MBBS (HK), FRCR, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology), DMRT (UK)

Specialist in Clinical Oncology

President, Hong Kong Society of Uro-Oncology

Survival and Health-related

Quality of Life in Prostate Cancer:

What do We Expect in Darolutamide?

Prostate cancer (PCa) is currently the second most prevalent cancer and the 5th leading cause of cancer death in men globally, with an increasing incidence in East Asian countries1. Thanks to the advancement in therapeutics, the survival of patients with PCa has been significantly improved. Nonetheless, a substantial proportion of PCa survivors experienced poor health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and dissatisfaction with life over long run2. A recent survey on patients with non-metastatic castration-resistant PCa (nmCRPCa) indicated that patients were willing to sacrifice overall survival (OS) to reduce the risk and severity of treatment-related adverse events (AEs)3. This highlights the importance of HRQOL consideration in the management of advanced PCa. Notably, darolutamide, a structurally distinct androgen-receptor inhibitor (ARi) approved for the treatment of nmCRPCa, has been demonstrated to be effective in both improving survival and enhancing HRQOL.

Uncovering Psychological Burden of Advanced Prostate Cancer

Psychological distress is prevalent among patients with advanced PCa as compared to those with localised disease, and the morbidity adversely affects patients’ HRQOL4. Essentially, the responses of men to psychological distress is worsened by masculine beliefs, which prevent the patients from seeking medical support5. In recent years, validated screening tools evaluating distress level in patients with PCa have been developed and risk factors for higher distress have been identified. For instance, Chambers et al (2013) identified that younger age at diagnosis, lower education and income as well as advanced stage disease are risk factors for cancer-specific distress6.

Psychosocial Interventions for Patients with Prostate Cancer

Upon realising the psychosocial and psychosexual needs of the patients with PCa, interventions combining educational, cognitive behavioural, communication, and peer support components, followed by decision support and relaxation as well as supportive counselling were found to be effective in improving decision-related distress, mental health and HRQOL7. Nonetheless, patient’s specific life course, masculinity and cultural factors have to be considered in planning care and developing services.

