Global estimates suggest that over 310 million surgeries are performed each year. Among patients undergoing major surgery, 7-15% will experience a postoperative complication and the overall postoperative mortality rate varied from 0.79 to 5.7%1. In particular, perioperative bleeding accounts for 23% of surgical adverse events2 and is associated with a high rate of death, complications and healthcare resource use. In addition to proper surgical techniques, haemostasis is a crucial component governing surgical outcomes in all operative fields. Within the broad spectrum of surgical tools and treatments developed for controlling perioperative bleeding, a unique fibrin-coated collagen sealant (FCCS) with the dual action of bioactive coagulation and sealing has been shown to effectively reduce postoperative bleeding and leakage of fluids, such as bile and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Advancement in biomedical technology has nourished the development of a wide variety of topical haemostatic agents, such as absorbable topical haemostats and biologically active topical haemostats. Certain absorbable topical haemostats, such as oxidised regenerated cellulose, act by providing a physical matrix for initiating clots and creating an acidic environment enhancing the antimicrobial effect. In contrast, biologically active topical haemostats, such as fibrin sealants, promote clot formation by combining thrombin and fibrinogen, leading to the generation of fibrin at the time of application3.

Topical haemostatic agents would certainly help control perioperative bleeding, regardless of the mechanism of action. In particular, the innovation of FCCS has combined the advantages of bioactive coagulation and physical sealing in a single topical haemostatic agent. The FCCS consists of a collagen sponge coated on one side with fibrinogen and thrombin, and riboflavin coated on the same side gives it an indicative yellow appearance. While storing under refrigeration or freezing is required for some haemostatic agents, FCCS can be stored at room temperature. The FCCS can be applied either directly on the tissue or can be moistened to increase flexibility. It can be enzymatically degraded and safely absorbed by the body within approximately 24 weeks of application4.

The FCCS seals the tissue by mimicking the final steps of the natural blood clotting process. Upon the conversion from fibrinogen to fibrin by the action of thrombin, double-stranded protofibrils are formed and aggregate to form the fibrin cloth in the presence of endogenous Factor XIII. Remarkably, the microscopic honeycomb-like structure of collagen fleece of FCCS supports the sealing by providing anchorage for the fibrin clot. In addition, the collagen fleece ensures the fluid- and air-tight condition and absorbs fluid from the wound site4. Hence, the FCCS controls the risk of perioperative bleeding and improves surgical outcomes via the dual mechanisms of bioactive coagulation and physical sealing.

