Editor-in-Chief, V·Pulse

Doctor at the National Health Services (NHS), United Kingdom (UK)

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common type of glomerulonephritis worldwide. The disease is a progressive inflammatory kidney disease that requires long-term treatment to reduce the risk of progression to kidney failure1. Nonetheless, 20% to 40% of patients with IgAN eventually develop end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) within 25 years, and kidney transplantation remains one of the prime therapeutic options in these individuals. Essentially, recurrence of IgAN post renal transplant can occur with a frequency ranging from 20% to 60%2. There is currently no specific treatment option available for recurrent IgAN, so strategies for improving graft survival are crucial. The aim of this article is to discuss the pathophysiology and management of IgAN. Essentially, preventive strategies addressed in existing literature for recurrent IgAN, and prolonging survival of kidney graft will be reviewed.

The reported global incidence of IgAN is approximately 2.5/100,000 population per year, according to Storrar et al. (2022). However, the disease has a distinct geographical variation with an increased prevalence in Far East Asia compared to Europe but is less prevalent in Africa3. Remarkably, 30% to 40% of IgAN patients in East and Southeast Asia develop a progressive form of the disease, typically necessitating renal replacement therapy within two decades of diagnosis4. In Hong Kong, IgAN accounts for 35% of all primary glomerulonephritis, with the peak incidence between the ages of 25 and 34 years5.

IgAN is a subtype of glomerulonephritis induced by the accumulation of IgA-containing immune complexes in the glomeruli that initiate a cascade of inflammatory events causing irreversible glomerulosclerosis leading to ESKD. Besides affecting the kidneys, the disease also has a detrimental effect on the patients' quality of life (QOL) and increases the risk of premature death. Unfortunately, there are no early signs or symptoms of IgAN. Thus, many patients remain undiagnosed until they present with of chronic kidney disease (CKD)6. Clinically, the diagnosis of IgAN is incidental during a routine health check-up by urinalysis. The most common renal manifestation of IgAN is isolated microscopic haematuria, which accounts for 25% of the cases, while macroscopic haematuria and proteinuria are also prevalent. Nevertheless, IgAN has diverse clinical presentations and variable outcomes5.

Although the mechanism through which the normal physiological process of IgA production becomes dysregulated leading to IgAN remains elusive, the MEST-C score has been developed to determine the risk of IgAN progression. Independent predicting factors for renal outcomes, including mesangial hypercellularity (M), endocapillary hypercellularity (E), segmental glomerulosclerosis (S), tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis (T), and the presence of crescents (C) are involved in the estimation of the MEST-C score. In addition, variables such as age, sex, ethnicity, proteinuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), blood pressure, the use of immunosuppression and renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockade at or prior to biopsy are also reported to reflect the risk of progression in IgAN3.

Accurate risk stratification at diagnosis and predicting treatment response of IgAN remains challenging. Clinically, the diagnosis of IgAN is documented based on the predominant IgA deposition in renal mesangium demonstrated in the histological examination of a renal biopsy, whereas clinicopathological parameters, including blood pressure, eGFR and amount of proteinuria, also provide an insight into the risk of the disease progression4.

Currently, there are no cure for IgAN, therefore, the aim of IgAN management is to delay disease progression to advanced renal failure5. While there is heterogeneity in the approaches adopted internationally, supportive intervention remains the primary mode of management in IgAN4. According to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2021 guidelines, supportive care for IgAN involves rigorous lowering the modifiable risk factors which includes adequate blood pressure control, optimising RAS inhibition, assessing and addressing cardiovascular risk, and lifestyle changes, including dietary sodium restriction, smoking cessation, weight control, and exercise, as appropriate (Figure 1)7.

Figure 1. Key elements in supportive therapy in IgAN (modified from Floege J et al. Semin Immunopathol 2021)

The potent effects of uncontrolled hypertension and proteinuria on the course of the disease remains important, thereby controlling the blood pressure and proteinuria is a crucial element when managing IgAN. RAS antagonism with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or an angiotensin II-receptor blocker (ARB) is a first-line treatment used in managing IgAN recommended by the clinical guidelines8.

