Non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has entered a new era of precision oncology, where increasingly rare genomic targets—such as BRAF V600E, HER2 (ERBB2) activating mutations, ROS1 fusions, KRAS G12C/G12D, MET exon 14 skipping, and EGFR exon 20 insertions—are reshaping clinical outcomes for subsets of patients historically underserved by standard therapies.1 Drawing on 2025 updates from multi‑center trials and regulatory decisions, this article synthesizes the latest efficacy, safety, and translational insights across these targets, highlights milestones such as near 4‑year median overall survival (OS) in frontline BRAF inhibition, head‑to‑head phase III trajectories in HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) development, robust intracranial control with lorlatinib after first‑line ROS1 TKI failure, and emerging central nervous system (CNS) activity with novel KRAS inhibitors. We further summarize progress for KRAS G12D, MET exon 14, and EGFR exon 20 insertions and articulate practical implications for diagnostic standardization, treatment sequencing, ctDNA‑guided response assessment, and equitable access. Finally, we outline future priorities—combination strategies, resistance profiling, trial designs for earlier disease stages, and biomarker refinement—to accelerate benefit across the NSCLC rare‑target landscape.

Lung cancer remains among the leading causes of cancer morbidity and mortality worldwide, with NSCLC constituting the majority of cases. As molecular subtyping and targeted therapeutics advance, the umbrella term rare targets increasingly denotes a clinically significant aggregation of patients who harbor low‑frequency but actionable alterations. In 2025, several pivotal analyses and regulatory actions have converged to redefine standards of care for NSCLC patients with rare genomic drivers, spanning BRAF V600E, HER2 TKD mutations, ROS1 fusions, KRAS G12C/G12D, MET exon 14 skipping, and EGFR exon 20 insertions.

The IFCT‑2003 ALBATROS study addressed an unmet need: what to do after first‑line ROS1 TKI failure (commonly crizotinib). In 54 patients (median age 63; 57.4% with baseline brain metastases; 94.4% previously treated with crizotinib), lorlatinib achieved investigator‑assessed objective response rate (ORR) 30% and disease control rate (DCR) 84%, Blinded Independent Central Review (BICR) ORR 34% and DCR 74%. Median duration of response (DoR) was 20.4 months, median progression-free survival (PFS) 7.4 months, and median OS 42.3 months, reflecting durable systemic control.2

Crucially, intracranial efficacy was striking: among 13 patients with measurable brain metastases at baseline, intracranial ORR reached 92.3% and intracranial DCR 100%—a hallmark of third‑generation TKI performance against CNS disease. Safety was manageable despite ≥grade 3 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in 45.3%; permanent discontinuation was rare (~1%), and dose reductions (30%) addressed hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and peripheral edema.2

In summary, after earlier‑line ROS1 TKI failure, lorlatinib delivers substantial intracranial control and prolonged response duration, reinforcing a continuum‑of‑care model for ROS1‑positive NSCLC with attention to lipid management and dose modifications.2

KRAS G12C occurs in roughly 12–14% of NSCLC and carries a high burden of brain metastases (approximately 25–42%), historically portending poor outcomes. The LOXO‑RAS‑20001 cohort focused on olomorasib, a novel G12C inhibitor, in patients with active, untreated brain metastases. Among 21 patients (median age 65; 52% prior cranial radiotherapy; 67% prior platinum plus immunotherapy), intracranial ORR was 43% (9/21, including five complete responses), and DCR was 86%; responders had DoR >6 months at analysis.3

Safety was favorable: diarrhea (28%, ≥grade 3 ~1%), nausea (12%), fatigue (9%); dose reductions (7.5%) and permanent discontinuations (1.0%) were infrequent. Global registration trials—SUNRAY‑01 (NCT06119581) and SUNRAY‑02 (NCT06890598)—are exploring frontline combinations with pembrolizumab in advanced and earlier‑stage NSCLC.3

As a whole, demonstrated CNS activity in untreated brain metastases represents a meaningful advance for KRAS G12C inhibitors. The evolving competitive edge will hinge on chemotherapy‑free regimens (e.g., immunotherapy combinations) and on systematically overcoming resistance.3

