Pharmacist,

Head of Department of Pharmacology and Pharmacy,

The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Psychiatrist,

Chair of Developmental Mental Health,

University of Melbourne, Australia

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders in children, with an estimated global prevalence of 5–7% in school-aged children. It is characterised by hyperactivity and impulsivity with the inability to concentrate, resulting in functional impairment in academic, family, and social settings1. There is increasing evidence that the symptoms and impairments of ADHD can persist into adulthood for up to 65% of children with ADHD2. In the hybrid symposium titled “The Latest Updates on Guideline and Research of ADHD Treatment: From Australia and Hong Kong Perspectives”, organised by the Department of Pharmacology and Pharmacy of The University of Hong Kong on 24th May 2023, Prof. Ian CK Wong presented the research on maternal medication use, diabetes and the risk of ADHD in children, and Prof. David Coghill highlighted some key recommendations from the newly published Australian ADHD Guideline and discussed their relevance to everyday clinical practice.

Whether maternal use of antidepressants would increase the risk of ADHD in children is controversial since the findings from current literature have been inconsistent. Prof. Wong remarked on the potential issues of sample size and confounding factors. “(Some studies) have not controlled the parameters in mother, including mental illnesses, concurrent medication, and genetic factors,” he commented. Particularly, ADHD is highly heritable3 that the mental illnesses in the mother could be associated with the ADHD risk in children. To assess the potential association between maternal use of antidepressants and the risk of ADHD in offspring, a population-based cohort study was conducted by Prof. Wong's team (2017) using data from the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System in Hong Kong.

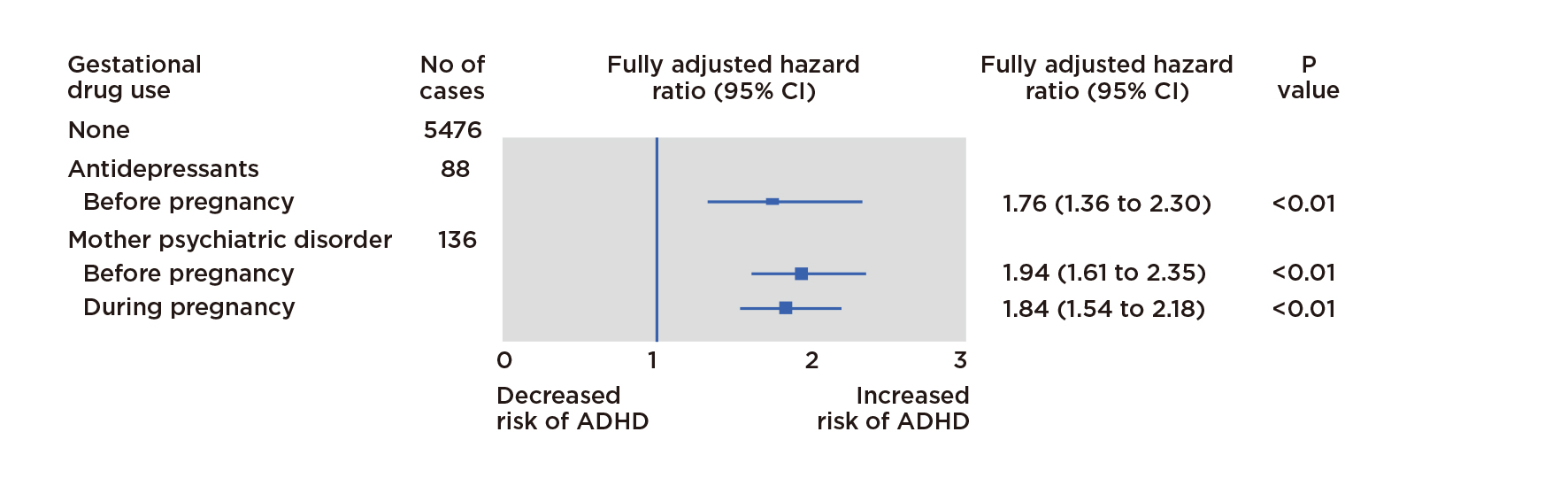

Among a total of 190,618 children analysed, 5,659 children (3.0%) were diagnosed with ADHD or received treatment for ADHD. After adjustment for potential confounding factors, the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of maternal antidepressant use during pregnancy for ADHD in children was 1.39 (p=0.01) versus non-use. Similar results were observed when comparing children of mothers who had only used antidepressants before pregnancy with those who were never users (adjusted HR: 1.76, p<0.01, Figure 1). The risk of ADHD in the children of mothers with psychiatric disorders was higher than in the children of mothers without psychiatric disorders and the mothers had never used antidepressants (adjusted HR: 1.84, p<0.01, Figure 1)4. The findings suggested that using antidepressants, both during and before pregnancy, would increase the risk of ADHD in offspring. He noted that the mother who used antidepressants before pregnancy had stopped the medication and the foetus should not be affected by the antidepressants. Thus, the use of antidepressants is not necessarily the true cause of the increased risk of ADHD in children, whereas the increased risk may have been confounded by maternal or familial factors.

