Editor-in-Chief, V·Pulse

Doctor at the National Health Services (NHS), United Kingdom (UK)

Insomnia disorder is a prevalent condition that affects millions globally (perhaps including you!) While often being overlooked, insomnia disorder is characterised by difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep over a sustained period. Apart from sleep quality, the disorder increases the risk of developing severe medical and psychiatric comorbidities and can exacerbate existing conditions1. Moreover, the socioeconomic cost associated with the disorder is substantial as well. Despite the high local prevalence, it is uncommon for people affected by insomnia disorder to seek help from healthcare professionals2, which reflects the timely need for sleep health literacy promotion. This article aims to review the impacts of insomnia disorder in various aspects and highlight the advances in treating the disorder.

Difficulty in falling asleep is a common complaint among the general population globally. Probably, most of us have experienced this as well. However, the question worth noting is what qualifies insomnia to be considered a disorder. According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) International Classification of Sleep Disorders - 3rd Edition (ICSD-3), insomnia disorder is defined as having frequent and persistent difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, which is associated with daytime consequences and is not attributable to environmental circumstances or inadequate opportunity to sleep.

Furthermore, insomnia disorder is classified as chronic if the symptoms persist for at least 3 months and occur at least 3 times per week. In contrast, cases that continue for less than 3 months are considered short-term3. Of note, the definition of insomnia disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition (DSM-5) is consistent with the criteria established in ICSD-31. Remarkably, if the sleep complaints are fully explained by another physical, psychiatric or sleep disorder, the case does not meet the diagnostic criteria for insomnia4.

