Specialist in Ophthalmology

Glaucoma is a progressive optic neuropathy characterised by visual field loss and structural damage to the optic nerve. The disease is a leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide, affecting about 3.5% of individuals aged between 40 and 80 years1. While glaucoma-associated visual field loss may be asymptomatic until the late stages, the disease is commonly known as a silent thief of sight. Although early diagnosis of glaucoma remains a clinical challenge, recent advancements in therapeutics have significantly improved patient outcomes. In particular, laser treatment has been advocated to be safe and effective in managing glaucoma. In a recent sharing, Dr. Lai Sum Wai Isabel highlighted the pathophysiology of glaucoma and shared her insights into managing the disease.

Glaucoma is a significant eye disease, attributed to 23% of local blindness cases2. Former estimations suggested that the local prevalence of glaucoma was 3.8%, and the disease contributed to 11% of all visual impairment3. Dr. Lai noted that the prevalence is increasing due to population aging. “Among population aged ≥40 years, the prevalence is about 3 in 100 people, whereas that is about 8 in those aged ≥50 years,” she highlighted. With the progressive loss of retinal nerve fibres, glaucoma manifests as detectable changes to the optic nerve head, thinning of the peripapillary retinal nerve fibre layer, and visual impairment3.

Apart from increasing age, gender and family history are also risk factors for glaucoma development3. Remarkably, primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) has been reported as more prevalent in men than in women, whereas women have approximately 3 times the risk of developing acute angle closure glaucoma compared to men4. Regarding family history, Bhargava et al. (2024) reviewed that individuals with first-degree relatives suffering from glaucoma exhibit substantially elevated glaucoma risks up to 22% compared with 2.3% in controls. Moreover, family history also correlates with greater disease severity5.

Dr. Lai stated that people with severe long-sightedness or short-sightedness are at increased risk of glaucoma. Besides, systemic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, migraine, obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), eye trauma, and steroid use may also increase the risk of glaucoma2. Currently, elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) is the only modifiable risk factor3.

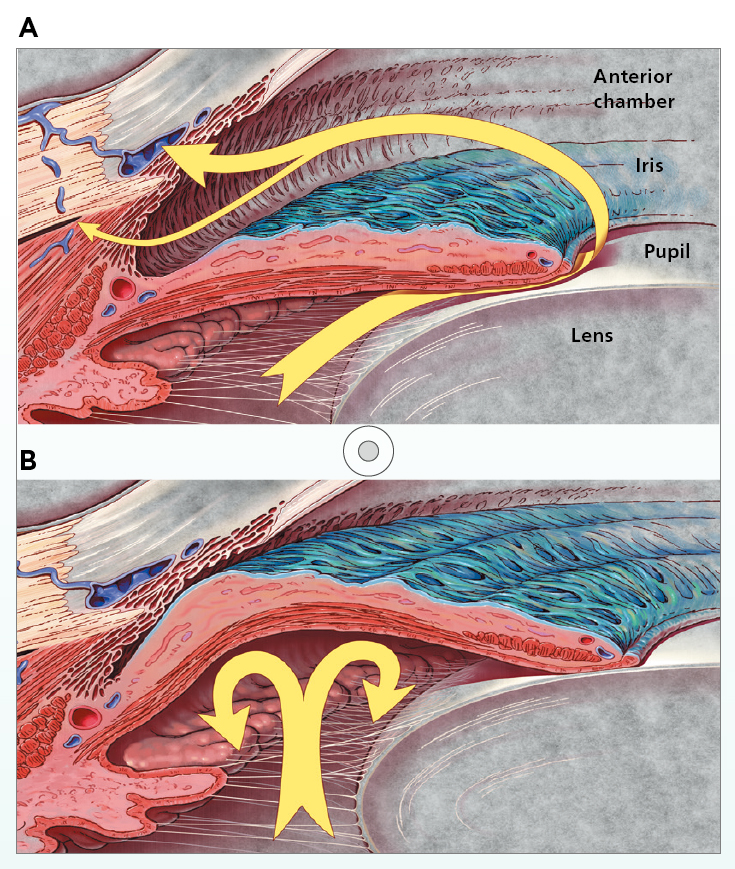

In discussing the pathophysiology of glaucoma, Dr. Lai outlined that the disease can be classified based on structural features into open-angle glaucoma (OAG) and angle-closure glaucoma (ACG). In OAG, the angle in the junction between the iris and cornea remains open as the trabecular meshwork is unblocked by iris tissue, but aqueous outflow by trabecular meshwork and uveoscleral routes is diminished. IOP is transmitted to the axons of retinal ganglion cells at the optic nerve as mechanical stress, leading to cell death. Notably, OAG can be further classified into high-tension or normal-tension glaucoma (NTG), in which IOP lies within the statistically normal range (≤21 mmHg)6. In ACG, the iris is abnormally positioned and blocks aqueous outflow through the iridocorneal angle, resulting in increased IOP (Figure 1A and 1B)7.

