Consultant in Cardiology

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia that is associated with substantial disability and mortality. For instance, individuals with AF are 5 times likely to have cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and 3 times likely to die from heart failure compared with people without AF1. While pharmacological treatment forms an essential component in managing AF, a healthy lifestyle consisting of a healthy high fibre diet with physical activity may reduce the risk of AF2. Moreover, public awareness on AF forms an important part of health education and prevention. Given the debilitating effects of AF, an early identification of the disease may facilitate early treatment, thereby, reduce the disease burden of the cardiovascular disease has on the local healthcare system. Therefore, in a recent sharing, Dr. Fu Chiu Lai discussed the urgent needs for therapeutics, health education, and prophylactic approach in patients with AF in the local clinical settings.

AF is characterised by high frequency excitation of the atrium that results in both dyssynchronous atrial contraction and irregularity of ventricular excitation3. The clinical consequences of AF are of paramount importance since AF increases the risk of embolic stroke (SE), heart failure, and premature mortality. Notably, AF has become a global epidemic affecting more than 33 million people worldwide and the incidences increases with age4. According to the report by the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS) 2021, the local prevalence of AF was approximately 1.8%5. On this note, Dr. Fu highlighted that the prevalence is probably underestimated since the estimate is dependent on the public awareness on the disease, public resources allocated to AF screening, and the accuracy of the screening tests. “The reported AF prevalence in the United States is 2-3 times higher than that in Hong Kong attributed by the comprehensive insurance and medical coverage available there,” Dr. Fu addressed.

