Head of Oncological Gynecology

La Fe Hospital

Valencia, Spain

Intraoperative haemorrhage has been reported in 1-2% of hysterectomies. The condition is defined as a blood loss of more than 1000ml during surgery or any blood loss requiring a blood transfusion. Essentially, a blood loss of more than 40% of the patient's blood volume is life-threatening unless resuscitation is accomplished promptly1. Thus, proper preparation, planning, and practising for an intraoperative haemorrhage, especially a massive haemorrhage, is essential for all surgeons. Given the complex anatomical structure of the pelvis, gynaecologic surgeries are susceptible for perioperative bleeding. In a recent sharing, Dr. Santiago Domingo of the La Fe Hospital, Spain, shared his experience and opinions on haemostatic methods in gynaecologic surgical procedures.

While the management of bleeding is crucial in any surgery, Dr. Domingo emphasised its clinical significance in gynaecologic oncology, given the complex structure of the pelvis, where many vessels are situated. “The large number of deep vessels in the retroperitoneum can complicate our life in the operation theatre”, Dr. Domingo expressed. He outlined the 4 main scenarios of surgeries in gynaecologic oncology: surgical staging, advanced ovarian cancer, retroperitoneal debulking, and surgery after radiotherapy. In particular, Dr. Domingo noted that surgery after radiotherapy would be the most challenging scenario because it involves surgical procedures deep in the retroperitoneum. For instance, the procedures of laterally extended endopelvic resection (LEER) for the treatment of recurrent cervical cancer involve the resection of iliac artery and vein, pelvic muscle, and so on2. Accordingly, there is a high risk of massive bleeding during the resection of tumours, whereas the reported median blood loss in LEER ranges from 300-1,600ml2,3.

Dr. Domingo addressed that, instead of young patients with good body mass index, surgeries are often performed in patients who are more difficult to manage, including obese, at older ages, with co-morbidities such as anaemia or hypoproteinemia, and/or have previous surgeries. “(For patients with bleeding risk factors mentioned), this is our task to recover and prepare them before the surgery. In particular, it is mandatory that patients go to surgery without anaemia and with a good protein level,” Dr. Domingo remarked. He reminded that a substantial proportion of bleeding cases are associated with acquired coagulopathy4.

Undoubtedly, increased perioperative blood loss would disrupt the surgical operation, impair organ exposure, and contribute to prolonged surgical and hospitalisation times. The condition would also increase the need for transfusion and extra therapy costs5. Yanazume et al (2018) retrospectively evaluated the prognostic impact of tumour bleeding requiring intervention during radiotherapy in 196 patients with cervical cancer. The results indicated that bleeding significantly correlated with lower progression-free survival (PFS, p=0.015, Figure 1) and overall survival (OS, p=0.048) compared to the non-bleeding group6. “Bleeding is a negative factor for the oncological outcome of any organ,” Dr. Domingo commented.

Figure 1. PFS of patients in bleed and non-bleeding groups6

While perioperative bleeding would increase the need for transfusion, a retrospective analysis by Prescott et al (2015) involving clinical data of 8,519 patients with gynecologic cancers reflected that transfusion was associated with higher composite morbidity, surgical site infections mortality and length of hospital stay7. Besides, Dr. Domingo revealed that gynaecological surgical patients had increased risks for developing deep venous thrombosis (DVT) because they experience hypercoagulable states, immobility and vascular injuries during their surgeries8. “When bleeding occurs during operation, you would do more stitches. However, the stitching would damage the endothelium of vessels and, in turn, increase the risk of thrombosis,” he stated. Of note, it has been reported that the incidence of postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE) in ovarian cancer was 13.2%, of which 71.6% was DVT, and pulmonary embolism (PE) accounted for 24.3%, whereas 4.1% suffered both9. From above, the burden associated with the increased perioperative blood loss is substantial, and prompt control of bleeding is thus vital.

Sharpening the surgical skills of surgeons with qualified and organised training is crucial in reducing the risk of perioperative bleeding. Nonetheless, Dr. Domingo noted that solely comprehensive training is not enough to minimise the risk of complications in surgeries. He advocated the prevention with Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols. The key elements of ERAS protocols include preoperative counselling, optimisation of nutrition, standardised analgesic and anaesthetic regimens and early mobilisation10. One of the key objectives of ERAS is to get the patient prepared for the surgery. The ERAS protocols require the surgeon to work with the patients and a team of healthcare professionals, particularly anaesthetists and nurses. Additionally, Dr. Domingo stated that innovative instruments are also essential in optimising surgical outcomes.

