Specialist in Psychiatry

Anxiety disorders are one of the most prevalent psychiatric disorders, up to 30% of the population are reported to be affected by an anxiety disorder during their lifetime. While anxiety disorders are associated with a significant disease burden and economic costs, substantial underdiagnosis and undertreatment of the disorders have been demonstrated in clinical settings1. In the current Feature Story, Dr. Chong King Yee was invited to share her experiences in managing anxiety disorders and discuss specific clinical issues in psychiatric disorders, including the feasibility of anxiety screening and the role of artificial intelligence (AI).

Anxiety is a normal reaction to stress, and an appropriate level of anxiety is essential for us to face dangers. However, medical attention will be required when fears and anxieties are disproportionate to a threat, are severe and enduring, or disrupt normal functioning. In contrast to normal anxious feelings, the core features of anxiety disorders include excessive fear and anxiety or avoidance of perceived threats that are persistent and impairing. Anxiety disorders involve dysfunction in brain circuits that respond to danger2.

There are various types of specific anxiety disorders sharing characteristics of excessive fear and worry along with somatic symptoms. Accordingly, Dr. Chong noted that generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PD), specific phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and mixed anxiety–depressive disorder (MADD) are anxiety disorders commonly observed in Hong Kong.

Regarding the assessment of patients reporting anxiety symptoms, Dr. Chong highlighted the importance of a comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s medical history to appreciate if there are any physiological causes. Attention should also be paid to the duration and severity of symptoms. “While anxiety disorders adversely affect patients’ daily life, including their study, career, and social life, their impacts in these aspects have to be evaluated as well.” Dr. Chong emphasised.

Dr. Chong outlined that people with a family history of mood disorders would have a higher risk of anxiety disorders. Additionally, she noted that there are environmental factors contributing to the increased risk of anxiety disorders, such as a stressful working condition, tension among family members, and childhood adversity.

Of note, an analysis of a nationally representative sample of the adult population of the United States (U.S.) by Blanco et al. (2014) reported that low self-esteem, family history of depression, female sex, childhood sexual abuse, White race, years of education, number of traumatic experiences, and disturbed family environment increased the risk of anxiety disorders3.

Interestingly, Dr. Chong addressed that there are emerging clinical data suggesting that inadequate sleep and overtime work are associated with an increased risk of anxiety disorders. In this regard, the analysis of German Health Survey data by Ramsawh et al. (2009) indicated that most anxiety disorders were significantly associated with reduced sleep quality, with the strongest associations observed in social phobia and GAD. Essentially, the study concluded that individuals with anxiety disorders and poor sleep experience significantly worse mental health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and increased disability relative to those with anxiety disorders alone4.