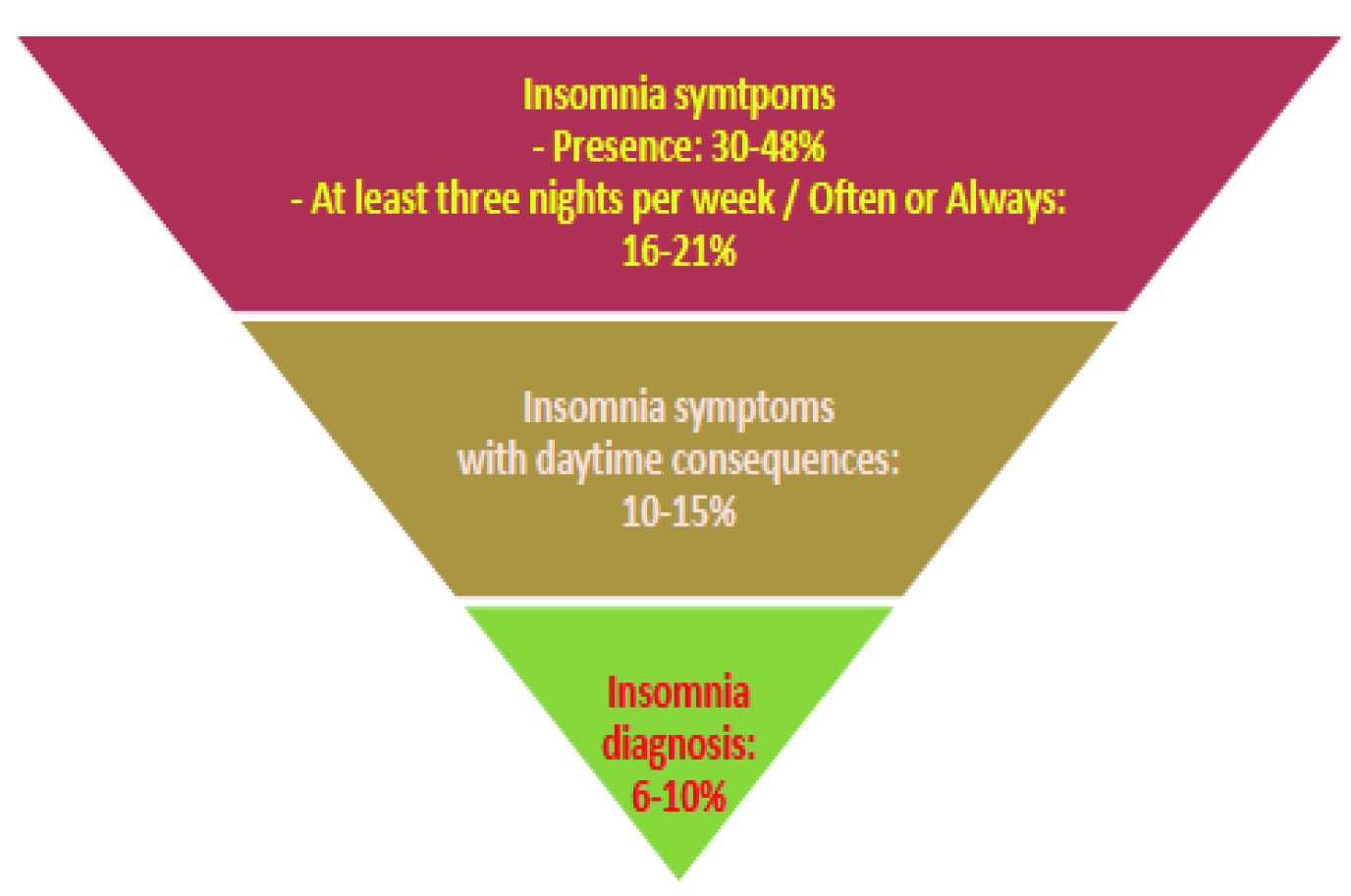

Former population-based studies suggested that approximately 30% of adult samples from different countries report one or more of the symptoms of insomnia, including difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, waking up too early, or poor quality of sleep5. In Hong Kong, according to the Population Health Survey 2014/15 by the Department of Health (DoH), up to 48.0% of community-dwelling persons aged 15 and above had experienced sleep disturbance, such as difficulty in falling asleep within 30 minutes, intermittent awakenings, difficulty in maintaining sleep during the night, etc., whereas insomnia was diagnosed in 6-10% of the population (Figure 1)6.

Figure 1. Local prevalence of insomnia symptoms and diagnosis6

A recent analysis of 12,022 individuals aged 15 or above extracted from the Population Health Survey 2014/15 by Bedford et al (2022) revealed that female gender, lower household income, lower education level, mental health condition and physical health condition were significantly associated with both insufficient and disturbed sleep (all p <0.05). Remarkably, the report further suggested that harmful alcohol consumption, insufficient physical activity and current smoking are modifiable risk factors for sleep disturbances7.

Essentially, insomnia is strongly associated with mental disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). For instance, while most people with major depressive disorder (MDD) report insomnia, those with insomnia are at increased risk of developing depressed mood4.

Apart from the factors above, older age is also a well-identified risk factor for insomnia. The increased prevalence of insomnia among older adults can be attributed to the partial decline in the functionality of sleep control systems and the presence of comorbid medical conditions. In particular, although work-life balance has been advocated nowadays, working night or rotating shifts are reported significant risk factors for insomnia5. Nonetheless, it is essential to note that these factors do not independently cause insomnia, but instead, they are precipitants of insomnia in people predisposed to the disorder.

Sleep is essential for memory consolidation, brain reactivity and emotion regulation8. It is not surprising that people with insomnia disorder are susceptible to a broad spectrum of pathophysiological and psychiatric impacts. For instance, a population-based prospective study in Norway (2014) comprising 24,715 people in the working population demonstrated that chronic insomnia significantly increased the risk of various physical and mental disorders, including depression (odds ratio [OR]: 2.38), anxiety (OR: 2.08), fibromyalgia (OR: 2.05), rheumatoid arthritis (OR: 1.87), osteoporosis (OR: 1.52), asthma (OR: 1.47), and myocardial infarction (OR: 1.46)9.