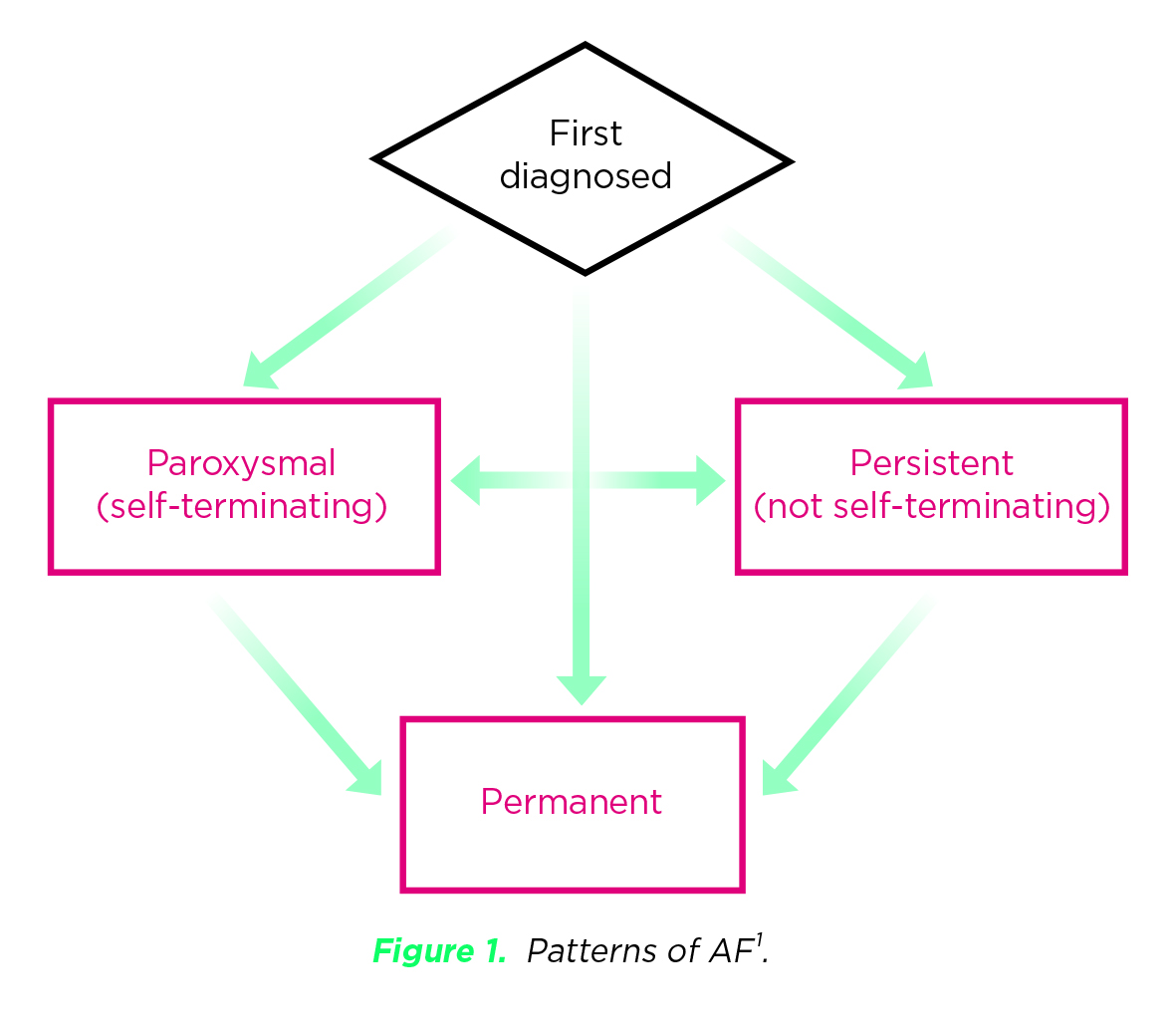

The impact of AF is highly variable with some individuals reported experiencing palpitations, chest discomfort or dizziness, whilst others remaining completely asymptomatic. A handful of patients may develop acute dyspnoea. Based on the duration and the type of arrhythmia, AF can be categorised in 3 major forms, namely paroxysmal, persistent, and permanent (Figure 1)1. Dr. Fu added that the irregular heartbeat can vary considerably among AF patients, “the irregular heartbeat can last for several seconds in some cases and for several minutes or even hours in others.” Provided that most patients with AF remain asymptomatic, identifying AF among patients can be clinically challenging.

Figure 1. Patterns of AF1.

AF patients are often identified when they develop AF-related complications, such as stroke or heart failure. For instance, studies have shown that atrial tachycardia is associated with the development of AF and subsequent stroke6. Apart from stroke, Dr. Fu suggested that heart failure is also a common AF-associated complication.

Urbanisation brings along not only economic benefits, but also causes a series of changes in an individual's dietary habits, lifestyles, and living environment. Many of these changes have been reported to contribute towards an increasing prevalence of various chronic diseases7. While rheumatic valvular disease (RVD) contributed to a significant portion of AF cases in Hong Kong two to three decades ago, Dr. Fu noted that the proportion of RVD-associated AF has since decreased while the urban-associated diseases have become more prevalent in the recent years.

“Diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, obesity, and sleep apnoea are considered as the urban-associated diseases which may predispose individuals to AF,” Dr. Fu stated. In addition, excessive alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking has been shown to increase the risk of developing AF8. She emphasised that a strong family history and genetic factor also increases the risk of AF further. In contrast to RVD-associated AF, the cases related to urban-associated factors are primarily nonvalvular diseases9.

In view of the association between urban-associated diseases and the risk of AF, Dr. Fu explained the importance of screening out those with AF, especially in high-risk populations. Aside from monitoring, it is essential to control the risk factors related to urban-associated diseases. Appropriate weight management and better control of sleep apnoea is required. Furthermore, the level of serum glucose and lipids as well as the blood pressure should be monitored at regular intervals. “Patients with early stages of diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, and hypertension may remain asymptomatic and there is a tendency for these diseases to occur in younger age groups,” according to Dr. Fu. Besides, having a balanced diet consisting of low saturated and trans fats, salt and sugars; and rich in fruit, vegetables and whole grains, as well as having regular exercise are highly recommended to reduce the risk of AF.

