Patients with acute or critical illnesses are susceptible to developing malnutrition, either as a direct result of the disease or due to treatment adverse effects (ADs)1. While disease-related malnutrition (DRM) is associated with various adverse outcomes, such as physical disability, hospitalisation, increased risk of all-cause mortality, and other comorbidities2, appropriate nutrition is likely to reduce the disease severity, and provide favourable patient outcomes3. Notably, parenteral nutrition (PN) has been widely used in both paediatric and adult patients whenever oral or enteral nutrition (EN) is not possible, insufficient, or contraindicated. However, PN has been reported to increase the risk of complications including infection, hyperglycaemia, and electrolyte disturbances4. Thus, a proper prescription of PN requires appropriate patient selection, careful monitoring, and the expertise of an interdisciplinary team. The objective of this article is to discuss the controversy related to the PN reported in the literature, to review the therapeutic performance of PN, and explore ways to optimise PN treatment.

Underutilisation and Delayed Prescription of Nutrition Therapy

PN is required when oral feeding or EN is not possible for a period, not only to maintain the desirable body composition and the potential for physical and mental activity but also to enable therapeutic measures5. The treatment entails the administration of a solution of chemically defined elemental nutrients directly into the bloodstream instead of uptake in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract6. Of note, complete nutritional needs may be provided through total parenteral nutrition or supplemented, where the formula is customised to meet the unique and individual nutritional needs of each patient which may include carbohydrates, amino acids, lipids, electrolytes and/or micronutrients7.