A meta-analysis of 11 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) by Cheng et al. (2009) demonstrated that ACEI⁄ARBs offered significant renoprotective effects on the renal function (p<0.00001) and reduces the proteinuria (p<0.00001) in patients with IgAN compared to the control group, regardless of their blood pressure and renal function9. To substantiate these findings, a retrospective analysis of data from the Toronto Glomerulonephritis Registry by Reich et al. (2007) showed that patients with IgAN treated with an ACEI/ARB to control blood pressure had a better preservation of kidney function than those not treated with ACEI or ARBs. The beneficial effects of ACEI/ARB were potentially related to the effects on both proteinuria and blood pressure10. However, literature has advocated on up-titrating the RAS blockers dose to the maximally tolerated doses for IgAN patients, even if blood pressure remains well-controlled; the rationale behind this is to reduce the proteinuria further8.

Aside from blood pressure control, minimising the risk of CKD remains paramount while managing patients with IgAN. The KDIGO 2021 guidelines suggested that a 6-month course of glucocorticoid therapy should be considered for patients who remain at high risk of progressive CKD despite maximal supportive care. However, the risk of treatment-emergent toxicity should be discussed with patients prior to commencing such treatment11.

Notably, IgA1 has a galactose-deficient O-glycans (Gd-IgA1) in the hinge region and is produced by the plasma cells in response to class switching B-cells in the mucosa. During the production of Gd-IgA1, toll-like receptor-9 (TLR-9) is overexpressed in the tonsils after an upper respiratory mucosal infection, including tonsillitis, and activation of TLR-9 produces a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL) in the tonsillar B cells and a B cell-activating factor (BAFF). Both of these, in the absence of T cell dependent pathways, generate antibody-producing plasma cells that produce Gd-IgA1. Therefore, tonsillectomy appears to impede the first step in the pathway that produces Gd-IgA1, thereby depleting Gd-IgA1 among IgAN patients, would potentially improve the symptoms of the disease12. However, the clinical evidence on the benefits of tonsillectomy in IgAN was inadequate and inconsistent, especially in the Caucasian population. Hence, the KDIGO guidelines does not advocate tonsillectomy in Caucasian patients with IgAN11.

Kawabe and Yamamoto (2023) reported that 15% to 20% of patients with IgAN are likely to progress to ESKD in approximately 10 years after diagnosis of IgAN. Currently, kidney transplantation remains the most effective treatment for patients with ESKD, offering improved longevity and QOL13. Unfortunately, IgAN often recurs in kidney grafts, and the reported incidence of recurrence ranges from 9% to 53%. The discrepancies in the incidence rates can partially be explained by the variable indications of graft biopsy in different centres and the differences in the duration of post-transplant follow-up since the rate of recurrence increases with lengthier post-transplant follow-ups14. An analysis of 28 years of Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry (ANZDATA) transplant data by Jiang et al. (2018) revealed that the recurrence rate for IgAN at 5 and 10 years were, respectively, 5.4% and 10.8% (Figure 2)15. These findings suggest that the recurrence of IgAN is likely a time-dependent event, supporting the hypothesis that a higher probability of recurrence correlated to the longer follow-up time.

Figure 2. Recurrence-free survival for various categories of glomerulonephritis (GN)15, GN-FSGS: Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis, GN-MN: Membranous Nephropathy, GN-MCGN: Mesangiocapillary Glomerulonephritis

While the clinical presentation and outcomes of recurrent IgAN remains variable, most recurrent cases are diagnosed via the graft biopsies performed for clinical reasons. Notably, haematuria is not a reliable indicator for recurrence since it is absent in about 64% of cases diagnosed with IgAN in the native kidney14. Some studies suggested that the level of Gd-IgA1 at the time of renal biopsy significantly correlates with disease progression16. Berthoux et al. (2017) demonstrated that the serum levels of Gd-IgA1-specific IgG autoantibody was an independent risk factor for the recurrence of IgAN in the allograft17. In contrast, a recent cohort study by Jäger et al. (2022) reported that the predictive value of known biomarkers, such as serum Gd-IgA1 and IgA-IgG immune complexes for IgAN recurrence cannot be confirmed2. Thus, findings from existing analyses on biomarkers for IgAN recurrence remain inconsistent. However, it is important to note that young age at renal transplantation, male gender, and rapidly progressive course of the disease before transplantation are associated with a higher risk of IgAN recurrence14.