Once AF is diagnosed, a series of clinical assessments evaluating the risk of stroke should be conducted using the CHAD2DS2-VAS score and anticoagulants are commenced in high-risk groups. Warfarin is traditionally prescribed to reduce the risks of ischemic stroke/venous thromboembolism (IS/VTE). Even though the efficacy of warfarin in reducing the morbidity and mortality related to thromboembolism is well-established, the narrow therapeutic window and frequent blood monitoring of international normalised ratio (INR) is often required for dose-adjustments. Moreover, the therapeutic effects of warfarin can be affected by diet and through drug-drug interactions. Other drawbacks of warfarin include the increased risk of major and minor bleeding. Therefore, convincing patients to continue warfarin on a long-term basis often proves to be difficult in clinical practice10.

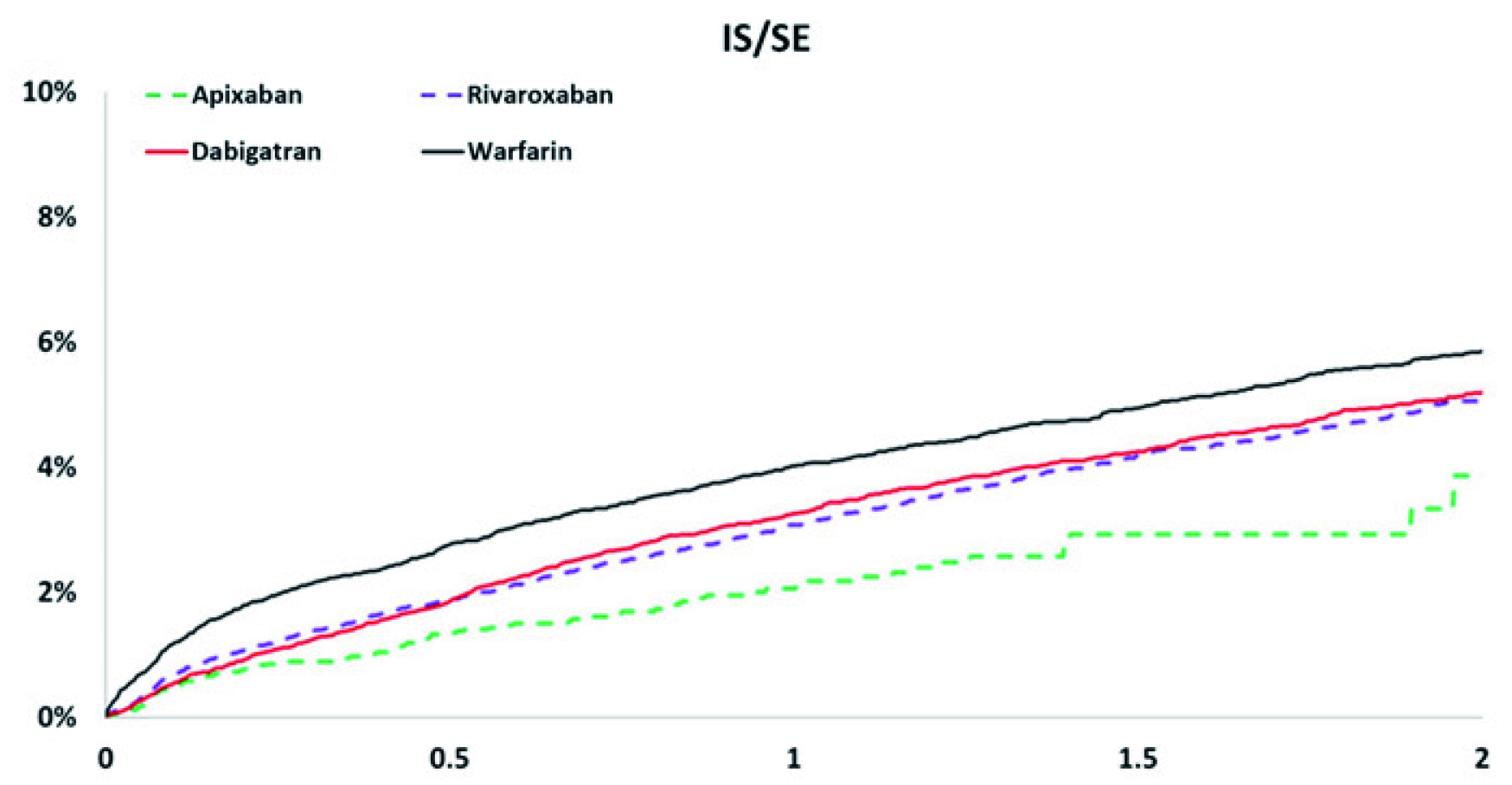