Zongertinib, designed to irreversibly inhibit HER2 while sparing wild‑type EGFR, demonstrated compelling first‑line activity in Beamion LUNG‑1 cohort 2. Among 74 advanced HER2‑mutant NSCLC patients (median age 67; 50% female; 30% with baseline brain metastases), the BICR‑assessed ORR was 77% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 66–85), with 8% complete responses and 69% partial responses; DCR reached 96%. Six‑month DoR and PFS rates were 80% and 79%, respectively; median treatment duration was 10.3 months, with 47% of responders still on therapy at cutoff.4

Safety was favorable: TRAEs in 91%, grade 3 in 18%, with predominant events of diarrhea, rash, transaminase elevations, taste disturbance, and nausea; no grade 4–5 events were observed.4 In 2025, the FDA granted accelerated approval for zongertinib (August 8) in HER2 TKD‑mutant non‑squamous NSCLC,5 and China’s National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) issued conditional approval (August 29) for previously treated locally advanced/metastatic disease.6 A head‑to‑head phase III Beamion LUNG‑2 (NCT06151574) is enrolling to compare zongertinib versus standard chemotherapy in the first line.

SOHO‑01 evaluated sevabertinib across three cohorts: D (post‑line, HER2‑targeting naïve; n=81), E (post‑line after HER2‑ADC; n=55), and F (first‑line; n=73). BICR‑assessed ORR values were 64% (D), 38% (E), and 71% (F); median PFS was 8.3 months (D), 5.5 months (E), and not reached (F). In cohort D, patients with baseline brain metastases achieved ORR 61%, comparable to those without (65%), and only 6% of patients without baseline brain metastases experienced intracranial progression—underscoring CNS penetration.7

Biomarker granularity matters: HER2 TKD mutation carriers had superior outcomes; notably, Y772_A775dupYVMA patients reached ORR 78% and median PFS 12.2 months, outperforming other TKD variants (median PFS ~7.0 months). Dominant TRAE was diarrhea (any grade up to 87%; grade 3 ranging 5–23% across cohorts), with no grade 4 events, no ILD/pneumonitis, and no discontinuations attributed to diarrhea.7

Taken together, with zongertinib and sevabertinib demonstrating high response rates and encouraging CNS control, HER2‑mutant NSCLC is shifting from a therapeutic desert to a landscape of multiple first‑line options. Next steps involve defining optimal patient selection by mutation subtype, and exploring rational sequences or combinations with antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs).4,7

PHAROS, a phase II single‑arm study, evaluated encorafenib (BRAF inhibitor) plus binimetinib (MEK inhibitor) in advanced BRAF V600E‑mutant NSCLC, enrolling distinct cohorts of treatment‑naïve (n=59) and previously treated (n=39) patients. The goal was descriptive assessment of efficacy and safety across first‑line and post‑line settings.8

