Clinician in Haematology and Haematological Oncology

The Challenging Nature of Hodgkin's Lymphoma

Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) is one of the most common cancers in young adolescents and young adults1 with over 50% of new HL cases recorded in 2021 among those under the age of 44 in Hong Kong2. Notably, the majority of patients with HL present with supradiaphragmatic lymphadenopathy at diagnosis and approximately one-third percent with systemic symptoms that include fever, night sweats and weight loss3. Considering fever, night sweats and weight loss are symptoms seen not exclusively in HL, it can often be challenging to distinguish between HL and other systemic diseases such as tuberculosis (TB); thus, patients can be misdiagnosed4. Furthermore, once HL is diagnosed, despite the treatment being very effective, patients are often plagued by significant short- and long-term side effects such as infections, infertility, organ failure and secondary malignancies5. Therefore, to understand the clinical issues related to HL, particularly at an advanced stage, we have invited Dr. Sin Yuen-Ting, a clinician in Haematology and Haematological Oncology to share her expertise in this area and to discuss further the management of this intricate disease through a clinical case-sharing.

Hodgkin's Lymphoma at a Glance

HL is a B-cell-originated malignancy of the immune system and one of the most frequent lymphomas seen in the Western world with an annual incidence of around three cases per 100,000 persons6. Interestingly, it is one of the most prevailing malignancies in young adults with a second peak reported in older adults and despite a high cure rate, around 20-35% of patients relapse, and approximately half of them eventually die of the disease or treatment-related late toxicities and secondary malignancies6. HL is composed of classical HL (cHL) and nodular lymphocyte-predominant HL7. In addition, Hodgkin (H) and Reed-Sternberg (RS) cells are often seen in cHL, representing the small mononucleated and large mono- or multinucleated subtypes collectively known as Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells6. Although there are no clearly defined risk factors for the development of HL, and the precise cause of HL remains elusive, certain factors such as familial history of HL, viral exposure, and immune suppression may increase the risk of developing HL in susceptible individuals7.

Imperceptibly, patients with HL generally present with superficial asymptomatic lymphadenopathy, commonly in the cervical, supraclavicular, and mediastinal lymph nodes8. Moreover, the presence of mediastinal mass may potentiate pleural or pericardial effusion9 and these may manifest as reduced breath sounds elicited during auscultation on clinical examination10, as per Dr. Sin. Aside from these disease manifestations, some patients may also present with B-symptoms which include high fevers, profound weight loss, and drenching night sweats11. Remarkably, the B-symptoms are evident in only up to 30% of patients and are generally more common in stages III or IV of the disease11. Therefore, Dr. Sin emphasised that clinicians should look out for other extranodal manifestations of the disease such as hepatosplenomegaly. In addition, she also suggested that specific blood tests such as the liver and renal function tests, full blood count, and other inflammation markers may aid the diagnosis and prognostication of HL. Where a suspicion of HL is strong, lymph node biopsy is warranted12, followed by a positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) for staging purposes13.

Striking a Balance between Efficacy and Toxicity

Treatment of HL is largely dependent on the histological characteristics, the stage of the disease and the presence or absence of poor prognostic factors11. The primary goal of the treatment is to cure the disease and to control the short and long-term complications11. The traditional treatment for early-stage HL (stages I-IIA) includes a combined chemotherapy consisting of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) or extended-field radiotherapy14,15. Whereas for advanced-stage HL, a contemporary treatment approach is taken and the challenge is often to improve the outcomes by identifying both high-risk patients who may benefit from more intensive frontline therapy to reduce the risk of relapse as well as to lower-risk patients in whom a less intensive therapy is adequate16. Nevertheless, despite the high 5-year overall-survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) rates of patients with advanced-stage disease (85% and 62%, respectively)17, patients are still at risk of experiencing short-and long-term adverse treatment effects18. For instance, complications related to ABVD treatment includes neutropenia, pulmonary toxicity, and cardiotoxicity19,20. Aside from these, young HL patients are often concerned about the infertility burden and secondary malignancy related to the HL treatment21. Contrary to this, older adults with HL are prone to poor performance status with a higher prevalence to treatment-related toxicity due to the pre-existing medical comorbidities22, Dr. Sin commented. Thus, striking a balance between maximising the treatment efficacy and reducing toxicity remains the priority when selecting appropriate treatment for patients with HL5.

