Seconded to anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder (MDD) contributed to a significant disease burden at 3.4% of the global population in 2017. 1 Meanwhile, a surge in local prevalence has also been reported during the COVID-19 pandemic, reflecting worsened mental health by overwhelming distress from external environment.2 Data suggested that there was an increase in antidepressant prescription pharmacy claims during the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period.3 Medication may not be a must in MDD treatment but effective for most people living with the condition.4-6

Most currently used antidepressants act based on the adoption of monoamine hypothesis that depression comes from depletion in the levels of serotonin, norepinephrine, and/or dopamine in the central nervous system.7,8 As suggested by the name, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) increase serotonin activity through inhibiting the reuptake of the serotonin.8 Among all classes of antidepressants, SSRIs are generally accepted as the first-line of psychopharmacotherapy.6,9 This class of agent holds several advantages over tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), replacing it as the standard for first-line. First, SSRIs can be started at a therapeutic dose without many titrations.6 Second, comparable effectiveness to TCAs at outpatient settings has been shown.6 Third, they have a better safety and tolerability profile, even in overdose.6 Despite the attainment of success mentioned above, SSRIs still suffer from significant shortcomings. Estimated that up to half of MDD patients do not respond to SSRI therapy, and weeks or months may be required for the therapeutic effect to be shown.10 If there is an inadequate response, it is common to combine with another antidepressant or switch to it. Yet there remains a large proportion of MDD patients who failed to benefit from those approaches and are struggling to achieve sustained remission of depressive symptoms, representing an unmet need for novel agents with alternative mechanisms of action.11,12

The delayed, and in many cases poor, response to current antidepressants gives rise to the belief that more neurotransmitters are involved in the pathophysiology of depression than those suggested by the monoamine theory. Of them, glutamatergic system is the prominent one that accounts for the dysfunction and poor response.12 Growing evidence from animal and human studies has confirmed this system as a promising therapeutic target for MDD.13

Glutamate is an amino acid and the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain that has a key role in the modulation of synaptic plasticity and transmission.14 Furthermore, it is also the precursor of gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA), another major neurotransmitter responsible for most fast inhibitory transmissions.12,14 In the neocortex of human brain, 80% of neurons are spiny and excitatory and form 85% of all synapses, while the remaining 20% of neurons are smooth and inhibitory, forming 15% of the synapses.12 In this sense, the brain can be viewed as a sophisticated machine operating on mainly glutamatergic excitatory component, with the regulation of GABAergic inhibitory component as assistance.12 In other words, dysregulation of glutamatergic transmission or alterations in brain concentrations of glutamate may lead to the derangement of brain function.14 The presence of glutamatergic abnormalities has been discovered in the plasma, cerebrospinal fluid and brain tissue of individuals afflicted with mood disorders in multiple studies.12