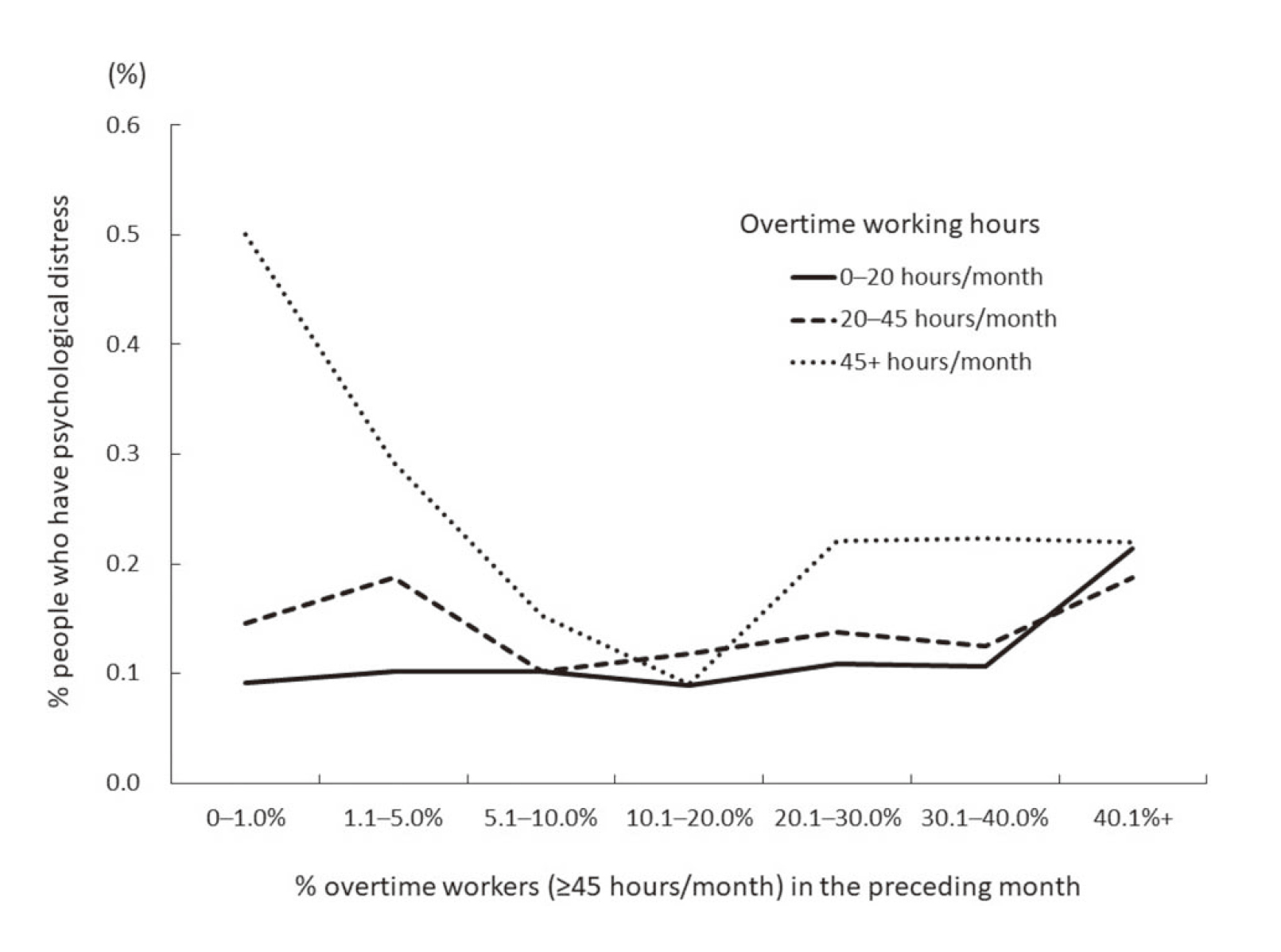

Besides, a study of 7,786 Japanese workers by Ishida et al. (2020) demonstrated the association between overtime-working environment (OWE) and individual psychological distress that a 10% increase in the OWE was associated with a 16% higher risk of individual psychological distress (Figure 1)5.

Figure 1. The association between the percentage of overtime work and the percentage of workers with psychological distress5

From the brief highlights above, the risk factors for anxiety disorders are highly diversified and can occur at different stages within a person’s lifetime.

Anxiety disorders place a significant humanistic burden on affected individuals. Compared to non-anxious individuals, those with anxiety disorders are more likely to have reduced psychosocial functioning and life satisfaction. In addition, the socioeconomic burden of anxiety disorders is substantial.

Dr. Chong outlined that there are 3 major categories of anxiety symptoms. Firstly, most patients develop emotional symptoms, which are expressed as excessive fear, worry, and/or anxiety. Dr. Chong recommended that an investigation on the factors triggering anxiety would help in understanding the aetiology, though there can be no specific triggering factor for certain GAD cases.

Besides, patients with anxiety may exhibit cognitive symptoms such as catastrophic thoughts. Dr. Chong noted that these patients typically exaggerate the impacts of matters, no matter how minor and rare they are. “Many of them frequently say, “Oh my god, it’s bad!” she described. The way they interpret issues is different from non-anxious people. For instance, if they travel by bus, they may worry if they will be killed in a traffic accident caught by the bus. Another common symptom is worry about suffering from diseases. These patients would undergo many medical tests due to extremely minor symptoms.