Figure 1. Adjusted HRs for ADHD in children5

A subsequent meta-analysis (2018) confirmed a significant association between maternal psychiatric conditions and ADHD in children (adjusted rate ratio [RR]: 1.90). Also, an increased risk was found comparing previous antidepressant users and non-users (adjusted RR: 1.56) but the sibling-matched analyses showed no significant increased risk of ADHD in discordant exposed siblings5. Prof. Wong commented that the observed association between maternal use of antidepressants and the risk of ADHD in offspring could be partially explained by confounding by the ADHD or other mental illnesses related to ADHD of the mother. Similar observations in recent studies on maternal antipsychotics, benzodiazepines and Z-Drugs use during pregnancy were observed6,7.

Prof. Wong presented that the global prevalence of maternal diabetes mellitus (MDM) has been increasing and previous study suggested that MDM may be associated with an increased risk of ADHD in offspring. Nonetheless, the findings were inconsistent1. An international retrospective cohort study was conducted by his team to assess the association between exposure to MDM and the risk of ADHD in offspring. The results showed a significantly higher risk of ADHD by 14% in children of mothers with MDM compared to those of non-MDM mothers and demonstrated no significant difference in the risk of ADHD between children exposed to gestational DM (GDM) and their siblings who did not. "This means that when a child born to the mother who had diabetes, compared to the sibling born in a mother did not develop GDM, there is no difference," he emphasised. He concluded that a slight increase in the risk of ADHD was found in children born to mothers with diabetes. However, according to sibling analysis, the association for GDM may be confounded by shared genetic and environmental familial factors.

The Evidence-Based Clinical Guideline for ADHD published by the Australian ADHD Professionals Association (AADPA) aims to promote accurate and timely diagnosis and provide guidance on optimal and consistent assessment and treatment of ADHD. Prof. Coghill highlighted that the ultimate aim of treating ADHD is to improve patients’ lives but not just improving symptoms. Improving patients’ understanding of ADHD and its treatments would promote better outcomes8. Therefore, psychoeducation is essential in ADHD treatment. Reducing symptoms of ADHD and co-existing disorders, and improving functionality and wellbeing are also the objectives of ADHD treatment advocated in the AADPA Guideline9.

Clinicians should explain to people with ADHD and their families the components of multimodal treatment, including pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions9. Parent/family training should be focused on education about the cause of ADHD and its impacts on functioning. The roles of environmental and behavioural modifications in reducing the impacts of ADHD symptoms are highlighted9. Prof. Coghill presented the concept of ADHD coaching, an emerging approach that shares common elements with cognitive behavioural interventions, particularly with the approaches to environmental modification and behavioural change9. “(ADHD coaching) is a bit like ADHD-specific occupational therapy with counselling,” he explained.

