Editor-in-Chief, V·Pulse

The French paradox refers to the low incidence and mortality rates from ischaemic heart disease in France, though saturated fat intakes, serum cholesterol, blood pressure and prevalence of smoking are no lower there than elsewhere. While under-reporting may partially explain the phenomenon, numerous clinical findings and opinions advocate that the protection against ischaemic heart disease among the French is attributed to their high wine consumption1. The doctrine of health benefits of wines conflicts with the traditional beliefs about the harm of alcohol consumption. In this regard, this article aims to discuss the health impacts of wines by reviewing the chemistry of the beverage and highlighting notable clinical findings associated with wine consumption.

The key process in wine production is the conversion of sugars in grapes into alcohol through fermentation by the action of yeasts. Alcoholic fermentation is a 2-step reaction after the release of sugars from the ripened grapes. The first step involves the conversion of pyruvate to acetaldehyde by the action of pyruvate decarboxylase with thiamine pyrophosphate as the cofactor. The second step is the reduction of acetaldehyde to ethanol by reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) catalysed by alcohol dehydrogenase. Of note, most red wines and some white wines undergo secondary malolactic fermentation by the bacteria Oenococcus oeni. The bacteria convert the malic acid in the wine to lactic acid. This reaction gives the resulting wine a softer mouthfeel and generates diacetyl, which has a very buttery taste2.