To demonstrate the treatment dilemma often faced by HL patients, a long-term multi-centred study on 4,919 HL patients evaluated the impact of treatment-related morbidity on long-term cause-specific mortality in HL patients23. Patients had a median follow-up of 20.2 years and study results highlighted that HL patients had a staggering 5.1-fold higher risk of death due to causes other than HL. Furthermore, both the low and high-doses of anthracycline-containing chemotherapies were associated with an increased risk of mortality secondary to infectious diseases at both low-dose (hazard ratio [HR]= 2.67, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.19 to 5.98) or a high-dose (HR= 2.35, 95% CI = 1.12 to 4.94] 23. The study concluded that HL treatment may substantially reduce the life expectancy of cured HL patients and increased mortality related to AEs of HL treatment may persist for at least 40 years23. The authors also explained the chemotherapy-related increased risk of mortality may be attributed by the pulmonary toxicity associated with bleomycin which is co-prescribed with anthracycline23. On this note, Dr. Sin explained that since bleomycin, one of the chemotherapy agents used in HL treatment, is pulmonary toxic, and thus should be avoided in patients with chronic lung diseases24. Therefore, to overcome these shortfalls of traditional HL treatment, the brentuximab vedotin, doxorubicin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (BV+AVD) regimen has increasingly been used in advanced stages of HL25.