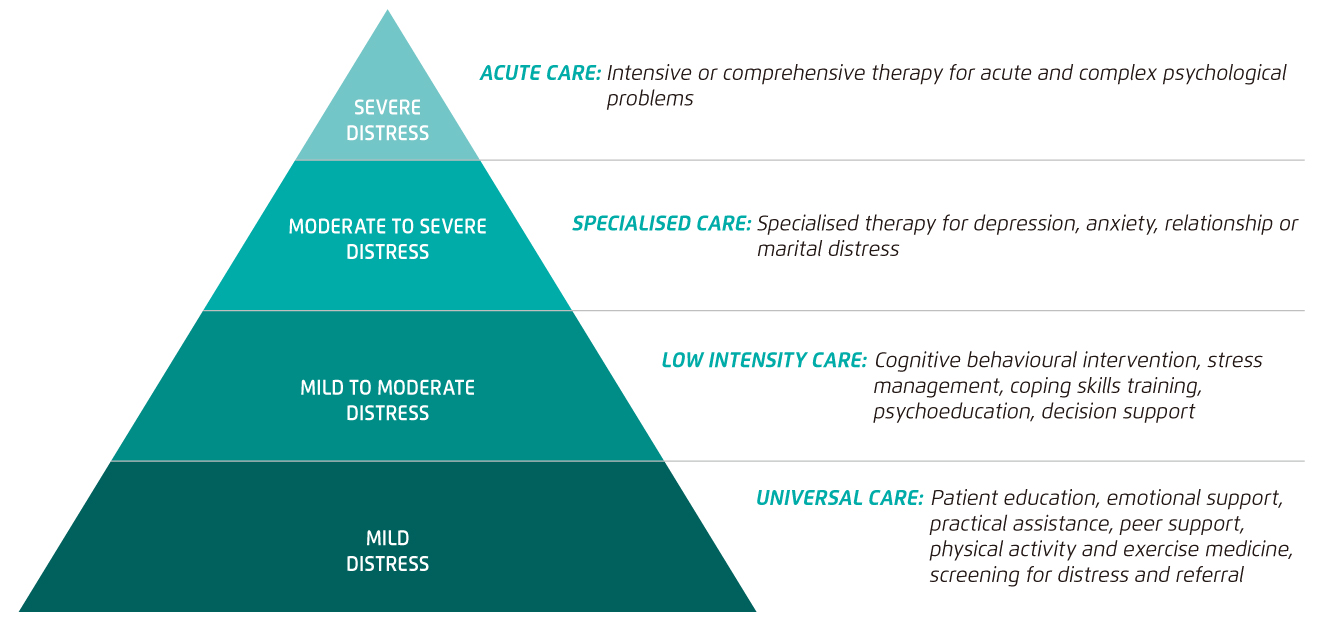

Practically, not all patients require a high level of psychosocial support. Thus, matching the level of patient need with the appropriate level of support is crucial for optimising the outcomes of psychosocial intervention for patients with PCa. Hence, Hutchison et al (2006) developed the tiered model of psychosocial care, which stratifies patients with PCa into 4 levels of distress ranging from mild to severe, to provide guidance on prescribing care corresponding to each distress level (Figure 1)8.

Figure 1. Tiered Model of Psychosocial Care after Prostate Cancer8

For the content of psychosocial intervention, opinions from leaders of clinical and community groups in PCa and survivorship care developed a framework of PCa survivorship essentials, which consists of 6 domains including, evidence-based survivorship interventions, vigilance, care coordination, shared management, health promotion and advocacy, and personal agency. In particular, personal agency is the core of the framework, which refers to supporting patients to develop skills to manage their treatment side effects and ongoing risk, monitor their treatment progress, effectively use healthcare services, and cope with the impact of PCa on their lives9. As a part of quality survivor care, self-management promotes healthy and preventive behaviours enabling patients with PCa to actively control their own health.

Clinical Benefit of Darolutamide in the Management of Advanced Prostate Cancer

In addition to psychological support, pharmacological intervention is undoubtedly an essential component in the management of advanced PCa. Particularly, patients with nmCRPCa are at risk for progression to metastatic disease. Hence, the major therapeutic goals for patients with nmCRPCa are to prolong survival, to delay the onset of cancer-related symptoms, and to minimise treatment-related adverse events10. To cope with the unmet needs in advanced PCa, new generation ARi have been developed. Darolutamide is one of the newly developed therapeutic agents proven to be effective in controlling nmCRPCa with a safety profile comparable with placebo and a minimal burden on patients’ HRQOL.