Moreover, patients with anxiety disorders can exhibit somatic symptoms, including increased heart rate, headache, nausea, vomiting, and other GI symptoms, upon minor triggering. Dr. Chong remarked that some cases of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are associated with anxiety disorders, whereas resolving anxiety leads to a relief of GI symptoms. Notably, a previous meta-analysis by Sibelli et al. (2016) confirmed that self-reported anxiety and depression provide a twofold risk for IBS onset6.

Apart from physiological symptoms, anxiety disorders also significantly impact the socioeconomic status and overall well-being of the patients. Dr. Chong said that some patients with anxiety disorders may have extremely high standards and expectations for all matters in daily life, not only for themselves but also for other people, such as colleagues, classmates, and family members. Attempting to meet such unrealistic standards would create stress for other people, thus leading to interpersonal conflicts.

Besides, patients with anxiety disorders may have difficulty coping with the stress associated with uncertainties in the working environment. Hence, they would reject career or learning opportunities in order to avoid potential uncertainties. Furthermore, anxiety symptoms potentially increase absenteeism. Dr. Chong addressed that some students with the disorder would refuse to attend classes since they cannot cope with the stress in class. On the other hand, anxiety-related somatic symptoms, such as fibromyalgia, affect the leisure life of patients since physical discomfort prevents them from engaging in physical exercises and social events.

Provided the high prevalence of anxiety disorders as well as the associated significant disease burden and economic costs, routine anxiety screening theoretically could increase the likelihood that patients receive timely treatment, hence potentially saving years of distress and reducing economic burden. Nonetheless, Dr. Chong commented that routine screening for anxiety and other mood disorders would be practically difficult. “Patients with mood disorders may not participate in screening. Those people who have screening result positive, may not accept any further psychiatric assessment, referral or treatment,” she explained.

Dr. Chong’s comments aligned with the findings of a recent meta-analysis of 59 clinical studies by O’Connor et al. (2023) that no clinical benefit in anxiety and depression outcomes, global quality of life, and functioning was yielded by anxiety screening programs7. Instead of screening, Dr. Chong suggested identifying anxiety disorder cases based on clinical assessment of symptoms with high index of suspicion. “If an anxious patient complains about persistent somatic symptoms, such as palpitations, insomnia, aches and pains, gastrointestinal (GI) problems, referral to mental health professionals is recommended if symptoms persist despite usual treatment,” she advised.

Although timely identification of patients with anxiety disorders by screening may not be feasible, effective treatments for the disorders do exist. These treatments can be classified into pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Given anxiety disorders are related to the imbalance of various neurotransmitters in the brain, primarily norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine, most medications against anxiety disorders act by regulating the secretion and function of these neurotransmitters8. Remarkably, Dr. Chong noted that tranquillisers are commonly prescribed for insomnia. However, she emphasised that normal sleeping pattern will resume when anxiety symptoms improve. Thus, long-term use of tranquilliser is usually not required.

In managing anxiety disorders, Dr. Chong reminded that the symptoms exhibited by each patient are specific. Therefore, pharmacotherapy should be tailored for each patient, considering symptoms and side effect profiles. She mentioned that different patients may respond to the same medication differently. “The medication that works well in this patient may not be tolerated by the other patients,” per Dr. Chong. Given there are many treatment options currently available for the long-term control of anxiety disorders, switching treatment can be considered if necessary.

Evidence-based psychotherapies, as pharmacotherapies, are considered first-line treatments for anxiety disorders. Psychotherapies range from low-intensity interventions incorporating self-help approaches, such as bibliotherapy, to high-intensity therapies with a specialised therapist according to disorder severity2, whereas cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is the most frequently applied psychotherapy.

CBT is a short-term therapy derived from principles of behavioural and cognitive psychology. A key CBT component for most forms of anxiety disorder involves exposure to the feared stimuli, either in vivo or imaginal2. Practically, Dr. Chong outlined that CBT involves communication with the patients to figure out if there are any cognitive distortions triggering anxiety and providing guidance on coping with stress.