A Shift in Treatment Landscape of Hodgkin's Lymphoma

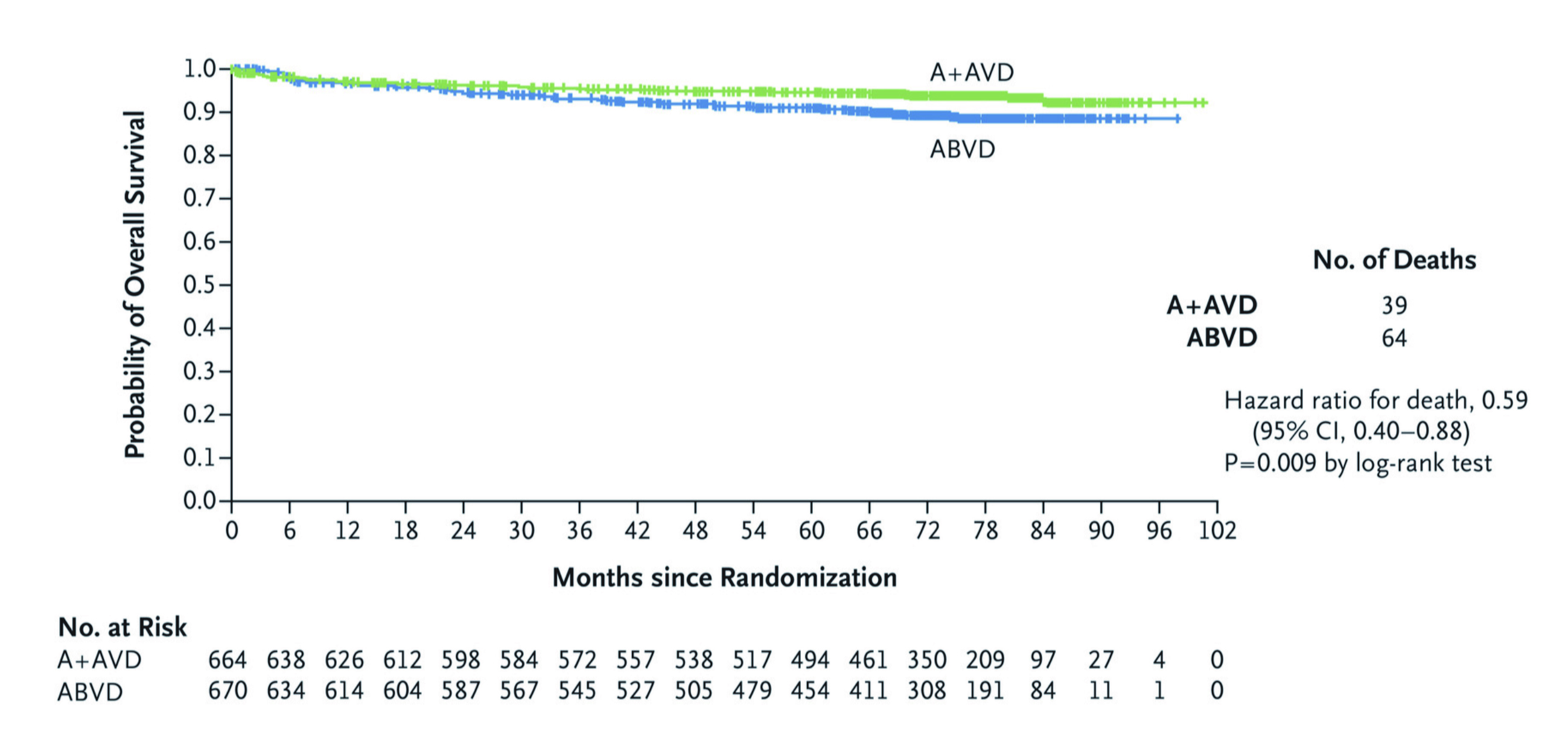

BV is an antibody-conjugated drug that targets the CD30 membrane receptors, which are highly expressed on the RS cells of HL26. Although BV was initially approved for use in the relapsed or refractory setting, its high efficacy and favourable toxicity profile led further studies evaluating its use as first-line, and second-line therapy in patients with HL27. To evaluate the long-term efficacy of BV+AVD chemotherapy with traditional ABVD treatment in patients with untreated stage III or IV classical HL, the ECHELON-1 study which was an open-label, multicentred, randomised phase 3 trial that included a total of 1,334 patients randomly assigned to receive either BV+AVD (664 patients) or ABVD (670 patients) treatment (1:1 ratio) with a median follow-up period of 73 months was conducted28. The primary endpoint was the modified PFS (defined as the time to progression, death, or noncomplete response and use of subsequent anticancer therapy according to the review by an independent committee) and the key secondary end point was overall survival (OS)29. The results showed that the rate of the primary end point of independently determined modified PFS in the BV+AVD group was significantly higher compared to the ABVD group, with a 2-year modified PFS rate of 82.1% (95% CI: 78.7-85.0) and 77.2% (95% CI: 73.7-80.4), respectively29. The efficacy persisted during 6 years follow-up with an estimated OS being 93.9% (95% CI: 91.6-95.5) in the BV+AVD group and 89.4% (95% CI: 86.6-95.5) in the ABVD group (Figure 1)28.

Figure 1. Overall survival comparing traditional ABVD therapy and BV+AVD therapy (Intention-to-treat population)28. ABVD= doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; BV+AVD= brentuximab vedotin plus doxorubicin, vinblastine and dacarbazine; CI=confidence interval.

Remarkably, the 6-year modified PFS estimates assessed by investigators were 82.3% in the BV+AVD group, which was higher than the ABVD group at 74.5% (hazard ratio for disease progression or death, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.53 to 0.86) (Figure 2)28.

Figure 2. Modified progression-free survival as assessed by investigator comparing traditional ABVD therapy and BV+AVD therapy (Intention-to-Treat population)28. ABVD= doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; BV+AVD= brentuximab vedotin plus doxorubicin, vinblastine and dacarbazine; CI= confidence interval.

Astonishingly, fewer patients in the BV+AVD group received subsequent therapy and the risk of death was significantly lower by 41% compared to that in the ABVD group28. Patients from both groups experienced common adverse events (≥30%) which included neutropenia, constipation, vomiting and fatique29. Yet, fewer second cancers (3.5% in BV+AVD group and 4.9% in ABVD group) and a higher number of pregnancies were reported in the BV+AVD group, further substantiating its effectiveness in extending the survival among HL patients without compromising safety28.