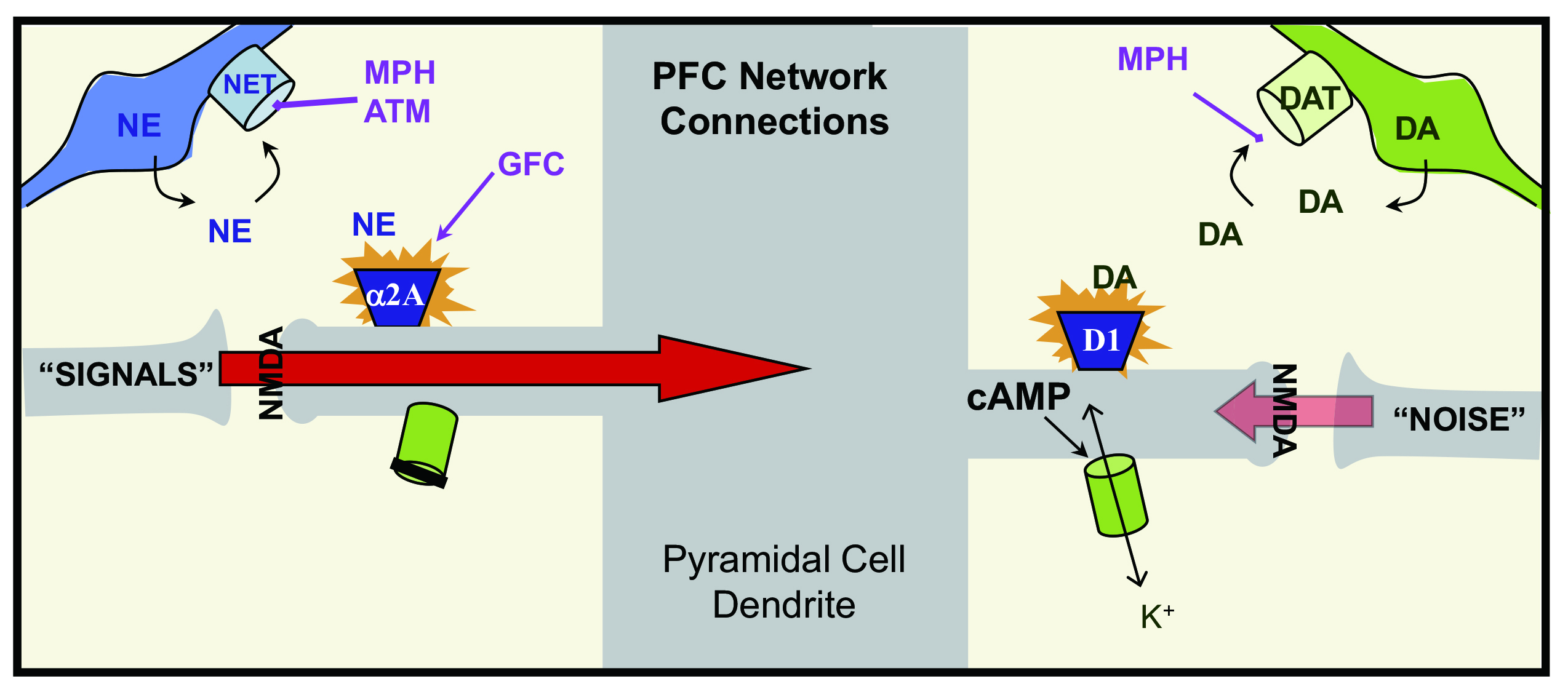

A meta-analysis by Prof. Coghill's team indicated that lisdexamfetamine (LDX) appeared to have a larger effect size than methylphenidate (1.02 vs 0.78) on ADHD core symptoms compared with placebo. Additionally, the effect size yielded by guanfacine (GFC) was 0.6710. “In almost all situations, a stimulant will be the appropriate first-line medication for ADHD”, he noted. LDX is long-acting and has demonstrated efficacy at 13 hours post-dose. The therapy is reported to be well-tolerated generally, with a safety profile consistent with long-acting stimulant use11. Non-stimulants would be used when stimulants are not responded to or tolerated and is also considered if there is active concern about substance misuse or in the presence of psychosis, bipolar disorder, or tics. Prof. Coghill presented that GFC is a treatment option for children and adolescents with ADHD to achieve improved outcomes. Biologically, GFC is a selective 2A-adrenoceptor agonist, and this selectivity is believed to account for the less sedating and hypotensive profile12. GFC directly mimics norepinephrine beneficial actions at postsynaptic 2A-adrenoceptors in the prefrontal cortex (Figure 2)13 so GFC is the only ADHD medication that has no effect on dopamine and the prolonged-release GFC formulation (GFC-XR) was designed to be less soluble in the stomach than the immediate-release formulation, resulting in slow, sustained release and absorption.

Figure 2. Working model of catecholamine actions on prefrontal cortex circuits at the molecular level13, ATM: atomoxetine, DA: dopamine, MPH: methylphenidate, NE: norepinephrine, NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate, PFC: prefrontal cortex (source of figure: Arnsten and Rubia, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2012)

GFC can be used as a standalone monotherapy where stimulants are ineffective, contraindicated, or not tolerated, and can be prescribed as adjunctive therapy when suboptimal effects are observed with stimulants. Practically, GFC-XR is a once-daily formulation. “Starting GFC-XR is really easy with 1mg for a week, followed by 2mg in week 2. Then, titrate up to 3mg for 4 weeks. If no response is achieved at the end of week 7, stop treatment should be considered. Increase to 4mg is recommended if a partial response is obtained,” Prof. Coghill described.

The clinical data presented by Prof. Wong visualised the confounding effect of maternal or familial factors on the spurious association between maternal exposure to psychotropic drugs and the risk of ADHD in children. Psychotropic medications might not be necessarily the true cause of the increased risk of ADHD in children. A slight increase in the risk of ADHD was found in children born to mothers with diabetes but the association to GDM might be confounded by shared genetic and environmental familial factors. Besides, the AADPA Guideline addressed the importance of psychoeducation and environmental and behavioural modifications in improving overall patient outcomes instead of treating ADHD symptoms. While pharmacological intervention is a vital component in the management of ADHD, Prof. Coghill emphasised the role of stimulants as the first-line medication for ADHD. The long-acting efficacy of LDX is particularly highlighted. The pharmacological advantages and practical simplicity of GFC make it an ideal option for managing ADHD.

References

1. Zhao et al. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2019; 15: 675. 2. Raman et al. Lancet Psychiatry 2018; 5: 824–35. 3. Grimm et al. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2020; 22. DOI:10.1007/S11920-020-1141-X. 4. Man et al. BMJ 2017; 357. DOI:10.1136/BMJ.J2350. 5. Man et al. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2018; 86: 1–11. 6. Chan et al. Psychother Psychosom 2023; 92: 1–11. 7. Wang et al. JAMA Intern Med 2021; 181: 1332–40. 8. Kamimura-Nishimura tal. Curr Psychiatr 2019; 18: 25. 9. AADPA. Australian Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline for ADHD. 2022. 10. Coghill et al. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2021. DOI:10.1007/S00787-021-01871-X. 11. Mattingly et al. CNS Spectr 2010; 15: 315–25. 12. Spencer et al. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2009; 19: 501. 13. Arnsten et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012; 51: 356–67.