Figure 1. Aqueous humour flow (yellow arrow) in A) OAG and B) ACG7

On the other hand, glaucoma can be classified as primary or secondary. Primary glaucoma is defined as an isolated, idiopathic disease of the anterior chamber of the eye and the optic nerve, whereas secondary glaucoma is associated with known predisposing events, including neovascularisation, pseudoexfoliation, pigment dispersion, developmental abnormalities, systemic diseases, drug therapy, or trauma8. As per Dr. Lai, primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most prevalent type in Hong Kong.

Dr. Lai addressed that POAG may not cause any symptoms in the early stages and tends to progress slowly. Nonetheless, when glaucoma is left untreated, the typical disease course is chronic, progressive, and irreversible visual field loss, which may progress to tunnel vision and, ultimately, loss of central vision7.

In contrast, certain glaucoma cases can be acute and progress rapidly, and the patients would experience sudden loss of vision due to acutely elevated intraocular pressure. In such cases, blurred vision (usually unilateral) and halos or rainbows around lights may occur as a result of corneal oedema. Essentially, these patients often report pronounced pain around the eye, as well as headache, nausea and vomiting7.

In addition to impaired vision, glaucoma can have profound consequences on the patient’s well-being and quality of life (QOL). For instance, the patient may experience limitations in performing daily activities, such as driving and reading, as the disease progresses. "There was a patient with glaucoma who avoided leaving home due to the fear of fall or other accidents associated with impaired vision," Dr. Lai highlighted.