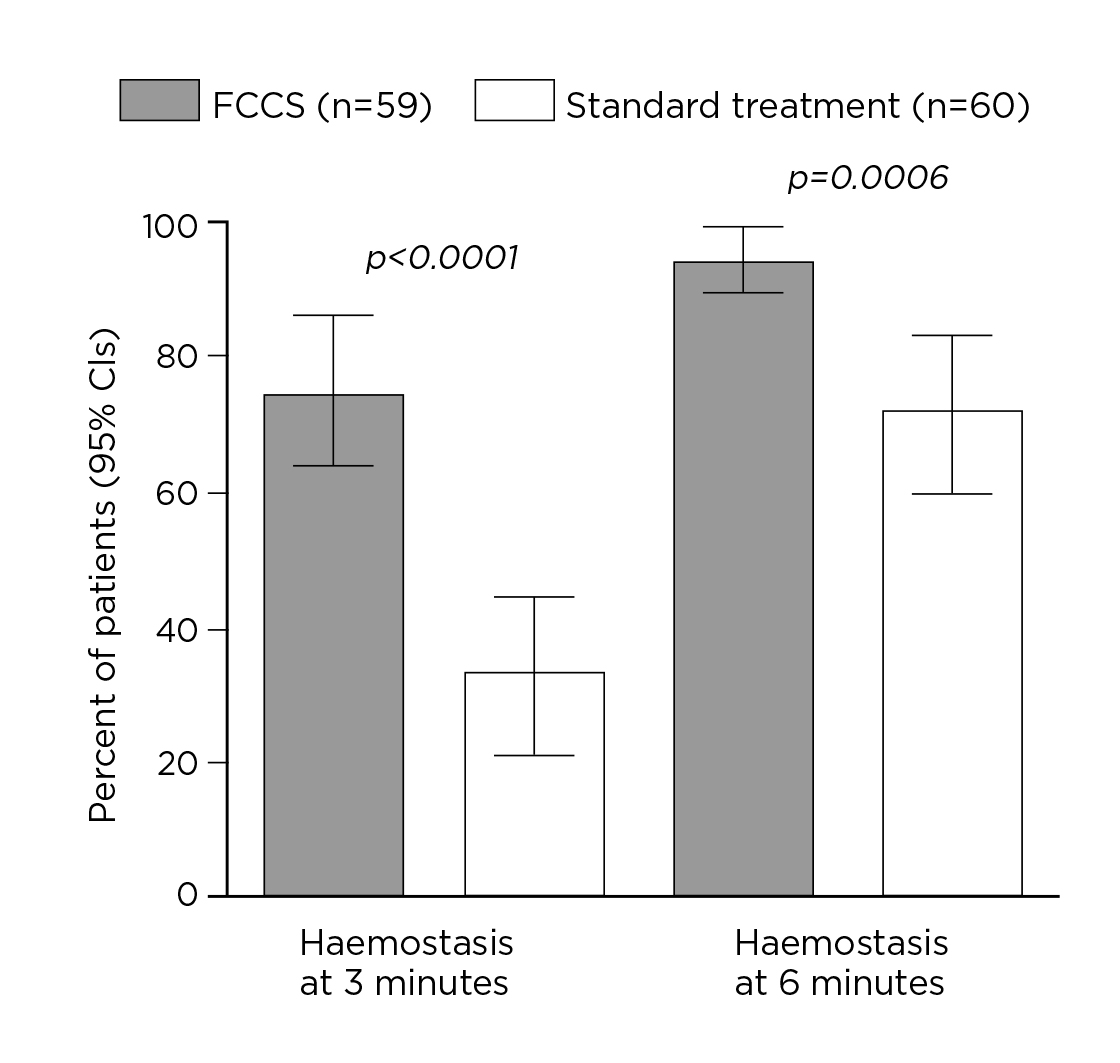

The clinical performance of FCCS in various operative fields has been evaluated in previous studies. For instance, Maisano et al (2009) compared the efficacy and safety of FCCS and standard haemostatic fleece to control bleeding in patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery. Among the 119 patients scheduled for elective surgery on the heart, ascending aorta or aortic arch requiring cardiopulmonary bypass, 59 were allocated to receive FCCS and the remaining received standard treatment after primary haemostatic measures. The results demonstrated superior efficacy in controlling bleeding in FCCS-treated patients after insufficient primary haemostasis compared to standard treatment. Remarkably, 75% of FCCS-treated patients achieved haemostasis at 3 minutes, whereas that achieved by standard treatment was only 33% (p <0.0001). Moreover, 95% of patients in the FCCS group achieved haemostasis at 6 minutes, significantly higher than standard treatment (72%, p=0.0006, Figure 1). The results indicated no significant differences in the occurrence of adverse events between the trial treatments5.