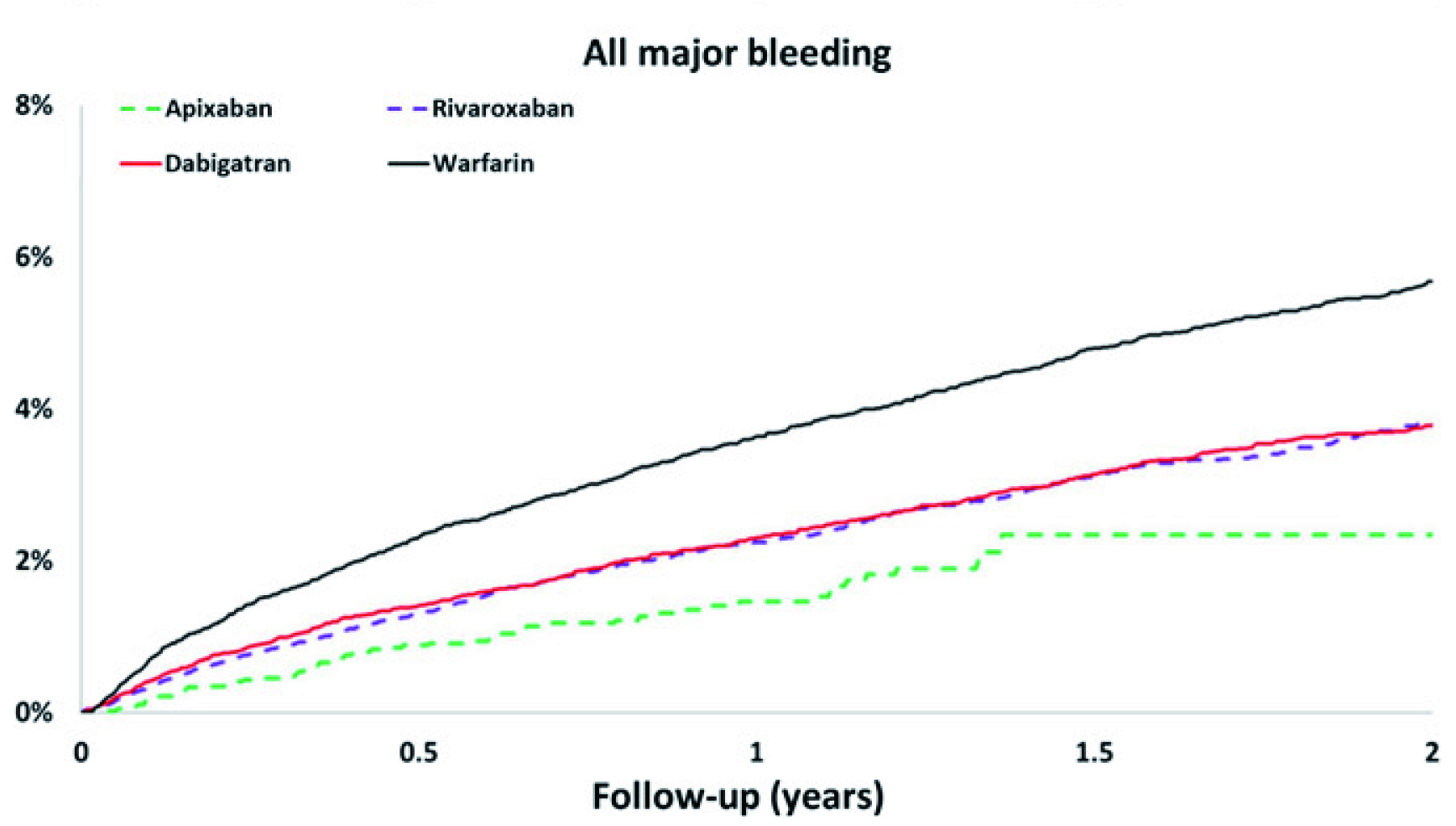

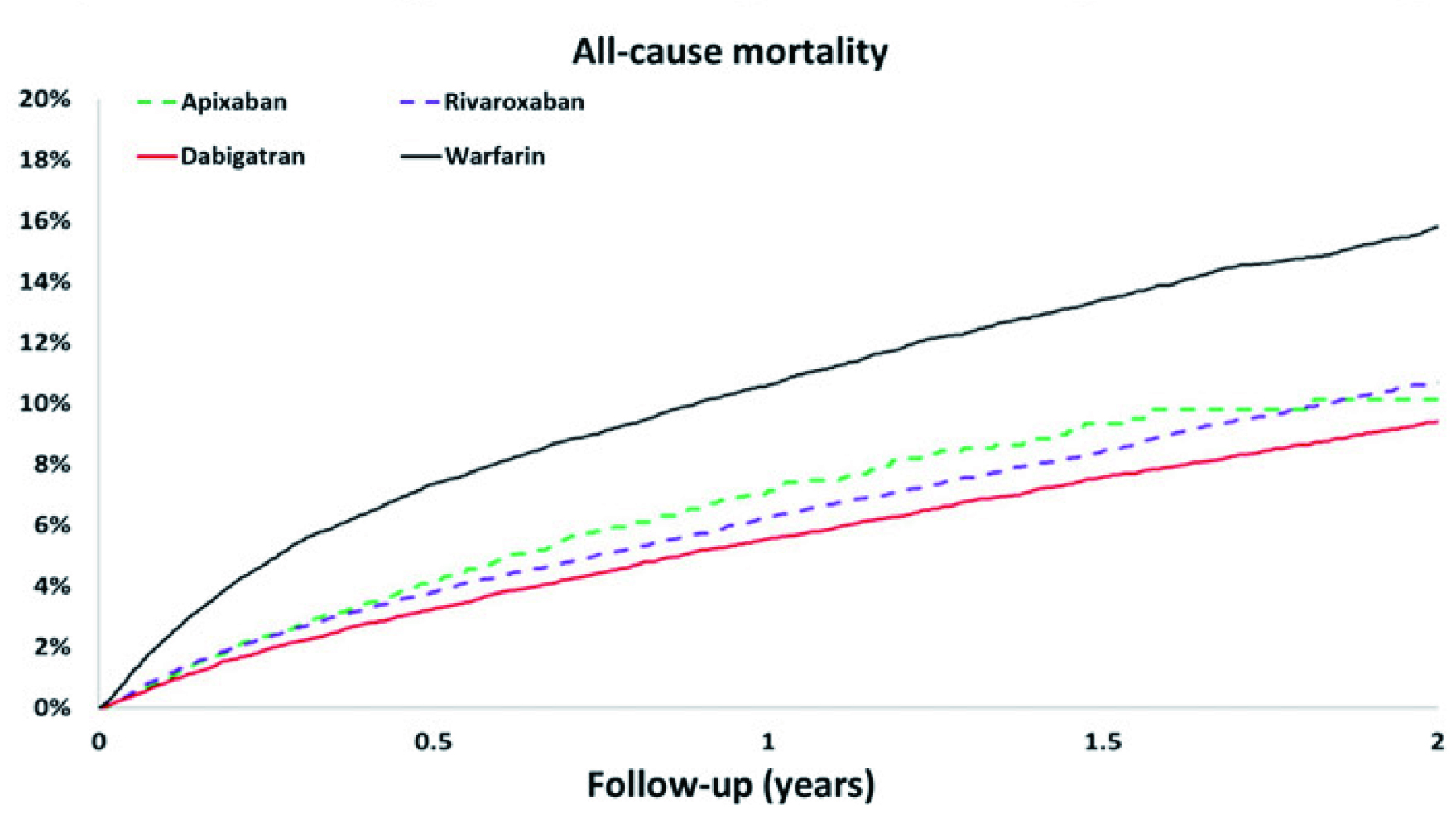

Thanks to the therapeutic advancement, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) are commercially available for patients with AF and a retrospective study conducted by Chan et al. (2018) demonstrated that the NOACs (apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban) were associated with lower risks of IS/SE, major bleeding, and mortality when compared to warfarin (Figure 2A-2C)11.

