Doctor at the National Health Services (NHS), United Kingdom (UK)

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is an aggressive lung cancer subtype with neuroendocrine differentiation diagnosed in more than 150,000 individuals globally each year. The 3-year survival rate for patients with extensive stage (ES) SCLC is around 6%, with addition of novel therapy, there is only a modest survival gain for a small subset of patients with ES-SCLC1. Furthermore, available therapies are limited for most patients with SCLC who relapse. Interestingly, the most widely used second-line agent, Topotecan has shown to have limited efficacy and an unfavourable safety profile and so far, no agent is specially designed for third-line treatment of relapsed SCLC. However, this is about to change with the bispecific T-cell engager molecule that binds to delta-like ligand 3 (DLL-3) and cluster of differentiation 3 (CD3) leading to tumour lysis1.

Lung cancer is the second most diagnosed cancer in the United States and is the leading cause of cancer death in both males and females, accounting for a quarter of all cancer deaths. It is histologically divided into 2 main types: SCLC and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)2. Interestingly, the SCLC comprises of 15% of lung cancer while NSCLC comprises of approximately 85%2. Notably, smoking is the leading cause of lung cancer, accounting for 85% of cases, followed by asbestos, radon, and other environmental exposures. Even though smoking has been associated with all types of lung cancer, it has the strongest associations with SCLC and squamous cell lung carcinoma2. Locally, lung cancer accounted for 15.9% of all cancer incidence and 26.4% of all cancer deaths in 2020. More concerning is the trend of continuous increase in crude incidence and a continuous decrease in age-standardised incidence over the past 2 decades, according to the Hong Kong Cancer Registry (HKCR)3.

But what is the reason for the rising cases in young individuals? Recent studies have highlighted an increasing trend of lung cancers seen in patients younger than the age of 40, who had no history of smoking. Some believe that the increasing trend may have been attributed by specific genetic mutations seen in some young individuals, as well as due to lifestyles choice such as vaping, smoking marijuana or inhaling other substance that may be considered as synergistic oncogens, predisposing individuals to lung cancers4. Moreover, these patients often have more advanced cancer and recent studies have advocated for gene mutation assessment as a mandatory tool to allow for a more individualised targeted therapy for achieving superior outcome5. The picture for young patients with SCLC is even gloomier as emerging studies have shown SCLC patients under the age of 50 represent a socioeconomically disadvantaged group with advanced disease at presentation. Furthermore, despite these individuals having fewer comorbidities and being offered the guideline concordant treatment, their survival rate is only marginally better than that of older adults in advanced stages6.

SCLC is characterised by aggressive disease progression and a tendency to metastasise to multiple organs and lymph nodes. Interestingly, 70-80% of patients with SCLC have ES-SCLC at the initial diagnosis and most of these are initially sensitive to chemotherapy, local or distant recurrence is inevitable, resulting in a poor prognosis7. So, what is so concerning regarding ES-SCLC? ES-SCLC is regarded as a refractory carcinoma associated with extremely rapid disease progression8 and after more than two decades without treatment progression, the addition of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1) axis blockade to platinum-based chemotherapy ushered a glimmering hope since it demonstrated a sustained overall survival (OS) benefit at first-line setting9. Nonetheless, despite thse benefit, the resistance emerges relatively quickly in virtually all patients, and this underscore the need of developing a more effective therapy in the clinical setting9.

What makes ES-SCLC so aggressive and difficult to treat? SCLC itself is very aggressive, characterised by high cellular proliferation and early metastatic spread. In fact, notch signaling is downregulated during neuroendocrine tumour growth and is inhibited by DLL3 expression. DLL3 expression is regulated by achaete-scute homolog 1 (ASCL1), a transcription factor that is required for proper development of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells and is an oncogenic driver in SCLC10. Furthermore, DLL3 expression has shown to promote SCLC migration and invasion in preclinical models through mechanisms that involves control of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition protein snail10. Therefore, DLL3 inhibition may be explored as a potential therapeutic target for SCLC, and ES-SCLC treatment.