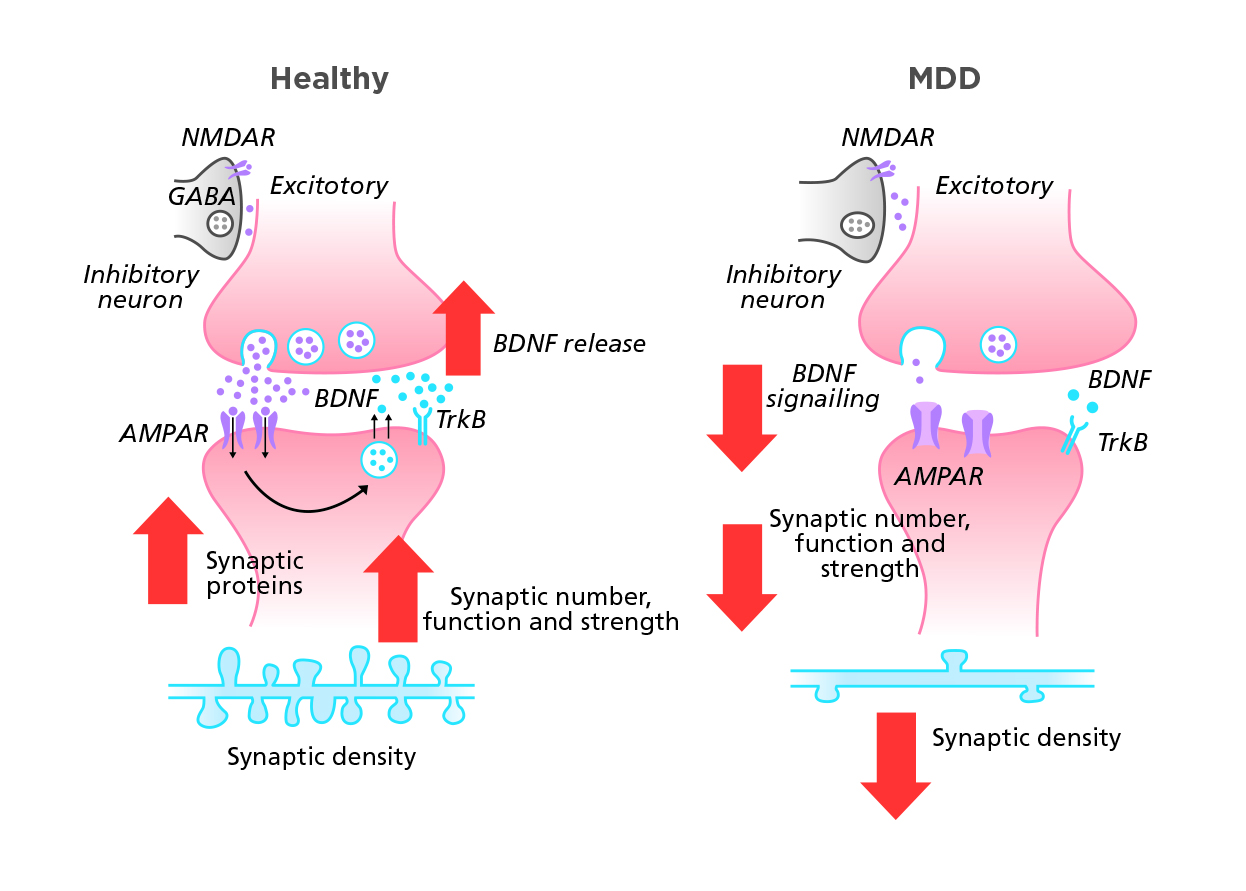

As a backbone to glutamate hypothesis, neuroplasticity is of notable significance in the brain’s adaptation to intrinsic and extrinsic signals. Therefore, how we handle information, ultimately translate into behaviors, relies heavily upon this neuroplasticity.15,16 In order to promote neuroplasticity, the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) which regulates the growth and survival of neurons in central nervous system should be enhanced.17,18 N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and a - amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) are the glutamate receptors widely distributed in the brain responsible for BDNF expression.16 Blockade of NMDA receptor and activation of AMPA receptor may promote BDNF expression, and binding of BDNF to its receptor tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrKB) activates downstream signaling pathways associated with synaptic plasticity, synapse formation, neuronal differentiation and survival.16,17 In short, glutamate is the primary system regulating neuroplasticity in the brain.

If the system is disrupted, atrophy of neurons and reduced synaptic connectivity may present and lead to disturbance in mood regulation and other associated functions as a result (Figure 1).16 Additionally, MDD patients have decreased serum BDNF levels.15 Thus reversing the deficit in BDNF through up-regulation very likely opens a window for potential depression treatment.16

Figure 1. Glutamate activity in different brains19

Adapted from Duman RS, et al. Nat Med. 2016.