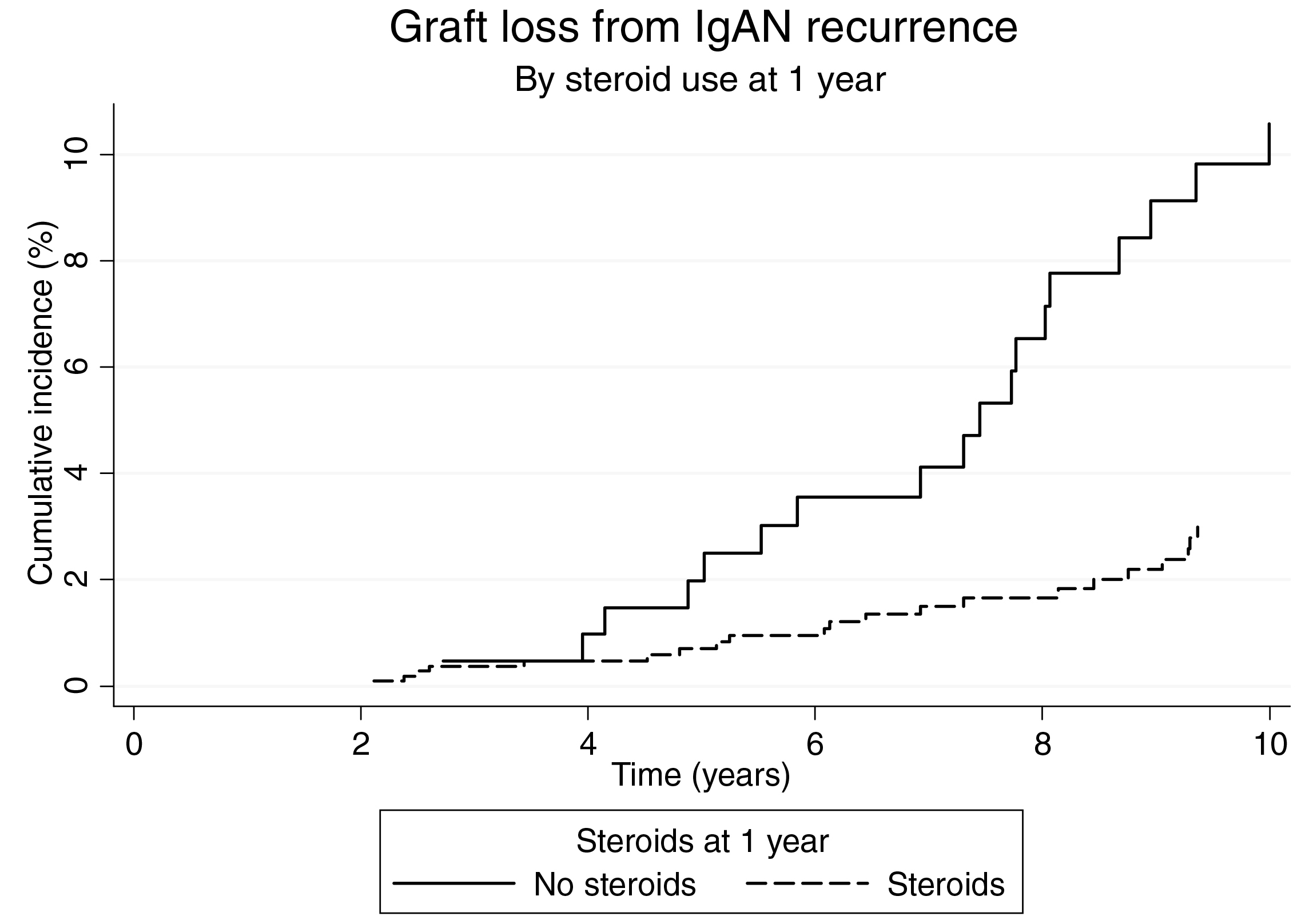

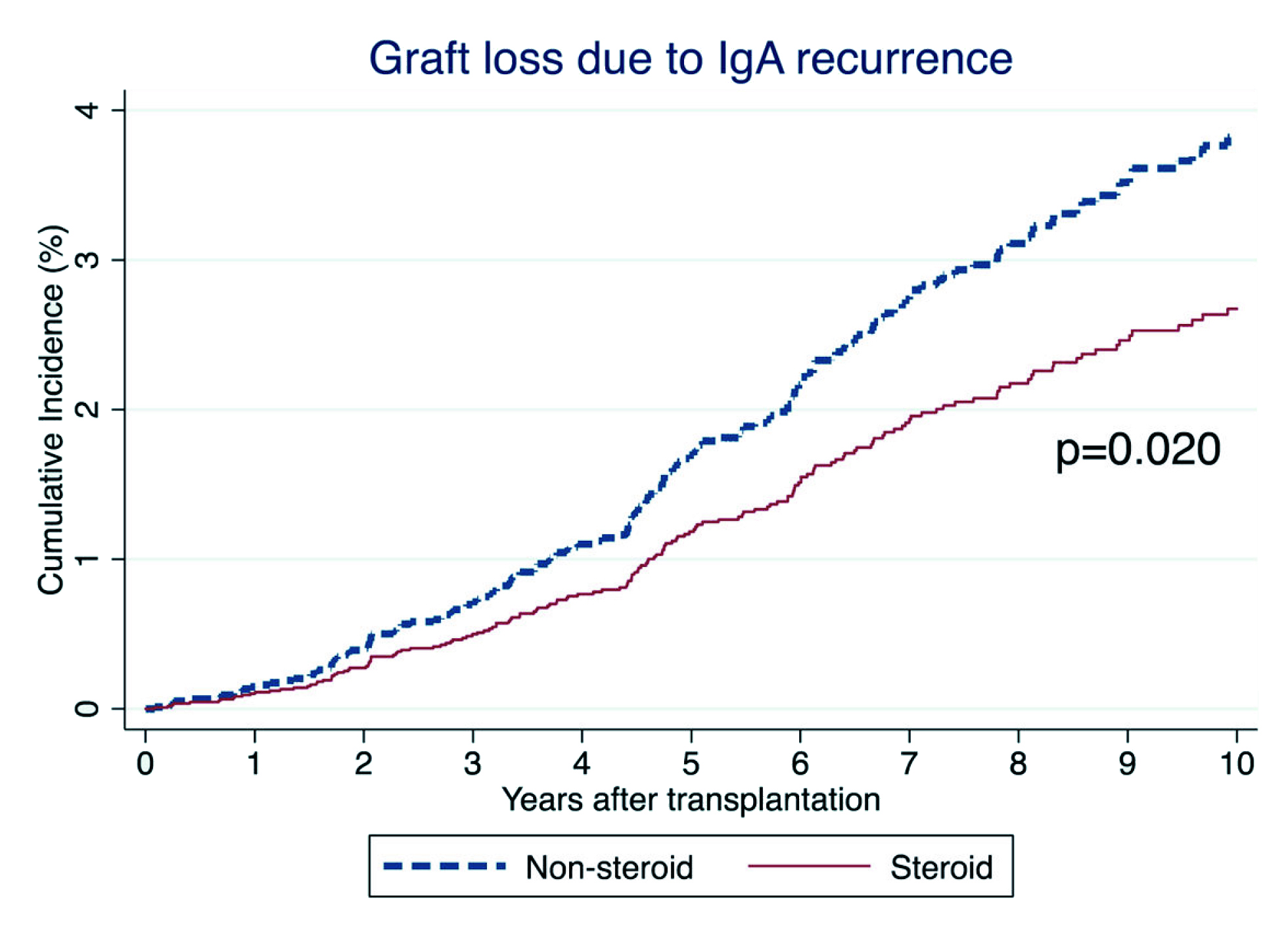

Currently, there are no universally accepted guidelines for treating recurrent IgAN. The main goals of therapy are to prevent the recurrence and prolong the life of kidney grafts. Interestingly, a survival analysis on patients who received their first kidney transplant for IgAN in ANZDATA by Clayton et al. (2011) suggested that steroid use was strongly associated with a reduced risk of recurrence (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.50, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.30–0.84, Figure 3)18. These findings were confirmed by a subsequent retrospective analysis of the United Network of Organ Sharing/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (UNOS/OPTN) database (2018), which included 9,690 adults with IgAN who received their first kidney transplant between 2000 and 2014. The analysis concluded that 15.43% of 1,238 recipients experienced graft loss due to IgAN recurrence. Remarkably, steroid use was associated with a lower risk of IgAN recurrence at multivariate analysis (subdistribution HR: 0.666, 95%CI: 0.482-0.921, p=0.014, Figure 4)19. Thus, early steroid withdrawal among kidney transplanted patients with IgAN resulted a higher risk of graft loss secondary to the disease recurrence.

Figure 3. Cumulative incidence of graft loss due to recurrent IgAN in ANZDATA analysis18