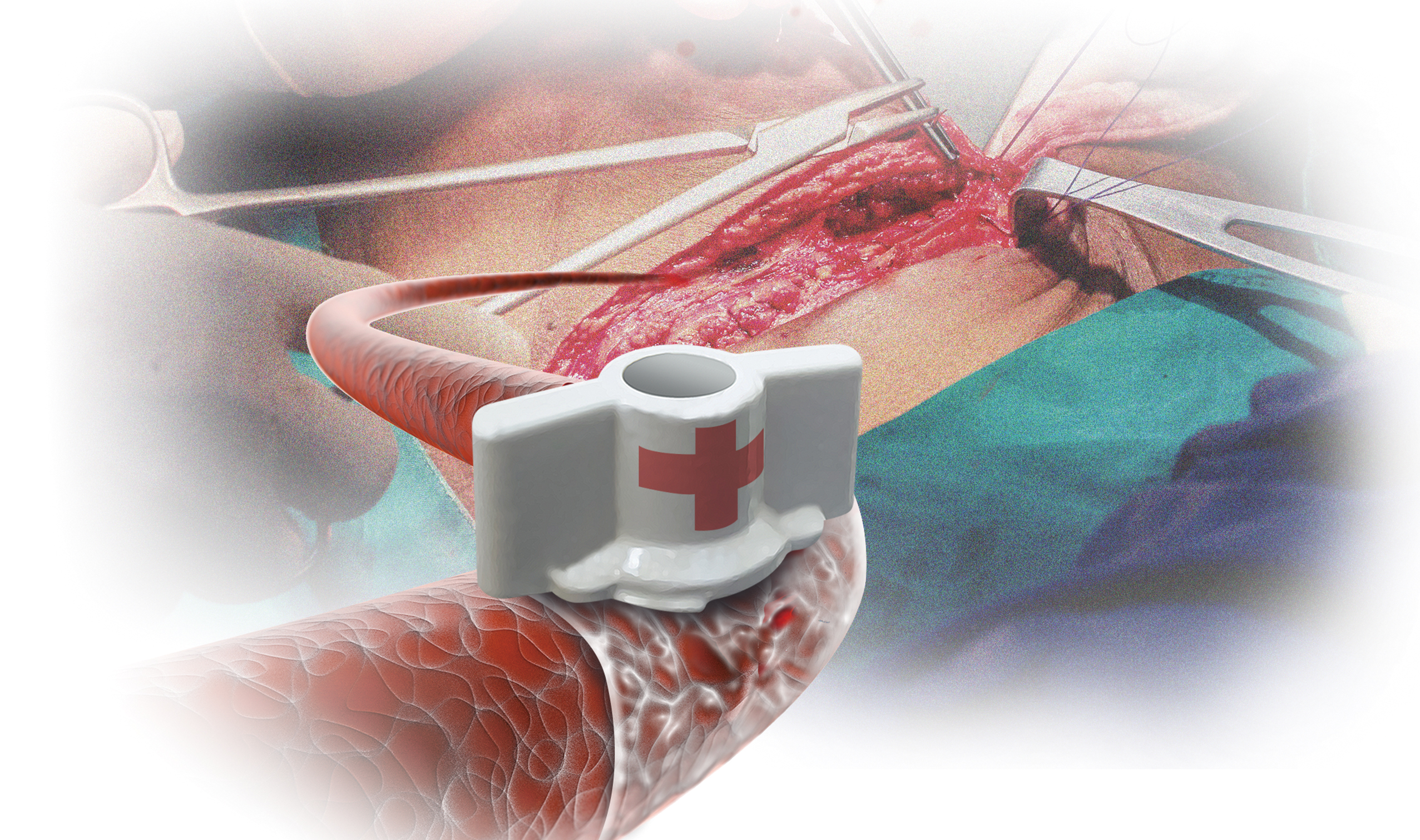

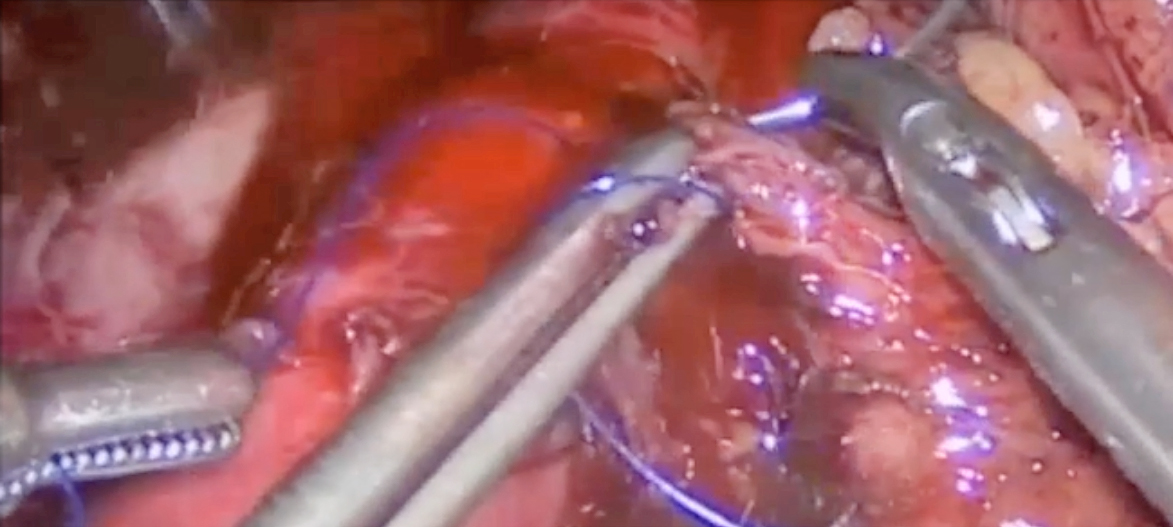

In case of bleeding in surgery, particularly in the retroperitoneal, proper communication among the surgeon, anaesthetist, and nurse is important. Dr. Domingo emphasised that the first job of the surgeon is to minimise blood loss by closing the injured vascular area, while the most convenient tool is his/her finger. Other proper instruments include clips and monopolar or bipolar sealers (Figure 2A). “The aim of primary haemostatic methods is to close the lumen of the vessel, which has already been opened, to prevent or to diminish bleeding,” he said. The second issue for the surgeon to consider is the anatomical structure of the region in which arteries and veins are being handled and hence to do exposition properly. Then, the surgeon has to manage suturing (Figure 2B).

A

B

Figure 2. Closing the opened aorta with (A) proper instruments followed by (B) suturing (figure presented by Dr. Domingo)

Dr. Domingo reminded that not all bleeding scenarios are the same and that surgeons would deal with irregular surfaces, diffuse bleeding, bad visualisation, high arterial pressure situations and so on. As mentioned, there are also bleeding risk factors associated with the patients. Therefore, secondary haemostatic methods would be required when primary haemostatic methods fail to control bleeding. He further highlighted that most surgeons choose haemostatic agents based on the site, i.e. the anatomical structure of the surroundings, and the bleeding situation, which concerns the type of access and tissue surface as well as the risk and intensity of bleeding.