More recently, a cross-sectional study involving about half a million Spanish workers by Valenzuela et al (2022) indicated that self-reported poor sleep was associated with a higher likelihood of presenting cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors. Remarkably, the study further suggested that specific sleep characteristics, including short duration, restfulness, and difficulties falling asleep, were associated with higher CVD risk scores than those without sleep problems10. These findings among working populations imply increased healthcare resource utilisation, medical expenses, and reduced productivity.

Interestingly, a local survey involving 1,691 Chinese adults by Zhao et al (2019) revealed that short sleep duration and insomnia symptoms were associated with lower happiness levels. In the study, happiness was estimated based on the subjective happiness scale (SHS) and the one-item global happiness index (GHI), whereas information on sleep duration and insomnia symptoms (such as difficulty in initiating sleep) was collected from the participants via phone interviews. The results demonstrated that people with less than 6 hours of sleep per day had lower SHS and GHI than those with at least 8 hours. In particular, the associations were stronger in younger adults and women8.

While insomnia disorder is associated with impaired attention, memory, problem-solving, and reaction time compared to those without insomnia disorder, these symptoms contribute to an increased risk of work and motor vehicle accidents and an increased risk of falls and fractures, especially among older populations1.

Apart from the impacts on people with insomnia, the societal cost burden of the disorder is substantial. Taddei-Allen (2020) reviewed that the aggregate total of direct and indirect insomnia healthcare costs has been estimated at up to $100 billion US dollars per year. Of note, the review highlighted the potential impacts of adverse events associated with insomnia treatment, such as cognitive impairment11. Hence, safety profiles and cost-effectiveness of insomnia treatments have to be considered in managing patients with insomnia disorder.