A

B

C

Figure 2. The cumulative incidence curves of A) IS/SE, B) all major bleeding, and C) all-cause mortality for patients with nonvalvular AF taking NOACs11.

Dr. Fu highlighted the pharmacological differences between the 4 NOACs currently available in the market. For instance, some NOACs are taken once-daily whilst others are twice-daily. She recommended monitoring the renal function and assessing the bleeding risk prior to commencing on NOACs. On a more serious note, Dr. Fu stressed that the choice of anticoagulation is often decided by the patients, while the duty of clinicians is to provide the treatment option, balancing between the benefit and harm.

Even though oral anticoagulation has shown to be effective in stroke prevention related to AF, studies have reported a substantial proportion of patients with AF having a CHA2DS2-VASc score of ≥2 were not anticoagulated. According to the IMPACT-AFib trial by Al-Khatib et al. (2020), which assessed the clinical data of 241,044 patients with AF, over one-third of AF patients with no apparent contraindications to an anticoagulant were not on treatment in during the last 12 months12.

Dr. Fu agreed that underutilisation of NOACs is common among local AF patients. She explained that although NOACs are easier to dose and administer compared to warfarin, the risk of internal bleeding remains the major adverse effect of NOACs hindering patients' compliance to the treatment. “When compared to Caucasians and Africans, Asians are at higher risk of bleeding when commenced on the NOAC treatment. Eventually, some may refuse to commence on NOACs due to the risk of bleeding,” Dr. Fu explained. She added that older adults are more susceptible to bleeding and a small percentage of patients may even suffer from haemorrhage bleeding after using NOACs. Therefore, it is paramount to explain to the patients the potential risks and costs associated with NOACs prior to commencing the treatment.

Clinically, there are diagnostic tools that can be used to evaluate the risk of internal bleeding among AF patients on NOACs. One of these tools includes the HAS-BLED score which is primarily used to estimate the bleeding risk in patients with AF13. Regarding the management of AF, Dr. Fu added that there are surgical options available for patients with AF and these include the surgical AF ablation, with promising efficacy in mitigating AF and avoiding the use of anticoagulation all together. “The decision of treatment protocol including the choice of medications and the need for pacemaker has to be considered on individual basis, and the paramount issue is to reduce the risk of stroke,” Dr. Fu advised.

As highlighted by Dr. Fu, the AF management involves a shared decision made between the physician and the patient. Particularly, the effectiveness of preventive measures, such as lifestyle risk modification, is largely determined by patients' willingness to change. Thus, patient education remains the core of AF management, empowering patients to engage in their treatment and management plan. Of note, health literacy is defined as the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services required to make appropriate health decisions14.

Dr. Fu commented that public in Hong Kong is knowledgeable and good at making sensible choices. Whereas, in the context of AF, improving people's understanding on the pathophysiology and treatment of AF would increase public awareness on AF and facilitate effective self-care in patients with AF. Given that AF can be asymptomatic initially, it would be difficult for patients and high-risk populations to appreciate the potential impacts of the disease. In this regard, Dr. Fu suggested that frontline healthcare professionals play a crucial role in providing accurate information on AF to patients and the public. “Participating in health talks and other media channels for public is an effective way for healthcare professionals to deliver health information,” Dr. Fu advised.