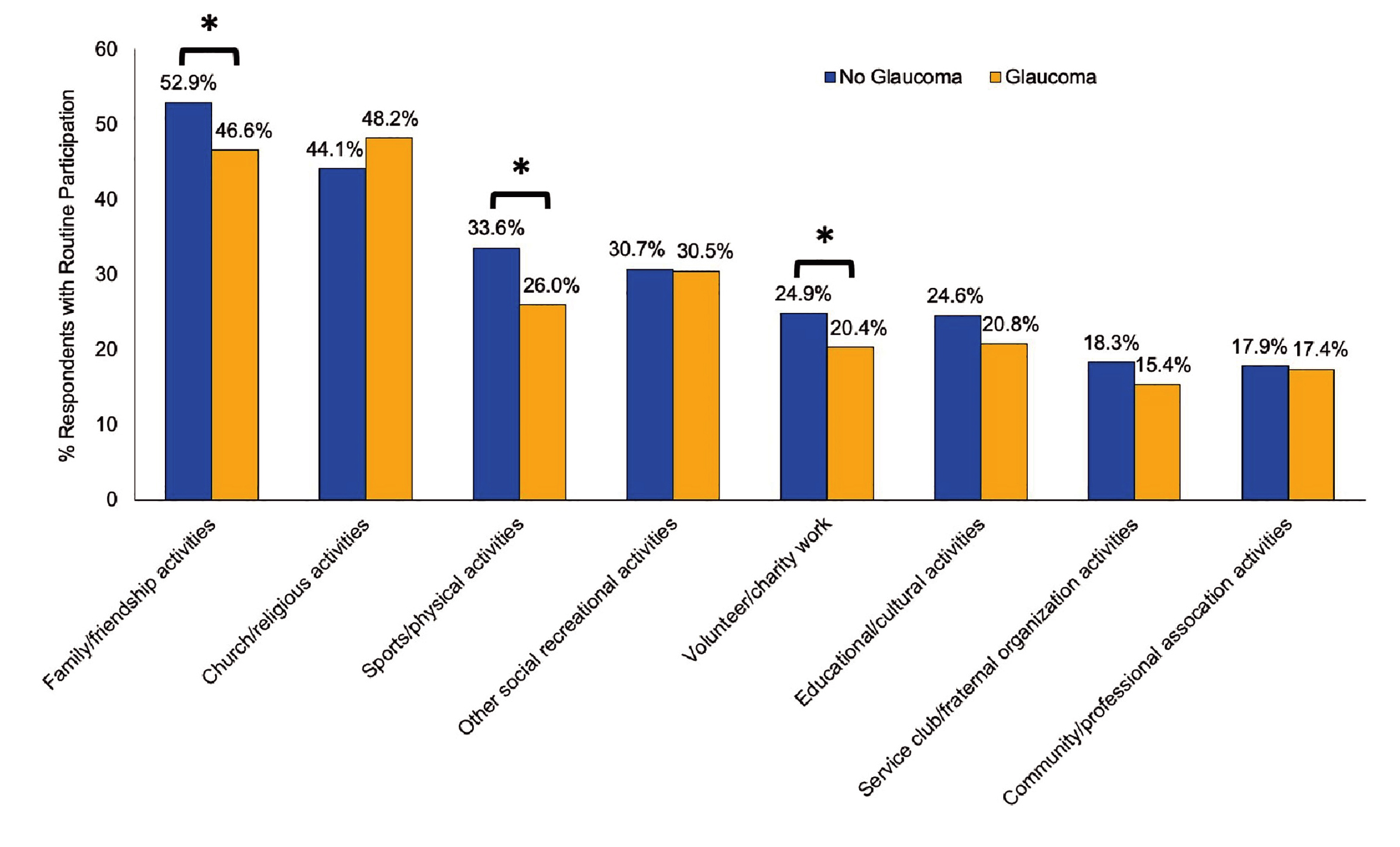

Interestingly, reduced social participation among patients with glaucoma was reported in the study, including health data of 16,369 individuals aged ≥65 years, by Jin et al. (2019). The results indicated that individuals with glaucoma had significantly (p<0.05) reduced participation in family/friendship activities (46.6% vs 52.9%), sports/physical activities (26.0% vs 33.6%) and volunteer/charity work (20.4% vs 24.9%) than those without glaucoma (Figure 2)9.

Figure 2. Participation in social activities for individuals aged ≥65 years with and without self-reported glaucoma9, *p<0.05

As expected, the limited daily activities can lead to psychosocial consequences, such as emotional distress, anxiety, and depression10. Based on Dr. Lai’s observation, patients often experience anxiety when diagnosed with glaucoma. “They would worry if they would be blind and, if so, when would it happen,” she noted. Besides, she mentioned that some patients expressed their regret for delaying the control of glaucoma after learning the irreversible nature of glaucoma-related damages. This highlights the significance of educating individuals at high risk for glaucoma to monitor their eye conditions in order to identify glaucoma early. Besides, Dr. Lai advised that guiding the patients with the appropriate expectations in managing glaucoma is of paramount importance. “The medications are not aimed to instantly improve vision but preventing further worsening of the disease,” she mentioned.

There is no cure for glaucoma. However, timely treatment with appropriate therapies would effectively delay or prevent further damage to vision. Currently, decreasing IOP with eye drops is the mainstay of treating glaucoma, whereas laser treatment, eye surgery, or a combination of these have been demonstrated to be promising as well.

As the first-line treatment, pharmacotherapy for glaucoma has evolved in recent years with the introduction of prostaglandin analogues (PGAs), topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs), beta-blockers, and alpha agonists. PGAs compensate for decreased trabecular meshwork outflow by increasing outflow through the uveoscleral pathway and are the most commonly used medications for treating OAG and ocular hypertension. On the other hand, CAIs and beta blockers lower IOP by targeting the aqueous humour production in the ciliary body. Besides, topical alpha agonists reduce IOP by decreasing the aqueous humour production and increasing the outflow1.

Moreover, prostanoid E2 receptor (EP2) agonists and Rho kinase (ROCK) inhibitors are 2 novel classes of pharmacotherapies which have broadened treatment options against glaucoma. EP2 agonists act by stimulating EP2 receptors leading to an increase in intracellular cAMP and relaxation of smooth muscle in the trabecular meshwork and ciliary muscle, and subsequently improving uveoscleral outflow and trabecular outflow facility11. On the other hand, rho kinase inhibitors reduce IOP through increasing outflow facility, which results from modification of the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm’s canal cytoskeleton and cellular function12.

In evaluating the clinical efficacy of pharmacotherapy, Dr. Lai opined that medications for glaucoma are effective in general. However, various factors govern the treatment outcome, with patient compliance being the foremost factor. She addressed that dosing and side effect profile of medications have to be considered during prescription.

For instance, Dr. Lai noted that it is common to initially prescribe one medication for glaucoma, whereas adjustment to 2 to 3 medications may be needed in certain circumstances. Moreover, some medications need to be applied 2 to 3 times daily. In such cases, patients may have difficulty complying with the dosing requirements, and missing doses are common, particularly among those with full-time employment.

