairment and bone loss16.

In selecting therapeutics for CHB patients, Dr. Lai noted that the safety profile of the medication is foremost considered, particularly the renal and bone impacts. TDF should be avoided in patients with renal impairment and risk of bone loss. On the other hand, ETV is not recommended in patients previously treated with lamivudine due to cross-resistance. Despite the adverse renal and bone impact, TDF is the preferred agent for pregnant women to prevent mother-to-child HBV transmission. More human data on the use of TAF during pregnancy is still needed.

Prof. Wong concluded that CHB patients are commonly complicated with comorbidities. Therefore, apart from focusing on the risk of adverse outcomes in the liver, it is vital to consider other complications, particularly a decline in kidney function and bone fracture risk. Based on the published clinical evidence, TAF is effective in suppressing HBV and reducing the risk of adverse kidney and bone outcomes. Given that clinical cases are far more complicated than those listed in the guidelines, Dr. Lai reminded us that treatment protocol should be individualised for each patient, whereas both the benefits and potential problems associated with the therapeutics have to be considered.

References

1. van der Spek et al. Eur J Intern Med 2023; 107: 86–92. 2. Wong et al. Hepatology 2020; 71: 444–55. 3. Wong et al. J Hepatol 2012; 56: 533–40. 4. Wong et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 883–93. 5. Wong et al. Gut 2009; 58: 111–7. 6. Yu et al. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2008; 26: 5576–82. 7. Paradis et al. Hepatology 2009; 49: 851–9. 8. Wong et al. Gut 2012; 61: 409–15. 9. Mao et al. Hepatology 2023; 77: 1735–45. 10. Mak et al. Hepatology 2023; 77: 606–18. 11. Yip et al. J Hepatol 2022; 77: S101–2. 12. Buti et al. J Hepatol 2014; 1 Supplement: S294–5. 13. Levey et al. Kidney Int 2005; 67: 2089–100. 14. Fabrizi et al. Ann Hepatol 2017; 16: 21–47. 15. Du et al. Medicine (United States) 2019; 98. DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000014262. 16. Lim et al. EASL Congress 2023; SAT-153. 17. Jung et al. Liver Int 2022; 42: 1017–26. 18. Sriprayoon et al. Hepatol Res 2017; 47: E161–8. 19. Yip et al. J Hepatol 2024; 80. DOI:10.1016/J.JHEP.2023.12.001. 20. Yip et al. Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 215-225.e6. 21. Choi et al. Hepatology 2021; 73: 661–73. 22. Buti et al. EASL Congress 2023; OS-067. 23. Sripongpun et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 20: 230–2. 24. Choi et al. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2020; 115: 406–14. 25. Kim et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2023; 58: 1185–93. 26. Ogawa et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2024; 59: 239–48. 27. Lim et al. JHEP Rep 2023; 5. DOI:10.1016/J.JHEPR.2023.100847.