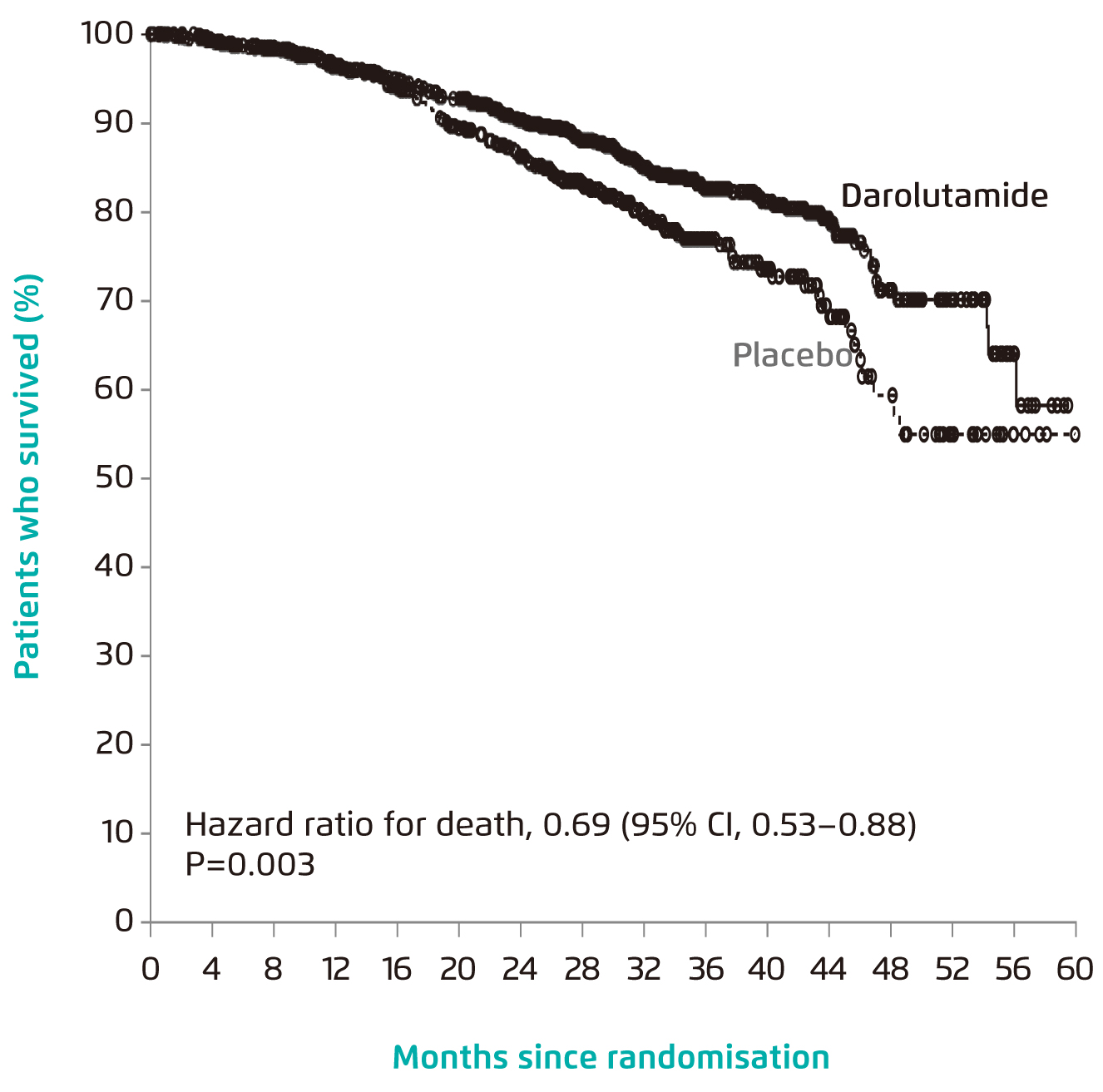

The clinical benefit of darolutamide has been demonstrated in the phase III ARAMIS trial involving 1,509 men with nmCRPCa. Upon a median follow-up of 29.0 months, the 3-year OS achieved with darolutamide treatment (n=955) was 83%, whereas that with placebo (n=554) was 77%. The risk of death was significantly reduced by 31% in patients received darolutamide (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.69, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.53-0.88, p=0.003, Figure 2). Also, darolutamide was associated with a significant benefit with respect to all other secondary end points, including the time to first symptomatic skeletal event and the time to first use of cytotoxic chemotherapy. Of importance, no significance in incidence of adverse events after commencement of treatment was observed between darolutamide and placebo10.

Figure 2. OS achieved by darolutamide10

Besides survival benefit, a sub-analysis of the ARAMIS trial further indicated that darolutamide treatment yielded a significant delay in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression (33.0 vs. 7.0 months, HR: 0.13, 95% CI: 0.11-0.16, p < 0.001) and cytotoxic chemotherapy (not reached vs. 38 months, HR: 0.43, 95% CI: 0.31-0.60, p < 0.001) as compared to placebo. The results also revealed that darolutamide maintained the HRQOL for patients with nmCRPCa that the onset of pain and disease-related urinary symptoms were delayed11.