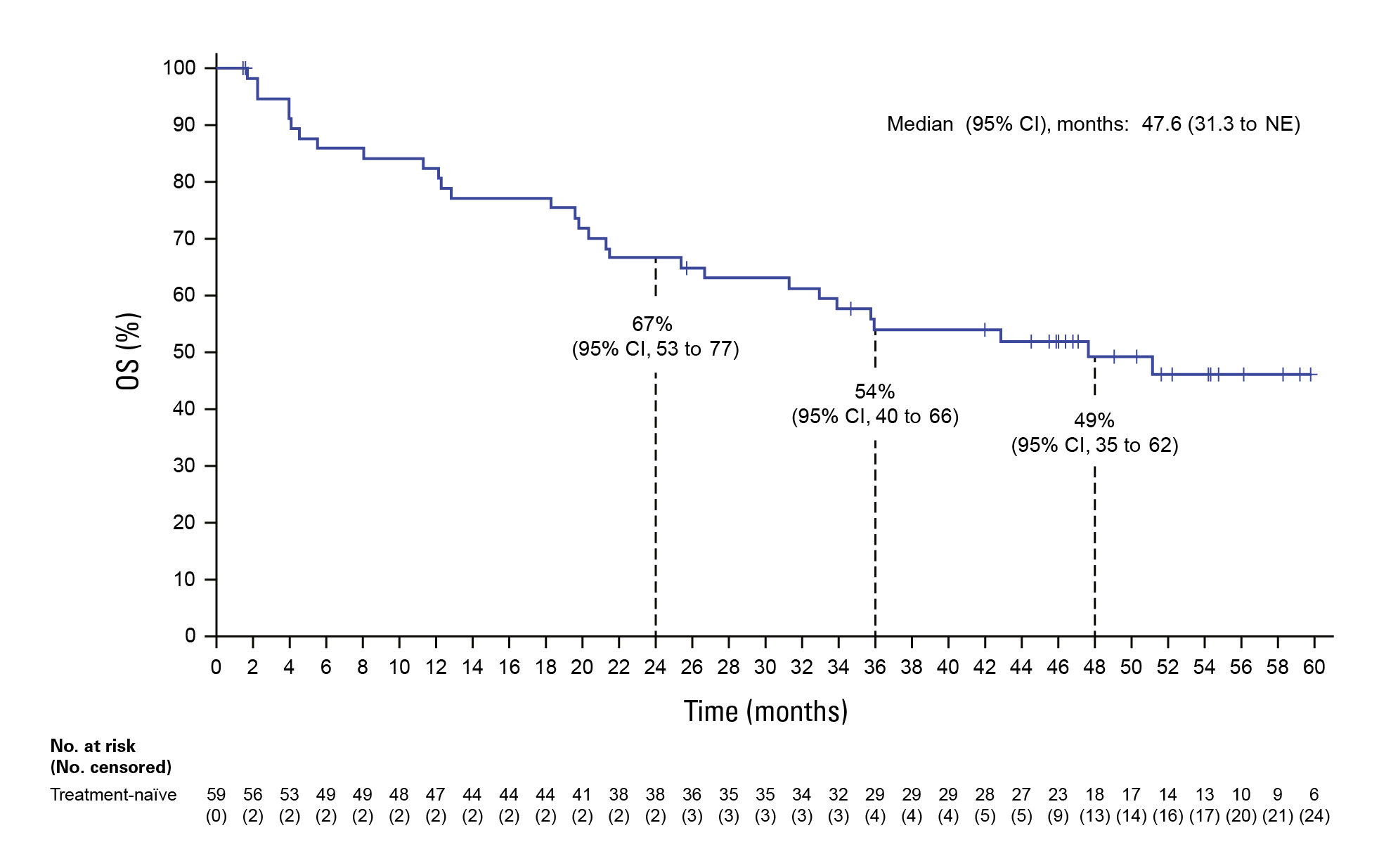

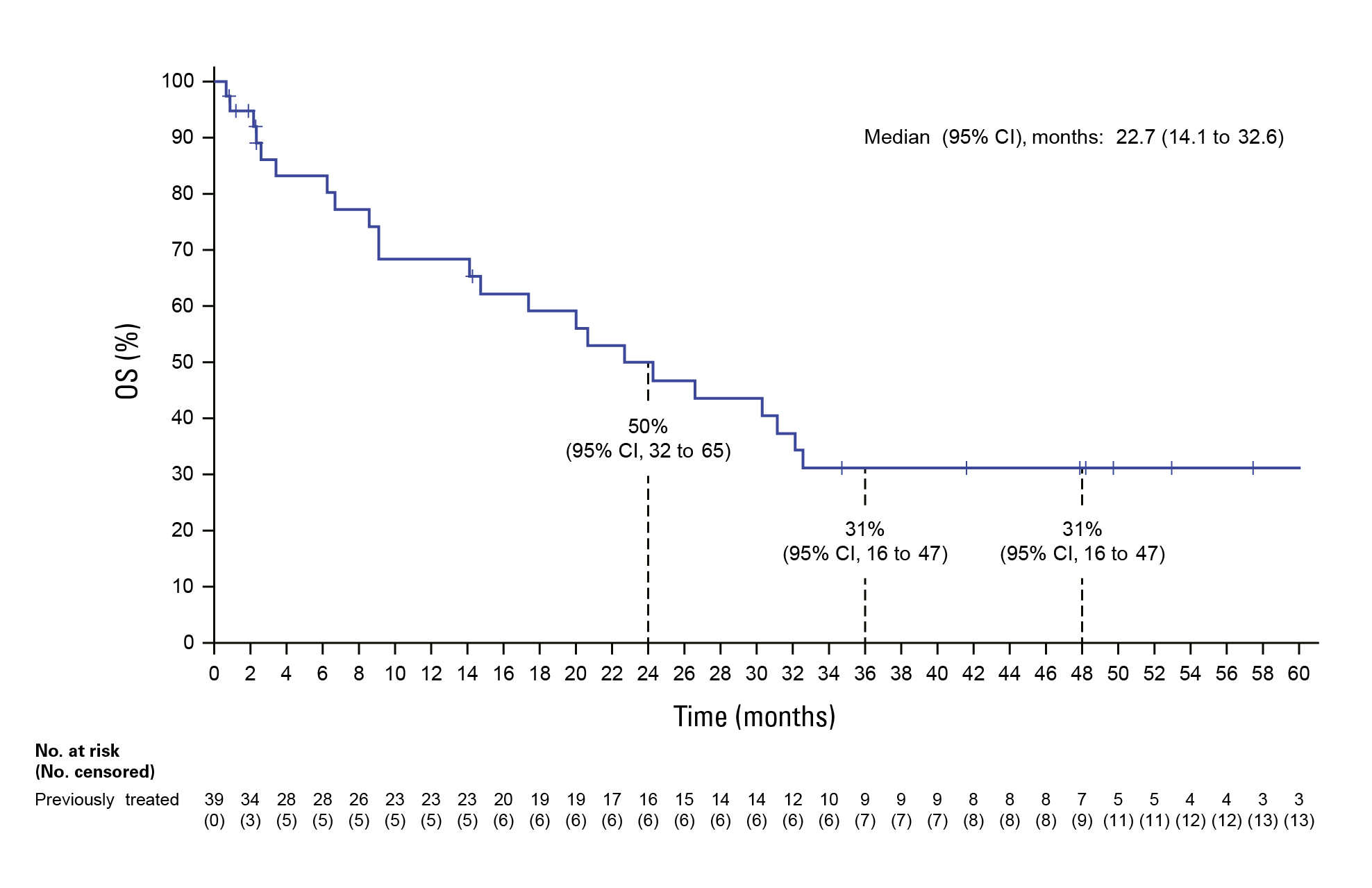

By the 2025 analysis cut (March 14, 2025), with median follow‑up approaching four years (PFS follow‑up ~38.8 months; OS follow‑up ~52.3 months), the regimen achieved median OS of 47.6 months and a 4‑year OS rate of 49% in the frontline cohort; in previously treated patients, median OS was 22.7 months with a 31% 4‑year OS rate. Median PFS reached 30.4 months (first‑line) and 9.3 months (post‑line)—the longest survival signals reported to date for this target in NSCLC (Figure 1,2). Objective responses were robust: ORR 75% and median DoR 40 months in first‑line; ORR 49% post‑line. These results informed regulatory approval and guideline endorsement of encorafenib + binimetinib as a frontline standard for metastatic BRAF V600E NSCLC.8

Figure 1. OS in treatment-naive patients8

Figure 2. OS in previously treated patients8

Treatment‑related adverse events (TRAEs) were manageable; common events included nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, and vomiting, with no emergent safety signals. Notably, 58% of frontline and 26% of post‑line patients received subsequent systemic therapy after discontinuation, frequently immune checkpoint–based regimens or re‑challenge with BRAF±MEK inhibitors—informing real‑world sequencing strategies.8

In summary, dual BRAF/MEK inhibition sets a high durability benchmark, motivating research into resistance mechanisms and extending dual‑targeted therapy into perioperative settings (neoadjuvant/adjuvant) for broader patient benefit.

In pretreated NSCLC, GFH375 showed promising activity: ORR 57.7% and DCR 88.5%, with enhanced outcomes at 600 mg QD (ORR 68.8%; DCR 93.8%)—a notable step against a historically “undruggable” mutation.9

Dynamic ctDNA monitoring offers prognostic value. At week 4, patients achieving ctDNA clearance of MET ex14 demonstrated ORR 80%; conversely, longitudinal ctDNA positivity (≥2 positive time points) predicted early progression—supporting ctDNA as a practical tool for early on‑treatment assessment.10

For patients previously treated with amivantamab, zipalertinib achieved ORR 30% and DCR 96.7%; median DoR 14.7 months and median PFS 7.6 months, with 12‑month OS 66.1%, signaling utility in subsequent lines.11

As a whole, the pipeline for traditionally difficult targets is diversifying, while ctDNA‑based response kinetics are sharpening the precision of therapeutic evaluation.