Figure 4. 10-year unadjusted cumulative incidence of graft loss due to IgA recurrence in UNOS/OPTN database19

The KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients advocated the treatment for the recurrence of IgAN in transplanted patients should aim to reduce proteinuria, optimise blood pressure, and reduce inflammation. The guideline highlighted that ACEI and ARB reduces the risk of proteinuria and possibly preserve kidney function in recurrent IgAN20. Careful blood pressure control is crucial for maintaining graft function, particularly in patients with proteinuria >1g/day. Moreover, close monitoring of the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is essential, particularly when medications are used14.

Apart from conventional treatments, the phase IIb NEFIGAN trial by Fellström et al. (2017) reported a reduction in proteinuria and stabilisation of renal function after budesonide administration in patients with IgAN, suggestive of a potential role of the therapy in patients with IgAN recurrence after kidney transplant21. It is without doubt that a better understanding on the pathogenesis of IgAN would help facilitate a better treatment plan and outcome which may prevent the progression of the disease and its recurrence.

Despite the high recurrence rate and effect on graft survival, kidney transplantation is the last resort yet the best treatment option for patients with ESKD due to IgAN. Nonetheless, Hong Kong has one of the lowest rates of organ donation globally. A survey involving 1,000 local Chinese residents by Teoh et al. (2020) revealed that 31.3% were willing to donate their organs after death, while 43.3% remained indecisive, and 25.4% refused. Among those who were willing to donate their organs after death, only 34.2% had registered with the Centralised Organ Donation Register (CODR)22.

The survey highlighted that potential organ donors lack the determination, and this was one of the main reasons for not registering with the CODR. In addition, 32.8% of the interviewees were not aware of the ways to register as prospective organ donor22. Therefore, this survey demonstrated that more effort was required to educate the public on the importance of organ donation. Optimising the registration procedure would undoubtedly increases the number of organ donors, whereas encouraging those who were indecisive through promotional campaigns and social media platforms is expected to enhance their acceptance towards organ donation. In this regard, more effort should be driven from the healthcare professionals apart from the government and non-governmental organisations. In conclusion, it is essential to appreciate that, as our knowledge and scientific capabilities regarding the safety and availability grows and evolve, donors who in the past would not have been considered as donors are now able to provide the gift of life to others.

