Specialist in Neurology

Put Up a Resistance to Drug-resistant Epilepsy

Patients with epileptic seizures that cannot be successfully controlled with antiepileptic drug (AED) therapy are considered to have drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE)1. DRE is a serious problem, and patients with DRE have increased risks of injuries, disability, psychosocial dysfunction and premature death2, 3. In this interview, Dr. Fong Ka Yeung Jason revealed some facts about DRE and shared his insights into how it is managed.

DRE Can Cause Significant Morbidity and Mortality

Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological diseases, affecting up to 60 million people globally4. In Hong Kong, although there are more than 20 approved antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), up to 30% of patients with epilepsy continue to have seizures despite treatment, according to Dr. Fong5. As defined by the International League against Epilepsy (ILAE), drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) is the failure of adequate trials of 2 AED schedules, whether as monotherapies or in combination, to achieve sustained seizure freedom, which could either be 3 times the prior interseizure interval or 1 year, whichever is longer. However, it must be stressed that the AED schedules are tolerated, and appropriately chosen and used6.

Frequent, severe uncontrolled seizures can cause injuries, disability and premature death3. According to Dr. Fong, DRE is also associated with not only neuropsychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety, depression, cognitive impairment and memory loss, but also psychosocial disabilities including poorer academic achievement and employment opportunities and impaired socialisation.

The Mechanism Underlying DRE Is Not Completely Understood

The pathogenesis underlying DRE is likely to be multifactorial and variable, and there are several hypotheses on how DRE develops2. As mentioned by Dr. Fong, an overexpression of multidrug efflux transporters in capillary endothelial cells that constitute the blood-brain barrier may restrict the access of AEDs to the seizure focus, thus causing drug resistance. As well as that, alteration in the cellular targets of AEDs and seizure-induced structural brain alterations have been proposed1.

On the other hand, identifying patients who are most at risk of developing DRE remains a challenge1. “Clinical predictors of drug resistance include the presence of a structural cause of epilepsy, such as hippocampal sclerosis, cortical dysplasia, and a high number of seizures prior to diagnosis and treatment, failure to respond to the first AED,” Dr. Fong pointed out.

A Personalised Treatment Plan Should Be Formulated

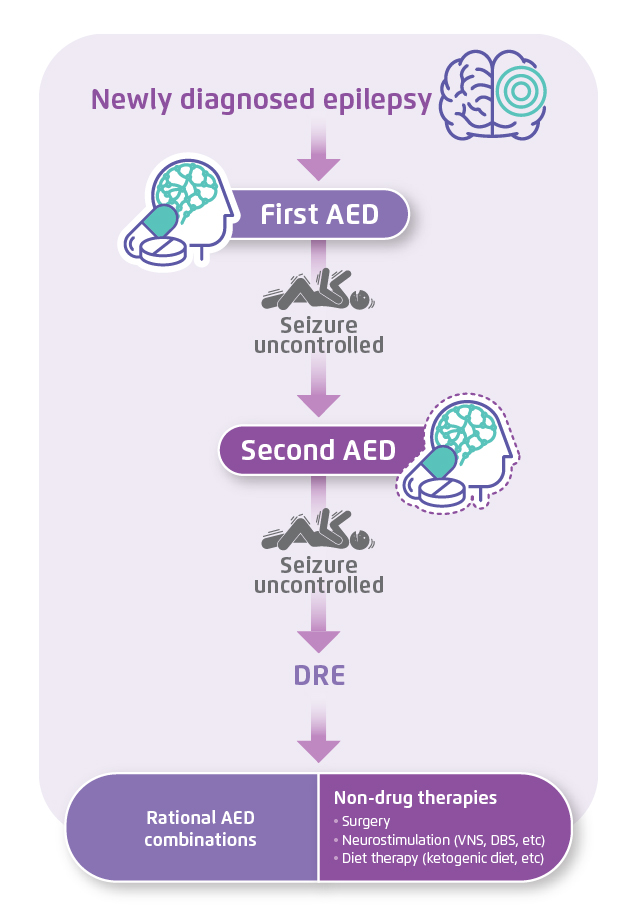

Treatment with AEDs is the standard of care for patients with DRE (Figure 1)1. According to Dr. Fong, it may be beneficial to choose an AED with a mechanism of action that differs from previous AEDs when considering adding a third AED. In fact, evidence supports the use of combination therapy with two or more AEDs with different mechanisms of action, as the drugs might offer synergistic efficacy without producing increased side effects1. However, use of a greater number of drugs should be avoided as it is unlikely for this strategy to produce useful seizure reduction2.