Even supported by different hypothesis, typical antidepressants are still able to increase BDNF expression, but at a slower rate consistent with the time lag for genuine therapeutic actions.17 However there is no evidence on typical antidepressants causing activity dependent release of BDNF which is essential to rapid antidepressant activity.16 Delayed onset of therapeutic action implies the continuation of depression and its associated disability, and perhaps the potential risk of suicide for some patients.20 Besides, the quality of life of MDD patients will inevitably be limited by unceasing depressive episodes in terms of their ability to function socially and occupationally, thereby impairing the skills needed to work, to create and maintain relationships, and to function and be productive across multiple domains.21 Weeks of waiting for the potential symptom relief of typical antidepressants leave MDD patients vulnerable to those depression-related health and well-being issues.22

In the past decade, antidepressant research has come to a new era with a surge in literature publications on rapid-acting antidepressants, especially with ketamine being used as the prototype.22 The fast-paced efforts boosted the clinical discoveries in NMDA receptor antagonists that are believed to produce rapid antidepressant effects.22 For example, esketamine (the S-enantiomer of racemic ketamine) was approved for treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in adults in the United States in 2019.23 The approved esketamine with a novel mechanism of action improves brain plasticity via the stimulation of BDNF and activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), and its effects seem to sustain even after elimination of the drug from the body.23 In a phase 3 long-term trial, over 50% of esketamine-treated adult patients achieved remission at one year. 23 The Number Needed to Treat and Number Needed to Harm for esketamine were both less than 10 in a post-hoc study, indicating its efficacy probably outweighs the safety concern.23 Although the clinical performance of esketamine is quite appealing, post-marketing monitoring is still needed for better insight into its efficacy and safety in real-world settings.

The approval of rapid-acting esketamine starts a new chapter in depression treatment. Updates in treatment guidelines and changes in current landscape of medications are expected to see in the coming few years. With more understanding of the brain and pathophysiology of depression, it is believed that the treatment of depression will no longer be as challenging as before.

References

1. Our World In Data, the Global Change Data Lab. Mental Health. Available at https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health/. Accessed 26 Jan 2023. 2. Choi EPH, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 May 25;17(10):3740. 3. Frangou S, et al. Psychol Med. 2022 Jun 10:1-9. 4. Gautam S, et al. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017 Jan;59(Suppl 1):S34-S50. 5. Mayo Clinic. Depression (major depressive disorder) – Diagnosis & treatment. Available at https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20356013/. Accessed 26 Jan 2023. 6. Koenig AM, Thase ME. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009 Jul-Aug;119(7-8):478-86. 7. Delgado PL. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61 Suppl 6:7-11. 8. Boku S, et al. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018 Jan;72(1):3-12. 9. Chu A, Wadhwa R. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. [Updated 2022 May 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554406/. 10. Nguyen TTL, et al. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Jan 11;11:614048. 11. Al-Harbi KS. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:369-88. 12. Sanacora G, et al. Neuropharmacology. 2012 Jan;62(1):63-77. 13. Khoodoruth MAS, et al. Front Psychiatry. 2022 Apr 14;13:886918. 14. Onaolapo AY, Onaolapo OJ. Et al. World J Psychiatry. 2021 Jul 19;11(7):297-315. 15. Wainwright SR, Galea LA. Neural Plast. 2013;2013:805497. 16. Liu B, et al. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017 Sep 28;11:305. 17. Duman RS, et al. Eur J Neurosci. 2021 Jan;53(1):126-139. 18. Martin JL, Finsterwald C. Commun Integr Biol. 2011 Jan;4(1):14-6. 19. Duman RS, et al. Nat Med. 2016 Mar;22(3):238-49. 20. Tylee A, Walters P. BMJ. 2007 May 5;334(7600):911-2. 21. Machado-Vieira R, et al. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2010 Jan 6;3(1):19-41. 22. Witkin JM, et al. Adv Pharmacol. 2019;86:47-96. 23. Sapkota A, et al. Cureus. 2021 Aug 21;13(8):e17352.

The above content is for medical education purpose supported by Janssen, a division of Johnson & Johnson (HK) Ltd.