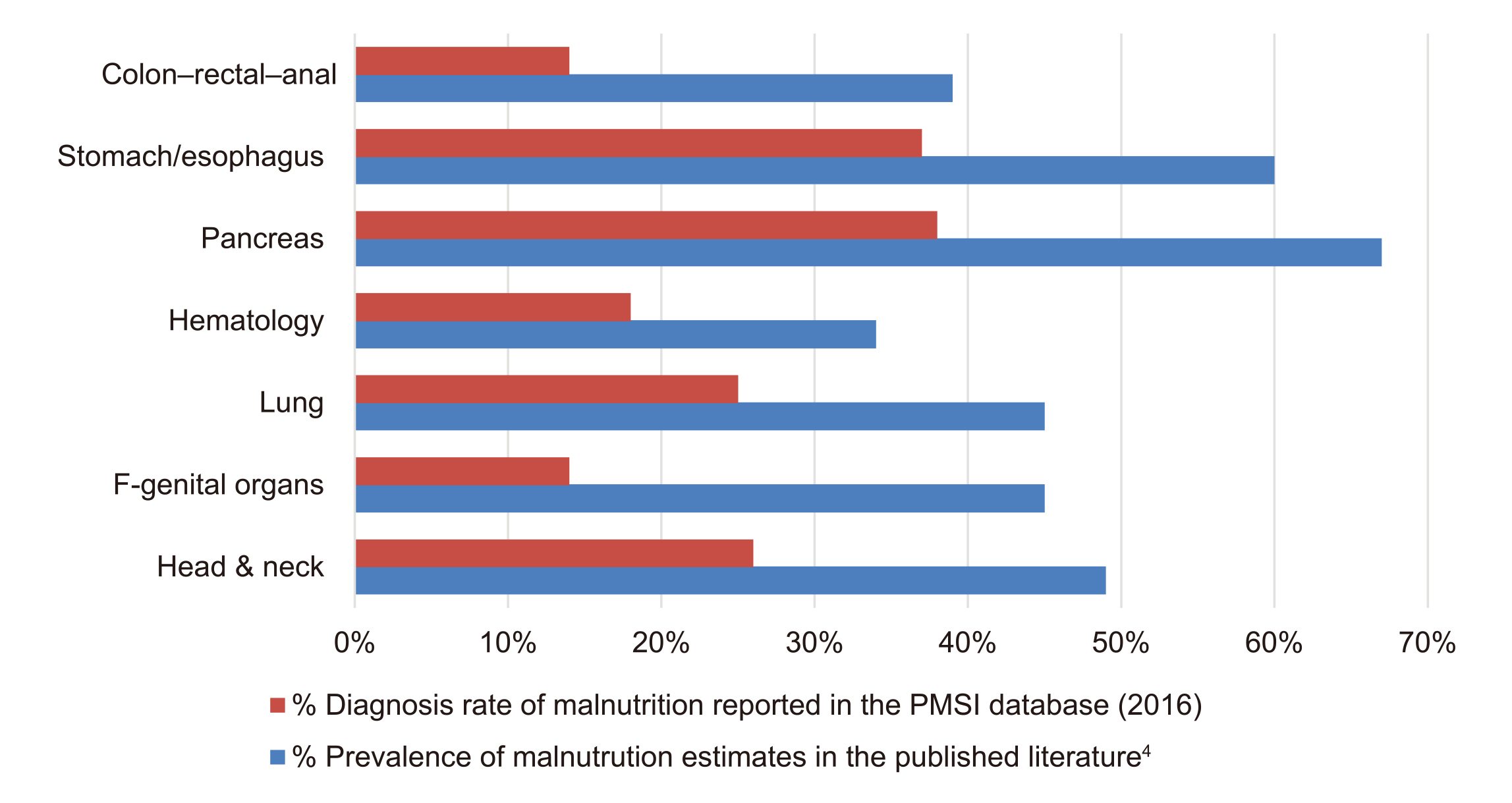

Although nutrition therapy can be a life-saving intervention for patients with critical nutritional risk, the therapy is often underutilised in the clinical practice. For instance, a retrospective analysis on data from 3 administrative healthcare databases from France (n=570,727), Germany (n=4,642), and Italy (n=58,468) on the use of clinical nutrition in the real-world setting by Caccialanza et al. (2020) revealed that, according to the data obtained between 2013 and 2016 from the French database, malnutrition diagnosis at first hospitalisation occurred in 10% of patients, 13% were subsequently diagnosed after the first hospitalisation, and the remaining 77% had no malnutrition diagnosis1. Remarkably, the results obtained from the study also highlighted that about one-third of the 1.2 million cancer patients in the French database 2016 reported with a diagnosis of malnutrition, which was substantially lower than the published prevalence estimates (Figure 1)1.

Figure 1. Comparison between prevalence estimates of malnutrition in French database and published literature1, PMSI: Program for the Medicalization of Information Systems