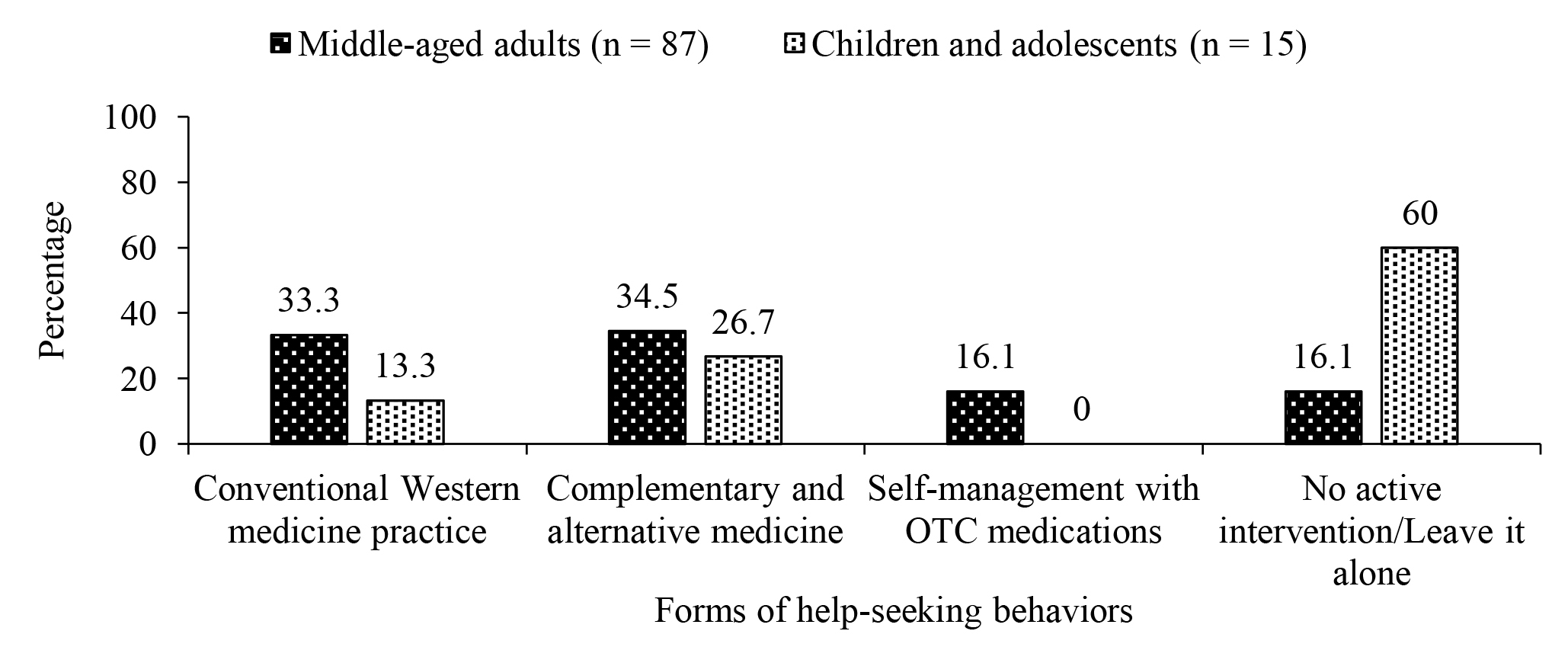

Despite the significant adverse impacts, the majority of people with insomnia do not seek help for the disorder. A local survey by Liu et al (2016), which recruited 2,231 middle-aged adults (54.2% females, mean age: 45.8 years) and 2,186 children and adolescents (51.9% females, mean age: 13.4 years), reported that only 40% of adults and 10% of children and adolescents with insomnia reported having sought treatment for insomnia2.

Among those who sought help for insomnia, only 33.3% of adults and 13.3% of children and adolescents preferred conventional Western medicine, whereas a higher proportion of participants with insomnia chose complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies (34.5% of adults and 26.7% of children and adolescents, Figure 2). The survey further reported that female gender, higher family income, higher severity of insomnia, chronic medications, and psychiatric disorders were factors associated with help-seeking behaviours in adults. The presence of morning headaches was associated with help-seeking in children and adolescents2.

Figure 2. Help-seeking behaviours for insomnia among middle-aged adults, children and adolescents2, OTC: over-the-counter

Therefore, the report highlighted the need to promote sleep health literacy and improve the accessibility of existing evidence-based insomnia treatments. Given the substantial proportion of individuals on CAM, investigations on the efficacy and safety profiles of the therapies are warranted.

Most insomnia can be effectively treated through medications or cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). By virtue of the limitations of pharmacologic treatment for insomnia, such as potential dependence and tolerance upon long-term usage, the non-pharmacologic approach has gained increasing attention in the past decade.

There are various non-pharmacologic approaches for insomnia, including stimulus control, sleep restriction therapy, relaxation therapy, and sleep hygiene education12. Among them, CBT-I has been recommended by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM)13 and the American College of Physicians (ACP)14 as the first-line treatment for chronic insomnia in adults. CBT-I is a multi-component treatment targeting behavioural, cognitive, and physiological factors that perpetuate insomnia and aims to modify and alter maladaptive behaviours and distorted beliefs about sleep and insomnia15.

Although clinical data have proven the clinical benefits of CBT-I, there are barriers preventing CBT-I from being more widely used in clinical practice. In reality, the availability of providers and cost constraints are major obstacles to implementing CBT-I. Moreover, the considerable time commitment by the patients for CBT-I also prevents its application. In light of this, implementing CBT-I through the internet, or digital CBT-I, would help reduce the time required and improve the accessibility12.