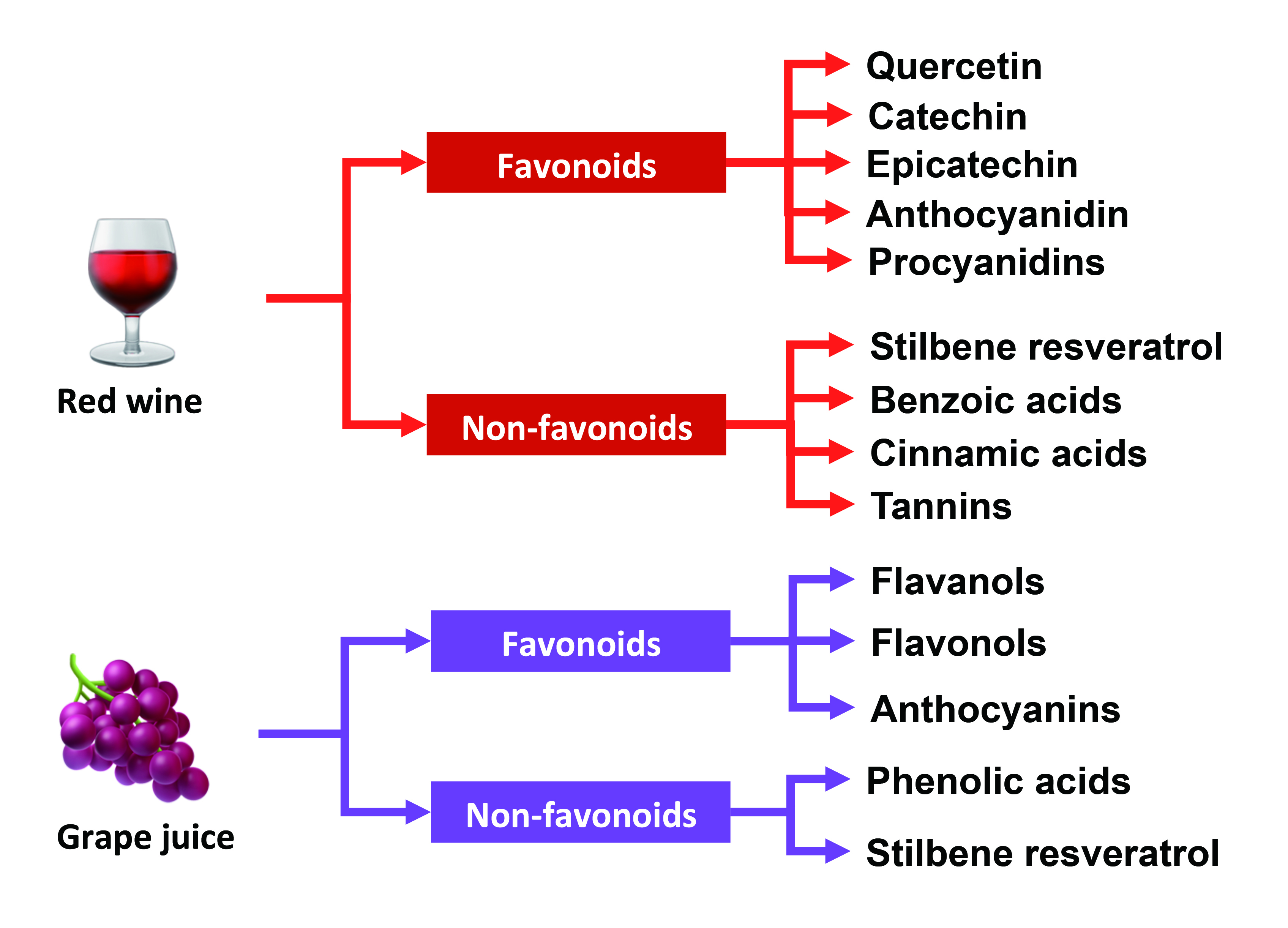

Grape juice is a non-fermented drink with characteristic colour, aroma, and flavour. Flavonoids, including flavonols, flavanols, anthocyanins, and other phenolic compounds, such as phenolic acids and stilbene resveratrol, are the main chemical components contributing to the health benefits of grape juice3. On the other hand, wine is a complex solution containing hundreds of chemical components, with water, ethanol, monosaccharides, acids, minerals, and phenols being the major constituents2. The main phenolic compounds of wine are flavonoids, non-flavonoids (such as stilbene resveratrol and hydroxybenzoic acids), and anthocyanins3. Essentially, the respective composition and levels of the chemical components in grape juice and wine are different. For instance, Copetti et al (2018) reported that the total phenolic content, concentrations of total monomeric anthocyanins and total flavonols in wine were significantly higher than those in grape juice. Also, the total antioxidant activity in vitro of wine was significantly higher compared with grape juice4. The respective phenolic compounds in red wine and grape juice are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Phenolic compounds found in red wine and grape juice3

Figure 1. Phenolic compounds found in red wine and grape juice3

The benefits of wine consumption on cardiovascular health have been widely investigated. Former studies attributed the cardiovascular outcomes mainly to the presence of various polyphenolic compounds in red wines. In particular, resveratrol is considered the most effective compound for preventing coronary heart disease (CHD) because of its antioxidant properties.

In a double-blinded, randomised control trial (RCT) involving 40 post-infarction Caucasian patients by Magyar et al (2012), patients who received daily treatment with resveratrol capsule for 3 months exhibited significant improvement in left ventricular diastolic function (p <0.01) and endothelial function measured by flow-mediated vasodilation (FMD, p <0.05) compared to the placebo group. A significant decrease in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels (p <0.05) was observed in the resveratrol-treated group. Moreover, resveratrol also prevented unfavourable hemorheological changes in terms of red blood cell deformability and platelet aggregation5.

Apart from resveratrol, many studies advocated the protective effect of flavonoids on cardiovascular diseases. For instance, the consumption of flavanol-rich foods has been reported to lower blood pressure in both healthy and at-risk populations, such as those with hypertension and impaired cardiovascular function6. Remarkably, Guerrero et al (2012) suggested that certain flavonoids possess an inhibitory effect on angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) activity, suggesting the role of the compounds in the regulation of arterial blood pressure7.

Besides, anthocyanins are a major chemical component in grape and wine, contributing to the cardioprotective potential8. Huang et al (2014) reported that malvidin-3-glucoside and malvidin-3-galactoside, the most common anthocyanins in red wine, provide anti-inflammatory effects in endothelial cells9. Notably, a cohort study of 98,469 participants by McCullough et al (2012) confirmed that anthocyanidins and proanthocyanidins are associated with a lower CHD risk10.