Rare‑target identification depends on comprehensive molecular profiling. Ensuring broad NGS panels that cover BRAF, HER2 TKD variants, ROS1 fusions, KRAS G12C/G12D, MET exon 14 skipping, and EGFR exon 20 insertions is critical to unlock targeted options early—particularly in community settings where under‑testing can preclude timely therapy.12

Regulatory approvals (e.g., zongertinib in the US and China) expand availability, but cost, reimbursement, and geographic disparities remain barriers. Strategic deployment of patient assistance programs, real‑world evidence to support health‑technology assessments, and regional guidelines can improve uptake.

Data from PHAROS, ALBATROS, and HER2 programs suggest viable post‑progression strategies: immune checkpoint inhibitors or targeted re‑challenge after BRAF/MEK; lorlatinib after ROS1 TKI failure; and potential HER2 TKI–ADC sequences. Formal comparative trials and prospective sequencing studies, including CNS‑focused endpoints, are needed.

Early ctDNA dynamics (e.g., MET ex14 clearance at week 4) can inform on‑treatment decisions—supporting treatment continuation or adjustment. Integration into routine care requires harmonized assays, defined time points, and education across care teams.13

To operationalize these gains, institutions can formalize a “rare‑target pathway”:14,15

Despite promising results, several gaps remain:

The 2025 landscape for rare targets in NSCLC reflects tangible clinical momentum: BRAF V600E dual inhibition achieves near 4‑year median survival in the frontline; HER2 TKIs (zongertinib, sevabertinib) deliver high response rates with manageable toxicity and emerging CNS activity; lorlatinib offers a compelling post‑ROS1 TKI option with exceptional intracranial control; and KRAS G12C inhibitors like olomorasib demonstrate meaningful CNS responses in untreated brain metastases. Progress across KRAS G12D, MET exon 14, and EGFR exon 20 insertions further broadens the therapeutic armamentarium, while ctDNA dynamics begin to inform early treatment decisions.

Translating these gains into everyday practice demands standardized testing, equitable access, thoughtful sequencing, and integration of CNS and ctDNA‑guided management. Looking ahead, priorities include rigorous randomized trials, earlier‑stage applications, resistance‑directed strategies, and variant‑specific biomarker refinement. If pursued systematically, these directions can reshape outcomes for patients whose tumor biology previously offered few options—cementing rare‑target precision therapy as a durable pillar of NSCLC care.

References

1. MMina SA, et al. Cancers. 2025; 17(3): 353. 2. Duruisseaux M, et al. Efficacy of lorlatinib after failure of a first-line ROS1 TKI in patients with advanced ROS1-positive NSCLC: IFCT-2003 ALBATROS trial. 2025 ESMO. Abstract 5524. 3. Cassier P, et al. Intracranial efficacy of Olomorasib in patients with KRAS G12C-mutant NSCLC and active, untreated brain metastases. 2025 ESMO. Abstract 1846MO. 4. Popat S, et al. Zongertinib as first-line treatment in patients with advanced HER2-mutant NSCLC: Beamion LUNG-1. 2025 ESMO. LBA74. 5. Lung Cancer Research Foundation. Zongertinib for HER2+ lung cancer. 28 August 2025. Available from: https://www.lungcancerresearchfoundation.org/sms250827/. [Accessed 25 November 2025]. 6. Pharmaceutical Technology. China’s NMPA conditionally approves Boehringer’s tablets for NSCLC. 2 September 2025. Available from: https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/news/boehringer-nsclc-nmpa/. [Accessed 25 November 2025]. 7. Le X, et al. Sevabertinib in advanced HER2-mutant non–small-cell lung cancer: results from the SOHO-01 study. 2025 ESMO. LBA75. 8. Johnson ML, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2025 Oct 19:JCO2502023. doi: 10.1200/JCO-25-02023. Online ahead of print. 9. Yoshinari T, et al. Commun Chem. 2025;8(1):254. 10. Mazieres J, et al. Clin Lung Cancer. 2023;24(6):483-97. 11. Dorta-Suárez M, et al. Cancer Treat Rev. 2024;124:102671. 12. Liu X-D, et al. Heliyon . 2024;10(6):e27591. 13. Xia Y, et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2025;81:103099. 14. D’Aiello A, et al. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(3):844. 15. Kokkotou E, et al. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16(7):1414.