Professor of Psychiatry and Pharmacology

The University of Toronto

Bipolar disorders (BD) are complex group of severe and chronic disorders associated with impaired psychosocial functioning, disability, and mortality. Essentially, depressive episodes and symptoms dominate the longitudinal course of bipolar disorders and contribute substantially to the adverse outcomes of the disorders1. While relatively few treatment options are shown to be effective and safe for BD, the management of the disorders remains a clinical challenge. In the Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society for Advancement of Bipolar Affective Disorder (SABAD) organised on 14th Jun 2023, Prof. Roger S. McIntyre discussed the clinical management of BD and major depressive disorder (MDD), with a specific focus on the diagnostic and treatment considerations.

Prof. McIntyre reminded us of the complexity of BD disorders and how they can be subclassified into BD-1, which is defined by the presence of a syndromal and manic episode, and BD-2, which is characterised by the presence of a hypomanic episode1. While BD-2 appears to receive less attention than BD-1, Prof. McIntyre highlighted BD-2 being common and severe. For instance, the proportion of morbidities involved in the depressive states of BD-2 are much higher than that of BD-1 (81.2% vs 69.6%)2. “Certain morbidities such as migraine, is more common in BD-2 compared to BD-1,” according to Prof. McIntrye.

Provided that there are no signature biomarkers available to guide the diagnosis, prognosis, or treatment outcome in BD disorders1, the probabilistic approach may help identify BD patients. Notably, various features, such as hyperphagia and leaden paralysis, are predominantly seen in BD-1 while reduced sleep and appetite are more common in unipolar depressive disorder3. According to Prof. McIntyre, the accumulation of the probabilistic factors may point towards the possibility of MDD with mixed features.

Depressive mixed state is defined by the presence of three or more intra-depressive hypomanic symptoms. More importantly, the mixed states substantially increase the risk of suicidal behaviour in both clinical and community patients, whereas the condition occurs frequently in BD and MDD4. Prof. McIntyre explained how symptoms of mixed states can be confusing for the clinicians and may lead to an assumed diagnosis of BD, which may in fact mask the actual true underlying cause. He clarified that individuals with BD presenting with depression will often manifest symptoms of 4 As, which is anxiety, agitation, anger-irritability, and attentional disturbance-distractibility, all of which are highly suggestive of mixed features1. Remarkably, Prof. McIntyre acknowledged that BD-2 is more susceptible to rapid cycling and mixed states. “The condition (BD-2) is not only common, it is also burdensome and less responsive to lithium and other well-known agents”.