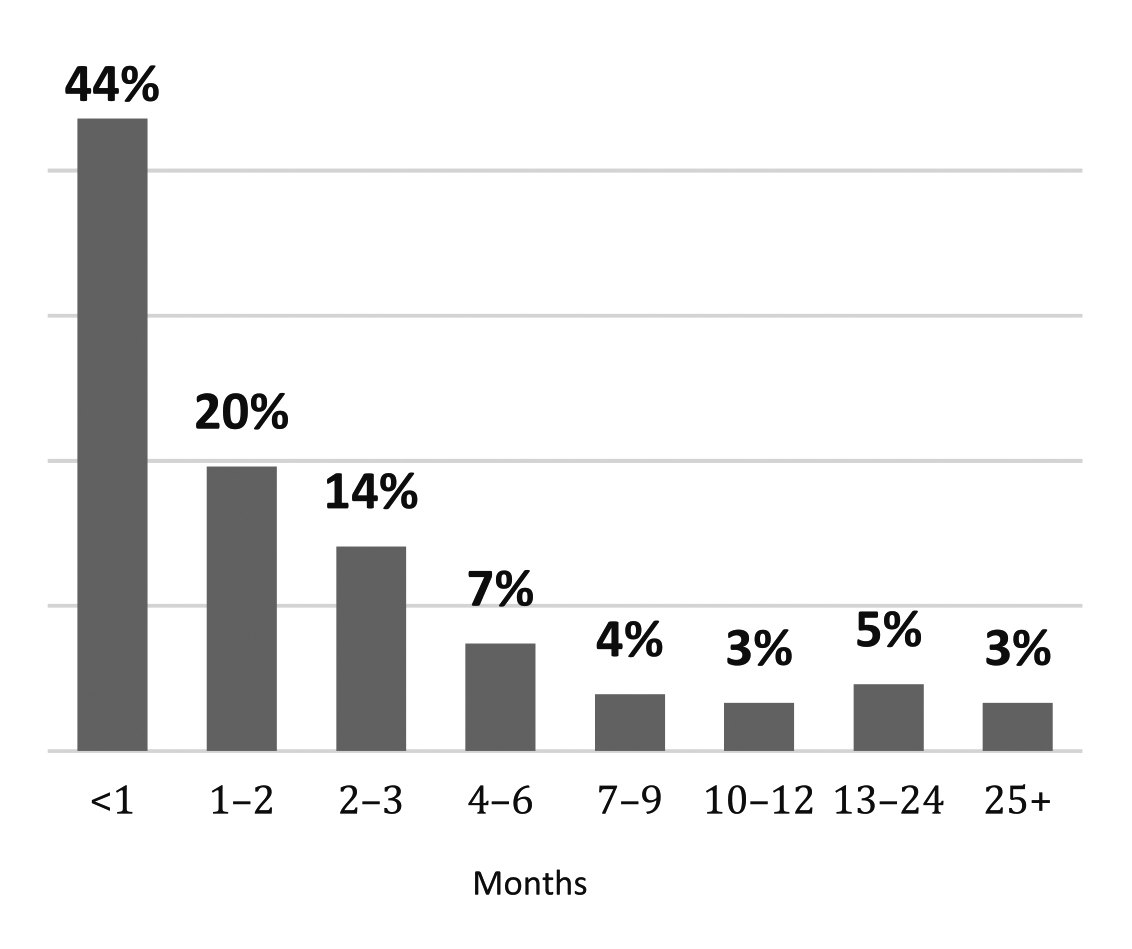

Besides, based on the analysis of the Italian database between 2009 and 2015, only 8.4% out of 69,000 patients with metastatic cancer had received appropriate clinical supplementary nutrition. However, a staggering 18% of the patients with metastatic cancer only received their first nutrition treatment after more than 1 year. Surprisingly, 44% of patients with metastatic cancer received clinical nutrition treatment only less than 1 month before death (Figure 2)1. Therefore, these results of the large-scale, multinational analyses suggest that there is a significant under-recognition of malnutrition and delayed initiation of appropriate nutrition therapy in real-world clinical practice.

Figure 2. Percentage of patients by month from the first clinical nutrition treatment to death1

PN - To Be or Not to Be?

The European Society of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) Guidelines on clinical nutrition in surgery advocate nutritional therapy for patients with malnutrition, at nutritional risk, or anticipated to be nil by mouth for more than 5 days. Additionally, nutritional therapy is indicated for patients in whom oral intake is anticipated to be inadequate for more than 7 days8. Nonetheless, routine use of PN is not recommended and all other feeding routes should be considered prior to initiating PN due to the risk of complications related to PN6. Of note, the complications of PN can be classified into 3 main categories, including metabolic complications, infectious complications, and non-infectious catheter-related complications.

Among the complications related to PN, hyperglycaemia is the most common. A former clinical study suggested that up to 63.3% of hospitalised patients that received PN developed hyperglycaemia secondary to prolong use of PN (p=0.03)9. Moreover, PN-associated hypertriglyceridemia occurs when the infusion rate of intravenous fat emulsion (IVFE) exceeds the capacity of plasma fat clearance, and this may also develop with glucose overfeeding. Remarkably, refeeding syndrome (RS) is a critical metabolic complication characterised by fluid complications and electrolyte imbalances occurring during the early stages of the nutritional therapy. In addition, PN also increases the risk of hepatobiliary complications, ranging from mild liver enzyme abnormalities to liver cirrhosis4.

Aside from metabolic complications, catheter-associated blood steam infection (CRBSI) is a common infectious complication related to the PN, leading to hospital readmissions, loss of venous access, and a decreased quality of life (QoL). Besides, PN-associated non-infectious catheter complications, such as catheter occlusions, malposition of the catheter tip, may also lead to adverse treatment outcomes4.

However, given the benefits and risks of PN, the optimal timing of initiating PN remains controversial. The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) guidelines recommended to initiate PN early when EN is not feasible or sufficient in patients who are at high-risk of developing malnutrition or are poorly nourished10.

The Crucial Role of Healthcare Professionals

When PN is appropriately prescribed, it can significantly improve the nutritional well-being of malnourished patients. A recent local study by Ting et al. (2021) including the records of 81 hospitalised patients demonstrated that patients received PN managed by the nutrition support team (NST, n=44), a multidisciplinary team of physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and dietitians, had a significantly higher energy (1,279±353 kcal vs 934±261 kcal) and protein intake (58±16g vs 43±12g) than that of the control group (n=37). Moreover, the percentage of achieved targeted energy (81±21%) and protein requirement (90±28%) was significantly higher in NST group compared to the control (64±21% and 75±23%, respectively). Essentially, 88.6% of patients in the NST group achieved adequate intake of micronutrients from PN, which was significantly higher than that seen in the control group (8.1%)11. These findings thus showed that PN provided by the NST is promising to ensure the nutrition well-being, in terms of energy and nutrient intake, of hospitalised malnourished patients.