Figure 1. Proportions of patients with haemostasis at 3 and 6 minutes5

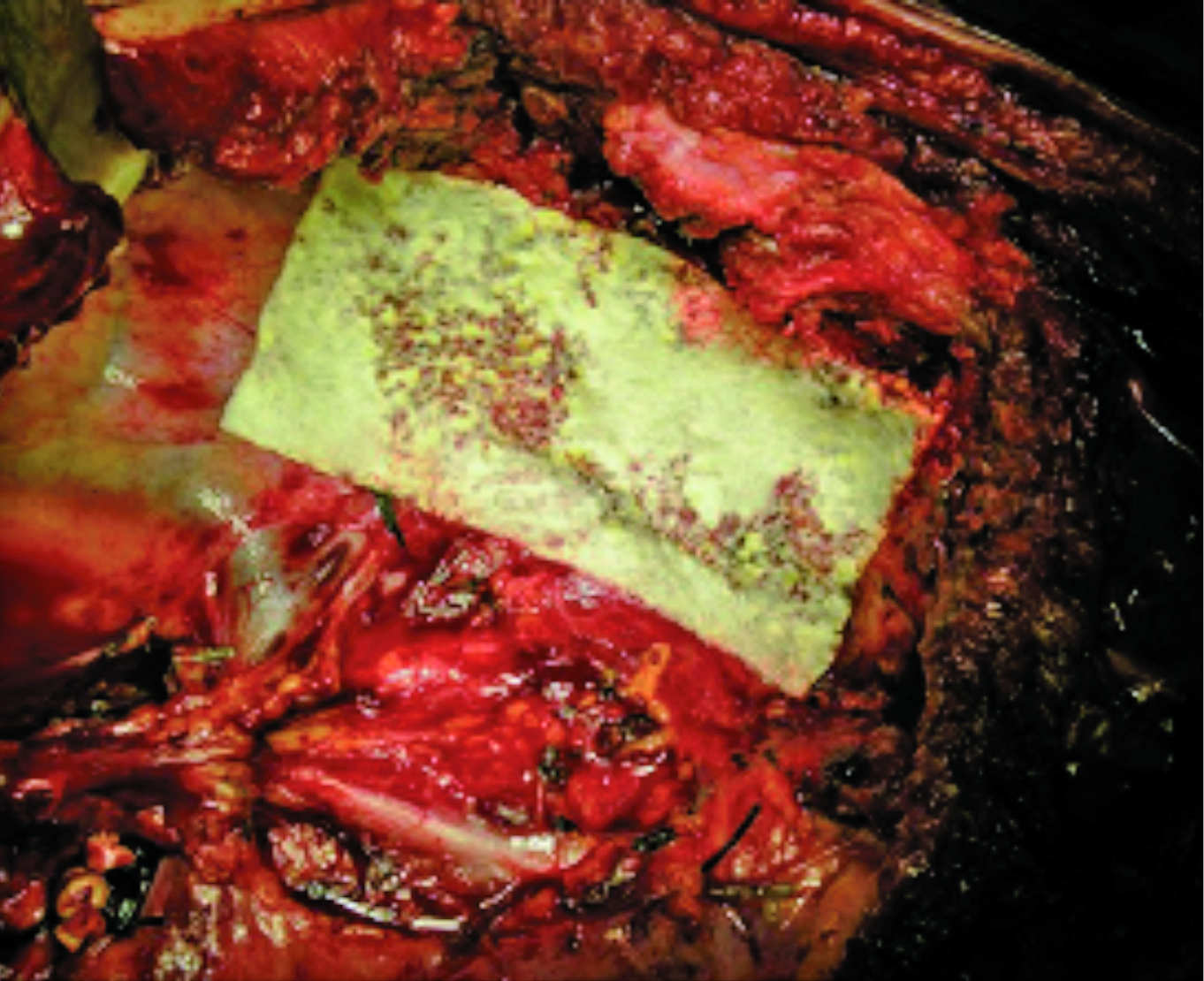

The effectiveness of FCCS in controlling diffuse bleeding following major resections with the requirement of chest wall and vertebral body resection was further illustrated in the case-series study by Filosso et al (2016), which involved 3 cases of pulmonary lobectomy associated with chest wall resection and haemivertebrectomy for primary malignant lung neoplasms and a recurrence of malignant solitary fibrous tumour of the pleura. Diffuse bleeding on the resected spine body surface occurred in all cases and was managed through traditional haemostatic aids, such as hot swabs and electrocautery, followed by the apposition of a large size FCCS (Figure 2). Notably, the report suggested that FCCS not only reduced the air leak volume but allowed an early removal of chest drains, a speedy recovery and an early discharge from the hospital6. This implied the potential benefit of FCCS in reducing the risk of postoperative clinical complications and overall hospitalisation costs.