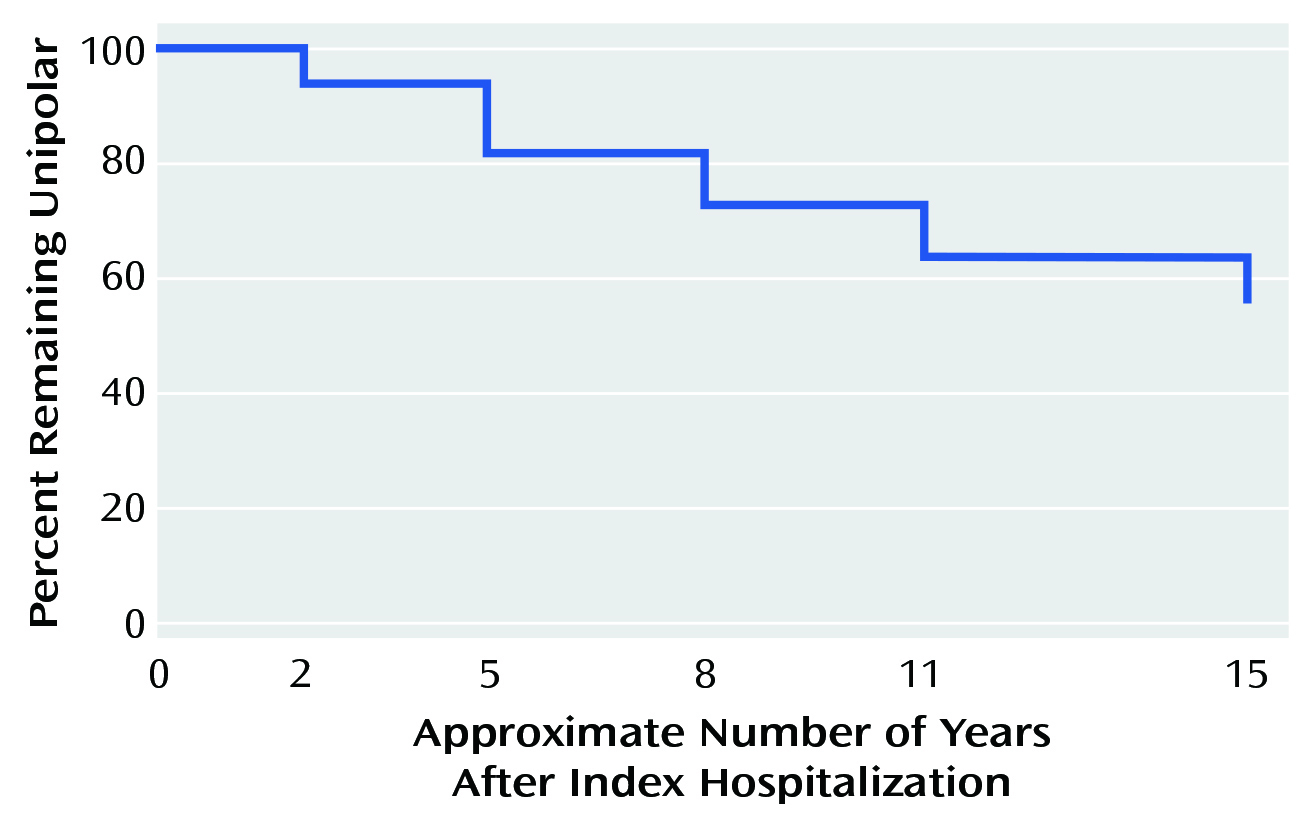

On the other hand, a cohort study by Goldberg et al. (2001) reported that 27% of patients who were hospitalised for unipolar major depression had developed one or more distinct periods of hypomania, while another 19% had at least one episode of full BD-1 mania (Figure 1). The study concluded that psychosis was a significant predictor of polarity conversion5. Therefore, Prof. McIntyre advised that it is paramount to screen for bipolarity in patients presenting depression, not only at the first console.

Figure 1. Survival analysis showing the proportion of patients remained unipolar over 15 Years5

Even though pharmacological treatments are the foundation for treating BD, Prof. McIntyre suggested that there are limited treatment options for both acute mania and maintenance phases of BD. “The most frequently prescribed drugs for acute mania in the United States are antipsychotics,” he stated. For maintenance treatment, Prof. McIntyre highlighted aripiprazole offering long-acting efficacy by delaying the onset of and reduce the recurrence of mania but not depression1. Notably, he also pointed out that the treatment options available for acute bipolar depression in local clinical settings are limited.

Moreover, the antidepressants frequently used in bipolar depression offers a modest clinical benefit. A meta-analysis by McGirr et al. (2016) involving 1,383 patients with bipolar depression showed that adjunctive second-generation antidepressants were associated with reduced symptoms of acute bipolar depression, but the magnitude of benefit was relatively small since they do not increase clinical response or remission rates. Furthermore, prolonged use of the antidepressants (e.g., 52 weeks) was associated with an increased risk of treatment-emergent mania or hypomania (odds ratio [OR]: 1.774, p=0.043)6.