Figure 1. An algorithmic approach for the treatment of epilepsy1, 2. AED=antiepileptic drug. DBS=deep brain stimulation. DRE=drug-resistant epilepsy. VNS=vagus nerve stimulation.

Figure 1. An algorithmic approach for the treatment of epilepsy1, 2. AED=antiepileptic drug. DBS=deep brain stimulation. DRE=drug-resistant epilepsy. VNS=vagus nerve stimulation.

Apart from rational combination of AEDs, non-drug therapies such as epilepsy surgery, electrical stimulation and diet therapies can also be considered1, 2. As Dr. Fong said, surgery may be the only possible way to cure DRE and should be considered as soon as epilepsy is confirmed to be drug-resistant. The anterior temporal lobe resection in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy is the most common form of resective surgery in epilepsy1. Also, Dr. Fong stated that electrical stimulation therapy such as vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) and deep brain stimulation (DBS) could be considered when the patient is not a suitable surgical candidate1. VNS involves implanting a multiprogrammable pulse generator in the left chest, with the electrode connecting to the left vagus nerve in the neck, while DBS involves implanting electrodes into specific areas of the brain2, 7, 8. Besides, in Dr. Fong’s opinion, children with DRE can be treated with the ketogenic diet. The ketogenic diet is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate, moderate-protein diet that induces urinary ketosis and mimics starvation while preserving necessary caloric intake1, 9. “The main effects of the production of ketone bodies appear to be modulation of neurotransmitters, though the anticonvulsant mechanisms involved in the ketogenic diet are not entirely clear,” Dr. Fong commented. Furthermore, Dr. Fong stressed that treatment of DRE should not be restricted to the achievement of seizure freedom or reduction, however must include the management of various comorbid illnesses.

It Is Important to Distinguish DRE from Pseudoresistance

In Dr. Fong’s sight, uncontrolled epilepsy is not necessarily drug-resistant, and could potentially become controlled with an effective approach to pharmacotherapy. In fact, ruling out pseudoresistance, where seizures persist because the underlying disorder has not been adequately or appropriately treated, is important before AED treatment can be considered to have failed2. As Dr. Fong mentioned, incorrect diagnosis of the epilepsy condition, treatment with the wrong drug or the wrong dosage, poor compliance, and lifestyle issues such as sleep deprivation and alcohol abuse can contribute to pseudoresistance.

Dr. Fong used a clinical case to illustrate how pseudoresistance was tackled. The patient was a 39-year-old female director, who had been leading an extremely busy life. In the past year, she was brought to hospital after a second seizure attack and diagnosed with epilepsy. Levetiracetam was given twice daily, and she was advised to stay relaxed at work and get sufficient hours of sleep. She experienced the third epileptic seizure shortly afterwards, where during the attack, she injured her head. She confessed to Dr. Fong that she had skipped doses and split the pills in order to avoid side effects. After discussing medical treatment options, she decided to begin treatment with once-daily perampanel, and she has remained seizure-free ever since.

Reference

1. Dalic L and Cook MJ. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016;12:2605-2616. 2. Kwan P, et al. N Engl J Med 2011;365:919-926. 3. Krauss GL and Sperling MR. Neurol Clin Pract 2011;1:14-23. 4. Alkhidze M, et al. Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammation 2017;4:191-198. 5. Montouris G, et al. Epilepsy Res 2015;114:131-140. 6. Choi H, et al. Epilepsia 2016;57;1152–1160. 7. Sheng J, et al. Curr Neuropharmacol 2018;16:17-28. 8. Fridley J, et al. Neurosurg Focus 2012;32:E13. 9. de Lima PA, et al. Clinics 2014;69:699-705.