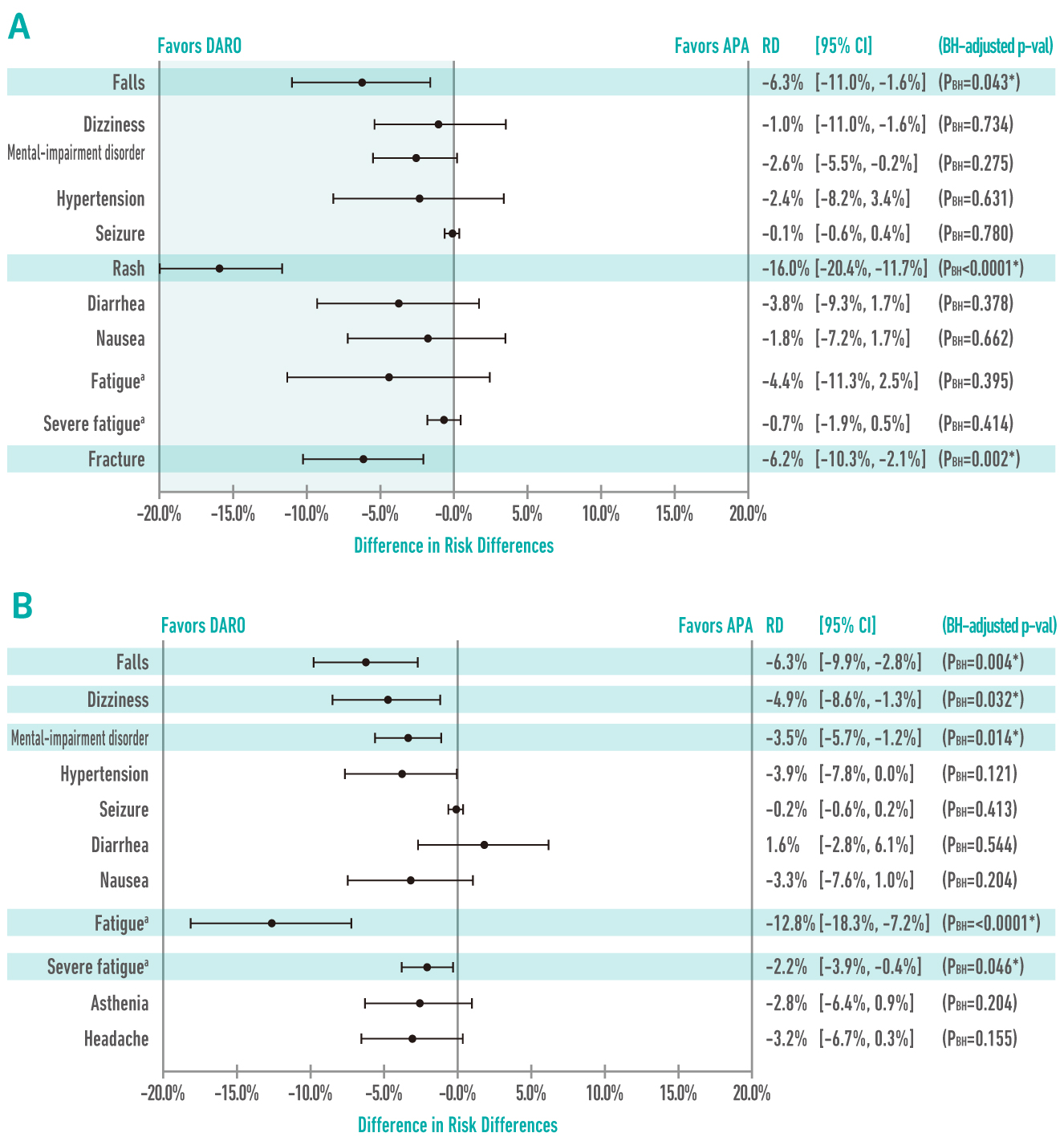

In a recent comparison on the efficacy and safety of darolutamide in patients with nmCRPCa versus apalutamide and enzalutamide, darolutamide was demonstrated to correlate with significantly lower rates of fall, fracture, and rash as compared with apalutamide (Figure 3A). In comparing with enzalutamide, the rates of fall, dizziness, mental impairment, fatigue, and severe fatigue were statistically significantly lower in favour of darolutamide (Figure 3B)12. While treatment-related AEs are a major predictor of HRQOL13, the preferable safety profile of darolutamide demonstrated in former trials thus implies that the treatment would better maintain the HRQOL for patients with nmCRPCa.

Figure 3.

Comparisons on risk differences (RD) of treatment-related AEs among ARi12,

(A) darolutamide (DARO) vs. apalutamide (APA); (B) darolutamide vs. enzalutamide (ENZA);

BH: Benjamini-Hochberg

Comprehensive Management of Prostate Cancer

The health burden of PCa is substantial with an increasing incidence in East Asian countries. Although the survival of patients with PCa has been improved significantly in recent years, optimising HRQOL is still challenging practically. The comprehensive management of PCa, especially for those with advanced disease, involves not only pharmaceutical intervention but also psychosocial supports provided by a multidisciplinary team and self-management by the patients. In view of pharmacological treatment, the impact of treatment-related AEs is a core factor to be considered. Former clinical data suggested that darolutamide is effective in delaying disease progression and subsequent treatment for advanced PCa and, essentially, maintaining HRQOL without increasing incidence of key AEs.

References

1. Bray et al. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68: 394-424. 2. Ralph et al. Psychooncology 2020; 29: 444-9. 3. Srinivas et al. Cancer Med 2020; 9: 6586-96. 4. Chambers et al. Nat Rev Urol 2018; 15: 733-4. 5. Occhipinti et al. Am J Mens Health 2019; 13: 1557988319859706. 6. Chambers et al. Psychooncology 2014; 23: 195-203. 7. Chambers et al. Psychooncology 2017; 26: 873-913. 8. Hutchison et al. Psychooncology 2006; 15: 541-6. 9. Dunn et al. BJU Int 2020; : bju.15159. 10. Fizazi et al. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 1040-9. 11. Pang et al. Ann Oncol 2019; 30: ix69. 12. Halabi et al. J Urol 2021; : 101097JU0000000000001767. 13. Tonyali et al. Curr. Urol.2017; 10: 169-73.