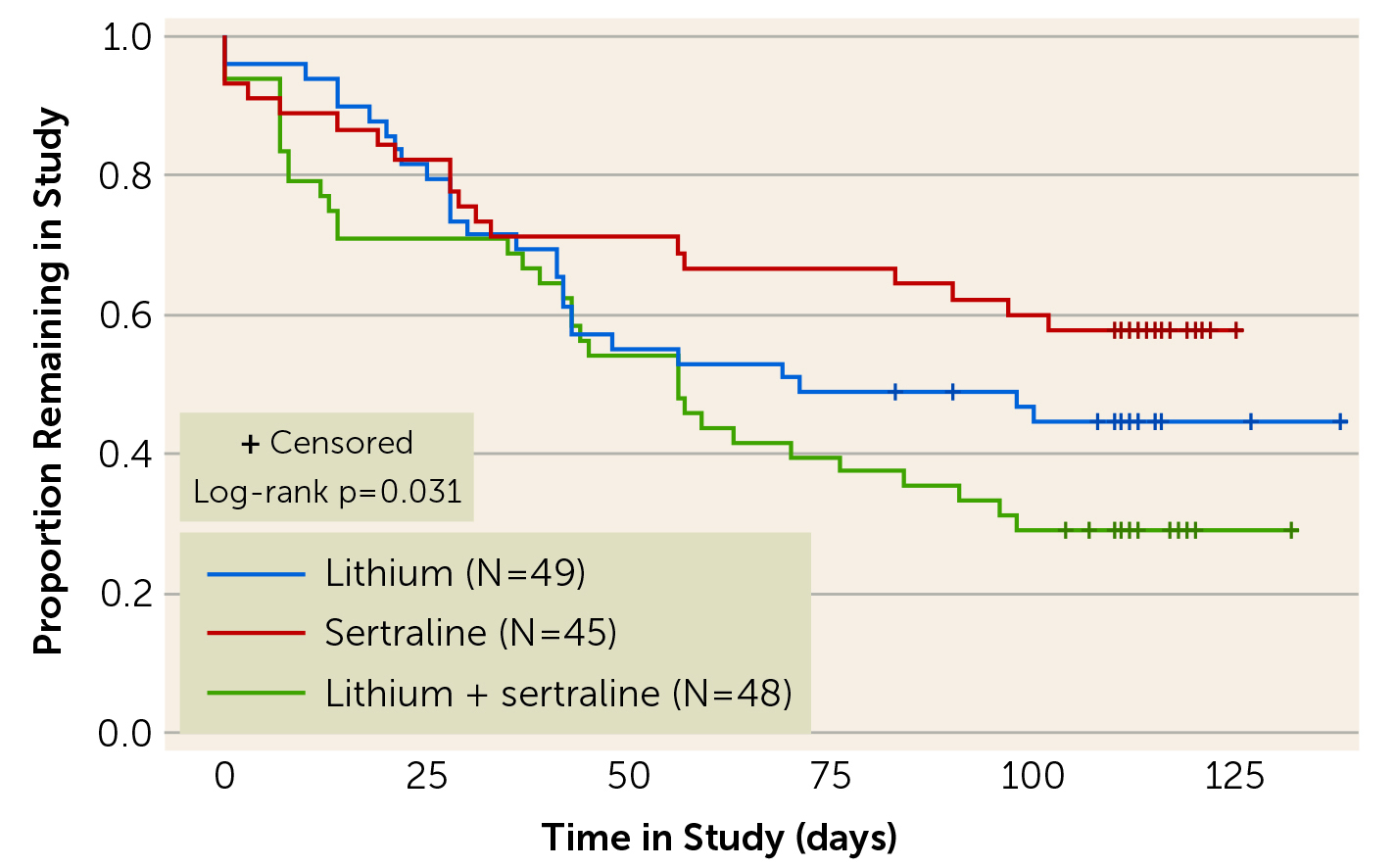

The unmet need in managing acute phase of bipolar-2 depression was made obvious in a randomised trial by Altshuler et al. (2017), which included 142 patients with bipolar-2 depression randomly assigned to receive lithium monotherapy, sertraline monotherapy, or lithium/sertraline combined treatment. The results showed that the treatment response rate for the overall sample was 62.7%; nonetheless 14% of the patients experienced a medication-induced mood switch. Unsurprisingly, the dropout rate was higher in the lithium/sertraline combination treatment group, without any treatment advantage over single agent use (Figure 2). Notably, the results also confirmed that patients with BD-2 had high rates of rapid cycling (41.6%)7.