The objective of applying secondary haemostatic agents is to achieve intraoperative haemostasis and to minimise postoperative risk. Dr. Domingo reminded that it is essential to know which haemostatic agent should be used in each specific scenario. He introduced that there are 4 types of secondary haemostatic agents. Of note, the passive mechanical haemostats and passive sealants contain no coagulation factors, whereas active non-mechanical haemostats and active sealants contain coagulation factors.

As stated, passive mechanical haemostats, such as oxidised regenerated cellulose, contain no coagulation factors but provide a mechanical barrier for platelet adhesion and initiate clots. On the other hand, the active non-mechanical haemostat contains thrombin so that it works by promoting the coagulation pathways and converting fibrinogen into fibrin to form a clot. The active sealants contain both thrombin and fibrinogen, which are combined at the time of application. Thrombin turns fibrinogen into fibrin and then forms a clot11. However, Dr. Domingo reminded that active sealants do not offer immediate mechanical support. Besides, passive sealants, such as cyanoacrylate adhesives, work by creating a physical seal but do not facilitate the initiation of clotting11.

Remarkably, Dr. Domingo highlighted an innovative fibrin-coated collagen sealant (FCCS) for controlling perioperative bleeding and leakage of fluids, such as bile and lymph. The FCCS contain both thrombin and fibrinogen for haemostasis and tissue sealing. Additionally, the FCCS consists of a collagen sponge which provides mechanical support. Thus, the FCCS makes use of the mechanisms of bioactive coagulation and physical sealing in achieving haemostasis12. Dr. Domingo claimed that the FCCS is very easy to keep in the operation theatre since it can be stored at room temperature and applied either directly to the tissue or moistened to increase flexibility.