Optimising PN Treatment – Right Patient, Right Contents, and the Right Way

The study by Ting above reflects that the outcomes of PN treatment are governed by various factors, particularly the support provided by healthcare professionals. One of the key considerations when prescribing PN is to determine the patient group in whom the treatment is indicated. According to the position statement for critical care nutrition endorsed by the Hong Kong Society of Critical Care Medicine (HKSCCM) and the Hong Kong Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (HKSPEN), nutrition screening of critically ill patients by the Nutrition Risk in the Critically Ill (NUTRIC) score is recommended within 48 hours of ICU admission. The assessment aims to estimate the patient’s nutrition risk in order to identify patients who require special attention and to determine the patient’s metabolic needs. Moreover, the position statement advocated that specific nutritional interventions may be required in patients with renal disease, liver disease, and acute pancreatitis, while a multi-disciplinary team, i.e. the NST, should be involved in nutrition therapy. Importantly, supplementary PN should be initiated if and only if EN is not tolerated despite all strategies3.

When PN is required, choosing the appropriate intravenous lipid emulsions (ILEs) is vital for providing adequate energy and macro/micro-nutrients, as well as preventing the risk of metabolic complications. Nowadays, ILEs with various contents are available. Interestingly, there is emerging evidence that showed the benefits of PN with fish oil (FO)-containing ILEs (FO-ILEs) on clinical outcomes. FO is a source of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), which are essential for normal growth and development, with several known anti-inflammatory mechanisms of action12.

A meta-analysis by Pradelli et al. (2023), which included 47 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), compared the effectiveness of different ILEs in improving clinical outcomes, in terms of infections, sepsis, ICU and length of hospital stay, and in-hospital mortality among hospitalised patients. The results confirmed that FO-ILEs yielded significant reductions in infection risk versus soybean oil (SO)-ILEs (odds ratio [OR]: 0.43), medium-chain triglyceride (MCT)/SO-ILEs (OR: 0.59), and olive oil (OO)-ILEs (OR: 0.56). The results also indicated that FO-ILEs showed a lower risk of sepsis when compared to other SO-ILEs (OR: 0.22). Essentially, substantial reduction in length of hospital stay was observed in FO-ILEs compared to SO-ILEs (mean difference [MD]: -2.31 days) and MCT/SO-ILEs (MD: -2.01 days)13. Thus, these findings suggested that PNs with omega-3 fatty acids may improve clinical outcomes of hospitalised patients.

Although appropriately prescribed nutrition therapy is undoubtedly a life-saving treatment for critically malnourished patients, however, the clinical opinions on the implications and practical issues related to the prescribed nutrition therapy remains inconsistent. Yet, it is generally accepted that personalised nutrition therapy is essential to the future of critical care. For instance, the position statement of HKSCCM and HKSPEN advocated that the exact composition and infusion rate in PN should be tailored to the nutritional and fluid needs of each individual patient by a multidisciplinary team of physicians, nutritionists, pharmacists, and nurses3. In summary, when prescribing nutrition therapy based on recommended nutrition screening protocol, selecting the appropriate nutrient composition, and the care provided by a NST are the key steps for optimising the health outcomes for malnourished patients.

References

1. Caccialanza R et al. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2020; 12. 2. Meyer F et al. Visc Med 2019; 35: 282–90. 3. Chang LL et al. Crit Care Shock 2021; 24: 153–71. 4. Berlana D. Nutrients 2022; 14. 5. Berger MM et al. Journal of intensive medicine 2022; 2: 22–8. 6. Corrigan M et al. Nutritional Care of the Patient with Gastrointestinal Disease 2015; 321–45. 7. Fetterplace K et al. Intern Med J 2020; 50: 403–11. 8. Weimann A et al. Clinical Nutrition 2021; 40: 4745–61. 9. Elizabeth PC et al. Human Nutrition & Metabolism 2020; 22: 200114. 10. McClave SA et al. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2016; 40: 159–211. 11. Ting HYT et al. Gut 2021; 70: A92–3. 12. Martin J et al. Diet and Nutrition in Critical Care 2015; : 1695–710. 13. Pradelli L et al. Clinical Nutrition 2023; 42: 590–9.