Figure 2. The dropout over time in patients received lithium, sertraline, or both7

Thanks to the advances in recent drug development, controlling mood disorders, including those with mixed features has shown some promising results. For instance, Suppes et al. (2016) reported that 6-week treatment with lurasidone for MDD patients with mixed features showed significant improvement in depressive symptoms and the overall illness severity compared to placebo. Moreover, significant improvements in manic symptoms were also observed. More promising was that the rate of discontinuation of lurasidone due to adverse events which remained relatively low throughout the study8.

Cariprazine on the other hand is a dopamine D3-preferring D3/D2 receptor and 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist. A post hoc analysis of 3 randomised controlled trials (RCT) performed by Prof. McIntyre's team demonstrated that patients treated on a 6 weeks course of cariprazine (1.5 mg/day) yielded a significantly greater reduction in MADRS total score from baseline compared to placebo (least squares mean difference [LSMD]: -2.5, p = 0.0033). Moreover, a significant difference was also observed in patients without manic symptoms (LSMD: -3.3, p = 0.0008). Hence, the results were suggestive that cariprazine may be an appropriate treatment option for patients with BD-1 with or without manic symptoms9.

Other notable RCT by Calabrese et al. (2021) indicated significant MADRS superiority using lumateperone monotherapy over placebo at day 43 in patients with BD-1 and BD-210. Remarkably, Prof. McIntyre pointed out that even though quetiapine is the only drug available in local clinical settings, it has shown to be effective in both BD-1 and BD-2 depression.