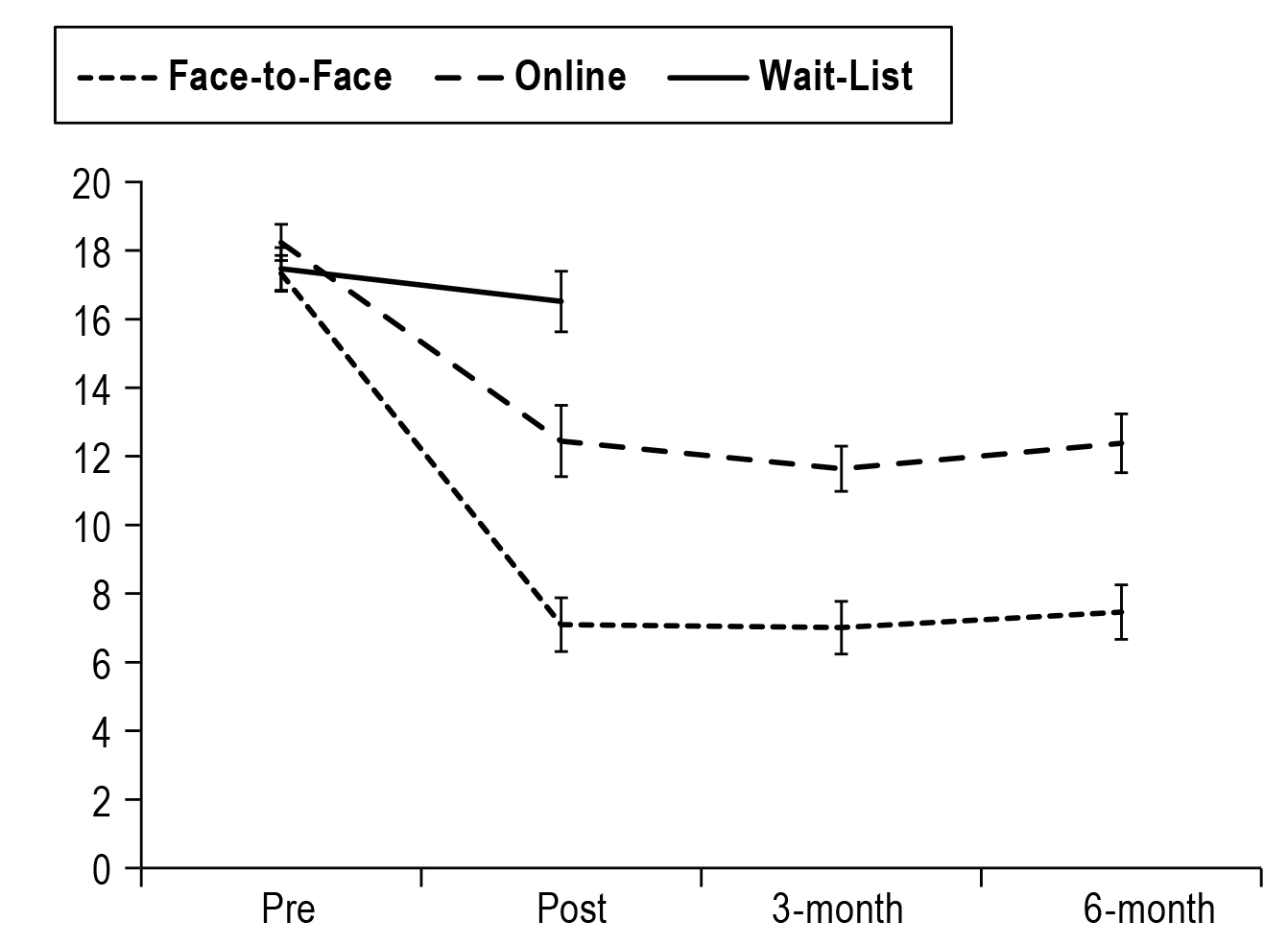

The comparison of the efficacy of digital and individual face-to-face CBT-I was illustrated in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) by Lancee et al (2016). At the follow-up after either 3 months or 6 months, both digital (n=30) and face-to-face CBT-I (n=30) showed significantly larger treatment effects than the wait-list group (n=30) on insomnia severity (Figure 3). Nonetheless, face-to-face treatment yielded a statistically larger treatment effect on insomnia severity than the digital approach at all time points. The results also indicated that face-to-face treatment outperformed the digital approach on depression and anxiety outcomes16. Although digital CBT-I was shown to be less efficacious than face-to-face treatment, the digital approach offers a cost-effective alternative to and complements face-to-face treatment.