Side effects of medications would be a significant cause of non-compliance for patients. “Red eyes, dry eyes, and discomfort are commonly reported among patients treated with eye drops, particularly those with long-term treatment,” Dr. Lai noted. Indeed, the ocular surface changes induced by long-term glaucoma eye drop treatment, especially by their preservatives, are a major cause of intolerance to the medications. In addition, Dr. Lai noted that prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy syndrome (PAPS) may pose cosmetic concerns for some patients as well as increased surgical difficulty in advanced stages.

Remarkably, topically applied medications can attain sufficient serum levels through absorption into conjunctival and nasal mucosa to trigger systemic effects and potentially interact with other drugs13. Thus, Dr. Lai reminded that the decision on which medication to prescribe depends not only on the type of glaucoma but also on the patient's medical history, tolerability, the side effect profiles of each medication, and the treatment outcomes.

When pharmacotherapy fails to achieve the target IOP and prevent vision loss, laser and surgical procedures are indicated. “Nowadays, more glaucoma cases are detected in younger ages. Laser therapy would be preferred for them since daily medication is not required and the adverse effects of prolonged medication treatment can be avoided,” Dr. Lai highlighted.

Given that various types of laser therapy are currently available for countering glaucoma, selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT), which uses low energy, shorter pulse duration laser to selectively target melanin-containing cells and spare the trabecular meshwork tissue14, has largely supplanted argon laser trabeculoplasty (ALT) because of its favourable safety profile, comparable IOP-lowering efficacy, and ability for repeated treatment applications1.

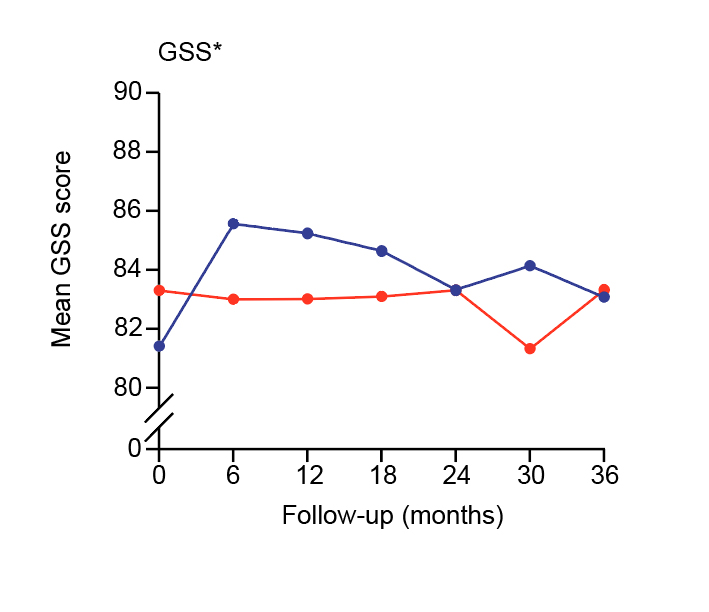

Dr. Lai noted that SLT tends to be applied in earlier stages of glaucoma management nowadays. The efficacy of first-line SLT in ocular hypertension and glaucoma has been demonstrated in the LiGHT trial by Gazzard et al. (2019) involving 718 patients with OAG or ocular hypertension. At 36 months, 74.2% of patients in the SLT group (n=356) required no eye drops to maintain IOP at target. 93.1% of eyes in the SLT group were at target IOP, comparable with the patients receiving eye drops (n=362, 95.0%). Notably, repeated measures analysis showed worse glaucoma symptom scale (GSS), which reflected patient-reported disease and treatment-related symptoms, for the eye drops group at 5 out of 6 timepoints over 36 months (Figure 3)15.

Figure 3. Mean glaucoma symptom scale upon laser and eye drops15, GSS: Glaucoma Symptom Scale (higher scores represent better outcomes)

Moreover, 11 eyes (1.8%) in the eye drops group required surgery to lower IOP, whereas none in the SLT group required the treatment. Furthermore, the average cost per patient for ocular surgery over 36 months was significantly less for the SLT group than the eye drops group (unadjusted difference: -£134, p=0.002) and for all ophthalmology costs including SLT and drops (unadjusted difference: -£451, p<0.001)15.

Apart from high-tension disease, a recent trial by Nitta et al. (2024), which recruited 100 patients with NTG, suggested that SLT may be an effective and safe treatment option for NTG, as either a first-line or second-line treatment16.

Surgery has long been performed to limit optic nerve damage and to minimise visual loss in patients with glaucoma when both eye drops and laser therapy fail to control the disease. As per Dr. Lai, less than 50% of local patients with glaucoma require surgical treatment. Notably, she highlighted that patients were conservative towards surgery for glaucoma in the past, but there is an increasing proportion of patients who choose to receive minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) in earlier stages.