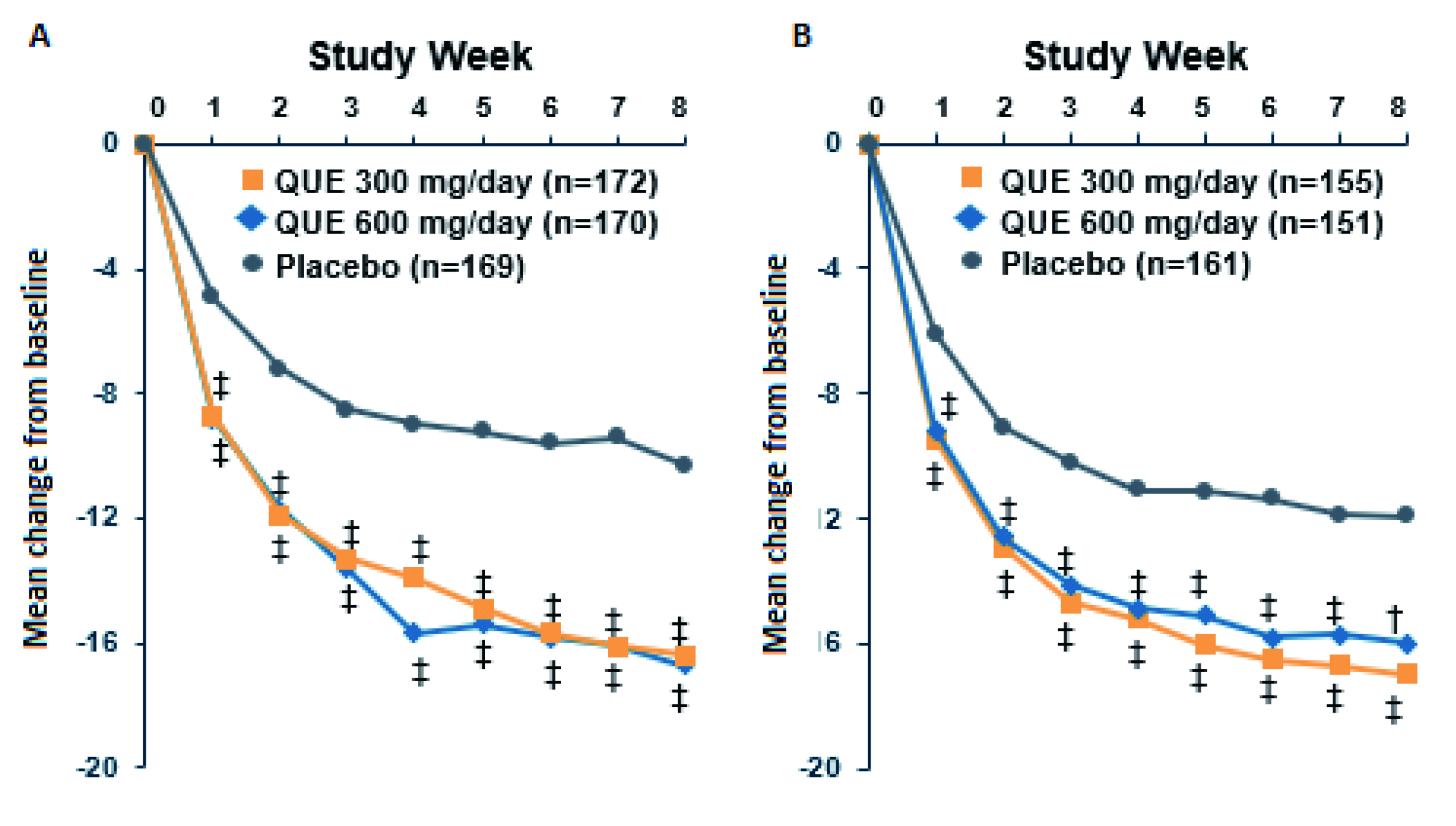

The efficacy and tolerability of quetiapine monotherapy (300 or 600 mg/d) for depressive episodes in patients with BD-1 or BD-2 were demonstrated in the BOLDER trials. In BOLDER I trial, 542 patients with BD-1 (N=360) or BD-2 (N=182) experiencing a major depressive episode were randomly assigned to 8 weeks of quetiapine or placebo in outpatient setting. The results showed that the proportions of patients meeting remission criteria (MADRS≤12) were 52.9% in the groups taking quetiapine versus 28.4% for placebo. Essentially, quetiapine significantly improved depressive symptoms from baseline compared to placebo (Figure 3)11.

Figure 3. Changes from baseline in MADRS total score achieved by quetiapine in A) BOLDER I and B) BOLDER II trials 11,12, QUE: quetiapine, ‡p<0.001, †p<0.01

The findings in BOLDER I trial were substantiated in the BOLDER II trial that the results showed an improvement in mean Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) scores were more prevalent with quetiapine dose group (both 300 and 600 mg/d), than with the placebo group (p<0.001) as early as week 1 and throughout the study. The MADRS response and remission rates were also significantly greater in both quetiapine dose groups than placebo. Moreover, the results further demonstrated that quetiapine was well-tolerated12. Prof. McIntyre added that the extended-release formulation of quetiapine (XR) is also effective in managing bipolar depression as well.

Prof. McIntyre highlighted that the number needed to treat (NNT) value of quetiapine, both XR and immediate release (IR) formulations, for MADRS responders with bipolar depression was 6, which was comparable to those of lurasidone (NNT: 5) and olanzapine/fluoxetine (NNT: 4)13. “The single-digit NNT of the medications reflected their high overall therapeutic effects,” he commented.

Prof. McIntyre emphasised that ketamine is not only effective in unipolar disorder, but also BD. In fact, ketamine is effective in treating anxiety, irritability, and agitation (AIA) symptoms, which are commonly seen in patients presenting with both hypomanic and depressive symptoms. Of note, more severe mixed symptoms were associated with more severe AIA14.

In a retrospective analysis performed by Prof. McIntyre’s team in 2020, 113 patients with treatment resistant MDD or BD after meeting the AIA criteria received repeat doses of intravenous (IV) ketamine treatment. The results indicated that IV ketamine was effective in treating AIA and suicidal ideation in adults with treatment-resistant mood disorders14. In addition, ketamine has also shown to be effective and rapid-acting in attenuating symptoms of anhedonia15. The implications of anhedonia were highlighted in a meta-analysis by Gillissie et al. (2022) which revealed that anhedonia has a significant and moderate correlation with suicidality in general and psychiatric populations16. Therefore, this highlights the significance of controlling anhedonia when managing mood disorders.