In addition, a recent qualitative study by Ferguson et al. (2022) indicated that application of multimedia, apps, case studies, and visual components may optimise learning. Moreover, the report suggested that continuity of care, including engagement of caregivers being important to help develop relationships, facilitate understanding, and create opportunities for timely targeted education15.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has proposed the criteria for a disease to be suitable for screening, which states that when the disease is an important health problem with an accepted treatment, there are facilities for diagnosis and treatment, there is a latent and symptomatic stage, the cost of finding is economically balanced with overall health16. While AF satisfies most of the criteria, Dr. Fu noted that the cost-effectiveness should be considered. “Screening for AF would be beneficial but compounded by the technical issues practically,” according to Dr. Fu. The first issue is the variable clinical manifestation of AF, which makes the AF diagnosis difficult. Therefore, a mass screening for AF is impractical.

Instead, Dr. Fu suggested an opportunistic screening for AF among high-risk populations and those newly diagnosed with AF by monitoring the change in beat-to-beat pattern during a specific interval using implanted loop recorders (ILR). She highlighted that the procedures for ILR are simple, and the battery life lasts between 3 to 5 years. The ILR is generally implanted subcutaneously and can generate accurate and continuous data on cardiac rhythms for physicians, allowing them to make an accurate diagnosis. Moreover, Dr. Fu emphasised that monitoring cardiac rhythm is essential since the clinical data would reflect whether the risk factors were effectively controlled and provide an insight on their condition, enabling treatment optimisation.

Apart from the use of ILR, a local territory-wide community-based AF screening programme carried out by Chan and Choy (2016) investigated the feasibility of community screening using smartphone-based wireless single-lead ECG (SL-ECG). The study recruited 13,122 residents from Hong Kong. The prevalence rate of AF detected by the SL-ECG was 1.8%17. The study demonstrated the potential use of innovative technologies in generating epidemiological data of AF in local settings.

Dr. Fu stated that the management of AF in the past was very complicated and limited by the availability of the diagnostic tools. Notably, the treatment outcomes remained unsatisfactory. However, the development of pharmaceuticals and surgical treatments have significantly improved the outcomes of AF. Nonetheless, early diagnosis of AF remains a challenge, as patients with AF are only diagnosed when admitted to hospital for acute cardiac decompensation or stroke. This highlights the importance of improving the public awareness on AF, particularly among the high-risk groups. At the same time, improving health literacy remains the first step of disease prevention. Dr. Fu advised that the local media and government organisations have attempted to educate the target populations for AF. Nonetheless, to reach a wider audience, the use of digital platforms is required since this would facilitate effective delivery of health information to those in need. In addition, over the next few years, technical advancement is expected to take a further leap with the help of artificial intelligence (AI). In conclusion, Dr. Fu expressed her concerns regarding AF and complications related to the condition. She advocated more research into this area, which would help us understand more on AF, and develop novel therapies which may one day reduce the prevalence of the disease and improve overall-survival outcomes related to cardiovascular diseases attributed by AF.

References

1. Department of Health. Non-Communicable Diseases Watch Atrial Fibrillation. 2016. 2. Shamloo et al. Rom J Intern Med 2019; 57: 99–109. 3. Staerk et al. Circ Res 2017; 120: 1501 4. Calvo et al. Pharmacol Rev 2018; 70: 505–25. 5. Chan et al. J Arrhythm 2022; 38: 31–49. 6. Eyituoyo et al. Cureus 2020; 12. DOI:10.7759/CUREUS.9420. 7. Luo et al. Front Public Health 2022; 10: 1042413. 8. Body et al. Eur Heart J 2017; 38. DOI:10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHX502.1190. 9. Wańkowicz et al. Arch Med Sci 2019; 15: 1217. 10. Kneeland et al. Patient Prefer Adherence 2010; 4: 51. 11. Chan et al. J Am Heart Assoc 2018; 7. DOI:10.1161/JAHA.117.008150. 12. Al-Khatib et al. Am Heart J 2020; 229: 110–7. 13. Zhu et al. Clin Cardiol 2015; 38: 555–61. 14. Boonstra et al. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2021; 36: 1207–21. 15. Ferguson et al. J Am Heart Assoc 2022; 11. DOI:10.1161/JAHA.122.025293. 16. World Health Organization. Principles and practice of screening for disease. 1968. 17. Chan et al. Heart 2017; 103: 24–31.