The clinical benefit of FCCS in preventing postoperative complications after inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy for gynaecological malignancy was confirmed in the observational study by Buda et al (2016), which involved 49 patients accounting for a total of 74 inguinal dissections. The results demonstrated that patients treated with FCCS showed a significantly lower daily drainage volume (mean volume: 84ml) compared to the control group (mean volume: 143ml, p=0.004). The total drainage volume of the FCCS group (mean volume: 540ml) was lower than the control group (mean volume: 900ml, p=0.0001) as well13. Thus, Dr. Domingo opined that the FCCS had combined the advantages of all 4 types of secondary haemostatic agents in a single haemostat.

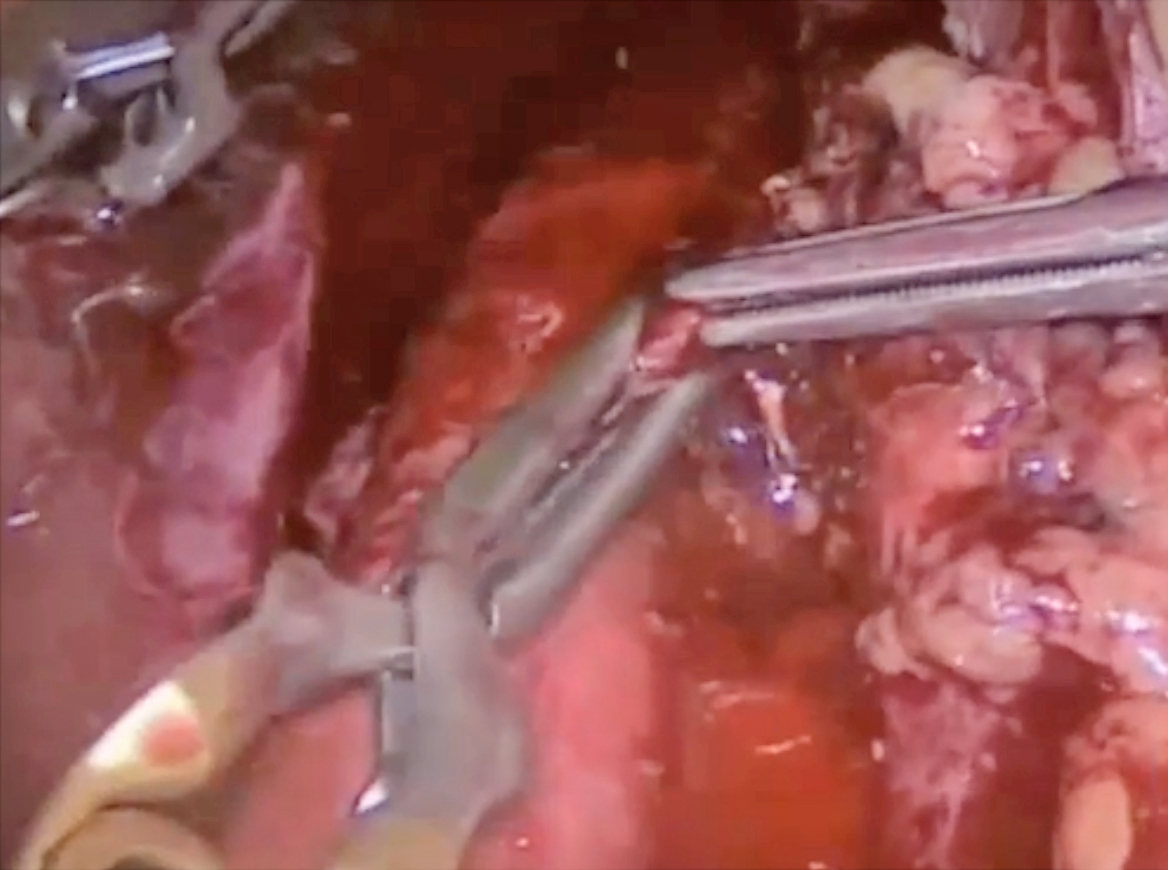

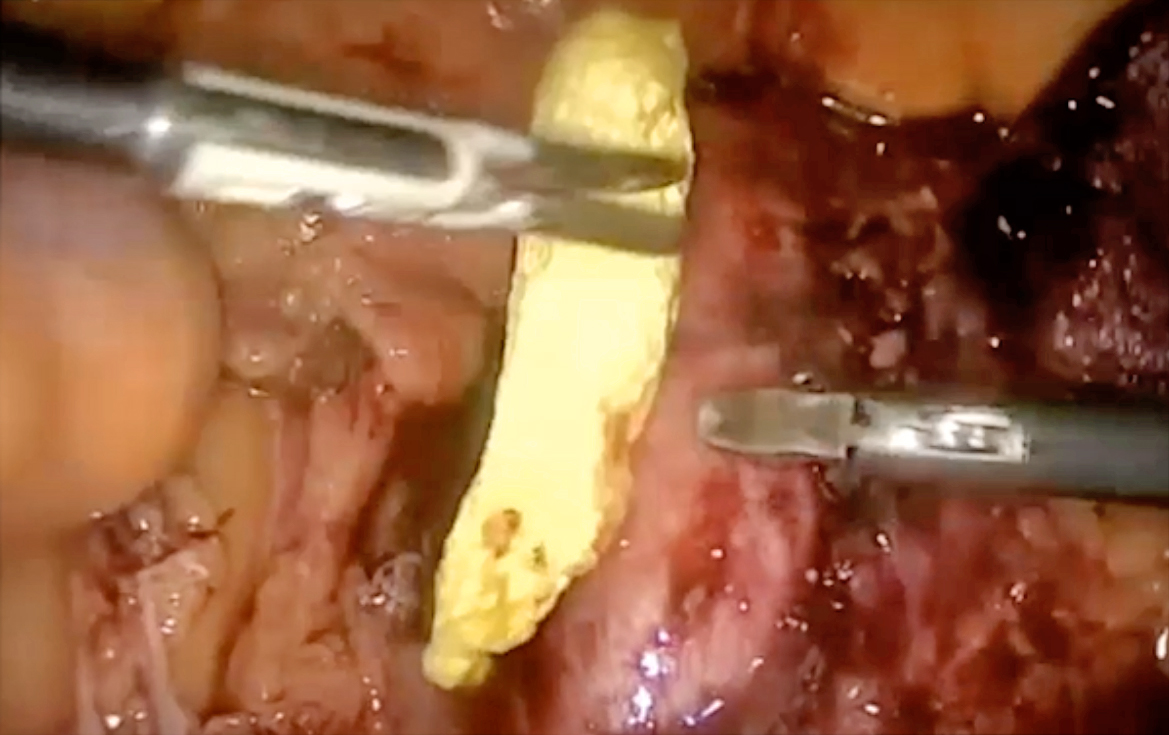

When applying FCCS during surgery, Dr. Domingo described that the FCCS could be cut to the required size and shape and placed in the proper place (Figure 3A). Then, open the FCCS and place it in the active area with the yellow side coated with thrombin upon the injury site (Figure 3B). He added that the FCCS can be pressed and rolled to facilitate the placing inside the abdomen. Notably, there is no defrosting and mixing procedure required in applying FCCS. A former clinical study suggested that haemostasis can be achieved with FCCS in 3 minutes in most cases14.

A

B