In addition to cardioprotective effects, wine consumption has been demonstrated to provide protective effects against cognitive decline. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Lucerón-Lucas-Torres et al (2022), which included 12 longitudinal studies of sample sizes ranging from 360 to 10,308 with a mean age of 70 years old in 9 countries, identified a possible protective effect of wine consumption on the development of cognitive decline (pooled relative risk [RR]: 0.72). The effect appeared independent of age, the percentage of women, and follow-up time. Nonetheless, the results did not suggest the population should increase wine consumption, whereas low-to-moderate wine consumption could be promoted to prevent or delay cognitive deterioration in the healthy population11.

Despite the health benefits of wines have been demonstrated in numerous studies, there is evidence of the adverse outcomes of alcohol intake. In light of the inconsistent findings, some researchers attempted to figure out a more comprehensive picture of the health impacts of wine consumption. Interestingly, a prospective study by Schutte et al (2020) evaluated the health risks associated with different types of alcoholic drinks. In the study, over 500,000 participants were recruited, and details of alcohol consumption were recorded weekly. The health outcomes of reported all-cause mortality, cardiovascular events, ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular events, and cancer were followed for a median of 7.02 years follow-up12.

After excluding non-drinkers, the results indicated that beer/cider and spirits intake were associated with an increased risk for all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.56 [beer/cider]; 1.47 [spirits], Figure 2a), cardiovascular events (HR: 1.25 [beer/cider]; 1.25 [spirits]), ischemic heart disease (HR: 1.12 [beer/cider]; 1.17 [spirits]), cerebrovascular disease (HR: 1.63 [beer/cider]; 1.59 [spirits]) and cancer (HR: 1.14 [beer/cider]; 1.14 [spirits]), while both champagne/white wine and red wine were associated with a decreased risk for ischemic heart disease (HR: 0.84 [champagne/white wine]; 0.88 [red wine], Figure 2b)12. Therefore, the findings showed that some alcoholic beverages, such as beer/cider and spirits, are indeed associated with an increased risk of adverse health outcomes, whereas wines showed opposite protective relationships with ischemic heart disease.

Figure 2. Hazard ratios for (a) all-cause mortality and (b) cardiovascular events12, Number of pints, glasses or measures were stratified by 1-7 (¡´), 8-14 (¡»),15-21 (¡¶), and >21 (¡½) per week.

Figure 2. Hazard ratios for (a) all-cause mortality and (b) cardiovascular events12, Number of pints, glasses or measures were stratified by 1-7 (¡´), 8-14 (¡»),15-21 (¡¶), and >21 (¡½) per week.

In addition to beverage type, drinking pattern, including frequency and consumption with food or not, has been shown to affect health outcomes. The prospective cohort study by Jani et al (2021) involving 309,123 participants in the UK Biobank indicated that, similar to the study of Schutte et al above, spirit drinking was associated with higher adjusted mortality (HR: 1.25), major cardiovascular events (MACE, HR: 1.31), cirrhosis (HR: 1.48) and accident/injuries (HR: 1.10) risk compared to red wine drinking, after adjusting for the average weekly alcohol consumption amounts. Moreover, beer/cider drinkers were also at a higher risk of mortality (HR: 1.18), MACE (HR: 1.16), cirrhosis (HR: 1.36) and accidents/injuries (HR: 1.11)13.