Real-World Clinical Application BV+AVD Therapy

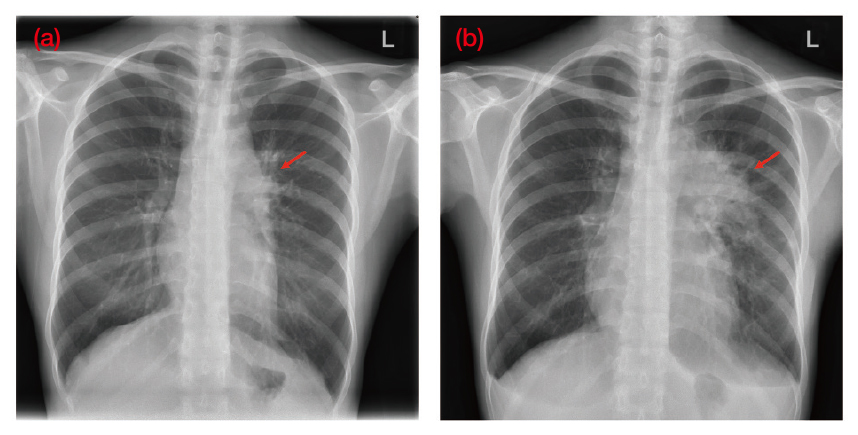

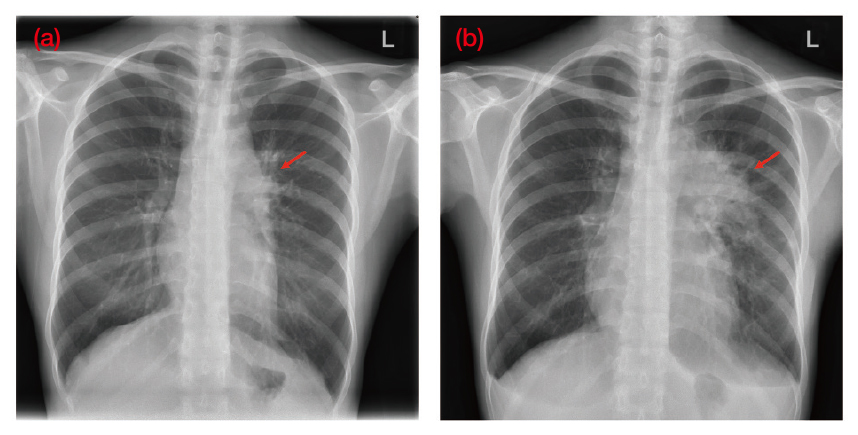

The treatment of HL has evolved considerably over the last 40 years30 and to illustrate the clinical performance of the BV+AVD chemotherapy regimen in advanced HL, Dr. Sin shared a case of a 28-year-old female who initially presented with chronic cough and dyspnea at the general outpatient clinic (GOPC). Furthermore, she was a non-smoker with no past medical or family history of cancers. Dr. Sin explained that the patient was initially treated for an upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) and despite this her symptoms did not improve. Hence, she reattended the GOPC and subsequently her treatment was escalated to an anti-asthmatic treatment, however, her symptoms persisted. Then in February 2022, patient attended the accident and emergency (A&E) and was promptly referred to the medical team for further assessment. Dr. Sin explained that it was during this admission a left-sided hilar lung mass was seen on her erect chest x-ray (Figure 3a).

Figure 3. An erect chest x-ray of the patient (a) taken during onset of symptoms at first medical consultation in early February 2022 and (b) taken prior to the commencement of chemotherapy in April 2022. Red arrows indicate (i) early signs of left hilar changes, (ii) prominent left hilar and mediastinal masses (Image provided by Dr. Sin)