In particular, Dr. Chong introduced the application of mindfulness training in anxiety disorders, which teaches patients meditation techniques that increase awareness of present-moment experiences, including thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations, with a gentle and accepting attitude towards oneself. In the randomised controlled trial (RCT) involving 93 patients with GAD by Hoge et al. (2013), 8-week mindfulness training was shown to reduce anxiety symptoms significantly and was associated with a greater increase in positive self-statements9.

Regarding the choice of behavioural strategies in psychotherapy, Dr. Chong emphasised that we need to select the appropriate option according to the patient’s interests, lifestyle, and personal needs.

Even though numerous clinical data advocating the benefits of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, under-diagnosis and under-treatment are clinical challenges in managing patients with anxiety disorders, resulting in a low remission rate. Dr. Chong stated that some patients would deny suffering from anxiety symptoms and refuse to seek help from healthcare professionals, whereas others may not be aware the symptoms are related to anxiety. Thus, Dr. Chong highlighted the importance of detailed explanation for somatic symptoms so as to enhance patient’s understanding.

Once anxiety disorder is diagnosed, ensuring patient adherence to treatment is the next challenge. Of note, the long duration of treatment effect onset would discourage patients. Dr. Chong opined that pharmacotherapies for anxiety disorders may take several weeks to generate noticeable benefits. Accordingly, patients may consider the treatment ineffective and not comply with it. Even worse, they might lose their trust towards physicians and give up treatment. Therefore, thorough communication with patients before treatment on the expected progress is essential for managing their expectations and enhancing their compliance.

Even if the treatment is effective, Dr. Chong said some patients would discontinue treatment due to misunderstanding about the treatment endpoint. “Patients might reduce or even discontinue treatment upon symptom improvement,” she addressed. Essentially, Dr. Chong highlighted symptom improvement does not necessarily indicate a treatment endpoint. She emphasised that treatment completion should be considered as the state in which all symptoms are eliminated, and the patient’s overall condition becomes comparable to that before the disease.

In recent years, notable progress has been made in developing and utilising AI-based applications and environments to improve the precision and sensitivity of diagnosis and treatment in various medical specialties. In psychiatry, there are investigations applying AI in preliminary assessment and identifying patterns that may suggest symptoms of anxiety, depression, or other mental health issues, analysing patient's speech for mood and stress assessment, behavioural coaching, etc10.

Nonetheless, Dr. Chong commented that solid evidence supporting the use of AI in psychiatry is still limited. She remarked that anxiety often originated from uncertainty and perceived lack of support. Instead of using AI, having emotional support from family and friends, as well as the caring attitude of healthcare professionals, are essential for relieving anxiety.

Apart from advanced technology, Dr. Chong highlighted the importance of continuous professional development among healthcare professionals. The awareness of the linkage between the brain and other organs needs to be enhanced, especially in handling difficult-to-treat cases with unclear aetiologies. Interdisciplinary communication and continuous medical education (CME) are helpful means of maintaining up-to-date medical knowledge.

To conclude, Dr. Chong opined that psychiatric disorders are curable with good compliance with treatment. As the symptoms and responses to treatments are unique for each individual, patients should have their doctor well informed about their condition. “Promising treatment outcomes rely on the collaboration between patients and healthcare professionals”, she expressed.

References

1. Bandelow et al. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2015; 17: 327. 2. Penninx et al. Lancet 2021; 397: 914. 3. Blanco et al. Depress Anxiety 2014; 31: 756–64. 4. Ramsawh et al. J Psychiatr Res 2009; 43: 926–33. 5. Ishida et al. J Occup Environ Med 2020; 62: 641. 6. Sibelli et al. Psychol Med 2016; 46: 3065–80. 7. O’Connor et al. JAMA 2023; 329: 2171–84. 8. Dallé et al. Molecular Brain 2018 11:1 2018; 11: 1–13. 9. Hoge et al. J Clin Psychiatry 2013; 74: 786. 10. Das et al. Front Artif Intell 2024; 7: 1435895.