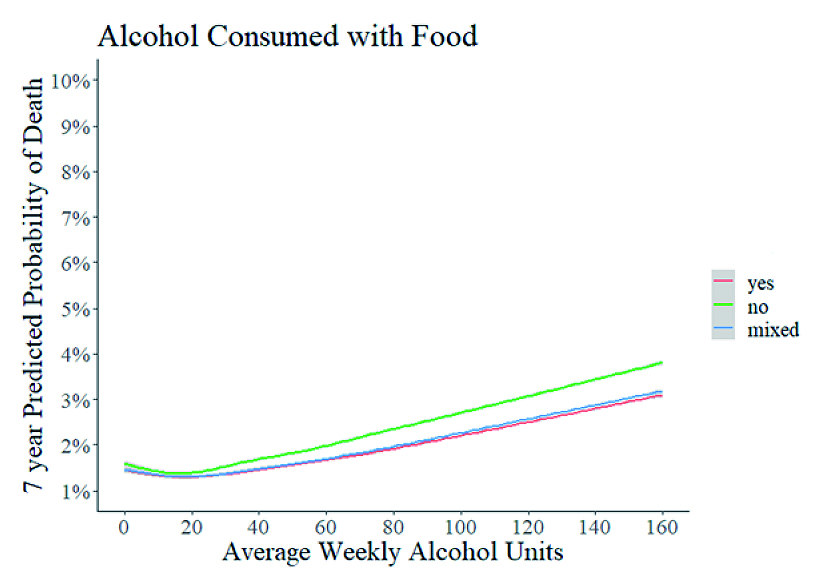

Remarkably, the results further revealed that alcohol consumption without food was associated with a higher adjusted mortality risk (HR: 1.10) compared to consumption with food (Figure 3). Besides, alcohol consumption over 1¡V2 times/week had higher adjusted mortality (HR: 1.09) and MACE risk (HR: 1.14), compared to 3¡V4 times/week, adjusting for the amount of alcohol consumed. Hence, the study concluded that red wine drinking, consumption with food and spreading alcohol intake over 3¡V4 days were associated with a lower risk of mortality and vascular events among regular alcohol drinkers13.

Figure 3. Predicted probability (7-year) of mortality13

Undoubtedly, alcohol is a major risk factor for liver cirrhosis, with risk increasing exponentially14. In this regard, heavy alcohol consumption should be avoided. So, how about low-to-moderate alcohol consumption? Some comments may say that there is no safety level for toxins. Nonetheless, as outlined above, clinical data have demonstrated the health benefits of moderate wine consumption. It is noteworthy that recent clinical data have shown favourable effects of initiating moderate wine consumption on lipid biomarkers, components of the metabolic syndrome, blood pressure, and abdominal adipose tissue distribution among well-controlled persons with type 2 diabetes15. This highlights the potential benefits of moderate wine consumption, not only in healthy populations but also among people with chronic disease.

There is no easy recommendation on whether wine consumption should be promoted. Yet, there are pros and cons for most issues. For instance, it may be not realistic to avoid barbecuing simply for its associated health hazards. To conclude, whether you are a wine lover or not, it is always right to drink responsibly and remember the quote, “Too much of a good thing is bad.”

References

1. Burr. J R Soc Health 1995; 115: 217¡V9. 2. Buja. Cardiovasc Pathol 2022; 60. DOI:10.1016/J.CARPATH.2022.107446. 3. Barbalho et al. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2020; 60: 3876¡V89. 4. Copetti et al. J Nutr Metab 2018; 2018. DOI:10.1155/2018/4384012. 5. Magyar et al. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2012; 50: 179¡V87. 6. Rees et al. Nutrients 2018; 10. DOI:10.3390/NU10121852. 7. Guerrero et al. PLoS One 2012; 7. DOI:10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0049493. 8. Castaldo et al. Molecules 2019; 24. DOI:10.3390/MOLECULES24193626. 9. Huang et al. Molecules 2014; 19: 12827. 10. McCullough et al. Am J Clin Nutr 2012; 95: 454¡V64. 11. Lucerón-Lucas-Torres et al. Front Nutr 2022; 9: 863059. 12. Schutte et al. Clin Nutr 2020; 39: 3168¡V74. 13. Jani et al. BMC Med 2021; 19. DOI:10.1186/S12916-020-01878-2. 14. Roerecke et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2019; 114: 1574. 15. Golan et al. Eur J Clin Nutr 2019; 72: 55¡V9.