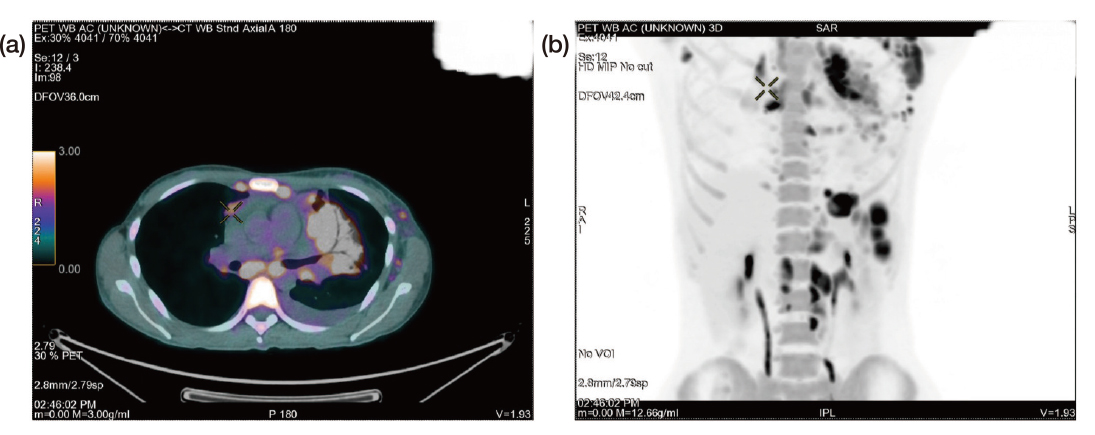

On physical examination, a significant lymphadenopathy was noted, particularly in the supraclavicular and axillary areas. Moreover, the clinical history revealed unintentional weight loss with constitutional symptoms that raised suspicion of cancer, particularly lymphoma. Consequently, patient underwent a PET-CT, which revealed pleural nodules, in addition to significant supraclavicular, mediastinal, and axillary lymph nodes pathology. As a result, an axillary lymph node biopsy was scheduled, however was delayed since the patient acquired the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection, Dr. Sin clarified. Upon her recovery from COVID-19, she finally underwent the axillary lymph node biopsy towards the end of March 2022 and was eventually diagnosed with stage IV classical HL with metastases involving both the lungs and the gastrointestinal tract confirmed by the PET-CT (Figure 4).

Figure 4. PET-CT images of the patient after diagnosis of stage IV Hodgkin¡¦s lymphoma (a) axial view and (b) anterior view (Image provided by Dr. Sin)

After diagnosis, patient was started on 6-cycled BV+AVD treatment in April 2022 and prior to commencing the first chemotherapy session, a further chest x-ray was taken which revealed a noticeably larger lung mass indicative of rapid disease progression, according to Dr. Sin (Figure 3b).

Figure 3. An erect chest x-ray of the patient (a) taken during onset of symptoms at first medical consultation in early February 2022 and (b) taken prior to the commencement of chemotherapy in April 2022. Red arrows indicate (i) early signs of left hilar changes, (ii) prominent left hilar and mediastinal masses (Image provided by Dr. Sin)

After receiving the 3rd cycle of BV+AVD, an interim PET-CT was requested by the patient that showed remarkable disease regression.

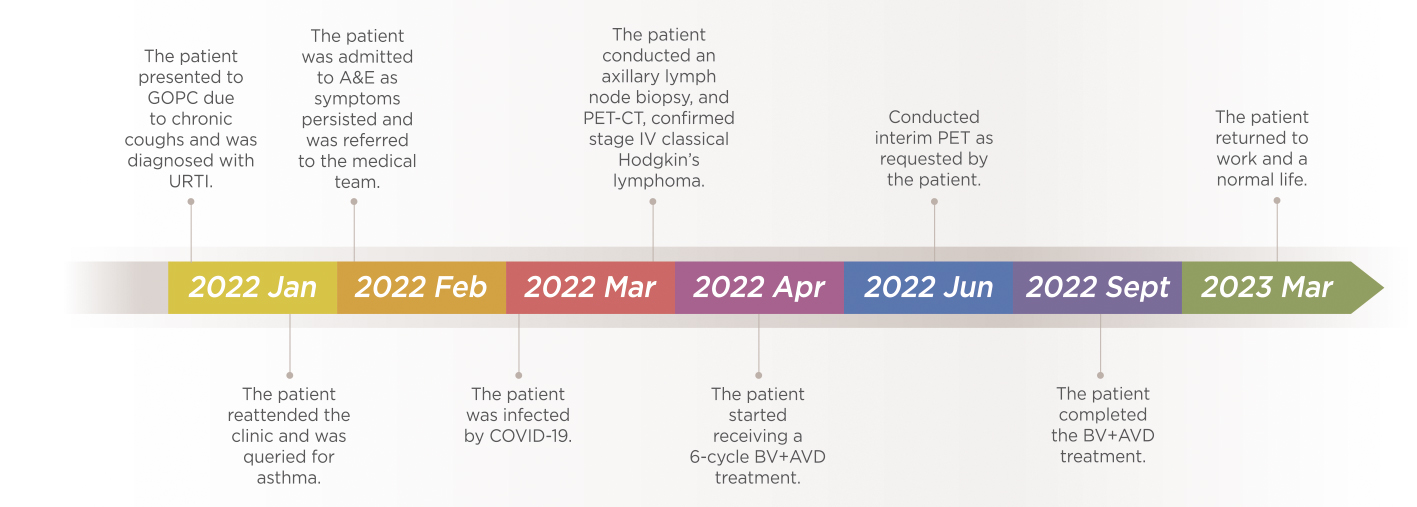

Dr. Sin elaborated that upon completion of 6 cycles of BV+AVD, the end-of-treatment PET-CT revealed a complete remission and after the treatment, patient resumed her clerical duties in March 2023 (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Timeline of the clinical case shared by Dr. Sin

When questioned whether the patient experienced any AEs during the 6-cycles of BV+AVD, Dr. Sin pointed out that the patient only experienced minor GI symptoms and overall, the treatment was promising with no significant complications. However, incidentally the patient was admitted to A&E during the 4th cycle of the BV+AVD treatment due to neutropenic fever which was treated with a course of antibiotics.