Conventional trabeculectomy is a technique to divert aqueous from the anterior chamber into the subconjunctival space by creating a new drainage pathway. In contrast, MIGS generally cause minimal trauma with little or no scleral dissection or conjunctival manipulation. Currently, there are 3 main categories of MIGS, namely 1) angle-based MIGS, which enhance trabecular outflow by bypassing or manipulating angle structures, 2) suprachoroidal MIGS, which increases uveoscleral outflow through a suprachoroidal drainage shunt, and 3) subconjunctival MIGS, which creates an aqueous outflow pathway into the subconjunctival or sub-Tenon’s space17. Dr. Lai opined that the risk in traditional surgery is higher while the success rate is less than in other eye surgeries, such as those for cataracts.

While earlier MIGS would yield better outcomes, an assessment of suitability for the procedure is required. Dr. Lai outlined that patients with early- or mid-stage glaucoma would be preferred. “Some patients with prolonged medications may develop structural changes in the conjunctiva and may not be suitable for MIGS,” she explained. Essentially, she added that the improvement by surgery for late-stage glaucoma would be modest. Hence, early planning for treatment is advisable.

General population screening for glaucoma can potentially help early identify patients with the disease. However, recommendations for glaucoma screening vary significantly from organisation to organisation and are only recommended in specific situations18. Dr. Lai expressed that although Hong Kong is a resourceful place, screening for glaucoma for the general population is difficult in the view of public health. “Screening among high-risk populations is more cost-effective as the chance of identifying people with glaucoma is higher,” she suggested.

Similarly, existing literature advocated screening high-risk populations, which is helpful in diagnosing and treating larger proportions of the general population benefiting from a higher positive-predictive value for screening protocols and also cost-effective. Accordingly, the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) currently recommends screening for glaucoma at age 40. Moreover, it is advocated that certain factors should prompt an individual to be screened earlier, including diabetes, high blood pressure, or a family history of eye disease18.

Undoubtedly, ophthalmologists play a vital role in treating glaucoma. Nonetheless, the overall management of the disease involves the support of a multidisciplinary team of professionals and stakeholders. “The role of family doctors is crucial since they are the first contact point for patients.” Dr. Lai stated. She highlighted that family doctors are essential in identifying high-risk individuals, such as those who have a family history of glaucoma. Their involvement in educating patients on the risk of glaucoma substantially enhances public awareness of the disease. This, in turn, facilitates early identification and timely treatment.

Dr. Lai pointed out that people would seek help from optometrists when experiencing eye problems. “While early-stage glaucoma usually yields no symptoms, the mild increase in intraocular pressure can be measured during eye tests by optometrists,” she emphasised the role of optometrists in identifying potential glaucoma cases.

Of course, the participation of patients is a crucial determinant of treatment success. In this regard, Dr. Lai advised that, given glaucoma is a chronic disease with no apparent symptoms in the early stage, regular examination of eye conditions among high-risk populations is recommended. More importantly, recent medical advances have led to better control of glaucoma. A positive attitude and persistently complying with the treatment will help maintain the target IOP and prevent further visual impairment.

References

1. Wagner et al. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 2022; 6: 618. 2. The Hong Kong Ophthalmological Society. Glaucoma. 2024. 3. Lai et al. Eye 2022; 37: 1717. 4. Rizk et al. AJO International 2024; 1: 100013. 5. Bhargava et al. J Glaucoma 2024; 33: S40–4. 6. Esporcatte et al. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2016; 79: 270–6. 7. Guptq and Chen. Glaucoma. Am Fam Physician 2016; 93: 668–74. 8. Wiggs. Glaucoma. Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences 2014. 9. Jin et al. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0218540. 10. Kopilaš and Kopilaš. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024; 11. DOI:10.3389/FMED.2024.1402604. 11. Fuwa et al. Journal of Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2018; 34: 531–7. 12. The Asia Pacific Glaucoma Society. Asia Pacific Glaucoma Guidelines 4th Ed 2024: 126. 13. Detry-Morel. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol 2006; 299: 27–40. 14. Garg and Gazzard. Eye (Lond) 2018; 32: 863–76. 15. Gazzard et al. The Lancet 2019; 393: 1505–16. 16. Nitta et al. BMJ Open Ophthalmol 2024; 9. DOI:10.1136/BMJOPHTH-2023-001563. 17. Ang et al. Bioengineering 2023; 10: 1096. 18. Gunzenhauser and Coleman. J Glaucoma 2024; 33: S9–12.