Figure 3. Insomnia severity index scores for face-to-face, online and wait-list groups16

Figure 3. Insomnia severity index scores for face-to-face, online and wait-list groups16

While not all patients with insomnia benefit from CBT-I, pharmacologic treatment may be required based on the shared decision with patients on the benefits, risks, and costs associated with the use of medications14. Currently, pharmacologic therapies for the treatment of insomnia include benzodiazepines (BZDs) and the non-BZD hypnotic “Z-drugs”, the dual orexin receptor antagonist (DORA), the melatonin receptor agonist, and the first-generation histamine antagonist. However, there is insufficient evidence to determine the efficacy or the benefit-to-risk ratio of many of these therapies. Thus, clinical guidelines, such as ACP, do not make specific recommendations for any single medication12.

Hypnotics are among the most commonly prescribed medications for insomnia, whereas current evidence supports the efficacy of these agents in improving sleep quality and quantity17. Besides, DORA is another class of pharmacologic treatment for insomnia worth noting. Orexin neuropeptides and their associated receptors, OX1R and OX2R, are critical for sleep-wake regulation. The DORAs work by selectively blocking the binding of orexin neuropeptides to their respective receptors and, in turn, promote sleep through a decrease in arousal signalling. Essentially, orexin receptor antagonists have been found to shorten rapid eye movement (REM) latency and increase total sleep time (TST), mainly by increasing the time spent in REM sleep.

Furthermore, DORAs do not appear to be associated with tolerance, withdrawal, or rebound insomnia if abruptly discontinued. Nonetheless, the mechanism of action of DORAs suggests that daytime sleepiness would be further exacerbated in patients with narcolepsy. In this regard, DORAs are contraindicated in these patients12.

Insomnia disorder is a prevalent and solid condition leading to significant impairment in quality of life for patients and substantial socioeconomic costs. While the disorder is generally under-identified and under-treated, promoting sleep health literacy is an essential component in containing the disorder from the public health perspective. In line with the development of CBT-I, advances in delivery approaches are expected to enhance the accessibility and efficacy of the treatment. On the other hand, the availability of new classes of medication for insomnia, such as DORAs, offers patients more options. While clinical evidence has demonstrated the efficacy and safety of the medications in countering insomnia symptoms, further investigations on the clinical performance of combined treatment with pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatments would provide insight into optimising the management protocol for insomnia disorder.

References

1. Roach et al. Int J Neurosci 2021; 131: 1058–65. 2. Liu et al. Sleep Med 2016; 21: 106–13. 3. Sateia et al. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 2017; 13: 307–49. 4. Krystal et al. World Psychiatry 2019; 18: 337. 5. Roth. J Clin Sleep Med 2007; 3: S7. 6. Centre for Health Protection. NCD Watch 2018 - Long and Sleepless Nights. . 7. Bedford et al. BMJ Open 2022; 12: e058169. 8. Zhao et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16. DOI:10.3390/IJERPH16122079. 9. Sivertsen et al. J Sleep Res 2014; 23: 124–32. 10. Valenzuela et al. Eur J Clin Invest 2022; 52. DOI:10.1111/ECI.13738. 11. Taddei-Allen et al. Am J Manag Care 2020; 26: S91–6. 12. Rosenberg et al. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2021; 17: 2549–66. 13. Sateia et al. J Clin Sleep Med 2017; 13: 307. 14. Qaseem et al. Ann Intern Med 2016; 165: 125–33. 15. Chan et al. Neurotherapeutics 2021; 18: 32–43. 16. Lancee et al. Sleep 2016; 39: 183–91. 17. Madari et al. Neurotherapeutics 2021; 18: 44.