Figure 3. The application of FCCS at a bleeding site (figure presented by Dr. Domingo)

Dr. Domingo emphasised that doing surgery requires teamwork of healthcare professionals. Surgeons have to be trained to handle intraoperative haemorrhage and be mentally prepared for surgery. It is vital to stay calm when a haemorrhage occurs. Furthermore, as not all bleeding scenarios are the same, a better understanding of the haemostasis mechanism would help guide the best indication for haemostatic agents.

References

1. Yu et al. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2015; 58: 718–31. 2. Park et al. Obstet Gynecol Sci 2022; 65: 355–67. 3. Yao et al. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2022; 102: 2026–9. 4. Ghadimi et al. BJA Br J Anaesth 2016; 117: iii18. 5. Watrowski et al. In Vivo (Brooklyn) 2017; 31: 251. 6. Yanazume et al. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2018; 48: 892–9. 7. Prescott et al. Gynecol Oncol 2015; 136: 65–70. 8. Zhang et al. Pakistan J Med Sci 2015; 31: 453. 9. Kim et al. Healthc 2020, Vol 8, Page 48 2020; 8: 48. 10. Melnyk et al. Can Urol Assoc J 2011; 5: 342. 11. Pereira et al. Rev Col Bras Cir 2018; 45. DOI:10.1590/0100-6991E-20181900. 12. Rickenbacher et al. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2009; 9: 897–907. 13. Buda et al. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2016; 197: 156–8. 14. Maisano et al. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009; 36:708–14.