Consensus Driven Management of HL

Dr. Sin advocated the importance of being vigilant towards patients who exhibit non-specific symptoms of the disease and when in doubt, always conduct systemic imaging promptly. She further added that patient may not be aware of their symptoms and may not present in a timely manner. These observations reported by Dr. Sin has also been substantiated in a qualitative study by Howell et al. (2019) that evaluated the issues relating to the delay in lymphoma diagnosis. The study concluded that due to the complex characteristics of lymphoma, non-specific symptoms are often initially thought to be associated with various benign, self-limiting causes31. Moreover, some lymphomas are misdiagnosed as tuberculosis (TB) due to similarity of symptoms and this may prolong initiation of appropriate treatment, thereby, worsening the disease progression32. “Clinician should take a systematic approach to HL that is patient-centred and addresses patients¡¦ concerns,” as per Dr. Sin. She further elaborated that “patients at child-bearing age are often concerned regarding the fertility preservation, hence a referral to the fertility clinic for counselling may reassure their needs.” On a final note, regarding the HL treatment, Dr. Sin concluded that the BV+AVD regimen has a high therapeutic efficacy which is consistent with those reported in the clinical trials, and a good safety profile with manageable side effects.

References

1. Kahn et al. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2018; 65(7): e27033. 2. Authority HKH. Hong Kong Cancer Statistics. 2024. Available from: https://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/allagesresult.asp. 3. Ansell SM. Am. J. Hematol. 2020; 95(8): 978-89. 4. Roumi et al. Clin Case Rep 2023; 11(5): e7290. 5. Follows et al. Cancers (Basel) 2022; 14(21). 6. Gopas et al. Cell Death Dis 2016; 7(11): e2457-e. 7. Ansell SM. Am. J. Hematol. 2022; 97(11): 1478-88. 8. Göknar et al. Hematol Rep 2015; 7(2): 5644. 9. Akata K et al. Thorac Cancer. Published online December 30, 2023. doi:10.1111/1759-7714.15197 10. Krishna R et al. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28846252/ 11. Kaseb H et al. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29763144/ 12. Lewis WD et al. Am Fam Physician 2020; 101(1): 34-41. 13. Ghesquières H. Rev Prat 2023; 73(6): 617-20. 14. Ansell SM. Mayo Clin Proc 2015; 90(11): 1574-83. 15. Gobbi PG et al. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2013; 85(2): 216-37. 16. Spinner MA et al. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2018; 2018(1): 200-6. 17. Suwanban T et al. Cancer Rep (Hoboken) 2023; 6(8): e1839. 18. Laddaga FE et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma and Leuk2020; 20(8): e506-e12. 19. Law MF et al. Arch Med Sci 2014; 10(3): 498-504. 20. Vakkalanka B et al. Adv Hematol 2011; 2011: 656013. 21. Machet A et al. Blood Adv 2023; 7(15): 3978-83. 22. Evens AM et al. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2019; 2019(1): 233-42. 23. de Vries S et al. J Natl Cancer Inst 2021; 113(6): 760-9. 24. Patil N et al. J Clin Diagn Res 2016; 10(4): Fr01-3. 25. Bowers JT et al. Blood Adv 2023; 7(21): 6630-8. 26. Alperovich A et al. Cancer J 2016; 22(1): 23-6. 27. Moskowitz AJ. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2018; 2018(1): 207-12. 28. Ansell SM et al. N Engl J Med 2022; 387(4): 310-20. 29. Connors JM et al. N Engl J Med 2017; 378(4): 331-44. 30. Vellemans H et al. Cancers (Basel) 2021; 13(15). 31. Howell DA et al. Br J Gen Pract 2019; 69(679): e134-e45. 32. Banerjee A et al. J Med Case Rep 2021; 15(1): 351.