Figure 2. FCCS placement after right upper lobectomy with chest wall and spine resection6 (Source of photo: Filosso et al, 2016)

Besides cardiothoracic surgeries, a recent cohort study by López-Guerra et al (2019) compared the effectiveness and complications of FCCS in controlling postoperative bleeding and biliary leak after liver resection with another haemostatic agent (“Hemopatch”). The results reflected no significant differences in effectiveness between the two haemostatic agents in terms of the requirement of intraoperative and postoperative blood transfusion, bile leakage, length of hospital stay, and overall and specific postoperative complications. Notably, while no incidence of intraabdominal abscess was observed in FCCS, the condition was found in 11.9% of patients treated with Hemopatch (p=0.01)7. The results thus implied that FCCS would be a good option as topical haemostatic after liver resection.

Endonasal endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery (EETS) is considered safe and effective and is the preferred treatment for pituitary adenomas. However, CSF leakage remains a significant complication after EETS. In a retrospective study by Spitaels et al (2022), the efficacy of FCCS versus a dural sealant to prevent postoperative CSF leakage was compared. Upon reviewing 219 EETS for pituitary adenoma in 198 patients, intraoperative CSF leakage occurred in 47 cases (21.5%), whereas 33 postoperative CSF leaks were observed (15.1%). Of note, numerically fewer postoperative CSF leakage was observed in the FCCS group (7.7%) compared to dural sealant (18.2%, p = 0.062). Notably, only two patients required lumbar drainage, and no revision repair was necessary to treat postoperative CSF rhinorrhea in the FCCS group8. This suggested that FCCS would be a valuable method to prevent postoperative CSF leaks during EETS for pituitary adenoma resection.

Undoubtedly, perioperative bleeding and complications would induce substantial costs for patients and extra burden on healthcare services. In addition to clinical performance, an evaluation of the practical benefits generated by FCCS treatment for the patients and healthcare system is essential. A systematic review by Colombo et al (2014), involving 2,116 patients undergoing hepatic, cardiac, or renal surgery, suggested that the time for FCCS to achieve haemostasis (1-4 minutes) was significantly shorter than other techniques and haemostatic drugs analysed. The results further showed that FCCS significantly reduced the incidence of postoperative complications compared to standard surgical procedures. Translating clinical data into practical benefits, a significantly reduced length of hospital stay by 2.01–3.58 days was obtained with FCCS versus standard techniques9. Hence, by effectively improving haemostasis and promoting tissue sealing, FCCS would probably reduce medical expenses and clinical workload associated with perioperative complications and hospital stays.

From above, FCCS is an effective and safe treatment for controlling perioperative bleeding and fluid leakage associated with surgeries in various disciplines. Accordingly, the optimised surgical outcomes would lead to benefits for both patients and the healthcare system. Nonetheless, further clinical trial data are desirable to confirm the benefits of FCCS in certain operative fields.

References

1. Dencker et al. BMC Surg 2021; 21: 1–10. 2. Zegers et al. Patient Saf Surg 2011; 5. DOI:10.1186/1754-9493-5-13. 3. Pereira et al. Rev Col Bras Cir 2018; 45. DOI:10.1590/0100-6991E-20181900. 4. Rickenbacher et al. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2009; 9: 897–907. 5. Maisano et al. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009; 36: 708–14. 6. Filosso et al. J Thorac Dis 2016; 8: E152–6. 7. López-Guerra et al. Sci Reports 2019 91 2019; 9: 1–7. 8. Spitaels et al. Sci Rep 2022; 12. DOI:10.1038/S41598-022-12059-X. 9. Colombo et al. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2014; 10: 569.