Recently, a consensus of internationally recognised experts defined treatment-resistant bipolar depression as the failure to reach sustained symptomatic remission for 8 consecutive weeks after two different treatment trials, at adequate therapeutic doses, with at least two recommended monotherapy treatments or at least one monotherapy treatment and another combination treatment. In practice, treatment resistance has been reported in about 25% of patients with bipolar disorders17. While evaluating the risk factors for treatment resistance in mood disorders, Souery et al. (2007) identified that anxiety comorbidity was associated with a 2.6-fold increased risk of resistance to antidepressant (p<0.001)18. Similarly, Papakostas et al. (2008) reported that an increased number or severity of anxiety symptoms for patients with MDD can increase the likelihood of non-response to antidepressant treatment19. While switching to different types of antidepressants for inadequate response is recommended, a meta-analysis by Bschor and Baethge (2010) suggested that switching to another antidepressant was not superior to continuing the initial antidepressant20.

While co-morbid MDD and anxiety are reported to increase the risk of treatment resistance, Prof. McIntyre highlighted that efficacy and tolerability of once-daily quetiapine XR (150 or 300 mg/day) as monotherapy treatment for MDD. In fact, at week 6, both doses of quetiapine XR significantly (p<0.001) reduced mean MADRS total score when compared to placebo, and a significant reduction was seen at week 1 with both doses of quetiapine XR against placebo (p<0.01). Moreover, both doses of quetiapine XR yielded significantly higher (p<0.01) response rates than placebo at week 621. To further substantiate the efficacy of quetiapine XR, an RCT by Weisler et al. (2009) with 723 MDD patients showed that quetiapine XR rapidly alleviate symptoms of anxiety (p<0.05), as measured by the HAM-A total score at day 422. The results thus suggested that quetiapine XR is an effective, with rapid-onset, and a tolerable treatment for controlling MDD and anxiety.

In summary, Prof. McIntyre emphasised that quality of life and functional outcomes remains a priority when considering therapeutic approach in managing mood disorders. Integrating treatments in a shared decision manner would help optimise the clinical outcomes, whereas psychiatric and medical comorbidities should also be considered in parallel when conceptualising symptoms such as cognition, and anhedonia. In conclusion, selecting safe and well-tolerated second-generation antipsychotics effective in both MDD and BD is advocated.

References

1. McIntyre et al. Lancet 2020; 396: 1841–56. 2. Forte et al. J Affect Disord 2015; 178: 71–8. 3. Mitchell et al. Bipolar Disord 2008; 10: 144–52. 4. Popovic et al. Bipolar Disord 2015; 17: 795–803. 5. Goldberg et al. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158: 1265–70. 6. McGirr et al. Lancet Psychiatry 2016; 3: 1138–46. 7. Altshuler et al. Am J Psychiatry 2017; 174: 266–76. 8. Suppes et al. Am J Psychiatry 2016; 173: 400–7. 9. Mcintyre et al. CNS Spectr 2020; 25. DOI:10.1017/S1092852919001287. 10. Calabrese et al. Am J Psychiatry 2021; 178: 1098–106. 11. Calabrese et al. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 1351–60. 12. Thase et al. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006; 26: 600–9. 13. Citrome. Int J Clin Pract 2019; 73. DOI:10.1111/IJCP.13397. 14. McIntyre et al. Bipolar Disord 2020; 22: 831–40. 15. Nogo et al. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2022; 239: 2011–39. 16. Gillissie et al. J Psychiatr Res 2023; 158: 209–15. 17. Diaz et al. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry 2022; 44: 178. 18. Souery et al. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68: 1062–70. 19. Papakostas et al. J Clin Psychiatry 2008; 69: 5993. 20. Bschor et al. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2010; 121: 174–9. 21. Cutler et al. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70: 526–39. 22. Weisler et al. CNS Spectr 2009; 14: 299–313.