References:

1. Jhaveri KD, Bensink ME, Bunke M, Briggs JA, Cork DMW, Jeyabalan A. Humanistic and Economic Burden of IgA Nephropathy: Systematic Literature Reviews and Narrative Synthesis. Pharmacoecon Open 2023. DOI:10.1007/S41669-023-00415-0. 2. Jäger C, Stampf S, Molyneux K, et al. Recurrence of IgA nephropathy after kidney transplantation: experience from the Swiss transplant cohort study. BMC Nephrol 2022; 23. DOI:10.1186/S12882-022-02802-X. 3. Storrar J, Chinnadurai R, Sinha S, Kalra PA. The epidemiology and evolution of IgA nephropathy over two decades: A single centre experience. PLoS One 2022; 17: e0268421. 4. Selvaskandan H, Cheung CK, Muto M, Barratt J. New strategies and perspectives on managing IgA nephropathy. Clinical and Experimental Nephrology 2019 23:5 2019; 23: 577–88. 5. Ho K. IgA nephropathy: in Hong Kong. The Hong Kong Practitioner 2001; 23. 6. Kwon CS, Daniele P, Forsythe A, Ngai C. A Systematic Literature Review of the Epidemiology, Health-Related Quality of Life Impact, and Economic Burden of Immunoglobulin A Nephropathy. J Health Econ Outcomes Res 2021; 8. DOI:10.36469/001C.26129. 7. Noor SM, Abuazzam F, Mathew R, Zhang Z, Abdipour A, Norouzi S. IgA nephropathy: a review of existing and emerging therapies. Frontiers in Nephrology 2023; 3: 1175088. 8. Floege J, Rauen T, Tang SCW. Current treatment of IgA nephropathy. Semin Immunopathol 2021; 43: 717–28. 9. Cheng J, Zhang W, Zhang XH, He Q, Tao XJ, Chen JH. ACEI/ARB therapy for IgA nephropathy: a meta analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int J Clin Pract 2009; 63: 880–8. 10. Reich HN, Troyanov S, Scholey JW, Cattran DC. Remission of proteinuria improves prognosis in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 18: 3177–83. 11. Rovin BH, Adler SG, Barratt J, et al. KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Glomerular Diseases. Kidney Int 2021; 100: S1–276. 12. Moriyama T, Karasawa K, Miyabe Y, et al. Long-Term Beneficial Effects of Tonsillectomy on Patients with Immunoglobulin A Nephropathy. Kidney360 2020; 1: 1270. 13. Kawabe M, Yamamoto I. Current Status and Perspectives on Recurrent IgA Nephropathy after Kidney Transplantation. Nephron 2023; : 1–5. 14. Moroni G, Belingheri M, Frontini G, Tamborini F, Messa P. Immunoglobulin A Nephropathy. Recurrence After Renal Transplantation. Front Immunol 2019; 10. DOI:10.3389/FIMMU.2019.01332. 15. Jiang SH, Kennard AL, Walters GD. Recurrent glomerulonephritis following renal transplantation and impact on graft survival. BMC Nephrol 2018; 19. DOI:10.1186/S12882-018-1135-7. 16. Zhao N, Hou P, Lv J, et al. The level of galactose-deficient IgA1 in the sera of patients with IgA nephropathy is associated with disease progression. Kidney Int 2012; 82: 790. 17. Berthoux F, Suzuki H, Mohey H, et al. Prognostic Value of Serum Biomarkers of Autoimmunity for Recurrence of IgA Nephropathy after Kidney Transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 28: 1943–50. 18. Clayton P, McDonald S, Chadban S. Steroids and recurrent IgA nephropathy after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 2011; 11: 1645–9. 19. Leeaphorn N, Garg N, Khankin E V., Cardarelli F, Pavlakis M. Recurrence of IgA nephropathy after kidney transplantation in steroid continuation versus early steroid-withdrawal regimens: a retrospective analysis of the UNOS/OPTN database. Transpl Int 2018; 31: 175–86. 20. Eckardt K-U, Kasiske BL, Zeier MG. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2009; 9 Suppl 3: S1–155. 21. Fellström BC, Barratt J, Cook H, et al. Targeted-release budesonide versus placebo in patients with IgA nephropathy (NEFIGAN): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. The Lancet 2017; 389: 2117–27. 22. Teoh JYC, Lau BSY, Far NY, et al. Attitudes, acceptance, and registration in relation to organ donation in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional study. Hong Kong Med J 2020; 26: 192–200.