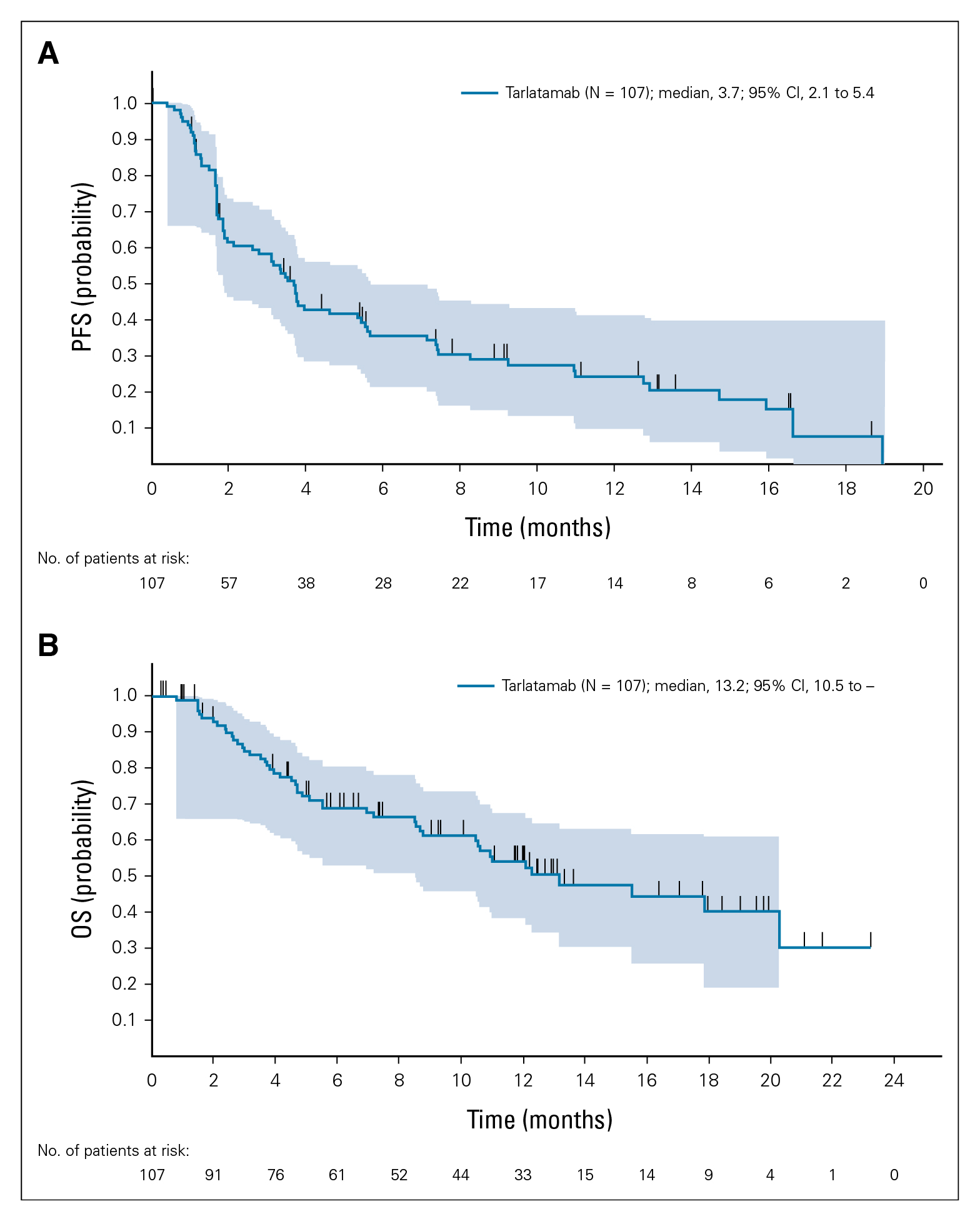

Recently, the emergency of bispecific T-cell engager immunotherapy targeting DLL-3 has showed some promising results in early phases of clinical trials in patients with previously treated SCLC, and more recently, Tarlatamab, which is the first-in-class drug approved for recurrent SCLC have received an Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval1. DeLLphi-300 was a phase 1 study that evaluated the safety and OS of patients with relapsed/refractory SCLC1. 107 patients included in the study received tarlatamab in dose exploration (0.003 to 100 mg; n=73) and expansion (100 mg; n=34). Median prior line anticancer therapy was 2 and 49.5% received anti-PD1 therapy. Remarkably, the median progression-free survival (mPFS) and OS were 3.7 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 41.5-61.2) and 13.2 months (95% CI: 10.5 to not reached), respectively. The conclusion reached from the early phase 1 trial suggested that patients with heavily pretreated SCLC showed durable response to tarlatamab treatment (Figure 1)1.

Figure 1. efficacy of tarlatamab in patients with SCC. (A) Kaplan-Meier curve of PFS for patients whose data cutoff date is at least 9 weeks after the first dose date (n=107). (B) Kaplan-Meier curve of OS for patients whose data cutoff data is at least 9 weeks after the first dose date (n=107)1. OS= overall survival; PFS= progression-free survival; SCLC= small-cell lung cancer.

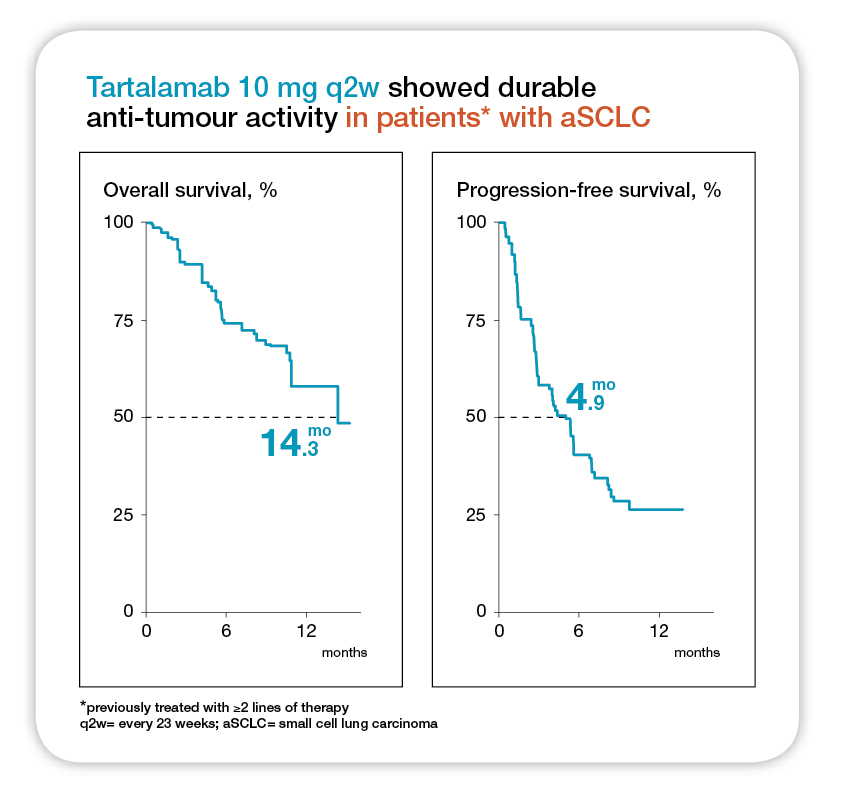

Similar, the DeLLphi-301 was a phase 2 trial that evaluated the anti-tumour activity and safety of tarlatamab in 220 patients previously treated for SCLC (received 2 lines of treatment previously)11. These patients received tarlatamab intravenously every 2 weeks at a dose of 10 mg or 100 mg and the primary end point was objective response (complete or partial response)11. The median follow-up was 10.6 months in the 10 mg group and 10.3 months in the 100 mg group. Interestingly, an objective response occurred in 40% (97.5% CI: 22-44) of those in 100 mg group. The mPFS was 4.9 months (95% CI: 2.9-6.7) in the 10 mg group and 3.9 months (95% CI: 2.6-4.4) in the 100 mg group (Figure 2)11. Remarkably, the estimates of OS at 9 months were 68% and 66% the two groups, respectively. The study concluded that tarlatamab administered at 10 mg dose every 2 weeks, showed anti-tumour activity with durable objective response and promising survival outcomes in patients with previously treated SCLC without any new safety signal concerns11.

Figure 2. Median follow-up was 10.6 months for tarlatamab 10 mg and 10.3 months for tarlatamab 100 mg. NE= not estimable; OS= overall survival; PFS= progression-free survival11.

Currently, the ongoing phase 3 DeLLphi-304 study will compare the efficacy and safety of tarlatamab (10 mg every 2 weeks) with standard-of-care chemotherapy in approximately 700 patients with relapsed SCLC after platinum-based first-line chemotherapy12. It is no doubt that the early results of tarlatamab are promising and represent a significant step forward towards the already limited treatment of advanced SCLC, particularly ES-SCLC. In conclusion, the one-size-fits-all paradigm is no long a feasible approach for both SCLS and ES-SCLC, instead a precision-based and personalised treatment may offer patients with a better survival chance and may one day change the SCLC management paradigm.

References

1. Paz-Ares L, et al. J Clin Oncol 2023; 41(16): 2893-903. 2. Basumallik N, et al. StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2024. 3. Au PCM, et al. The Lancet Regional Health - Western Pacific 2024; 45: 101030. 4. Shehata SA, et al. Cancers (Basel) 2023; 15(18). 5. Liu B, et al. J Cancer 2019; 10(15): 3553-9. 6. Lee MH, et al. J Thorac Dis 2022; 14(8): 2880-93. 7. Saida Y, et al. Onco Targets Ther 2023; 16: 657-71. 8. Yu Y, et al. International Journal of Cancer 2023; 152(11): 2243-56. 9. Zugazagoitia J, et al. J Clin Oncol 2022; 40(6): 671-80. 10. Owen DH, et al. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2019; 12(1): 61. 11. Ahn M-J, et al. New England Journal of Medicine 2023; 389(22): 2063-75. 12. Paz-Ares LG, et al. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2023; 41(16_suppl): TPS8611-TPS.